Psychotherapy Knowledge Translation and Interpersonal Psychotherapy: Using Best-Education Practices to Transform Mental Health Care in Canada and Ethiopia

Abstract

Psychotherapies, such as Interpersonal Psychotherapy (IPT), that have proven effective for treating mental disorders mostly lie dormant in consensus-treatment guidelines. Broadly disseminating these psychotherapies by training trainers and front-line health workers could close the gap between mental health needs and access to care. Research in continuing medical education and knowledge translation can inform the design of educational interventions to build capacity for providing psychotherapy to those who need it. This paper summarizes psychotherapy training recommendations that: adapt treatments to cultural and health organizational contexts; consider implementation barriers, including opportunity costs and mental health stigma; and engage local opinion leaders to use longitudinal, interactive, case-based teaching with reflection, skills-coaching, simulations, auditing and feedback. Community-based training projects in Northern Ontario, Canada and Ethiopia illustrate how best-education practices can be implemented to disseminate evidence-supported psychotherapies, such as IPT, to expand the therapeutic repertoire of health care workers and improve their patients’ clinical outcomes.

Introduction

The burden of common mental disorders (CMD) such as mood disorders, stress-related, and somatoform disorders takes a significant toll on individuals and society, with depressive disorder attributing to 42.5% of all years-lived-with-disability (Whiteford et al., 2013). Psychotherapy is an effective treatment for CMD and is recommended in consensustreatment guidelines (American Psychiatric Association, 2006; Kennedy, Lam, Parikh, Patten, & Ravindran, 2009; National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence, 2011; World Health Organization, 2010b). However, empirically validated psychotherapies are not readily available worldwide to most people who have CMD, for a variety of reasons, but in part, because there are too few health professionals trained to provide psychotherapy (Weissman, 2013a, 2013b; Weissman et al., 2006). This is not just a problem for developing countries; in the 2012 Canadian Community Mental Health Survey (Sunderland & Findlay, 2013), one-third of those who endorsed a need for mental health care reported that this need was unmet. Furthermore, “counseling” (which includes psychotherapy) was the highest ranked mental health need and the one least likely to be met.

Calls for global action to reduce the gap between the need for, and access to, effective mental health care (Prince et al., 2007) have led to changes in national mental health strategies (Federal Democratic Republic of Ethiopia Ministry of Health, 2012; Mental Health Commission of Canada, 2009) and funding initiatives (Grand Challenges Canada, 2013; National Institutes for Health, 2013). In an exciting global movement now underway, numerous groups are demonstrating the feasibility and clinical effectiveness of psychotherapies delivered by trained professional and lay health workers in underserved communities (Bass et al., 2006; Bolton et al., 2007; Bolton et al., 2003; Dua et al., 2011; Patel, Chowdhary, Rahman, & Verdeli, 2011; Patel et al., 2011; Ravitz et al., 2013; Verdeli et al., 2003). Expanding resources available for people with CMD requires training of front-line health providers to expand their clinical scope of practice to include treating mental health problems and using evidence-supported psychotherapy. Efforts to do so have been encouraging. In a Cochrane review of 38 studies that compared usual health care services with mental health care delivered by non-specialist health workers in low- and middle-income countries, it indicated that treatment delivered by non-specialists improves depression, post-traumatic stress disorder, dementia, and alcohol-use disorders (van Ginneken et al., 2013). Most of the studies in this review included some form of psychosocial intervention (e.g., psychoeducation), with sixteen studies using specific psychotherapies (e.g. cognitive-behavior therapy (CBT), interpersonal psychotherapy (IPT), motivational interviewing) on their own or within a stepped, collaborative-care model. Scaling up mental health services is needed to reduce the global health disparities of “the bottom billion” within a framework of sustainable capacity-building mental health care training packages and quality-improvement practices (Belkin et al., 2011). Although curricular guidelines and cultural adaptations exist for these types of frameworks, little attention has been paid to evidence-based training processes to disseminate evidence-supported psychotherapies, which is the focus of this paper. This paper summarizes psychotherapy training recommendations that: adapt treatments to cultural and health organizational contexts; consider implementation barriers, including opportunity costs and mental health stigma; and engage local opinion leaders to use longitudinal, interactive, case-based teaching with reflection, skills-coaching, simulations, auditing and feedback. Community-based training projects in Northern Ontario, Canada and Ethiopia illustrate how best-education practices can be implemented to disseminate evidence-supported psychotherapies to expand the therapeutic repertoire of health care workers and improve their patients’ clinical outcomes. We use IPT (Weissman, Markowitz, & Klerman, 2007) to exemplify training recommendations derived from this review of knowledge translation (KT), continuing medical education (CME) and dissemination research.

Knowledge Translation and Continuing Medical Education Research

This paper’s pedagogic recommendations stem from high quality evidence that includes systematic Cochrane Reviews1 in KT and CME research (Baker et al., 2010; D. Davis & Davis, 2010; N. Davis, Davis, & Bloch, 2008; Flodgren et al., 2011; Forsetlund et al., 2009; Ivers et al., 2012; Kitto, Bell, Goldman, et al., 2013; Kitto, Bell, Peller, et al., 2013; Kitto, Nordquist, Peller, Grant, & Reeves, 2013; Sargeant et al., 2011).

Knowledge translation involves the dissemination of evidence-supported treatment guidelines to improve health care and change health provider practice behaviours to implement guidelines “from bench to bedside.” This involves adapting knowledge and dissemination processes to local contexts, addressing barriers to uptake, and evaluating outcomes (Graham & Tetroe, 2007; Straus, Tetroe, & Graham, 2009). Psychotherapy KT strategies can be applied at differing levels of intensity and scale. High-intensity training strategies require intensive longitudinal clinical supervision with the goal to achieve the highest levels of fidelity to guidelines. Scaling up strategies usually involve a lower intensity training of large numbers of health providers, with the goal of broad dissemination (Patel, Goel, & Desai, 2009).

Continuing medical education involves ongoing educational activities of health professionals, often in the form of didactic workshops, with learning objectives related to knowledge, skills, and professional performance to enhance patient care and clinical competence (Sargeant, et al., 2011). Davis and Davis (2010) describe education as an intervention with a continuum of learning outcomes, from the inoculation of awareness that comes from didactic methods, to sustained practice changes that can arise from longitudinal interactive methods.

Research in KT and CME over the past two decades has been assessed in systematic Cochrane Reviews of teaching processes, formats, and materials that are most likely to change health practitioner behaviour and improve patient outcomes (Table 1). In this paper, we first review the KT and CME research to formulate recommendations for the content and processes of psychotherapy training. Then, looking to the literature on psychotherapy supervision, a frontier where there is less evidence, we review expert consensus recommendations. Finally, we discuss barriers to and facilitators of the dissemination of evidence-supported psychotherapies with illustrative examples from the CE-to-Go Project in Canada (Ravitz, Cooke, et al., 2013) and the Biaber Project to scale up IPT in Ethiopia (Pain, Wondimagegn et al., 2013). As a language convention, we will generally use the term “teachers” to describe trainers, clinical supervisors, or mentors, and “learners” to describe trainees, students, or mentees.

| Teaching Elements | Methods (S = studies; HC = healthcentres; HP = health professionals) | Recommendations and Results | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Identify Barriers | S = 26 RCTs; HP = 2189 | Tailored interventions to overcome identified barriers (e.g. administrative constraints, patient expectations, clinical uncertainty) improve professional performance such as adherence to guideline recommendations. (OR = 1.52; 95% CI, 1.27 − 1.82; P&<0.001) | Baker et al. 2010#◊ |

| Work-based Learning Culture | S = 24 studies | The Promoting Action on Research Implementation in Health Services model (PARIHS) can be used to prospectively design/comprehensively evaluate implementation activities | Helfrich et al. 2010 |

| S = 10 studies | PARIHS framework’s organizational, contextual factors have a significant relationship with clinical guideline implementation: The context is a potent mediator of implementation of evidence into practice. Contextual factors that promote successful implementation are related to: (i) culture (of learning); (ii) transformational leadership; and (iii) evaluation with (iv) multifaceted support; protected time for and provision of education. | Meijers et al. 2006* | |

| Audit & Feedback | S = 140 RCTs; HP = 4363 | Feedback has a small positive effect when baseline performance is low, the source is a supervisor/colleague, provided > once, given in both verbal and written formats, includes targets and action plans. | Ivers et al. 2012#* |

| Opinion-leaders as faculty | S = 18 RCTs; HC = 614 | Use of opinion leaders has a small positive effect on compliance and can successfully promote evidence-based practices. | Flodgren et al. 2011#* |

| Use of Reflection | S = 29; HP = 2595 | Reflective thinking in students appears to be associated with approaches to learning; specifically, reflective thinking at the deeper levels is associated with deep approaches to learning and meaning-making. | Mann et al. 2009* |

| Workshop Format (didactic v. interactive) | S = 81 RCTs; HP = 11,000 | Educational meetings using mixed didactic and interactive formats have a small positive effect on professional practice and health care outcomes for the patient. | Forsetlund et al. 2009#* |

| Practice-reminders/Print materials | S = 45 studies; HP = 294,937 | Printed materials have a small beneficial effect on professional practice outcomes. | Giguère et al. 2012#* |

| Supervision | S = 24; HP = 170 | Enhanced clinical supervision of trainees associated with improved patient- and education-related outcomes | Farnan et al. 2012* |

| S = 42 studies | Effective educational and clinical supervision is best offered in context, in a structured format, with constructive feedback. Helpful supervisory behaviours include providing direct guidance on clinical work, engaging in joint problem solving, offering feedback and reassurance as well as being a role model. | Kilminister et al., 2007 |

Table 1 META-ANALYSES AND SYSTEMATIC REVIEWS OF KNOWLEDGE TRANSLATION, CONTINUING MEDICAL EDUCATION AND CLINICAL SUPERVISION STUDIES

Identify Barriers and Facilitators of Dissemination

To plan educational interventions for knowledge transfer of clinical guidelines, in this case of psychotherapies, the first step is to identify barriers to dissemination as they relate to learning, health practice behaviors, and implementation. Baker et al. (2010) systematically reviewed 26 studies and concluded that professional practice is more likely to change when barriers are identified and dissemination interventions are tailored to target these barriers (95% CI, 1.27 to 1.82, P < 0.001). Attitudinal, psychological, practical, structural, or cultural barriers can occur at the levels of individual learners, teachers, patients, organizations, and communities. Furthermore, an individual’s attitudinal barriers to learning or practicing psychotherapy can interact with the health service context, organization or cultural factors to facilitate, or impede the processes of implementation. Assumptions may mislead teachers when working across cultures, leading them to overlook differences in acceptability, feasibility, or impact. For example, high service demands at the clinic level may make it impossible for health providers to devote the time prescribed (e.g., 30 to 60 minutes per session and up to 16 sessions per patient) in standard time-limited models of psychotherapy. Furthermore, changing training and clinical practice may require seeking and receiving permissions at the clinic and higher systems levels (e.g., from managers, national and local health planners and co-ordinators).

An 18-year (1990-2008) systematic review of training service providers in evidence-supported treatments for at-risk and clinical populations highlighted that each health worker is “nested within a context” (Beidas & Kendall, 2010, p. 20) and that this, along with organizational, health worker and patient variables, interacts with training to affect practice behaviour changes, uptake, and implementation. Health services research to promote guideline implementation describes workplace learning-culture ideals with transformative leaders. It also describes an empowering approach to teaching, learning and management facilitated by monitoring, feedback, and evaluation using adult learning approaches with critical reflection (Helfrich et al., 2010; Kitson et al., 2008; Meijers et al., 2006; Rycroft-Malone, 2004).

A discussion of barriers to implementing mental health care is not complete without considering the powerful force of mental health stigma. Stigma interferes at multiple levels with seeking, providing, and receiving mental health care. Mental health literacy teaching to reduce stigmatizing attitudes in health care providers is an important precondition for scaling up mental health care treatment because providers’ stigma is often high (Sartorius, 2002, 2007; Stuart, 2012; Thornicroft, Rose, & Kassam, 2007); however, teaching against stigma, which equates a mental illness with a medical illness and intends to prevent blame, may unsettle rather than reassure patients in a low-income country where medical illnesses are often not associated with effective treatment. Furthermore, it is important to recognize local explanatory models of illness can differ significantly between cultures. In Ethiopia, for example, severe and persistent mental illnesses are understood as being caused by spiritual inflictions and possession states and are stigmatized (Alem, Desta, & Araya, 1995; Alem, Jacobsson, & Hanlon, 2008; Alem, Jacobsson, Kebede, & Kullgren, 1999). Because explanatory models influence help-seeking, most Ethiopians with severe mental illnesses go to nonmedical, spiritual or traditional healers (Mogga et al., 2006; Mulatu, 1999). In contrast, Ethiopians may view individuals with CMD as stressed by life and symptomatic, but not mentally ill (Hanlon, Whitley, Wondimagegn, Alem, & Prince, 2009). As depression, anxiety, and somatoform disorders are increasingly recognized as mental disorders in developing countries, there is a risk that stigma will also increase. This risk is arguably balanced by the benefits of decreasing suffering, reducing suicides, and of patients’ functioning (Abdullahi Bekry, 1999; Alem, Kebede, Jacobsson, & Kullgren, 1999). Programs can mitigate mental health stigma by offering culturally adapted treatment, which include respectful engagement of patients, families, and health providers. Thus, the goals of psycho-education and treatment engagement require assessment with sensitivity to cultural and contextual understandings of the meanings and impacts of illness.

In the specific case of training learners to use psychotherapy in differing cultural settings, teachers must appreciate how potential users and providers of mental health care understand, describe, and address mental health. They can do so through ethnographic, qualitative research before and during dissemination of psychosocial treatments to iteratively identify needed adaptations that are responsive, engaging, acceptable, feasible, and effective. We recommend using cultural formulation questions about meanings of illness, expectations, preferences, and pathways to care to create space for reflection and to promote knowledge exchange about cultural or spiritual practices of coping with mental health problems (American Psychiatric Association, 2013; Kleinman, 1977). This can help identify barriers to treatment engagement and tailor clinical models of practice. Culturally adapted treatments should follow a “systematic modification of an evidence-based treatment (EBT) or intervention protocol to consider language, culture, and context in such a way that it is compatible with the client’s cultural patterns, meanings, and values” (Smith, Rodriguez, & Bernal, 2011). Smith’s 2011 meta-analysis of 65 psychotherapy studies, which were conducted with 8620 patients of mostly Asian, Hispanic/Latino, and African American backgrounds, revealed that those receiving culturally adapted treatments experienced superior outcomes compared to patients in standard treatment control groups (d = 0.46). In a meta-analysis of psychotherapy for patients with major depression, Cuijpers et al. found improved outcomes when the psychotherapy model was adapted to respond to individual patient or patient population differences, including cultural adaptations and studies conducted in low income countries (Cuijpers, van Straten, Andersson, & van Oppen, 2008).

Learning Objectives

Learning objectives and curricular content for training should respond to learners’ needs and identified gaps in patient or population health needs and health care. However, learners need motivation to change their practice behaviours. Learners’ perceived learning needs are important, but learning needs should also be identified objectively because learners may be unaware of deficits or may misperceive their needs (e.g., overestimating competence). Learners are most likely to be motivated if they are aware of gaps between clinical practice guidelines and their own practice behaviours, and if they appreciate the relevance of changing their practice (e.g., better clinical outcomes). There are various ways to identify learning needs, including patient feedback, critical incidents, and consultations with key informants representing the differing kinds of learners that educational interventions intend to target. Health-systems research informs learning needs by highlighting gaps between public health needs and care, for example the World Health Organization’s call for action (2010), the Mental Health Gap Action Programme (mhGAP) initiative, and the report of the Canadian Commission on Mental Health (Mental Health Commission of Canada, 2012; World Health Organization, 2001). At an individual level, surveying health workers can also identify learning needs. Although self-assessed learning needs have limited ability to identify objectively determined gaps, they serve to ascertain individual health professional learner’s interests.

Learning objectives serve to define the focus of educational interventions, and to improve their effectiveness, relevance, and acceptability. Beyond simply raising awareness, learning objectives should specifically describe what learners can achieve as a result of participating in the learning activity, e.g., knowing something that could be tested or performing a clinical skill.

As individual health workers become more competent and encounter various clinical challenges over time, learning needs will change. Teaching should respond to the dynamics and issues that emerge from practice-based experiences through longitudinal clinical support and supervision (Graham & Tetroe, 2007; Straus, et al., 2009). Feedback from health learners and patients should be gathered systematically using clinical tools (e.g. check-lists and validated symptom measures) to track clinical outcomes, practitioner behaviors, and guide practice-based learning (Belkin, et al., 2011). Ivers and colleagues (2012) describe a process of audit and feedback as a “summary of the clinical performance of health care provider(s) over a specified period of time,” (p. 5) where feedback may come in written, electronic or verbal format. Ivers’ Cochrane review of 140 randomized controlled trials that used feedback with practice audits, covering over 2000 health provider groups and individuals, found modest improved adherence to desired health practice behaviours (Absolute risk difference of 4.3%; Interquartile range of 0.5% to 16%). The review specified that feedback with precise goals and an action plan is more effective when given more than once by a supervisor, mentor or respected colleague, in both verbal and written formats, especially when baseline health learner performance is low.

Who Should Teach?

Compelling research has explored the question of who can best teach and champion the dissemination of clinical guidelines. Opinion leaders, defined as local professional peers who have earned respect, trust, and credibility–the kind of clinicians with whom a health worker might informally consult in the workplace or community (and who are not necessarily leading subspecialty experts)–are effective teachers and agents of behavioral change. Because of their influence, opinion leaders can effectively persuade health care providers to change practices. A Cochrane review found an overall 12% absolute increase in compliance in the intervention groups of 18 heterogeneous randomized controlled trials in 296 hospitals and 318 primary care health centres evaluating the effectiveness of using opinion leaders to disseminate and implement evidence-based medicine (Flodgren, et al., 2011).

Reflection

Training in psychotherapy and counselling, beyond teaching model-specific techniques, confers professional attitudes and values related to self-reflection (Charon, 2001), patient-centered care, and skills that are related to using empathy and maintaining a therapeutic alliance (Horvath, Del Re, Fluckiger, & Symonds, 2011). Reflective capacity is important for all health care practitioners (Eva et al., 2012; Sargeant, Mann, van der Vleuten, & Metsemakers, 2009), not just psychotherapists. Reflection has been defined as “… a metacognitive process that occurs before, during and after situations with the purpose of developing greater understanding of both the self and the situation so that future encounters with the situation are informed from previous encounters” (Sandars, 2009). In a systematic review of 29 studies (with >2500 health providers) on using reflection in health teaching, Mann et al. (2009) highlight the importance for learners to develop capacities for reflective clinical reasoning and responsiveness (Mann, Gordon, & MacLeod, 2009). A grounded theory qualitative study with 28 family physicians concluded that reflection is useful in assessing and integrating feedback, especially negative feedback (Sargeant, et al., 2009). Reflective capacity has been described as essential to the humanizing of health care (Eva, et al., 2012; Sargeant, et al., 2009) and is a core skill of psychotherapy and counselling.

For a guided reflective process to occur in the context of psychotherapy training the learning climate must feel psychologically safe and the teacher or mentor must deliver feedback from a position of beneficence. Awareness of a trainee’s vulnerability or fears of losing face, appearing incompetent, or losing confidence can sensitize teachers to the importance of giving constructive feedback in a non-maleficent manner (Eva, et al., 2012).

Empathy, and the Therapeutic and Learning Alliances

Teaching psychotherapy is helped when teachers model important elements of empathy and therapeutic alliance by demonstrating empathy toward learners and attending to the learning alliance. This parallel process makes the process of teaching congruent with its content. Meta-analyses have demonstrated that therapeutic alliance and empathy, two factors common to all therapy models, predict positive outcomes more than model-specific factors (Norcross & Lambert, 2011). Horvath and Del Re’s (2011) meta-analysis of more than 200 studies with greater than 14,000 treatments found a small but positive relationship between the quality of the therapeutic alliance and outcome (r = 0.275, p < 0.0001) (Horvath, et al., 2011). Elliott et al.’s meta-analysis of 57 studies with >3500 patients demonstrated empathy as a modest positive predictor of psychotherapy outcome (r = 0.31, p < 0.001) (Elliott, Bohart, Watson, & Greenberg, 2011). Thus, teaching about the therapeutic alliance and empathy is recommended in all psychotherapy training. Even subtle expressions of therapist hostility or negative judgment can contribute to poor psychotherapeutic outcomes because they adversely affect the therapeutic alliance (Norcross & Lambert, 2011; Von Der Lippe, Monsen, Ronnestad, & Eilertsen, 2008). The same may apply to learning outcomes if teachers give feedback that is subtly hostile or overly focused on negative judgments, which adversely affects the learning alliance.

Which Teaching Formats Work Best?

Health professionals learn best through interaction with peer-colleagues using multimodal methods, including simulations (Forsetlund, et al., 2009). Effective active learning methods include practicing on nonpatients, role playing with observation and feedback, and participating in reflective case-based discussions. These kinds of learning activities can augment the acquisition of knowledge and clinical skills, while increasing attention to and retention of content.

Reading (e.g., of psychotherapy manuals) or attending workshops alone does not result in skill acquisition, adoption of psychosocial treatments, or improved patient outcomes. A review of 55 community-based mental health provider training studies evaluated various teaching formats (Herschell, Kolko, Baumann, & Davis, 2010). Specifically, they examined the effects of treatment manuals, self-directed training, workshops, workshops supplemented with follow-up supervision, pyramid training (train-the-trainers), and multi-modal training, e.g., a treatment manual, multiple days of intensive workshop training, observation, supervisor training, booster, and supervised training of multiple cases. There were few studies of training-of-trainers, a process that has potential for time and cost efficiency. The authors concluded that multi-modal teaching with consultation, supervision and feedback had the strongest evidence for improving health learners’ skills and knowledge uptake.

Combining print materials (“practice reminders”) with interactive lessons has a moderately positive impact on professional practice. Giguère and colleague’s (2012) Cochrane Review of 45 studies assessing over 290,000 participants concludes that tailored practice reminders can over-come some barriers to change and can enhance professional practice (absolute risk difference = 0.02). Print materials can include published or printed recommendations for clinical care in the form of clinical practice guidelines, monographs, and publications in peer-reviewed journals (Giguère et al., 2013).

Psychotherapy Supervision

Supervision, a form of longitudinal practice-based teaching in small groups or with individuals, helps learners apply principles and skills in clinical practice settings. It typically follows didactic foundational learning. Alternatively, groups training lay counsellors to provide psychotherapy in low income countries’ mental health care have used a traditional apprenticeship model with staged learning-by-doing, longitudinal supervision, use of print materials, and feedback (Chatterjee et al., 2008; Murray et al., 2011; Patel, Weiss, et al., 2011; Verdeli, et al., 2003). This incorporates a number of the above mentioned recommendations.

Ensuring learner and patient psychological safety in the clinical care context involves monitoring progress, giving guidance to the learner on clinical work, modeling, and engaging collaboratively in reflective clinical reasoning to understand patient problems and to generate ideas for approaches to respond and help, with constructive performance feedback. Feedback in psychotherapy supervision should provide learners with information to improve their clinical effectiveness and their patients’ outcomes.Kilminster et al.’s review of clinical supervision (2007) offers a cautionary list of ineffective supervisory behaviours which may interfere with a psychological safe learning environment including “low empathy; failure to offer support; failure to follow supervisees’ concerns; not teaching; being indirect and intolerant and emphasizing evaluation and negative aspects” (Kilminster, Cottrell, Grant, & Jolly, 2007, p. 7.).

A systematic review of 24 controlled studies evaluating clinical supervision and outcomes in patient care or residency education found positive associations; however, the studies had varied methodological limitations (Farnan et al., 2012). Weerasekera did a 12-year exploratory review of 42 studies of psychotherapy supervision in psychiatric training in the United States and Canada to examine content, process, and assessment of psychotherapy competence (Weerasekera, 2013). She concludes that alliance building provides an essential foundation to teaching all psychotherapies and that modeling, learner skill rehearsal (including role-plays), and observation-based feedback have the best evidence as teaching processes that enhance psychotherapy competence. Weerasekera recommends assessing the effectiveness of training using validated measures of learner adherence and competence as well patient outcomes. For example, in Western settings, she suggests measuring learner’s empathic ability (Simmons, Roberge, Kendrick, & Richards, 1995; Truax, 1972), the therapeutic alliance (Hatcher & Gillaspy, 2006), IPT competence (Hollon et al., 1988) or CBT competence (Vallis, Shaw, & Dobson, 1986). Patient outcomes can be tracked with symptom measures (e.g. Beck Depression Inventory, Kessler Psychological Distress Scale, Self-Report Questionnaire) (Beck, Ward, Mendelson, Mock, & Erbaugh, 1961; Harding et al., 1983; Kessler et al., 2003) and functional measures, (see World Health Organization Disability Assessment Schedule 2.0, 2010a). Psychotherapy supervision with feedback and/or coaching, especially when coupled with observation beyond narrative reports by learners, can improve proficiency and competence (Miller, Yahne, Moyers, Martinez, & Pirritano, 2004; Sholomskas et al., 2005). When direct observation (or observation by reviewing video or audiotaped sessions) is not possible, a proxy of auditing through chart or behaviour check-list review may improve treatment adherence and guide clinical teaching.

What does good clinical supervision look like? Teachers should begin clinical supervision by asking trainees to self-assess process and outcome: “What do you think went well? What did you struggle with? How are your patients doing?” In psychotherapy supervision, teachers need to wonder with the learner about how the patient is experiencing treatment and if suffering or symptoms are diminishing (Lambert & Shimokawa, 2011). The teacher elicits the learner’s description of the patient encounters, paying attention to the central and emotionally charged concerns. To foster a clinically reflective capacity, teachers ask learners about their thoughts regarding these concerns or problems. Teachers need to acknowledge their learners’ concerns and together brainstorm ways to understand and address issues (e.g., about acuity, lack of progress, safety, or the alliance). Teachers model retrospective ‘reflecting-on-action’ to help learners ‘reflect-in-action’ during future clinical sessions with their patients (Schön, 1983). Difficult dilemmas that evoke embarrassment or feelings of vulnerability merit nonjudgmental discussion and empathic framing as learning opportunities. Sometimes the learner needs only to understand the patient differently, or how to address contextual challenges. Other times, supervisors may recommend specific clinical practice changes. Training must also include teaching about necessary fiduciary duties, confidentiality, professional behaviours and relationships boundaries in psychotherapies - where patients may disclose very personal information and become distressed during sessions. In the latter case, providing the rationale will help to motivate clinically-reasoned therapeutic behavior changes. Doing a role-play/rehearsal with the learner to practice the desired-for clinical behaviours can help to facilitate the acquisition through experiential learning of new skills. In addition, reviewing a videotaped simulation of therapeutic techniques in which the desired-for clinical practices are modeled can be helpfully consolidating.

Psychotherapy Knowledge Translation: The “CE to GO” and “Biaber” Projects

The “CE (Continuing Education) to Go” Project involved front-line health workers in community-based mental health clinics in underserviced rural communities of northern Ontario, Canada. Following an assessment of learning needs, the project team developed a menu of education courses in evidence-supported psychotherapies on core techniques of CBT (Beck, Rush, Shaw, & Emery, 1979; Fefergrad & Richter, 2013; Fefergrad & Zaretsky, 2013), IPT (Klerman, Weissman, Rounsaville, & Chevron, 1984; Ravitz, Watson, & Grigoriadis, 2013; Weissman, et al., 2007), Motivational Interviewing (Cooper & Skinner, 2013; Miller, 1983; Miller & Rollnick, 1991), and Dialectical Behavior Therapy (Linehan, 1993a, 1993b; McMain & Wiebe, 2013). Each course included: a videotaped lecture-demonstration; four case-based interactive lesson plans that use multi-modal teaching methods and videotaped, captioned simulations; and print materials with clinical practice pocket-card reminders (Ravitz & Maunder, 2013). Two of the courses offered in seven clinics, received a mixed methods evaluation from 93 mid-level nonmedical front-line mental health workers. Self-reported knowledge, morale, confidence in being able to provide psychotherapy, and comfort in working with difficult clients significantly improved (Ravitz, Cooke, et al., 2013).

The “Biaber Project” to scale up IPT in Ethiopia (Pain, Wondimagegn, et al., 2013) is incorporating multi-site tiered training-of-trainers, first by psychiatrists, then by mid-level mental health specialists (such as psychiatric nurses and clinical psychologists), ultimately training front-line primary health workers (e.g., family doctors, nurses and medical officers). “Der biaber anbessa yaser” is an Amharic saying that translates into English as, “together we will weave a spider web to tie a lion.” This expression evokes the intentions of “The Biaber Project,” to tame the lion of untreated mental illness. The goals of this project are to harmonize and strengthen the mental health system, integrating mental health care within a general health system that will include shared care with the traditional healers, to whom most Ethiopians first go in their pathways to care. Collaborators on the Biaber Project, through the Toronto Addis Ababa Psychiatry Program (TAAPP), have worked together for 10 years to co-train 80% of Ethiopia’s psychiatrists, who now number >50 (Alem, Pain, Araya, & Hodges, 2010). A mere decade ago, Ethiopia had only 11 psychiatrists, all foreign trained, for a population of more than 80,000,000. This collaborative project has enabled the opening of five psychiatrist-led psychiatric departments within university-affiliated teaching hospitals outside the capital city of Addis Ababa, and it forms the basis from which the Biaber Project has emerged. In order to integrate mental health within the general health system, linked networks of mental health treatment and training are needed. In primary care settings, evidence-supported psychosocial interventions that attend to the social contexts of illness, such as IPT, can be applied at modest cost once health care providers are adequately trained. Although pharmacotherapy exists as a treatment option, not all patients are agreeable to take medication, and furthermore medication does nothing to address underlying psychosocial stressors that accompany CMD.

Overcoming Barriers

Both projects involved seeking permissions (with executive directors, health bureau, clinic heads), and forming and sustaining relationships with administrators, trainers, and learners. Adding psychotherapy to therapeutic repertoires offered an opportunity to expand the skills and competence of health learners and to improve their patients’ outcomes. The CE-to-Go Project addressed barriers to providing psychotherapy by integrating core psychotherapy techniques into primary mental health care with the objective of broadening clinical repertoires, rather than strictly adhering to an unmodified manualized protocol. Because the implementation of Western-developed psychotherapy approaches took place in Western-based community mental health settings, it was assumed that the psychotherapeutic principles and techniques being taught could be generalized without further adaptation.

Development of the Biaber Project, in contrast, is attempting to anticipate and overcome additional barriers to implementation by adapting the psychotherapeutic model of IPT. At the level of individual health workers and patients, the opportunity costs imposed by psychotherapy sessions, particularly the patient’s time away from work or family and the health worker’s time away from other clinical tasks, have necessitated a decrease in the duration and number of sessions. This modification is in keeping with other global mental health care packages in low income countries, where the number of psychotherapy or counseling sessions ranges between 3-8 (Belkin, et al., 2011; Chatterjee, et al., 2008; Patel & Sartorius, 2008; Patel, Simon, Chowdhary, Kaaya, & Araya, 2009; Patel, Weiss, et al., 2011). We collaboratively modified IPT over a period of six years to build a critical mass of teachers and to adapt the treatment and training processes to Ethiopian culture.

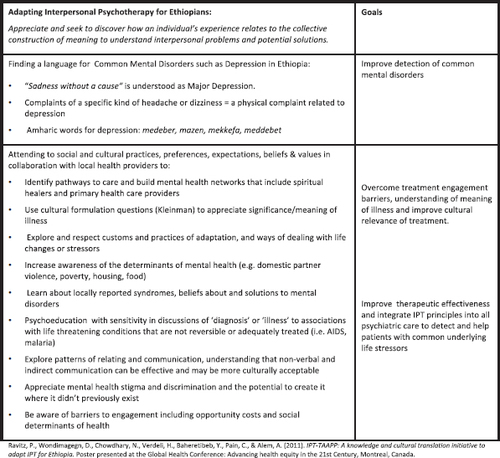

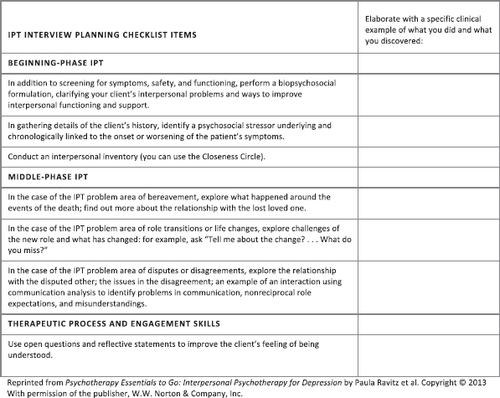

Adaptation of IPT for treatment of CMD by and for Ethiopians has attended to contextual and cultural factors, such as high clinical service demands and key social determinants of mental health (e.g., domestic violence and stigma). The adapted intervention, called IPT-E (Interpersonal Psychotherapy for Ethiopians), is a treatment for patients with CMDs in the context of the universal relational stressors of loss, life changes, or relational discord, and is recommended when CMD symptoms are persistent and at high levels. The training of the first tier of trainers has included longitudinal, interactive two-to-four week IPT training courses for psychiatry residents at Addis Ababa University (2006, 2008, 2011) and the Train-the-Trainers’ workshops for Ethiopian psychiatrists (2011, 2012). Clinical field testing and focus groups with 25 key informant Ethiopian psychiatrists from urban and rural settings provided feedback to improve treatment validity, acceptability, and relevance. Epidemiological and qualitative research also informed IPT’s cultural adaptation (Bass, et al., 2006; Bolton, et al., 2007; Bolton, et al., 2003; Patel, Weiss, et al., 2011; Patel et al., 2010). These initiatives shaped the cultural adaption of IPT for broad use in Ethiopian mental health and primary care settings (See Figure 1). Clinical guidelines for IPT-E appreciate the impacts of stressors, cultural traditions, and coping practices related to: (i) mourning (Bhugra & Becker, 2005); (ii) stigma toward suicidal behaviours (Alem, Jacobsson, et al., 1999) and comorbid medical illnesses, such as HIV or TB (Deribew et al., 2010; Feyissa, Abebe, Girma, & Woldie, 2012); (iii) specific life changes, such as becoming a new parent, when post-partum rituals can protect against the development of CMDs (Hanlon, et al., 2009), or migration experiences (Anbesse, Hanlon, Alem, Packer, & Whitley, 2009); and (iv) the tensions and dynamics of relational disputes for which long established community-based conflict resolution practices exist (e.g., referred to as Mamaker and Shemglena in Amharic), and where domestic partner violence may be present (Deyessa et al., 2009; Ellsberg, Jansen, Heise, Watts, & Garcia-Moreno, 2008; Garcia-Moreno, Jansen, Ellsberg, Heise, & Watts, 2006). IPT for Ethiopians fits well into the rich oral cultural tradition of personal and social problem resolution (see Figure 1). The Biaber Project’s scaling up of mental health care for people with CMD involves broadening treatment for primary health care patients using IPT-E in combination with antidepressant medication (if required). The Biaber Project training processes include multi-modal, case-based interactive teaching and longitudinal work-based clinical support/supervision with feedback using clinical checklists for learning, practice reminders, auditing and feedback. A treatment tracking form contains self-report adherence prompts for use in supervision to stimulate reflective discourse, clinical reasoning and learning in the process of implementing psychotherapeutic practice behavior changes. Figure 2 provides an example of an IPT-E therapist behavior checklist with adherence prompts for use in clinical supervision.

Figure 1. A KNOWLEDGE AND CULTURAL TRANSLATION INITIATIVE: IPT FOR ETHIOPIA

Figure 2. A PRACTICE REMINDER CHECKLIST FOR LEARNING AND SUPERVISION OF IPT

Learning Objectives and Trainers

The learning objectives of both projects include teaching the common factors of psychotherapies (e.g., empathy, therapeutic communication, the therapeutic alliance) (Norcross & Lambert, 2011) and model-specific psychotherapeutic principles and guidelines. The IPT-E specific learning objectives in the Biaber Project are driven by the new Ethiopian mental health strategy (Federal Democratic Republic of Ethiopia Ministry of Health, 2012) to disseminate mental health care into primary care, and the mhGAP guidelines that recommend IPT where it is available (World Health Organization, 2010). The evidence base establishing IPT as an effective and acceptable CMD treatment in other low income countries supports this approach (Patel V et al., 2010; Patel V et al., 2011; Bass et al., 2006; Bolton et al., 2007; Chatterjee et al., 2008), as does the years-long process of mental health training in Ethiopia from which the cultural adaptation of IPT emerged. In the Biaber Project, the trainers’ trainers are psychiatrists educated in IPT-E. Opinion leaders were to be recruited among psychiatric nurses in teaching hospitals as a second tier of teachers and to provide work-based clinical support and supervision of primary care workers in each related clinic. A third tier of opinion-leading peer-coaches, comprising primary care workers in each clinic setting, would sustain work-based clinical support.

The CE-to-Go Project determined learning needs and objectives through a two-step process. A list of curricular offerings was generated from prior surveys of mental health learning needs and consensus guide-line-recommended psychotherapies. Next, the project surveyed the front-line mental health workers and executive directors in the community-based mental health clinics where the project was being implemented. Respondents received a menu of educational offerings in evidence-supported psychotherapies and clinical challenges which they ranked according to level of interest, learning needs, and willingness to learn. The three highest ranked course offerings were cognitive therapy, IPT, and motivational interviewing. This project used small group teaching but did not involve longitudinal clinical supervision. Peer nominations selected opinion-leading course facilitators with the approval of each local clinic executive director (Ravitz, Cooke, et al., 2013).

Teaching Formats, Materials and Mentoring Guidelines

Both projects employ multimodal interactive lesson plans to stimulate reflection, discussion, and interactive learning, e.g., role-plays for skills practicing, and printed materials (with pocket-card summaries of clinical guidelines). Videotaped role-modeling of therapy simulations demonstrates model-specific therapeutic techniques, similar to other mental health scaling-up training projects (Chowdhary, Chatterjee, & Patel, 2011; World Health Organization, 2010b). The Biaber Project has a videotaped demonstration in the Amharic language. Seeing the modeling of clinical skills may diminish learners’ performance anxiety and reduce attitudinal barriers to changing practice.

The Biaber mentoring materials’ explicit guidelines related to nonstigmatizing care, with attention to the therapeutic alliance, provide a list of “dos and don’ts”(Wondimagegn, Ravitz, Pain, Alem, & Carey, 2013). The dos include: learning how and why a patient is suffering and how this affects their functioning; gaining a mutual understanding of the context (psycho-social stressors) in which symptoms arise; listening actively to a patient as s/he explains his or her personal understanding of illness or suffering; being respectful, empathic, compassionate and non-judgmental; sustaining confidentiality; focusing on helping each patient to recover; and ensuring a patient feels safe, understood, and cared for. The don’ts highlight breaches of professional boundaries. Every one of the CE-to-Go courses emphasizes the importance of both the common factors of psychotherapies (e.g., therapeutic alliances, empathy) along with skills-teaching of model-specific techniques.

The Biaber mentoring guidelines discuss the fundamentals of teaching with active listening, dialogue on clinical reasoning, questioning, and providing specific, instructive feedback within a positive educational milieu and learning alliance. Interacting with genuine interest and collegial respect models and helps the trainees to experience an alliance that facilitates reflection and learning—about mental health, its detection and treatment with adaptation to the local context. To “make learning stick,” and build upon learners’ previous knowledge, teaching can be enlivened with transparent thinking aloud, using illustrative clinical examples, anecdotes, metaphors and specific constructive feedback (Mori et al., 2008; Mori et al., 2011).

Conclusion

Psychotherapies of proven effectiveness to treat prevalent mental disorders are used too infrequently. Scaling up the implementation of these psychotherapies by training trainers and front-line lay and professional health workers can help to close gaps between mental health needs and care access. Improving dissemination of evidence-supported psychotherapies requires articulating specific learning objectives that adapt treatments to cultural and health organizational contexts, fostering a culture of psychological safety and learning, reducing implementation barriers (including opportunity costs and mental health stigma), and engaging local clinical opinion-leaders to teach using multi-modal, longitudinal, interactive, case-based teaching with reflection, skills-coaching, simulations, auditing and feedback with attention to learning and therapeutic alliances.

Psychotherapy supervision, CME and KT research-derived pedagogic recommendations can inform the planning and scaling up of psychotherapy treatment to link evidence-based clinical and education practices. Disseminating evidence-supported psychotherapies, such as IPT, using best-education practices has the potential to expand the therapeutic repertoire of health care workers and the clinical outcomes of the patients they treat thus reducing the gaps between mental health needs and care.

(1999). Trends in suicide, parasuicide and accidental poisoning in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. Ethiopian Journal of Health Development 13(3), 247–261.Google Scholar

(1995). Mental health in Ethiopia. Ethiopian Journal of Health Development(9), 47–62.Google Scholar

(2008). Community-based mental health care in Africa: mental health workers’ views. World Psychiatry, 7(1), 54–57.Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

(1999). Awareness and attitudes of a rural Ethiopian community toward suicidal behaviour. A key informant study in Butajira, Ethiopia. Acta Psychiatr Scand Suppl, 397, 65–69.Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

(1999). Suicide attempts among adults in Butajira, Ethiopia. Acta Psychiatr Scand Suppl, 397, 70–76.Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

(2010). Co-creating a psychiatric resident program with Ethiopians, for Ethiopians, in Ethiopia: the Toronto Addis Ababa Psychiatry Project (TAAPP). Acad Psychiatry, 34(6), 424–432.Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

(2009). Migration and mental health: a study of low-income Ethiopian women working in Middle Eastern countries. Int J Soc Psychiatry, 55(6), 557–568.Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

, (2010). Tailored interventions to overcome identified barriers to change: effects on professional practice and health care outcomes. Cochrane Database Syst Rev(3), CD005470.Medline, Google Scholar

, (2006). Group interpersonal psychotherapy for depression in rural Uganda: 6-month outcomes: randomised controlled trial. Br J Psychiatry, 188, 567–573.Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

(1979). Cognitive therapy of depression. New York, NY: Guilford Press.Google Scholar

(1961). An inventory for measuring depression. Arch Gen Psychiatry, 4, 561–571.Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

(2010). Training Therapists in Evidence-Based Practice: A Critical Review of Studies From a Systems-Contextual Perspective. Clinical Psychology-Science and Practice, 17(1), 1–30.Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

, (2011). Scaling up for the ‘bottom billion‘: ‘5 x 5’ implementation of community mental health care in low-income regions. Psychiatr Serv, 62(12), 1494–1502.Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

(2005). Migration, cultural bereavement, and cultural identity. World Psychiatry, 4(1), 18–24.Medline, Google Scholar

, (2007). Interventions for depression symptoms among adolescent survivors of war and displacement in northern Uganda: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA, 298(5), 519–527.Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

, (2003). Group interpersonal psychotherapy for depression in rural Uganda: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA, 289(23), 3117–3124.Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

(2001). Narrative medicine - A model for empathy, reflection, profession, and trust. Jama-Journal of the American Medical Association, 286(15), 1897–1902.Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

, (2008). Integrating evidence-based treatments for common mental disorders in routine primary care: feasibility and acceptability of the MANAS intervention in Goa, India. World Psychiatry, 7(1), 39–46.Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

(2011). The MANAS Model for Health Counselors: Managing Common Mental Disorders in Primary Care. Retrieved from: http://www.sangath.com/images/file/Health%20Counselor%20Manual.pdf.Google Scholar

(2013). Motivational Interviewing for Concurrent Disorders. New York, NY: W.W. Norton & Company.Google Scholar

(2008). Psychotherapy for depression in adults: a meta-analysis of comparative outcome studies. J Consult Clin Psychol, 76(6), 909–922.Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

(2010). Selecting educational interventions for knowledge translation. Canadian Medical Association Journal, 182(2), E89–E93.Crossref, Google Scholar

(2008). Continuing medical education: AMEE education guide no 35. Medical Teacher, 30(7), 652–666.Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

(2010). The synergy between TB and HIV co-infection on perceived stigma in Ethiopia. BMC Res Notes, 3, 249.Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

, (2009). Intimate partner violence and depression among women in rural Ethiopia: a cross-sectional study. Clin Pract Epidemiol Ment Health, 5, 8.Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

, (2011). Evidence-based guidelines for mental, neurological, and substance use disorders in low-and middle-income countries: summary of WHO recommendations. PLoS Med, 8(11), e1001122.Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

(2011). Empathy. Psychotherapy (Chic), 48(1), 43–49.Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

(2008). Intimate partner violence and women’s physical and mental health in the WHO multi-country study on women’s health and domestic violence: an observational study. Lancet, 371(9619), 1165–1172.Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

, (2012). Factors influencing responsiveness to feedback: on the interplay between fear, confidence, and reasoning processes. Advances in Health Sciences Education, 17(1), 15–26.Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

, (2012). A systematic review: the effect of clinical supervision on patient and residency education outcomes. Acad Med, 87(4), 428–442.Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

(2013). Cognitive Behavioral Therapy for Anxiety. New York, NY: W.W. Norton & Company.Google Scholar

(2013). Cognitive Behavioral Therapy for Depression. New York, NY: W.W. Norton & Company.Google Scholar

(2012). Stigma and discrimination against people living with HIV by healthcare providers, Southwest Ethiopia. BMC Public Health, 12, 522.Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

, (2011). Local opinion leaders: effects on professional practice and health care outcomes. Cochrane Database Syst Rev(8), CD000125.Medline, Google Scholar

, (2009). Continuing education meetings and workshops: effects on professional practice and health care outcomes. Cochrane Database Syst Rev(2), CD003030.Medline, Google Scholar

(2006). Prevalence of intimate partner violence: findings from the WHO multi-country study on women’s health and domestic violence. Lancet, 368(9543), 1260–1269.Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

, (2012). Printed educational materials: effects on professional practice and healthcare outcomes. Cochrane Database Syst Rev, 10, CD004398.Medline, Google Scholar

(2007). Some theoretical underpinnings of knowledge translation. Acad Emerg Med, 14(11), 936–941.Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

(2009). Postnatal mental distress in relation to the sociocultural practices of childbirth: an exploratory qualitative study from Ethiopia. Soc Sci Med, 69(8), 1211–1219.Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

, (1983). The WHO collaborative study on strategies for extending mental health care, II: The development of new research methods. Am J Psychiatry, 140(11), 1474–1480.Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

(2006). Development and validation of a revised short version of the Working Alliance Inventory. Psychotherapy Research, 16(1), 12–25.Crossref, Google Scholar

, (2010). A critical synthesis of literature on the promoting action on research implementation in health services (PARIHS) framework. Implement Sci, 5, 82.Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

(2010). The role of therapist training in the implementation of psychosocial treatments: a review and critique with recommendations. Clin Psychol Rev, 30(4), 448–466.Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

, (1988). Unpublished manuscript: Development of a system for rating therapies for depression.Google Scholar

(2011). Alliance in individual psychotherapy. Psychotherapy (Chic), 48(1), 9–16.Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

, (2012). Audit and feedback: effects on professional practice and healthcare outcomes. Cochrane Database Syst Rev, 6, CD000259.Medline, Google Scholar

(2009). Canadian Network for Mood and Anxiety Treatments (CANMAT) clinical guidelines for the management of major depressive disorder in adults. Introduction. J Affect Disord, 117 Suppl 1, S1–2.Medline, Google Scholar

, (2003). Screening for serious mental illness in the general population. Arch Gen Psychiatry, 60(2), 184–189.Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

(2007). AMEE Guide No. 27: Effective educational and clinical supervision. Med Teach, 29(1), 2–19.Google Scholar

(2008). Evaluating the successful implementation of evidence into practice using the PARiHS framework: theoretical and practical challenges. Implementation Science, 3.Medline, Google Scholar

, (2013). (Mis)perceptions of Continuing Education: Insights From Knowledge Translation, Quality Improvement, and Patient Safety Leaders. Journal of Continuing Education in the Health Professions, 33(2), 81–88.Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

, (2013). Positioning continuing education: boundaries and intersections between the domains continuing education, knowledge translation, patient safety and quality improvement. Advances in Health Sciences Education, 18(1), 141–156.Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

(2013). The disconnections between space, place and learning in interprofessional education: an overview of key issues. Journal of Interprofessional Care, 27, 5–8.Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

(1977). Depression, somatization and the ‘new cross-cultural psychiatry’. Soc Sci Med, 11(1), 3–10.Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

(1984). Interpersonal Psychotherapy of Depression. New York, NY: Basic Books Inc Publishers.Google Scholar

(2011). Collecting client feedback. Psychotherapy (Chic), 48(1), 72–79.Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

(1993a). Cognitive Behavioral Treatment of Borderline Personality Disorder. New York, NY: Guilford Press.Google Scholar

(1993b). Skills Training Manual for Treating Borderline Personality Disorder. New York, NY: Guilford Press.Google Scholar

(2009). Reflection and reflective practice in health professions education: a systematic review. Adv Health Sci Educ Theory Pract, 14(4), 595–621.Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

(2013). Dialectical Behavior Therapy for Emotion Dysregultion. New York, Ny: W.W. Norton & Company.Google Scholar

(2006). Assessing the relationships between contextual factors and research utilization in nursing: systematic literature review. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 55(5), 622–635.Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

(1983). Motivational interviewing with problem drinkers. Behavioural Psychotherapy, 11(2), 147–172.Crossref, Google Scholar

(1991). Motivational Interviewing: Preparing People to Change Addictive Behaviour. New York, NY: Guilford Press.Google Scholar

(2004). A randomized trial of methods to help clinicians learn motivational interviewing. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 72(6), 1050–1062.Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

, (2006). Outcome of major depression in Ethiopia: population-based study. Br J Psychiatry, 189, 241–246.Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

, (2008). TLC-Teaching for Learning and Collaboration: A Clinical Teaching Skills Faculty Development Program.,

, (2011). TLC-Teaching for Learning and Collaboration: A Multi-Professional Teaching Skills Program for Faculty Who Teach Health Professionals.

(1999). Perceptions of Mental and Physical Illnesses in North-western Ethiopia: Causes, Treatments, and Attitudes. J Health Psychol, 4(4), 531–549.Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

, (2011). Building capacity in mental health interventions in low resource countries: an apprenticeship model for training local providers. Int J Ment Health Syst, 5(1), 30.Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

(2011). Psychotherapy relationships that work II. Psychotherapy (Chic), 48(1), 4–8.Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

, (2013). Unpublished: The Biaber Project – Scaling up Interpersonal Psychotherapy (IPT) for Common Mental Disorders in Ethiopia. Grand Challenges.Google Scholar

(2011). Improving access to psychological treatments: lessons from developing countries. Behav Res Ther, 49(9), 523–528.Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

(2009). Scaling up services for mental and neurological disorders in low-resource settings. Int Health, 1(1), 37–44.Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

(2008). From science to action: the Lancet series on global mental health. Current Opinion in Psychiatry, 21(2), 109–113.Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

(2009). Packages of care for depression in low-and middle-income countries. PLoS Med, 6(10), e1000159.Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

, (2011). Lay health worker led intervention for depressive and anxiety disorders in India: impact on clinical and disability outcomes over 12 months. Br J Psychiatry, 199(6), 459–466.Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

, (2010). Effectiveness of an intervention led by lay health counsellors for depressive and anxiety disorders in primary care in Goa, India (MANAS): a cluster randomised controlled trial. Lancet, 375(9758), 2086–2095.Crossref, Google Scholar

, (2007). Global mental health 1 - No health without mental health. Lancet, 370(9590), 859–877.Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

, (2013). Continuing Education To Go: Capacity Building in Psychotherapies for Front-Line Mental Health Workers in Underserviced Communities. Canadian Journal of Psychiatry-Revue Canadienne De Psychiatrie, 58(6), 335–343.Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

Ravitz, P.Maunder, R. (Eds.). (2013). Psychotherapy Essentials to Go. New York: W.W. Norton & Company.Google Scholar

(2013). Interpersonal Psychotherapy for Depression. New York, NY: W.W. Norton & Company.Google Scholar

, (2011). IPT-TAAPP: A knowledge and cultural translation initiative to adapt IPT for Ethiopia.:

(2004). The PARIHS framework–a framework for guiding the implementation of evidence-based practice. J Nurs Care Qual, 19(4), 297–304.Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

(2009). The use of reflection in medical education: AMEE Guide No. 44. Med Teach, 31(8), 685–695.Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

(2011). CPD and KT: models used and opportunities for synergy. J Contin Educ Health Prof, 31(3), 167–173.Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

(2009). Reflection: a link between receiving and using assessment feedback. Adv Health Sci Educ Theory Pract, 14(3), 399–410.Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

(2002). Iatrogenic stigma of mental illness. BMJ, 324(7352), 1470–1471.Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

(2007). Stigma and mental health. Lancet, 370(9590), 810–811.Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

(1983). The Reflective Practitioner: How Professionals Think In Action. New York: Basics Books.Google Scholar

(2005). We don’t train in vain: A dissemination trial of three strategies of training clinicians in cognitive-behavioral therapy. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 73(1), 106–115.Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

(1995). The interpersonal relationship in clinical practice. The Barrett-Lennard Relationship Inventory as an assessment instrument. Eval Health Prof, 18(1), 103–112.Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

(2011). Culture. J Clin Psychol, 67(2), 166–175.Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

(2009). Defining knowledge translation. CMAJ, 181(3–4), 165–168.Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

(2012). The Stigmatization of Mental Illnesses. Canadian Journal of Psychiatry-Revue Canadienne De Psychiatrie, 57(8), 455–456.Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

(2013). Perceived need for mental health care in Canada: Results from the 2012 Canadian Community Health Survey-Mental Health. Health Reports, 24(9), 3–9.Medline, Google Scholar

(2007). Discrimination in health care against people with mental illness. Int Rev Psychiatry, 19(2), 113–122.Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

(1972). The meaning and reliability of accurate empathy ratings: a rejoinder. Psychol Bull, 77(6), 397–399.Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

(1986). The cognitive therapy scale - psychometric properties. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 54(3), 381–385.Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

, (2013). Non-specialist health worker interventions for the care of mental, neurological and substance-abuse disorders in low-and middle-income countries. Cochrane Database Syst Rev, 11, CD009149.Medline, Google Scholar

, (2003). Adapting group interpersonal psychotherapy for a developing country: experience in rural Uganda. World Psychiatry, 2(2), 114–120.Medline, Google Scholar

(2008). Treatment failure in psychotherapy: The pull of hostility. Psychotherapy Research, 18(4), 420–432.Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

(2013). The state of psychotherapy supervision: recommendations for future training. Int Rev Psychiatry, 25(3), 255–264.Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

(2013a). Psychotherapy: a paradox. Am J Psychiatry, 170(7), 712–715.Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

(2013b). Psychotherapy: Increasing in Poor Countries, Decreasing in the United States. Retrieved November 14, 2013, from http://www.huffingtonpost.com/myrna-m-weissman-phd/psychotherapy-low-income-countries_b_3991151.htmlGoogle Scholar

(2007). Clinician’s Quick Guide to Interpersonal Psychotherapy USA: Oxford University Press.Crossref, Google Scholar

, (2006). National survey of psychotherapy training in psychiatry, psychology, and social work. Arch Gen Psychiatry, 63(8), 925–934.Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

, (2013). Global burden of disease attributable to mental and substance use disorders: findings from the Global Burden of Disease Study 2010. Lancet, 382(9904), 1575–1586.Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

(2013). Unpublished: The Biaber Project Training MaterialsGoogle Scholar