Is Interpersonal Psychotherapy Infinitely Adaptable? A Compendium of the Multiple Modifications of IPT

Abstract

We employed standard literature search techniques and surveyed participants on the International Society for Interpersonal Psychotherapy listserve (isipt-list@googlegroups.

The First Author Reflects on Thirty Years of Experience with IPT

When introduced to interpersonal psychotherapy, I was a deeply committed cognitive therapist. I found the tightly linked theoretical rationale and strategies and tactics of cognitive therapy (CT)—especially as taught and supervised by a charismatic Marika Kovacs, fresh from Aaron Beck’s group—a firm landing place compared to the essentially model-free forms of psychotherapy that clinical psychology programs were teaching in the mid-70s.

I only learned IPT because I had to. We were about to initiate a study of maintenance therapies in recurrent depression using IPT, and I had been drafted to monitor therapist adherence to the model. The study therapists and I had the great fortune to have Gerald Klerman and Myrna Weissman do our didactic training. I then had the equally good fortune to receive individual supervision of two (impossibly difficult) cases from Bruce Rounsaville. Still, in comparison to CT, IPT seemed very ‘soft.’ It was what my social worker mother did with her clients, not really a psychotherapy.

Being an empiricist, slowly but surely I was converted by my clinical experiences, by those of our study therapists and, most of all, by the data emerging from our study. Interpersonal psychotherapy worked! And it was flexible. In our clinical psychology clinic, I had many clients who for one reason or another just could not ‘get’ CT: they were too concrete to be able to think about their thoughts, too poorly educated to record them, too worried about where their next meal was coming from or whether they would still have a roof over their heads when next we met to find any mastery or pleasure experiences in their lives. But in our study we seemed to be able to make IPT ‘fit’ all of these lives.

More than 30 years later, I remain amazed by the adaptability of IPT and wonder why it appears to be so adaptable. I think back to those New Haven social workers from whose interventions the first prototype of IPT derived. These clinicians, who, like my mother—a gifted clinical social worker—recognized the centrality of social relations and social roles in health and wellbeing. They believed that if you help to repair a person’s social relations and find satisfaction in social roles, many kinds of suffering can be relieved.

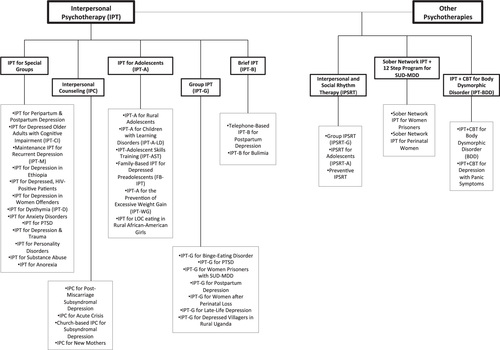

Almost from its earliest days, IPT has been a highly flexible model upon which practitioners and researchers have built to meet the needs of specific patient populations. Early on, Klerman and colleagues created interpersonal counseling (IPC), a brief intervention initially intended for use in primary care (Klerman et al., 1987; See Weissman et al., this issue). Our own group created maintenance interpersonal psychotherapy [IPT-M] to meet the needs of the maintenance phase of the study mentioned above (Frank et al, 1990; Frank, Kupfer, Cornes & Morris, 1993). Mufson and her colleagues adapted IPT for adolescents (IPT-A— Mufson, Moreau, Weissman, & Klerman, 1993; Mufson et al., 1994; see Mufson et al., this issue), while Wilfley and colleagues developed a group format ([IPT-G] Wilfley, Mackenzie, Welch, Ayres, & Weissman, 2000). More recently, Swartz and colleagues saw a need for a briefer intervention for individuals whose depressions were being maintained by the very demands that precluded involvement in a course of therapy that would require the more usual 12 to 16 weeks (IPT-B—Swartz et al., 2004). From these “primary” adaptations other modifications have flowed, addressing the needs of specific clinical populations or cultural groups. The seminal adaptations have paved the way for newer investigators to explore the breadth of possibilities that IPT offers. In this report, we first describe the remarkable array of innovative treatments that flowed from these direct descendants of the original IPT model (See Figure 1).

Figure 1: The Interpersonal Psychotherapy Family

In addition, several groups have created what might be thought of as “in-laws:” therapies that have “married” IPT with other interventions and have, thus, joined the IPT family of therapies. The second part of this report describes these hybrid treatments, several of which now have substantial evidence of efficacy.

Note that we do not review the many interesting settings and populations in which the original IPT model has since been applied without adaptation. Rather, this report focuses on the creative ways in which the original model has been adapted.

Adaptations of the Original IPT Model for Specific Populations

IPT for Peripartum and Postpartum Depression

Not surprisingly, given the IPT emphasis on relationships and roles, research groups have made slight changes to IPT to meet the needs of pregnant and postpartum women with depression. Spinelli was initially interested in IPT to treat women who were depressed during pregnancy. A pilot trial (Spinelli, 1997) in which all nine participants who completed the trial showed remission of depressive symptoms, provided the impetus for further studies. Her subsequent studies demonstrated superior efficacy of IPT over a parenting education program in two randomized controlled trials (RCTs) with diverse groups of women (Spinelli & Endicott, 2003; Spinelli et al., 2013).

Around the same time, O’Hara and Stuart began to study IPT for postpartum depression ([PPD]; O’Hara, Stuart, Gorman, & Wenzel, 2000; Stuart & O’Hara, 1995). Postpartum depression fits particularly well the biopsychosocial model of disease on which IPT is based. Mothers generally understand the dramatic changes in hormones and physiology, daily activities, and social roles that accompany birth, but may need help from a therapist to understand how these changes contribute to depressive symptoms. O’Hara et al. modify the strategies and tactics of IPT only slightly. They emphasize the relationship of the new mother with her infant, noting that women may be reluctant to acknowledge negative feelings toward their children for fear of being perceived as bad mothers. Thus, the therapist carefully elicits the patient’s full range of emotions. Another important and dynamic relationship to discuss is that between the mother and her partner, which is addressed by including the partner in at least two sessions for psycho-education on psychological and physiological changes associated with birth to help resolve any interpersonal issues that arise. Finally, the therapist may be more directive than normal in offering practical advice for logistical issues in caring for the child (Stuart, 2012).

In 2000, O’Hara, Stuart, & colleagues reported on a randomized controlled trial of 120 depressed postpartum women. Those who received IPT showed significantly greater decreases in depressive symptoms than those in the waitlist control group, and a significantly greater proportion of women in the IPT condition met criteria for remission than in the control condition (O’Hara, Stuart, Gorman, & Wenzel, 2000). Other researchers have adapted IPC and group IPT for this population, which will be described later.

IPT for Depressed Older Adults with Cognitive Impairment (IPT-CI)

Miller and Reynolds (2007) noted that treating depression in older adults is particularly challenging when cognitive decline accompanies the depression. They developed an adaptation of IPT that involves both the caregiver and the patient who has cognitive impairment and depression. Miller and Reynolds (2007) viewed IPT as uniquely suited for this population, in which the patient’s increasing dependence on the caregiver constitutes a role transition for both parties. This model offers caregivers help in understanding the patient’s capabilities and guidance in problemsolving with patients who need complex tasks broken down into more manageable steps. Therapists may meet with caregivers one-on-one to discuss patients’ problem behaviors, as well as fears and anxieties the caregiver may feel. The focus on the role transition for the patient is somewhat modified, as it is often not possible to replace lost capabilities with new ones. Instead, the therapist helps the patient focus on intact areas of function while accepting the shift to dependency.

In a 2007 pilot study, Miller & Reynolds assessed the feasibility of social workers administering this treatment in an ambulatory geriatric clinic. Though the sample size was too small to conduct formal analyses, the participants demonstrated meaningful decreases in depressive symptoms during the treatment (M. Miller, personal communication, December 2, 2013).

Maintenance IPT for Individuals with Recurrent Depression

Our research group modified IPT for the preventive maintenance treatment of adults with recurrent depression (IPT-M). The major adaptations comprised the timing of the sessions (monthly), focus on the prevention of future interpersonal and social role problems, discussion of the patient’s personal early warning signs of episode onset, and greater emphasis on addressing ongoing, if mild, interpersonal deficits. This adaptation was compared to maintenance pharmacotherapy, the combination of pharmacotherapy and IPT-M, and placebo and clinical management. The effects of pharmacotherapy and the combination treatment did not differ and had the best preventive outcomes in this three-year trial; however, compared to placebo and clinical management, IPT-M was associated with significant protection against new depressive episodes (Frank et al, 1990).

Further adaptations were made this model for a study of recurrent depression in late life. These included briefer sessions when necessary and allowing more time for reminiscence about the past, particularly past accomplishments. This trial found a modest benefit of combination over pharmacotherapy alone, and IPT-M was significantly superior to clinical management and placebo (Reynolds et al, 1999; 2006).

IPT for Treating Depression in Ethiopia

Ravitz, Wondimagegn and colleagues (2011) have adapted IPT for use in Ethiopia with the Toronto-Addis Ababa Psychiatry Project (TAAPP). Adaptations included incorporating an understanding of locally reported syndromes and beliefs about their origin and cure; exploring customs traditionally associated with IPT problem areas; altering language to emphasize the treatability of depression symptoms, and decreasing the number, frequency, and duration of sessions (Ravitz et al., 2011). Additional information about this adaptation is provided in the Ravitz et al. paper in this issue.

IPT for Depressed HIV-Positive Patients

In the early 1990s Markowitz and colleagues adapted IPT to treat depressed HIV-seropositive patients (Markowitz, Klerman, Perry, Clougherty, & Josephs, 1993). Developed before effective treatments for HIV were broadly available, when HIV appeared almost invariably fatal, in this adaptation psychoeducation focused on having two medical illnesses, HIV and depression, the latter highly treatable. The model acknowledged that the depression may have developed as a consequence of having an HIV diagnosis, and the probability that the syndrome would shorten the patient’s life, creating an ongoing “sick role.” Patients were encouraged to mourn their losses and to make the most of the life that remained to them. Originally used in a pilot study of 24 depressed seropositive patients in which 88% recovered from their depression (Markowitz et al., 1993), this adaptation was tested in a study of 101 HIV-positive patients with depressive symptoms comparing IPT, CBT, supportive psychotherapy (SP), or imipramine plus SP. While all four groups improved, depressive symptoms improved significantly more for IPT or imipramine plus SP than for CBT or SP alone (Markowitz et al., 1998; Adapted from Frank & Levenson, 2011 p. 103).

More recently, Ransom and Heckman have studied telephone-based IPT for rural patients with HIV and depression. In addition to shifting from in-person to phone treatment, they shortened the number of sessions from 12 to 6. In their study, the IPT group significantly improved in depression and psychiatric distress; about 1/4 of participants in IPT group demonstrated clinically meaningful changes (Ransom et al., 2008).

IPT for Depression in Women Charged Witih Low-Level Offenses

Black and colleagues are currently testing a protocol for depressed women who have recently committed low-level crimes, aiming to reduce the likelihood of reoffending by treating the depression (S. Black, personal communication, November 20, 2013). Their version includes several modifications designed for this group including proactive engagement strategies: text reminders for appointments and explicit discussion of how the patients feel about the treatment and their reasons for lateness or absence. During psycho-education, the therapist reiterates the importance of regular, timely attendance and encourages the patient to inform the clinic in advance if she cannot make an appointment. To accommodate logistical difficulties in attendance, the center provides bus tickets, childcare, and refreshments. In anticipating potentially harmful interpersonal contexts, the therapist assesses whether the woman’s risk to herself and risk from others and helps create a safety plan that is reviewed at every session.

IPT for Dysthymia

Markowitz adapted typical IPT for the treatment of dysthymia ([IPT-D] 1996, 1998). Though dysthymia is often seen as less severe than major depressive disorder (MMD), its enduring, chronic nature, makes it more difficult to treat than MDD. A crucial component of treating dysthymia is legitimizing the sick role: because patients have felt “down in the dumps” for extended periods of time, they may attribute their symptoms to an inherent character flaw, rather than a treatable disease. This adaptation involved the transformation of the interpersonal deficits problem area to an “iatrogenic role transition” problem area in which the acknowledgement of dysthymia as a treatable condition enables the patient to experience a pervasive role transition (Mason, Markowitz, & Klerman, 1993). In an RCT comparing IPT-D with medication, IPT plus medication, and brief supportive therapy, all groups showed significant improvement from baseline to post-treatment, although the treatment groups receiving medication improved more than the pure psychotherapy groups (Markowitz, Kocsis, Bleiberg, Christos, & Sacks, 2005).

De Mello and colleagues conducted an RCT comparing IPT and medication vs. medication alone for individuals with dysthymia and multiple comorbidities (including MDD and various anxiety disorders) living in the favelas of Sao Paulo. Both groups improved to about the same degree during treatment; however, the IPT group showed continued improvement at follow-up (de Mello, Myczowisk, & Menezes, 2001).

IPT for Anxiety Disorders

Some adaptations of the original individual treatment for depression have focused on treating other disorders, particularly anxiety disorders. Lipsitz and colleagues (2006) modified IPT for panic disorder (IPT-PD). A key strategy involves linking the patient’s panic symptoms to his or her interpersonal situation. In an uncontrolled pilot study, participants receiving IPT-PD showed significant improvement in panic symptoms, anxiety sensitivity, anxiety and arousal, depression, and emotional well-being (Lipsitz et al., 2006).

This group also used IPT to treat social anxiety disorder or social phobia (Lipsitz, Markowitz, & Cherry, 1997). As in IPT for dysthymia, the patient is encouraged to transition from a view of himself as an internally flawed person to that of someone with a treatable condition. Lipsitz and colleagues note that “a temperamental predisposition interacts with early and later life experiences to initiate and maintain” the social anxiety (Lipsitz et al., 2008, p. 544). Their 2008 RCT included 70 individuals with social anxiety who received 14 sessions of IPT-SP or supportive therapy. They found IPT had an outcome equivalent to supportive therapy, although they noted that individuals with such long-standing problems may require a longer course of IPT. They also found that IPT may be more applicable to conditions that have a more recent or more acute onset and subsequently noted that in trials where the same therapists delivered both interventions, there may be contamination across conditions (Sinai & Lipsitz, 2012).

Several groups of researchers around the world have also explored the utility of IPT for anxiety disorders. Huang and Liu compared group IPT and group CBT for social anxiety disorder (SAD) in Chinese college students and found both therapies equally effective (2011), Stangier and colleagues in Germany found IPT efficacious for SAD, though inferior to cognitive therapy ([CT] 2011). In Norway, Borge and colleagues compared IPT-G to CT-G in a residential setting for patients with social phobia who had been unsuccessfully treated in an outpatient clinic. Patients in both groups demonstrated significant improvements in anxiety at posttreatment and further improvements at a 1-year followup (Borge et al., 2008). Finally, Vos and colleagues compared IPT with CBT for panic disorder with agoraphobia in the Netherlands, and found CBT the superior treatment (2012). While findings are mixed and very preliminary, there is some suggestion that IPT may be a stronger treatment for social anxiety than for panic disorder. Considering the central role of interpersonal difficulties in SAD, it is not surprising that IPT would be an effective treatment (Frank & Levenson, 2011 pp. 96-97).

IPT for Posttraumatic Stress Disorder

Interpersonal psychotherapy is also being tested for posttraumatic stress disorder. While most empirically validated treatments for posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) involve exposure to stimuli that are reminders of a traumatic event, several groups of investigators have modified IPT to treat PTSD or for individuals whose posttraumatic symptoms represent prominent clinical features. Bleiberg and Markowitz (2005) conducted a pilot study treating 14 adults with PTSD with 14 weeks of IPT adapted to focus on the interpersonal sequelae of trauma. Although uncontrolled, the study indicated that IPT was associated with marked reduction in PTSD symptoms. Approximately 40% of participants achieved remission, and almost 70% were considered treatment responders, suggesting that exposure may not be a necessary component of successful PTSD treatment. Markowitz and colleagues [in press recently completed an RCT of this intervention compared to prolonged exposure as well as relaxation therapy. Results are forthcoming.

Krupnick (2010) has been exploring the utility of an individual IPT model in women veterans with PTSD. She conducted an open trial with 15 women, ten of whom completed the study. Among those who completed the study, nine had a notable extent of comorbid depression and panic. The 12-session intervention was associated with significant reduction of PTSD symptoms and improvements in interpersonal functioning at posttreatment. Most participants focused on either role disputes or social isolation in their treatment (Krupnick, 2010; (Frank & Levenson, 2011, pp. 97-98).

IPT for Depressed Women with a History of Trauma

In community mental health centers, a large segment of patients seeking care are depressed women who have extensive trauma histories (though they do not meet full criteria for PTSD). Depression in this population typically has a chronic and treatment-refractory course, and is accompanied by other disorders and challenges. Talbot & colleagues (2005) tested IPT among depressed women with sexual abuse histories in a community mental health center. They added four components to address the needs of this population: an expanded duration of treatment, an interpersonal-patterns problem area substituted for the interpersonal deficits, a sociocultural formulation, and an engagement analysis. The expanded treatment duration matches the realities of attendance patterns in a community health care center. Pilot studies indicated that poor treatment participation was strongly influenced by social barriers, especially the stigma of mental health care and shame associated with trauma histories. The engagement analysis uses IPT strategies in initial sessions to help patients overcome barriers to treatment participation. The sociocultural formulation elaborates the IPT formulation, focusing on cultural influences on patients’ interpersonal problems and depression among low income minority women. Finally, the interpersonal-patterns problem area is a trauma-specific modification intended to address chronic interpersonal patterns associated with a history of interpersonal trauma. An RCT of this IPT adaptation indicated significantly greater improvements in depressive symptoms, PTSD symptoms, and shame than patients in usual care (Talbot et al. 2011).

Toth and colleagues (2013) have also found IPT benefitted economically disadvantaged mothers with major depression and significant trauma histories. For this population, which does not seek treatment, the principal modifications made to IPT were to explain depression as a common set of feelings associated with the many challenges parents face in childrearing. At times, therapists used language focused on “feeling overwhelmed, stressed and down” because some participants had difficulty acknowledging that they felt depressed. For similar reasons, the psychoeducation that IPT therapists typically provide at the outset of treatment was sometimes delayed until the therapeutic alliance was stronger. Furthermore, therapists worked with participants to determine the least stressful service delivery venue, with options including their homes, an area in their community, or even the therapist’s car. Approximately 85% of participants were seen outside the clinic, with most such sessions taking place in homes. With these modifications, adherence to IPT was remarkably high and outcomes were positive. All 60 participants assigned to IPT received a full course (12 to 14 sessions) of treatment and had significantly greater improvement in their depression than those allocated to enhanced community treatment consisting of supported referral (Toth et al., 2013). Unfortunately, these modifications may be challenging to implement in general clinical practice (Frank & Levenson, 2011,p. 116).

IPT for Personality Disorders

Klerman and colleagues explicitly argued in their 1984 manual that brief IPT was not intended to effect “personality change.” More recently, however, several investigative groups, including some of those originally trained by Klerman and Weissman, have attempted to adapt IPT for treatment of personality disorders (Markowitz, Bleiberg, Pessin, & Skodol, 2007; Bellino, Zizza, Rinaldi, & Bogetto, 2007)] Despite disappointing results from an earlier trial (Angus & Gillies, 1994) that was largely focused on the depressive symptoms experienced by those with borderline personality disorder (BPD), Markowitz, Skodol, and Bleiberg (2006) adapted IPT for borderline personality disorder (BPD). They note that IPT may be especially suited to treating this population because of the highly interpersonal nature of the problems patients with BPD experience. Prominent in this IPT adaptation are a focus on termination issues from the very outset of treatment, longer treatment duration, and clear attention to the chronicity of the disorder, the high risk for suicidal behavior, and the potential difficulties in establishing a treatment alliance. A very small, preliminary open trial showed positive results, with the five patients who completed treatment all in remission by the end of treatment (Markowitz, Bleiberg, Pessin, & Skodol, 2007).

Markowitz, Skodol, and Bleiberg’s (2006; 2007) claim received some support from a subsequent study comparing IPT and CBT as treatments for individuals with depression and BPD, in which individuals (n=32) received either IPT plus pharmacotherapy or CT plus pharmacotherapy for 24 weeks (Bellino, Zizza, Rinaldi, & Bogetto, 2007). They found no difference between groups in proportions of participants who remitted from depression; however, IPT patients showed greater improvement in social functioning and in the domineering/controlling and intrusive/needy domains of the Inventory of Interpersonal Problems (Frank & Levenson, 2011, p. 99).

IPT for Substance Abuse

While there has been consistent interest in utilizing IPT as a treatment for substance abuse since its development, this is an area where IPT has been less successful. Bruce Rounsaville, one of the original developers of IPT, applied essentially unmodified IPT to cocaine abusers in the 1980s based on the rationale that interpersonal problems may constitute a major precipitant of substance use (Rounsaville, Gawin, & Kleber, 1985). He found that study participants were difficult to recruit and retain (Rounsaville, Glazer, Wilber, Weissman, & Kleber, 1983) and ultimately concluded that IPT was less successful at treating study participants than other active treatments (Carroll, Rounsaville, & Gawin, 1991; Carroll et al., 2004).

Despite these initial discouraging results, more recently Markowitz, Kocsis, Christos, Bleiberg, and Carlin (2008) investigated the effectiveness of IPT-D as compared to brief supportive therapy (BSP) for 26 individuals with dysthymic disorder and alcohol abuse. The IPT group demonstrated greater improvement in depressive symptoms and both groups reported increased abstinence; however, the improvement in alcohol abuseuse occurred at study entry, and thus cannot be attributed to IPT. While IPT-D did not appear to influence alcohol abuse, the presence of alcohol abuse did not interfere with effective treatment of depressive symptoms (Frank & Levenson, 2011, p. 100).

IPT for Anorexia

McIntosh and colleagues adapted IPT for anorexia nervosa (AN) from the original IPT for depression and Fairburn’s (1991) protocol for bulimia. Similar to the protocol for bulimia, therapists did not conduct a systematic review of AN symptoms, though some symptoms would be discussed as they related to the interpersonal problem area. In an RCT comparing IPT to CBT as well as nonspecific supportive clinical management (SSCM), the results unexpectedly showed that IPT was the least effective treatment while the control condition (SSCM) was the most effective (McIntosh et al., 2005). The authors hypothesized that symptoms of anorexia may not be causally related to interpersonal triggers, and thus the focus on interpersonal problems was insufficient to alter AN symptoms. However, in a follow-up study conducted by the same group in 2011, the participants in the IPT condition had shown the greatest improvement from post-treatment to follow-up, while participants in the SSCM condition had deteriorated significantly (Carter et al., 2011). In previous studies, IPT has taken longer to have an effect than CBT (Fairburn et al., 1991) which may have contributed to some of the later improvements. Due to these mixed results, further work is necessary to investigate the use of IPT for anorexia.

Interpersonal Counseling—IPC

Shortly after its initial development, Klerman and Weissman adapted IPT for treating depression in primary care settings. The treatment format was similar to IPT but condensed to six or fewer sessions, with a script for use by nurses not trained in mental health care, and with the middle sessions focusing on coping strategies and on discouraging dependency. A pilot study comparing IPC to a control group with no assigned mental health care found IPC patients significantly more likely to report absence of psychological distress than those in the control condition. These data suggest that IPC can be a clinically useful treatment for primary care patients with moderate psychological distress. (For a more in-depth look at the efficacy of IPC, see Weissman et al., this issue.)

The IPC model lay dormant for decades, but recently several groups of investigators have begun to apply it in creative ways. Neugebauer and colleagues used IPC in an open trial for subsyndromal depression following miscarriage, with preliminary success (Neugebauer et al., 2007). Lemaigre has modified IPC for individuals with high levels of self-harm and suicidality who are in acute crisis. A trained nurse works to identify social/interpersonal contexts associated with the onset of the acute crisis. Treatment consists of four 30 to 45 minute sessions and includes a comprehensive risk assessment in the first session (C. Lemaigre, 22 November, 2013). Hankerson is developing a project to train clergy in African American churches in New York City to deliver IPC to congregants with depressive symptoms, This uses using a three session model (S. Hankerson, personal communication, December 4, 2013). Wroblewska is developing a transdiagnostic model for intervention with new mothers in an in-patient mother and baby unit in the UK (A. Wroblewska, personal communication, October 29, 2013).

IPT for Adolescents—IPT-A

Mufson and Moreau modified IPT for adolescents (IPT-A) after noting that most cases of depression have roots in adolescence, and that the brief, present- and future-focused treatment seems ideally suited for adolescents (Moreau, Mufson, Weissman, & Klerman, 1991). Because adolescent depression is so often associated with drug abuse and suicidal behaviors, these issues receive special attention during assessment. The therapist engages the parents early in treatment to educate them about depression and to form an alliance for support. The therapist may contact the school to communicate the effects of depression on school performance and to monitor attendance. Flexibility in scheduling sessions over the phone often helps to accommodate changing schedules.

The strategies and tactics associated with the four problem areas are somewhat modified. For grief, one goal is to help the adolescent develop coping strategies to prevent future depressive episodes. Role disputes occur most often with parents; the therapist works to help the adolescent resolve conflicts within the family except in cases of abuse. Problematic role transitions, including changes in family structure through separation or divorce, are common and may require family support. The termination phase may involve a family session to review changes in symptoms and relationships and to educate the family about differences between shortterm symptom recurrence and full-blown relapse (Mufson, Dorta, Moreau, & Weissman, 2004). (For information on cultural factors moderating IPT-A outcomes, see Mufson et al., this issue.)

IPT-A for Adolescents in Rural Areas

Bearsley-Smith and colleagues (2007) identified the importance of studying the feasibility and effectiveness of IPT for treating adolescents with depression in a rural mental health service. IPT has been identified as effective for treating depressed adolescents in urban areas. A progression of studies demonstrated first its efficacy, then its effectiveness and, finally, its disseminability (Mufson et al., 1994; 1996; 1999; 2004), yet patients seen in a rural mental health service often present with more severe depression complicated by comorbid disorders and may face limited available mental health treatment. Sixty adolescents in rural Victoria, Australia received either 12 weeks of IPT-A or treatment as usual (TAU) with the intention of determining which treatment yielded a greater decrease in depressive symptoms and to assess the feasibility of implementing IPT in a rural mental health setting. The investigators found it feasible to implement IPT-A in a rural mental health setting, and found no differences between the two treatment groups on measures of depressive symptoms (C. Bearsley-Smith, personal communication, December 10, 2014; Frank & Levinson, 2011, pp. 106–107).

IPT-A for Children with Learning Disorders (IPT-A-LD)

Brunstein-Klomek, in Israel, has adapted IPT-A for children with learning disorders (LD) and clinical/subclinical depression symptoms (IPT-A-LD). A tenet of the model is that how a child/adolescent deals with LD is related to both the interpersonal context and to depression symptoms. The goals of this adaptation are to learn to deal better with the learning disorder, decrease depressive symptomatology, and improve interpersonal functioning. IPT-A-LD adds psychoeducation on LD. During the initial phase, IPT-A-LD includes a school meeting with the student, parents, and school staff. This meeting strengthens cooperation and the support network. During the middle phase adolescents with LD learn and practice cognitive skills, such as goal-setting. This includes realistically understanding the steps involved in accomplishing a task and how these can be achieved, and organization, focusing on the ability to plan and manage task demands, and making order of space, time, and materials. This group is currently conducting a feasibility study, with results to come (A. Brunstein-Klomek, personal communication, November 11, 2013).

IPT for Prevention of Depression in Adolescents

Young and colleagues developed interpersonal psychotherapy—adolescent skills training (IPT-AST) from the group IPT-A manual (Mufson, Gallagher, Dorta, & Young, 2004) as a preventive group treatment for adolescents at risk for developing MDD. Modifications included fewer sessions (eight), adding activities to demonstrate social contingencies, and using fictional scenarios to teach IPT techniques prior to exposure to real-life scenarios (Young & Mufson, 2003). In two RCTs comparing IPT-AST to typical school counseling (SC) for adolescents with subthreshold depressive symptoms, the IPT-AST condition showed significantly greater decreases in depressive symptoms and improvements in functioning (Young, Mufson, & Davies, 2006; Young, Mufson, & Gallop, 2010). However, by 12-month follow up, differences between groups in depressive symptoms had disappeared, suggesting that IPT-AST may help adolescents improve their symptoms of depression and overall functioning more quickly than normal school counseling, even if it is not more effective in the long term (Young et al., 2010).

Family-Based IPT (FB-IPT) for Depressed Preadolescents and their Families

Depression in preadolescence increases the risk for it recurrence in adolescence and adulthood, particularly when there is a strong family history of depression. Dietz and colleagues (2008) developed and piloted a family-focused, developmentally appropriate modification of IPT-A for depressed preadolescents and their parents (see Dietz, Mufson, Irvine, & Brent, 2008). Although the Family-Based Interpersonal Psychotherapy (FB-IPT) adheres to the structure and guiding principles of IPT-A, problem areas have been expanded to reflect the family or developmental context and to facilitate the dyadic discussion of the effect of interpersonal stressors on mood and depressive symptoms. FB-IPT modifications include: 1) increasing the number of conjoint parent sessions and dyadic sessions; 2) utilizing narrative techniques; and 3) increasing graded interpersonal experiments for patients with comorbid anxiety disorders. In a preliminary randomized controlled trial, 40 preadolescents with depression were allocated to FB-IPT or Client Centered Therapy (CCT), a supportive nondirective treatment that approximates standard care for pediatric depression in community mental health. After controlling for pretreatment scores, FB-IPT was associated with significantly lower clinician-rated and child- and parent-reported indices of depression at posttreatment than CCT. Preadolescents and parents in the FB-IPT treatment condition endorsed significant decreases in parent-child conflict, peer avoidance, and social anxiety compared to preadolescents and parents in CCT (Dietz, Mufson, & Weinberg, personal communication, December 17, 2013). Although preliminary results are promising, further research on FB-IPT is needed to establish its efficacy, its effectiveness by child clinicians with varying levels of training, and in adequately powered randomized controlled trials (Frank & Levenson, 2011, p. 114).

IPT for Prevention of Excessive Weight Gain in Adolescents (IPT-WG)

IPT has been adapted to prevent excessive weight gain (IPT-WG; Tanofsky-Kraff et al., 2007) in adolescents who report loss of control (LOC) in eating patterns and above-average body mass indices., LOC eating is common among youth, is associated with distress and high body-mass index (Tanofsky-Kraff, 2008), predicts excessive weight gain over time (Tanofsky-Kraff et al., 2009), and is a putative marker of risk for development of subsequent clinical eating pathology, such as binge eating disorder (BED). To address this challenge, IPT-WG uses both IPT-AST for the prevention of adolescent depression (Young, Mufson, & Davies, 2006) and group IPT for binge eating disorder (Wilfley et al., 2000). During the interpersonal inventory, a “closeness circle” (Mufson, Dorta, Moreau, & Weissman, 2004) identifies the patient’s significant relationships. IPT-WG maintains focus throughout on linking negative affect to LOC eating, times when individuals eat in response to cues other than hunger, and over-concern about shape and weight (Wilfley et al., 2000). Prior to entering the group, each patient individually discusses a timeline of personal eating and weight-related problems (M. Tanofsky-Kraff, personal communication, December 11, 2008). In a controlled pilot study, girls in IPT-WG were less likely to demonstrate increases in BMI than those in a standard health education group. Girls with baseline LOC eating receiving IPT-WG experienced significantly greater reductions in LOC episodes than those in the control group (Tanofsky-Kraff et al., 2010; Frank & Levenson, 2011, p. 112).

IPT for LOC Eating in African-American Girls in Rural Settings

In recent work toward another adaptation, Cassidy and colleagues held focus groups of adolescents, parents, and community leaders to develop a protocol for adolescent African American (AA) girls with LOC eating patterns who live in rural areas (2013). Data from these focus groups suggested modifications, such as acknowledgement and discussion of different beauty ideals and changes in interpersonal communication tools, acceptable to AA families might make the treatment more culturally relevant. Participants indicated that a behavioral component designed to teach healthy eating habits, and a support network with parents and other community members, would help facilitate lasting change. This adaptation remains untested.

Group IPT—IPT-G

Wilfley and colleagues (1998) first adapted IPT to a group format for bulimia. Describing the adaptation progress, they note the importance of determining the “active ingredients” of treatment and ensuring they work effectively in a group setting (Wilfley, Frank, Welch, Spurrell, & Rounsaville, 1998). One powerful component of group psychotherapy is the unique social scenario of being with diagnostically similar peers. For the focus in IPT on interpersonal communication, providing a safe environment for practicing interpersonal skills with people who understand your problems is an ideal therapeutic strategy. The authors recommend scheduling three individual sessions at the beginning, middle, and end of treatment so that therapist and patient stay focused on the progress of the patient-specific problem area. The therapist provides each group member with a written summary of individual goals, as well as a summary of each group session. Finally, the therapist works to make individual therapeutic techniques (such as communication analysis) interactive, to keep other group members consistently involved.

The session-by-session breakdown is essentially the same as IPT for individuals. The first two sessions focus on engagement in the group process. In the subsequent five sessions, the therapist points out resistance to therapeutic process as being influenced by eating disorder symptoms and attempts to normalize resistance as manifestations of problem areas caused by those symptoms. The last two sessions, often accompanied by notable symptom exacerbation as members face a new role transition, consist of a review of the skills acquired and reinforcement of patients’ progress.

Wilfley and colleagues compared group IPT to group CBT and a waitlist condition for 56 women with bulimia nervosa (1993). The authors interpret the significant reduction of binge eating behaviors in both active treatment groups, which was not found in the waitlist group, as supporting the role of both eating behavior and interpersonal factors in treating bulimia (Frank & Levenson, 2011, p. 102).

IPT-G for Binge-Eating Disorder (BED)

Using much the same rationale for the relevance of IPT to eating disorders, Wilfley studied a slightly modified version of IPT-G versus group CBT for binge-eating disorder (BED). They found group IPT and CBT equally efficacious, both after acute treatment and at one-year follow-up (Wilfley et al., 2002).

IPT-G for Posttraumatic Stress Disorder

Perhaps because trauma is so pervasive among patients presenting to IPT-oriented clinicians, the last decade has seen numerous adaptations of both individual and group IPT for individuals with trauma histories. Researchers in Australia described an adaptation of group IPT for PTSD (Robertson, Rushton, Bartrum, et al., 2004). The program comprised ten 90- to 120-minute sessions. One or two therapists met with groups of four to eight patients who had experienced trauma in adult life. In a small open study, investigators found moderate improvement in some PTSD symptoms, as well as psychological distress and depressive symptoms among those who completed the treatment (Robertson et al., 2007).

Krupnick and colleagues (2008) reported on an RCT using an adaptation of group IPT for low-income women with PTSD in public health clinics compared to a waitlist control. The group was structured to accommodate patient needs by providing transportation and childcare. Participants receiving IPT-G showed significantly greater decreases in PTSD and MDD symptoms than the waitlist control group, whose participants were more than twice as likely to meet criteria for PTSD at termination (Krupnick et al., 2008). Addressing the social isolation commonly found among people with PTSD, the group format provides a beneficial opportunity for opportunities to practice IPT techniques in vivo.

IPT-G for Prisoners with Depressed and Substance use Disorder

IPT is pertinent to the treatment of incarcerated women with cooccurring depressive disorder (DD) and substance use disorder (SUD) because of their many interpersonal needs. Incarcerated women with DD-SUD face multiple interpersonal difficulties (SAMHSA, 1999; U.S. Department of Justice, 1999), and harmful attachments (Holtfreter & Morash, 2003). Johnson and Zlotnick (2008; 2012) conducted an RCT (following an open trial) using IPT-G based on a manual adapted from Wilfley et al. (2000) to address specific treatment needs of women prisoners, particularly seeking to improve social support both outside and inside prison. Both active and control conditions received abstinenceoriented SUD treatment for 16-30 hours per week in addition to IPT-G. Their primary modification of IPT-G is the timing of the sessions. Because many women serve short sentences (a few months), the treatment schedule was condensed. Women in the groups attended an individual pre-group, mid-group, and post-group session, as Wilfley recommends. The 24 group sessions occurred three times weekly for 8 weeks just prior to women’s release. As women often return to conflictual and high-risk interpersonal environments, the women also had individual sessions once weekly for 6 weeks after release.

The IPT theory of change itself appears to naturally fit issues common to women in this population. They spontaneously reported that the personalized, written case formulations linking depressive symptoms to the IPT problem areas helped in organizing their DD-SUD experiences and therapeutic efforts (Johnson & Zlotnick, 2008). Another modification expanded the “interpersonal deficits” problem area to include chronic, repeated attachment to abusive or exploitative relationships in addition to isolation, as this was commonly reported among women in this population (Johnson & Zlotnick, 2012). The researchers worked hard to help women address conflicts within the group. For most of the groups, these conflictual moments provided powerful in vivo experiences for learning communications skills, conflict resolution, and ultimately trust (J. Johnson, personal communication, December 12, 2008). In the open study and randomized controlled trial of this adaptation, approximately 70% of the women showed a significant decrease in depressive severity (Johnson & Zlotnick 2008; 2012).

Johnson and colleagues are currently conducting the first large-scale RCT to study treatment effectiveness and implementation of IPT-G for incarcerated men and women. The trial uses clinicians with bachelor’s degrees because clinicians with master’s-level degrees are rare in a prison setting (J. Johnson, personal communication, 22 November 2013; Frank & Levenson, 2011, p. 115-116).

IPT-G for Postpartum Depression

Many women suffering from postpartum depression isolate themselves from much-needed social support at a time when they need it most (Stuart, 2012). Group IPT is well suited to treat interpersonal issues and to normalize the experience with other women. Klier and colleagues have successfully used group IPT for postpartum depression, further increasing interpersonal contact by providing women with the phone numbers of the other group members. An uncontrolled pilot study demonstrated significant reduction in depressive symptoms (Klier, Muzik, Rosenblum, & Lenz, 2001).

Zlotnick and colleagues developed a preventive group treatment for pregnant women at risk for postpartum depression (Zlotnick, Miller, Pearlstein, Howard, & Sweeney, 2006). The shortened protocol consisted of four prenatal group sessions and one individual postpartum booster session to reinforce skills and address any current or anticipated interpersonal difficulties. In an RCT comparing this treatment to standard prenatal care, women in the active treatment group were significantly less likely to receive a diagnosis of postpartum depression at 3-month follow-up (Zlotnick et al., 2006).

IPT-G for Women Following Perinatal Loss

For women suffering from perinatal loss, the main modification of IPT addressed the problem area of grief. Women in this position need help dealing with feelings of fault and inadequacy, as well as strategies for responding to the reactions of others. Incorporating the patient’s significant other is important to reconcile distinct viewpoints and understand each other’s grief. An innovative change in the typical group format is entering new women into the group every four weeks. This strategy has two beneficial effects: to give existing group members a sense of their progress, and to allow new members to see other women who have progressed and receive the benefit of their experience (J. Johnson, personal communication, 22 November 2013).

IPT-G for Late-Life Depression

Scocco and colleagues (2002) adapted group IPT for late-life depression. Scocco notes that when choosing a problem area for the group, it is important to pick a potentially malleable one to avoid the hopeless feelings that often characterize late-life depression (Scocco, de Leo, & Frank, 2002). As therapists are often younger than patients in the group, one benefit of group treatment is for patients to see examples of other relatable, credible models for dealing with their particular problems.

IPT-G for Individuals with Depression in Rural Uganda

Verdeli and colleagues (2003) described group IPT for depressed individuals in rural Uganda. This population is suited for such treatment based on the epidemic regional prevalence of HIV, the high rate of depressive symptoms reported by those affected and their family members (often as a consequence of AIDS in their relatives), and limited treatment options due to the dearth of doctors and the prohibitive cost of medication. This modification maintains the original IPT structure but simplifies it for use by non-clinicians, and it increases the format’s flexibility to accommodate community lifestyle differences. To examine the feasibility of implementing this treatment in a rural African setting and to measure the efficacy of IPT for this population, the investigators grouped depressed participants by village into 15 groups of men and 15 groups of women, half of which were assigned to the IPT condition. Treatment groups were led by local individuals of the same sex as the group. These individuals had learned to conduct IPT during a 2-week intensive training course, providing evidence that local individuals could successfully train to effectively lead IPT-GU (Bolton et al., 2003). Those receiving IPT demonstrated a greater reduction in depressive symptoms, overall symptom severity, likelihood of a depression diagnosis at the end of treatment, and participants’ level of dysfunction than in those receiving TAU (Frank & Levenson, 2011, p. 17).

Brief Interpersonal Psychotherapy (IPT-B)

Swartz and colleagues (2004) saw a need to be able to offer an IPT-based treatment for depression to individuals unable to commit to 12 to 16 weekly psychotherapy sessions. The multiple uses this adaptation has already received and the further adaptations that have already been made are described in detail in this issue (pp. XXX to YYY). Briefly, this eight-session adaptation of IPT is intended for delivery by a mental health clinician (physician, psychologist, nurse, or social worker) specifically trained in IPT and IPT-B. In several of the initial IPT-B studies, a single-session engagement session preceded the treatment (Swartz et al., 2008; Zuckoff, Swartz, & Grote, 2008). Other modifications include a brief, more constrained, interpersonal inventory focused on current relationships. This is coupled with an effort to define and begin work on the selected the problem area by the third session. The problem area selected should be amenable to noticeable change within the brief arc of treatment. The therapist encourages the patient to take an even more active role than in classical IPT, and typically assigns specific “homework” tasks to facilitate rapid interpersonal and social role change. Termination is telescoped into a single session in which the decision is made whether to fully terminate or provide additional therapy.

In addition to the IPT-B adaptations Swartz and colleagues describe in this issue, our survey of the ISIPT listserve indicated other creative adaptations in development. Ravitz reported a telephone-based adaptation with Dennis and colleagues for women with postpartum depression (Dennis et al., 2012). Because new mothers with PPD have difficulties attending a treatment clinic and their attrition rates are high, the telephone is a promising way to overcome some of these barriers. No data have been published from this adaptation.

Whight described two adaptations she and her colleagues in the United Kingdom have studied for bulimic spectrum disorders. Interpersonal psychotherapy for Bulimia Nervosa - Modified (IPT-BNm), based on Fairburn’s model of treatment (1991), adds back treatment components (psychoeducation, food diaries, behavioral change techniques) that had been removed in studies comparing IPT to CBT (Arcelus et al., 2009). They developed a briefer version (IPT-BN10) after discovering that most symptom change occurs by session eight (Arcelus, Whight, Brewin, & McGrain, 2012). Both treatments significantly reduced the severity of both eating disorder and depressive symptoms.

The IPT In-Laws: Hybrid Treatments

Interpersonal and Social Rhythm Therapy (IPSRT)

Our research group has developed Interpersonal and Social Rhythm Therapy (IPSRT) as a modification of IPT for treating bipolar disorders (Frank, 2005). Initially developed for the individual treatment of adults with bipolar I disorder, IPSRT has been further adapted to the individual and group treatment of adults and adolescents across the full spectrum of bipolar disorders, including adolescents at risk for bipolar disorder by virtue of having a first degree relative with the illness.

As its main modification, IPSRT adds a social rhythm stabilizing component to address the disruption in sleep/wake and circadian rhythms characteristic of bipolar disorders, which may contribute to developing depressive and manic episodes. Beyond the typical focus on difficulties in interpersonal relationships, the therapist and patient work together to develop a plan for regulating daily activities, sleep patterns, and managing medications. Critical to this component is completion of the Social Rhythm Metric (SRM-II-5), a homework sheet that monitors the regularity of typical daily routines, which therapist and patient discuss in session (Frank, 2005). Because bipolar disorder is lifelong, and frequently complicates achieving life goals, IPSRT adds a fifth problem area—“grief for the lost healthy self.” Individual IPSRT for adults with bipolar disorders has been demonstrated an efficacious adjunct to pharmacotherapy both for treating bipolar depression (Miklowitz et al., 2007) and for preventing manic and depressive episodes (Frank et al, 2005).

Group Interpersonal and Social Rhythm Therapy (IPSRT-G)

To maximally implement IPSRT in an outpatient setting, Swartz and colleagues developed a group version (Swartz et al., 2011). To adequately address both the social rhythm stabilization and IPT components of treatment, the two were temporally sequenced over 12 to 16 weekly 90-minute sessions. A pilot study of this adaptation showed a significant decrease in depressive symptoms after 60 days, suggesting that the group format may work.

Interpersonal and Social Rhythm Therapy for Adolescents (IPSRT-A)

Irregular sleep schedules often adversely affect even healthy adolescents, making the stabilization of social rhythms salient to adolescents with bipolar disorder. To adapt IPSRT for adolescents with bipolar disorder, Hlastala and colleagues (2010) based many modifications on Mufson’s work on IPT-A (Mufson, Moreau, Weissman, Wickramaratne, Martin, & Samoilov, 1994). They adapted the SRM for this age group and added interventions targeting school-functioning. Parents and other family members participated in two to three psychoeducational sessions to bolster treatment gains at home. An open trial found the intervention feasible (97% attendance rate) and efficacious, demonstrating large improvements in general psychiatric symptomatology, mania, and functioning as well as a medium-to-large improvement in depression (Hlastala, Kotler, McClellan, & McCauley, 2010). IPSRT appears to be a promising treatment for adolescent bipolar spectrum disorders.

Preventive IPSRT for Adolescents At-Risk of Bipolar Disorder

Based on the apparent promise of IPSRT-A for adolescents already diagnosed with bipolar disorder (Hlastala & Frank, 2006), researchers from the University of Pittsburgh and the University of Washington have begun a trial investigating the effect of IPSRT-A as a preventive treatment for at-risk adolescents [(Goldstein et al., 2014). The study rationale is based on numerous studies indicating that poor sleep and social rhythm regulation, particularly during periods of stress, are associated with the onset of mania and depression in vulnerable individuals. Because adolescence is characterized by significant alterations in social routines and sleep/wake patterns, and is a key developmental stage for illness onset, this period may prove an optimal time for a preventive intervention targeting stabilization of social rhythms for high-risk teens.

The single most potent risk factor for developing bipolar disorder is a positive family history of the illness. Therefore, we (Goldstein, Frank, Axelson, and Birmaher [Pittsburgh] and Hlastala [Washington]) conducted an open pilot treatment development trial examining an adaptation of IPSRT (Goldstein et al., 2014) as a preventive intervention for adolescents at high risk for bipolar disorder by virtue of a first-degree relative with the illness. Treatment modifications are designed to target the unique needs of an at-risk population and include abbreviated treatment length and incorporation of motivational strategies. Data are being collected to assess change in symptoms, sleep, energy, and psychosocial functioning. The intervention appears feasible and early cases suggest that IPSRT treatment that focuses on stabilizing daily rhythms and interpersonal relationships may benefit at-risk adolescents (Goldstein et al., 2014).

Other Hybrid IPT Treatments

Sober Network IPT for Women Leaving Prison with Substance use Problems and Major Depression

Johnson and colleagues have adapted IPT as a transitional intervention for women leaving prison who have substance use problems and major depression (SUD+MDD) by implementing treatment over the telephone (J. Johnson, personal communication, 22 November, 2013). Women leaving prison find this transition difficult to manage sober and often relapse immediately post-release. Known as Sober Network IPT, this “in-law” adaptation integrates 12-step treatments with IPT to better address the SUD by creating a “sober network.” Bachelor’s-degree level substance use counselors implemented treatment, calling participants daily to check in. This modification was crucial, as most relapse occurs immediately following release from prison. A feasibility trial showed significant reductions in depression and substance abuse from baseline (in prison) to the end of the study (3 months post-release) (Johnson, Williams, & Zlotnick, in press).

Sober Network IPT for Perinatal Women with Substance use Disorder and Major Depression

The same group adapted this Sober Network IPT approach without the phones for outpatient perinatal women with SUD+MDD. Considering the strongly deleterious effects of substance use and depression for both mother and baby, an effective treatment for this group is crucial from a public health standpoint. An RCT is underway (personal communication J. Johnson, 22 November, 2013).

IPT with CBT Techniques for Body Dysmorphic Disorder (BDD)

Body Dysmorphic Disorder (BDD) is a preoccupation with an imagined or slight defect in appearance that causes clinically significant distress or impairment in social, occupational, or other important areas of functioning. A manualized pilot trial explored IPT-BDD with a 19-session duration. Specific modifications focus on the association of BDD with various interpersonal deficits, including: 1) making connections between appearance concerns and social problems and exploring specific suggestions for decreasing social avoidance; 2) focusing on the therapeutic relationship; and 3) integrating selected, highly compatible CBT techniques with IPT. Borrowing from the IPT modification for dysthymia (Markowitz, 1998), the therapist may focus on a therapeutic transition (e.g., from the sick role to a healthier, more adaptive role) that involves the patient learning new skills to accompany a more assertive and less avoidant approach to others. The area of grief/loss has been broadened to incorporate work on the “loss of the healthy self” (Frank, 2005) and “loss of body perfection.” (E. Didie, personal communication, December 18, 2008; Frank & Levenson, 2011, p. 117–118).

IPT with CBT Techniques for Depression with Panic Symptoms

Beginning in the late 1990s, several studies indicated that depressed patients with comorbid anxiety fared more poorly than those without such comorbidity. (Brown, Schulberg, Madonia, Shear, & Houck, 1996; Feske, Frank, Kupfer, Shear, & Weaver, 1998; Frank et al., 2000). This led Cyranowski et al. (2005) to design a pilot study to test an adaptation of IPT for depression complicated by panic symptoms (IPT-PS). This adaptation provided psychoeducation regarding anxiety symptoms, added some cognitive-behavioral strategies, which included targeting of avoidance behaviors. They also added behavioral strategies for addressing procrastination, and cognitive strategies for addressing separation fears. Although this pilot study lacked a control group, and patients who did not remit with IPT-PS were permitted pharmacotherapy, the results suggested substantial improvement in both depression and anxiety (Cyranowski et al., 2005). A full-scale comparative trial is yet to be conducted.

Why has IPT Been Selected as the Basis for so Many Adaptations?

Working on this report raised questions about why IPT has generated so much creative therapy development. One answer is that IPT’s apparently limited focus on four potential interpersonal problem areas is not a limited focus at all. Rather, the four IPT problems areas seem to encompass much of what produces psychological distress of all kinds, thus enabling creative therapists to understand the problems of their patients through a clear lens and to help patients work through unresolved grief, make successful transitions out of one life role into another, resolve painful disputes with important others, and understand some of the reasons why interpersonal relationships have not been more satisfying. IPT may provide just enough, but not too much, of a framework for therapeutic work. It provides therapists with useful strategies and tactics (communication analysis, role play, decision analysis, etc.), but is not prescriptive as to when or how they should be used.

Is IPT infinitely adaptable? Infinitely efficacious? Clearly not. There are some conditions where it has generally not worked well, such as in the treatment of substance abuse, chronic depression or anorexia. For other conditions, such as the prevention of recurrent depression, it has proven helpful, but less helpful than pharmacotherapy. To our knowledge no one has attempted to adapt IPT for OCD, schizophrenia, or other psychotic disorders. Indeed, it is difficult to imagine how one might apply the IPT problem areas to these disorders.

Nonetheless, IPT does appear to provide a firm footing on which to approach much of what troubles individuals seeking mental health treatment. Even diagnoses, such as bipolar disorder, which have a clear biological basis, occur in an interpersonal context. Helping individuals with such conditions resolve interpersonal and social role difficulties that perpetuate or are caused by their illness can greatly improve the quality of their lives.

(2009). A case series evaluation of a modified version of interpersonal psychotherapy (IPT) for the treatment of bulimic eating disorders: A pilot study. European Eating Disorders Review, 17, 260–268. doi:

(2012). A brief form of interpersonal psychotherapy for adult patients with bulimic disorders: A pilot study. European Eating Disorders Review, 20, 326–330. doi:

, (2007). Does interpersonal psychotherapy improve clinical care for adolescents with depression attending a rural child and adolescent mental health service? Study protocol for a cluster randomised feasibility trial. BMC Psychiatry, 7(53), 1–7.Medline, Google Scholar

(2007). Combined therapy of major depression with concomitant borderline personality disorder: comparison of interpersonal and cognitive psychotherapy. The Canadian Journal of Psychiatry, 52(11), 718–725.Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

(2005). A pilot study of interpersonal psychotherapy for posstraumatic stress disorder. The American Journal of Psychiatry, 162(1), 181–183.Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

, (2003). Group interpersonal psychotherapy for depression in rural Uganda: a randomized controlled trial. Journal of the American Medical Association, 289(13), 3117–3324.Crossref, Google Scholar

(2008). Residential cognitive therapy versus residential interpersonal therapy for social phobia: a randomized clinical trial. Journal of Anxiety Disorders, 22(6), 991–1010. doi:

(1996). Treatment outcomes for primary care patients with major depression and lifetime anxiety disorders. The American Journal of Psychiatry, 155(10), 1293–1300.Google Scholar

, (2004). Efficacy of disulfiram and cognitive behavior therapy in cocaine-dependent outpatients. Archives of General Psychiatry, 61, 264–272.Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

(1991). A comparative trial of psychotherapies for ambulatory cocaine abusers: relapse prevention and interpersonal psychotherapy. American Journal of Drug and Alcohol Abuse, 17(3), 229–247.Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

(2011). The long-term efficacy of three psychotherapies for anorexia nervosa: A randomized, controlled trial. International Journal of Eating Disorders, 44(7), 647–654. doi:

(2013). Adapting interpersonal psychotherapy for the prevention of excessive weight gain in rural African-American girls. Journal of Pediatric Psychology, 38(9), 965–977.Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

, (2005). Interpersonal psychotherapy for depression with panic spectrum symptoms: a pilot study. Depression and Anxiety, 21, 140–142.Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

, (2004). Personality pathology and outcome in recurrently depressed women over 2 years of maintenance interpersonal psychotherapy. Psychological Medicine, 34, 659–669.Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

(2001). A randomized controlled trial comparing moclobemide and moclobemide plus interpersonal therapy in the treatment of dysthymic disorder. The Journal of Psychotherapy Practice and Research, 10(2), 117–123.Medline, Google Scholar

(2012). The effect of telephone-based interpersonal psychotherapy for the treatment of postpartum depression: Study protocol for a randomized controlled trial. Trials, 13(38), doi:

(2008). Family-based interpersonal psychotherapy for depressed preadolescents: an open-treatment trial. Early Intervention in Psychiatry, 2, 180–187.Crossref, Google Scholar

, (1991). Three psychological treatments for bulimia nervosa. Archives of General Psychiatry, 48, 463–469.Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

(1998). Anxiety as a predictor of response to interpersonal psychotherapy for recurrent major depression: an exploratory investigation. Depression and Anxiety, 8, 135–141.Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

(2005). Treating Bipolar Disorder: A Clinician’s Guide to Interpersonal and Social Rhythm Therapy. New York: Guilford Press.Google Scholar

, (2000). Interpersonal psychotherapy and antidepressant medication: evaluation of sequential treatment strategy in women with recurrent major depression. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, 61, 51–57.Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

(1993).

, (1990). Three-year outcomes for maintenance therapies in recurrent depression. Archives of General Psychiatry, 47, 1093–1099.Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

, (2005). Two-year outcomes for interpersonal and social rhythm therapy in individuals with bipolar I disorder. Archives of General Psychiatry, 62(9), 996–1004.Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

Early intervention for adolescents at high risk for the development of bipolar disorder: Pilot study of Interpersonal and Social Rhythm Therapy (IPSRT). Psychotherapy, 51: 180–189, 2014.Google Scholar

(2006). Adapting Interpersonal and Social Rhythm Therapy to the developmental needs of adolescents with bipolar disorder. Development and Psychopathology, 18, 1267–1288.Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

(2010). Interpersonal and Social Rhythm Therapy for adolescents with bipolar disorder: treatment development and results from an open trial. Depression and Anxiety, 27(5), 457–464. doi:

(2003). The needs of women offenders: implications for correctional programming. Women and Criminal Justice, 14, 137–160.Crossref, Google Scholar

(2011). Effects of group interpersonal psychotherapy and group cognitive behavioral therapy on social anxiety in college students. Chinese Mental Health Journal, 25(5), 324–327. Retrieved from http://search.proquest.com/docview/910380018?accountid=14709Google Scholar

(2013). Integrating psychotherapy research with public health and public policy goals for incarcerated women and other vulnerable populations. Psychotherapy Research, 24(2) 229–239.Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

(2008). A pilot study of group interpersonal psychotherapy for depression in substance-abusing female prisoners. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment, 34, 371–377. doi:

(2012). Pilot study of treatment for major depression among women prisoners with substance use disorder. Journal of Psychiatric Research, 46(9), 1174–1183. doi:

(1987). Efficacy of a brief psychosocial intervention for symptoms of stress and distress among patients in primary care. Medical Care, 25(11), 1078–1088.Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

(1984). Interpersonal Psychotherapy of Depression: Basic Books.Google Scholar

(2001). Interpersonal psychotherapy adapted for the group setting in the treatment of postpartum depression. Journal of Psychotherapy Practice and Research, 10(2), 124–131.Medline, Google Scholar

(2004). An open-label trial of interpersonal psychotherapy in depressed patients with coronary disease. Psychosomatics, 45(4), 319–324.Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

(2008). Group interpersonal psychotherapy for low-income women with posttraumatic stress disorder. Psychotherapy Research, 18(5), 497–507. doi:

, (2007). Effect of citalopram and interpersonal psychotherapy on depression in patients with coronary artery disease: the Canadian Cardiac Randomized Evaluation of Antidepressant and Psychotherapy Efficacy (CREATE) trial. Journal of the American Medical Association, 297(4), 367–379.Crossref, Google Scholar

(2006). An open pilot study of interpersonal psychotherapy for panic disorder (IPT-PD). The Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease, 194(6), 440–445.Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

, (2008). A randomized trial of interpersonal therapy versus supportive therapy for social anxiety disorder. Depression and Anxiety, 25, 542–553.Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

(1997). Manual for interpersonal psychotherapy of social phobia. Unpublished Manuscript. Columbia University College of Physicians and Surgeons.Google Scholar

(1996). Psychotherapy for dysthymic disorder. Psychiatric Clinics of North America, 19, 133–149.Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

(1998). Interpersonal Psychotherapy for Dysthymic Disorder. Washington, D.C.: American Psychiatric Press.Google Scholar

(2007). Adapting interpersonal psychotherapy for borderline personality disorder. Journal of Mental Health, 16(1), 103–116. doi:

(1993).

(2005). A comparative trial of psychotherapy and pharmacotherapy for ‘pure’ dysthymic patients. Journal of Affective Disorders, 89, 167–175.Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

(2008). Pilot study of interpersonal psychotherapy versus supportive psychotherapy for dysthymic patients with secondary alcohol abuse or dependence. The Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease, 196(6), 468–474.Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

, (1998). Treatment of depressive symptoms in human immunodeficiency virus-positive patients. Archives of General Psychiatry, 55(5), 452–457.Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

(2006). Interpersonal psychotherapy for borderline personality disorder: possible mechanisms of change. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 62(4), 431–444.Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

(1993).

(2005). Three psychotherapies for anorexia nervosa: A randomized, controlled trial. The American Journal of Psychiatry, 162(4), 741–747. doi:

(2007). Psychosocial treatments for bipolar depression: a 1-year randomized trial from the systematic treatment enhancement program. Archives of General Psychiatry, 64, 419–427.Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

(2007). Expanding the usefulness of interpersonal psychotherapy (ipt) for depressed elders with co-morbid cognitive impairment. International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 22, 101–105. doi:

(1991). Interpersonal psychotherapy for adolescent depression: Description of modification and preliminary application. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 30(4), 642–651.Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

(2004). Interpersonal Psychotherapy for Depressed Adolescents (2nd ed.). New York: Guilford Press.Google Scholar

(2004). A randomized effectiveness trial of interpersonal psychotherapy for depressed adolescents. Archives of General Psychiatry, 61, 577–584.Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

(1996). Interpersonal psychotherapy for depressed adolescents: a one year naturalistic follow-up study. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry 35(9), 1145–1155.Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

(2004). A group adaptation of interpersonal psychotherapy for depressed adolescents. American Journal of Psychotherapy, 58(2), 220–237.Link, Google Scholar

(1993). Interpersonal Psychotherapy for Depressed Adolescents. New York: Guilford Press.Google Scholar

(1994). Modificatio of interpersonal psychotherapy with depressed adolescents (IPT-A): phase I and II studies. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 33(5), 695–705.Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

(1999). Efficacy of interpersonal psychotherapy for depressed adolescents. Archives of General Psychiatry, 56(6), 573–579.Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

(2007). Preliminary open trial of interpersonal counseling for subsyndromal depression following miscarriage. Depression and Anxiety, 24(3), 219–222. doi:

(2000). Efficacy of interpersonal psychotherapy for postpartum depression. Archives of General Psychiatry, 57, 1039–1045.Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

(1996). The Broken Mirror: Understanding and Treating Body Dysmorphic Disorder. New York: Oxford University Press.Google Scholar

(1997). Gender differences in body dysmorphic disorder. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease, 185(9), 570–577.Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

(2000). Personality disorders and traits in patients with body dysmorphic disorder. Comprehensive Psychiatry, 41(4), 229–236.Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

(1995). Body dysmorphic disorder: an obsessive compulsive spectrum disorder, a form of affective spectrum disorder, or both? Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, 56(S), 41–52.Medline, Google Scholar

(1993). Body dysmorphic disorder: 30 cases of imagined ugliness. The American Journal of Psychiatry, 150(2), 302–308.Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

(1996). Prevalence and clinical features of body dysmorphic disorder in atypical major depression. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease, 184, 125–129.Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

(2004). Self-esteem in body dysmorphic disorder. Body Image: An International Journal of Research, 1, 385–390.Crossref, Google Scholar

(2008). Telephone-delivered, interpersonal psychotherapy for HIV-infected rural persons with deprssion: A pilot trial. Psychiatric Services, 59(8), 871–877.Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

(2009). Patients’ depression treatment preferences and initiation, adherence, and outcome: A randomized primary care study. Psychiatric Services, 60(3), 337–43. Retrieved from http://search.proquest.com/docview/213090955?accountid=14709Google Scholar

(2011, November).

(2006). Maintenance treatment of major depression in old age. The New England Journal of Medicine, 354(11), 1130–1138. doi:

, (1999). Nortriptyline and interpersonal psychotherapy as maintenance therapies for recurrent major depression. The Journal of American Medical Association, 281(1), 139–145.Google Scholar

(2007). Open trial of interpersonal psychotherapy for chronic post traumatic stress disorder. Australian Psychiatry, 15(5), 375–379.Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

(2004). Group-based interpersonal psychotherapy for posttraumatic stress disorder: theoretical and clinical aspects. International Journal of Group Psychotherapy, 54(2), 145–175.Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

(1985). Interpersonal psychotherapy adapted for ambulatory cocaine abusers. American Journal of Drug and Alcohol Abuse, 11(3–4), 171–191.Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

(1983). Short-term interpersonal psychotherapy in methadone-maintained opiate addicts. Archives of General Psychiatry, 40(6), 629–636.Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

(1993).

(2002). Is interpersonal psychotherapy in group format a therapeutic option in late-life depression?. Clinical Psychology and Psychotherapy, 9, 68–75. doi:

(2012). Therapist adherence to interpersonal vs. supportive therapy for social anxiety disorder. Psychotherapy Research, 22(4), 381–388. doi:

(1997). Interpersonal psychotherapy for depressed antepartum women: A pilot study. The American Journal of Psychiatry, 154(7), 1028–1030. Retrieved from http://search.proquest.com/docview/619113038?accountid=14709Google Scholar

(2003). Controlled clinical trial of interpersonal psychotherapy versus parenting education program for depressed pregnant women. The American Journal of Psychiatry, 160, 555–562.Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

(2013).

(2011). Cognitive therapy vs interpersonal psychotherapy in social anxiety disorder: A randomized controlled trial.. Archives of General Psychiatry, 68(7), 692–700. doi:

(2012). Interpersonal psychotherapy for postpartum depression. Clinical Psychology and Psychotherapy, 19, 134–140. doi:

(1995). Interpersonal psychotherapy for postpartum depression: a treatment program. The Journal of Psychotherapy Practice and Research, 4, 18–29.Medline, Google Scholar

(2011). Implementing interpersonal and social rhythm therapy for mood disorders across a continuum of care. Psychiatric Services, 62(11), 1377–80. Retrieved from http://search.proquest.com/docview/1318500720?accountid=14709Google Scholar

(2004). Brief interpersonal psychotherapy for depression in women: A pilot study. Psychiatric Services, 55, 448–453.Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

(2008). Brief interpersonal psychotherapy for depressed mothers whose children are receiving psychiatric treatment. The American Journal of Psychiatry, 165(9), 1155–1162. doi:

, (2005). Interpersonal Psychotherapy for depressed women with sexual abuse histories: a pilot study in a community mental health center. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease, 193, 847–850.Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

(2011). A randomized effectiveness trial of interpersonal psychotherapy for depressed women with sexual abuse histories. Psychiatric Services, 62(4), 374–380.Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar