Three Cases of Dissociative Identity Disorder and Co-Occurring Borderline Personality Disorder Treated with Dynamic Deconstructive Psychotherapy

Abstract

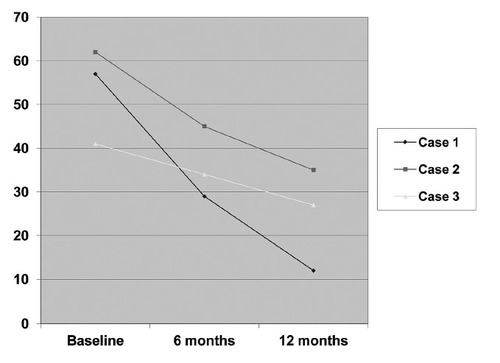

Dissociative Identity Disorder (DID) is an under-researched entity and there are no clinical trials employing manual-based therapies and validated outcome measures. There is evidence that borderline personality disorder (BPD) commonly co-occurs with DID and can worsen its course. The authors report three cases of DID with co-occurring BPD that we successfully treated with a manual-based treatment, Dynamic Deconstructive Psychotherapy (DDP). Each of the three clients achieved a 34% to 79% reduction in their Dissociative Experiences Scale scores within 12 months of initiating therapy. Dynamic Deconstructive Psychotherapy was developed for treatment refractory BPD and differs in some respects from expert consensus treatment of DID. It may be a promising modality for DID complicated by co-occurring BPD.

Introduction

Dissociative Identity Disorder (DID) is a relatively common disorder, especially in clinical populations. Johnson and colleagues found the prevalence to be 1.5% in a population of 658 adults in a community-based longitudinal study (Johnson, Cohen, Kasen, & Brook, 2006). Foote and colleagues (2006) noted the prevalence of DID to be 6% in a study of inner city, psychiatric outpatients. Among adult psychiatric inpatients, estimates of prevalence have varied from 0.9 to 5% (Gast, Rodewald, Nickel, & Emrich, 2001; Rifkin, Ghisalbert, Dimatou, Jin, & Sethi, 1998; Ross, 1991).

Figure 1. DISSOCIATIVE EXPERIENCES SCALE SCORES OF 3 PATIENTS WITH DISSOCIATIVE IDENTITY DISORDER

The conceptualization and treatment of DID has been rife with controversy, reflecting in part a dearth of empirical research. A PsychINFO search using the terms dissociative identity disorder and clinical trials indicated no published randomized controlled trials. Various treatment models have been applied to clients with DID, including psychodynamic psychotherapy, cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT), hypnosis, group therapy and family therapy. However, there is little empirical support for any model. In 1986, Putnam and colleagues published the results of a questionnaire given to 92 clinicians treating 100 cases of DID. Thirty six percent of the therapists asked to speak with specific alters, 32% awaited for alters to announce themselves, and 20% used hypnosis to elicit alters. Employing a survey of clinicians treating 305 clients with DID, Putnam and Lowenstein (1993) reported that individual therapy with hypnosis was the most common form of treatment. The average client was seen twice a week for an average of 3.8 years.

Many therapists utilize techniques that include speaking directly with the different alters. (Caul, 1984; Congdon, Hain, & Stevenson, 1961; Fine, 1991; Kluft, 1987; Putnam, 1989; Ross et al., 1990; Ross and Gahan, 1988). Other therapists warn against attending to alters (Gruenewald, 1971; Horton & Miller, 1972). There is concern that any acknowledgement of alters can result in “mutual shaping” of present or additional personalities. (Greaves, 1980; Spanos, 1985; Sutcliffe & Jones, 1962; Taylor and Martin, 1944).

Although hypnosis is a commonly used modality, evidence supporting its use is based primarily on case reports and a single case series (Coons, 1986). When using hypnosis, the therapist attempts to uncover and resolve traumatic experiences linked to specific alters. Coons (1986) reported on the outcomes of 20 clients treated with hypnosis and psychodynamic therapy. Based on global impressions by the treating clinicians, 5 of 20 clients with DID were reported to have “complete integration” over a 3-year period of treatment.

Another approach with preliminary empirical support is cognitive analytic therapy (CAT). In CAT practice, descriptions of dysfunctional relationship patterns and of transitions between them are worked out by therapist and client at the start of therapy and are used by both throughout its course (Ryle & Fawkes, 2007). Employing a single-case experimental design, Kellet (2005) utilized the dissociative experiences scale (DES) to measure the effectiveness of CAT during 16 months with one client. The client received the standard CAT design of 24 sessions with four follow-up sessions. The client developed insight, had reduced fragmentation, and improved self-manageability, but did not establish integration.

The model with the largest empirical basis has been Kluft’s (1999) individualized and multi-staged treatment. It involves making contact and agreement among alters to work towards integration, accessing and processing trauma with occasional use of hypnosis, learning new coping skills, and eventually fusion among the alters and the self. Using this model, Kluft (1984) describes treatment of 123 DID clients over a decade of observation. Of the clients, 83 (67%) achieved fusion, including 25 who sustained fusion over at least a 2-year-follow-up period without any residual or recurrent dissociative symptoms. Kluft noted that individuals with borderline personality traits were less likely to achieve stable fusion. A major limitation of his study was the lack of valid outcome measures or formalized assessment of adherence to the treatment protocol.

Dissociative symptoms commonly co-occur with borderline personality disorder (BPD) and the prevalence of DID among outpatients with borderline personality disorder (BPD) was 24% in two separate studies that employed structured diagnostic interviews (Korzekwa, Dell, Links, Thabane, & Fougere, 2009; Sar et al., 2003). Two treatment models targeting borderline personality disorder have been shown to be effective for reducing dissociative phenomena in randomized controlled trials. Koons and colleagues (2001) randomized 20 female clients who had BPD to either dialectical behavior therapy (DBT) or to treatment as usual. At 6 months, participants receiving DBT had a greater reduction in DES scores than those receiving usual care. However, in a shorter 12-week randomized controlled trial, 20 participants receiving DBT demonstrated no improvement in DES scores (Simpson et al., 2004).

The other treatment modality shown effective for dissociative phenomena with BPD is dynamic deconstructive psychotherapy (DDP). Gregory and colleagues (2008) randomized 30 participants with borderline personality disorder and co-occurring alcohol use disorders to either DDP or to optimized community care. Over 12 months of treatment, DES scores were significantly reduced among those receiving DDP, but not among those receiving optimized community care.

Although DBT and DDP have shown promise in reducing dissociative symptoms among clients with BPD, it is unclear whether they would be effective in treating DID. To our knowledge there are no reported cases of any treatment modality for DID complicated by co-occurring BPD employing validated, quantifiable outcome measures. The present observational study attempts to fill that gap in the literature by describing three cases of co-occurring DID and BPD treated with 12 months of DDP, using the DES as an outcome measure.

Methods

Participants

Participants include three consecutive cases of DID who had been provided treatment with DDP. All of them were young adult women who had been diagnosed with co-occurring BPD. They were administered the Dissociative Experiences Scale (DES; Bernstein & Putnam, 1986) at baseline, 6 months, and 12 months into treatment with DDP. The DSM-IV diagnoses of DID and BPD were assigned clinically in each case by the treating therapist. Identifying information has been removed or modified within the case reports to protect the privacy of the participants.

Measures

Dissociative Experience Scale

The DES is a 28-item self-report measure assessing a wide array of dissociative phenomena, and it has become the most commonly used and extensively researched scale for measuring the severity of dissociation. Internal consistency has ranged from .83 to .93 and test-retest reliability from .79 to .96 for 4-to-8 week periods (Carlson et al., 1993). There are no differences in scores associated with gender, race, religion, education, and income.

Clients rate their endorsement to each item on a continuum from 0% to 100%, and the mean score is calculated across items. The average DES score in clients with DID has ranged from 41 to 58 across studies, as compared to a median score of 11 for adults without mental disorders (Bernstein & Putnam, 1986; Ross et al., 1990). Steinberg, Rounsaville, and Cicchetti (1991), comparing the DES to diagnosis from structured interviews, found a cutoff score of 15 to 20 yielded good sensitivity and specificity for DID, whereas Ross, Joshi, and Currie (1991) used a cutoff score of 30 in their epidemiological study.

Treatment Intervention

Dynamic Deconstructive Psychotherapy structure is manual based and time limited, involving weekly individual therapy sessions over 12 to 18 months. In a 12-month randomized controlled trial with 30-month follow up, DDP significantly improved interpersonal functioning and reduced self-harm, suicide attempts, alcohol and drug misuse, depression, and dissociation among clients with co-occurring BPD and alcohol use disorders (Gregory et al., 2008; Gregory, Delucia-Deranja, & Mogle, 2010). Adherence to DDP techniques correlate strongly with positive outcomes (r = .64), supporting the effectiveness and specificity of DDP interventions (Goldman & Gregory, 2009).

Dynamic Deconstructive Psychotherapy theory combines the translational neuroscience of emotion processing with object relations theory and deconstruction philosophy (Gregory & Remen, 2008). Through therapy, the individual attempts to remediate the connection between self and one’s experiences and to deconstruct attributions that interfere with authentic and fulfilling relationships.

The practice of DDP targets three purported neurocognitive functions: association, attribution, and alterity. Association is the ability to verbalize coherent narratives of interpersonal episodes, including identification and acknowledgement of specific emotions within each episode. Association techniques involve facilitating discussion of a recent interpersonal episode, helping the client to form a complete narrative sequence and to identify and label specific emotions within the episode.

Attribution is the ability to form complex and integrated attributions of self and others. Attributions of clients with BPD are often distorted and polarized, described in black and white terms (Gregory, 2007). Attribution techniques involve deconstructing distorted, polarized attributions by exploring alternative meanings and motives within narratives.

Alterity is the ability to form realistic and differentiated attributions of self and others. Included within this function are self-awareness, empathic capacity, mentalization, individuation, and self-other differentiation. Alterity techniques are experiential within the client-therapist relationship; they attempt to disrupt the client’s stereotyped expectations by providing acceptance or challenge at key times.

Within the DDP model, DID is conceived primarily as an adaptation to severe trauma and as an end point along a continuum with other dissociative phenomena. Dissociation provides a mechanism for diminishing the emotional impact of trauma by splitting off awareness of feelings, perceptions, and memories from consciousness. However, once dissociation becomes established as a coping mechanism, even minor stresses can trigger it.

Given that clients with DID are often highly hypnotizable and may, therefore, be very suggestible (Braun, 1984), the concern within DDP theory is that alters may become reified as they are individually named and characterized. A DDP therapist explicitly refrains from hypnosis and refrains from exploring the various alters or calling them by name; but insists on addressing the client by his/her legal name. These aspects of DDP differ from expert consensus treatment guidelines of DID, which emphasize negotiation and cooperation between alters, including the occasional use of hypnosis for calming and exploration (International Society for the Study of Trauma and Dissociation, 2011). Also unlike the consensus guidelines, DDP explicitly avoids work on early trauma until later stages of therapy given the difficulty clients with BPD have in adaptively processing intense emotional experiences (Ebner-Priemer et al., 2008) and instead emphasizes narration of recent interpersonal encounters.

The DDP therapist reframes alters as “different parts of you that need to be integrated” while not favoring one aspect of the self over another. This aspect of DDP is largely consistent with the expert consensus DID guidelines emphasizing awareness and resolution of conflict between competing identities, rather than suppressing or ignoring them (International Society for the Study of Trauma and Dissociation, 2011). DDP theory and technique are summarized by Gregory and Remen (2008) and within the training manual (at http://www.upstate.edu/ddp).

For the present study, the therapists included the founder of DDP (RG; cases 2 and 3) and a senior psychiatry resident (SC; case 1). Training for the senior resident involved several didactic sessions in DDP, reading the training manual, and ongoing weekly case supervision by the founder to ensure treatment fidelity.

Results

Case 1

Ms. A. was a 33-year-old Caucasian female with a history of chronic major depression, severe dissociation, and narcissistic and borderline personality disorders. She started DDP with a psychiatric resident trainee after several years of recurrent psychiatric admissions for depression, suicidal attempts, and self-mutilation. She would whip herself with chains and used torture devices with religious/medieval themes. She had twice required cardiac resuscitation after overdoses.

Ms. A. also described multiple dissociative symptoms that occurred on a frequent basis. These included flashbacks of traumatic experiences, psychogenic amnesia of important events, derealization, depersonalization, and lapses in time. In addition, the patient described having three separate alters, each having a different name, age, and characteristics. On admission her DES score was 57.

Ms. A. stated her childhood was saddened by her father leaving home when she was about 3 years old; she spent most of her childhood awaiting his return. She vividly recalls feeling alone and spending hours in a rocking in a chair staring at a wall.

Her mother remarried a man who sexually abused Ms. A.’s younger brother and older sister and physically abused Ms. A. When the children revealed the abuse to their mother, she sought counseling at their church, which recommended therapy and that he remain in the home. Ms. A. felt betrayed by her mother for allowing the terror in the home to continue. Ms. A. could not recall feeling loved by her mother, who was a nurse and busy portraying herself a caring individual for others.

Ms. A. did well in school despite having chronic dissociative symptoms, she described as “spacing out” and feeling detached from the world. She enjoyed writing, and she pursued her interest in literature.

Ms. A. became pregnant during her senior year of high school, married, and had a second child. She had difficulties recalling most of her married life, but remembered her husband as being demanding and unloving. Eventually, her husband left her for her best friend.

Initially Ms. A. took on raising the two children on her own, but she was unable to work or even to talk on the telephone due to anxiety. Because of her prolonged periods of dissociation, she was unable to provide adequate and safe care for her children; Child Protective Services eventually removed them from her custody. They went to live with their father in another state. Ms. A. lost contact with her children because they refused to communicate with her.

Ms. A. engaged well in treatment with DDP, attending weekly sessions and developing a therapeutic alliance over the first few months. Much of her early treatment focused on her relationship with her mother, with whom she was living. The predominant theme was, “Do I have a right to be angry?”

She was angry at her mother for her behaviors and attitudes; her mother sympathized with Ms. A.’s ex-husband, insisted that Ms. A. use bed sheets and clothing stained with blood from Ms. A.’s prior cutting episodes, and discouraged her from attending psychotherapy.

At 6 months of therapy, Ms. A. had developed a strongly positive and somewhat dependent transference with the therapist, and she was much better at identifying and articulating feelings of anger, guilt, and shame. She also felt much less need to punish herself, and self-mutilating episodes became less frequent and less severe. Her DES score had decreased from 57 at baseline to 29 at 6 months. However, during therapist vacations, feelings of abandonment would surface in Ms. A., and these sometimes resulted in an exacerbation of self-mutilation and/or severe depression needing hospitalization.

During the final 6 months of therapy, Ms. A. focused a great deal on the preset planned termination of treatment. Vacations and the pending termination were reminders of the limitations of the therapist as an all-caring idealized object. On the one hand, Ms. A. felt as if she had a more integrated self, and she was beginning to expand her functional capacity through the formation of friendships and returning to school part-time. On the other hand, she felt abandoned by the therapist, and this was accompanied with exacerbations of depression, as Ms. A. redirected the anger towards her therapist onto herself. Ms. A. expressed worries about the future and she devalued treatment and the therapist’s role. The therapist struggled to remain empathic with Ms. A.’s worries (without giving false reassurance) and to tolerate the devaluation without becoming defensive.

By the end of treatment, Ms. A. appeared to have a more balanced view of her treatment and of herself. She could express anger with less internal hatred. Depression and suicide ideation markedly improved and 12-month DES score was 12. At termination, she gave the therapist a drawing of a Celtic knot to symbolize the integration of her disconnected self. She was transferred to the care of another therapist; the exact nature of her treatment and course is unknown. However, a chance encounter with the DDP therapist 5 years later revealed that Ms. A. was generally doing well and participating in part-time college coursework.

Case 2

Ms. B. was a married Caucasian female in her 30s with a long history of severe psychopathology. She delineated five alters, each with a separate name, gender, and age. She was unable to control unexpectedly switching between alters. Ms. B. also described frequent disruptive and embarrassing time lapses. On two occasions, these lapses occurred while she was in the changing room of a Department store: she would become aware of her surroundings after the store had closed and locked its doors.

In addition to dissociative symptoms, the client met criteria for multiple Axis I and II disorders, including BPD, Bipolar I, alcohol and drug dependence, post traumatic stress disorder, obsessive compulsive disorder, and anorexia nervosa, bingeing/purging type. She had a history of six psychiatric hospitalizations beginning in her early twenties; she was treated for suicide attempts, manic episodes, and/or psychosis.

Over the course of her illness, Ms. B. had tried multiple classes of psychotropic medications none successes in treatment, but she has some improvement with mood stabilizers and antipsychotic medications. She had been treated for 5 years in twice-weekly supportive psychotherapy, which had involved a progressively pathological and regressive client-therapist relationship, including cuddling and playing with blocks on the floor. As the client regressed, she also became intrusively demanding of her therapist’s time, which eventually led to the therapist terminating treatment and subsequent deterioration in the client’s condition.

Ms. B. began to see demons in her house, and develop paranoid delusions necessitating psychiatric hospitalization. Following hospitalization, the client was referred for a trial of DDP. At that time, her DES score was 62. Initial sessions focused on establishing clear parameters of treatment, boundary limitations within the client-therapist relationship, and psycho-education regarding the importance of avoiding boundary violations. The client repeatedly brought up interactions with her prior therapist, including her feeling abandoned by the therapist. She was able to work through conflicts regarding agency, i.e. if she or her therapist was to blame for various incidents. As the client gradually worked through her issues she had with her prior therapist, the focus shifted to her marital relationship. Her husband was extremely physically and emotionally abusive. He had prostituted her to his friends and acquaintances. Episodes of physical abuse would be followed by increased psychiatric symptoms, including dissociation. The DDP therapist helped the client identify, label, and acknowledge her emotions in interactions with her husband, and to work through her conflict of agency in that relationship, i.e. whether or not she provoked him to attack her. As Ms. B. worked this through, she decided to terminate the relationship with her husband. She temporarily lived with her parents and eventually lived independently. There was a mourning process involving de-idealization of her husband and of her parents, who pressured her to return to her husband.

Her symptoms of Axis I disorders steadily improved during the course of treatment, despite diminishing dosages of antipsychotic and mood stabilizer medications. Her symptoms of dissociation also improved and her DES score decreased to 45 by 6 months of treatment and to 35 by 12 months. Ms. B. described time lapses as less frequent and of shorter duration, and she began to sense an increased ability to control them. Shifts in personality style became less frequent and pronounced, and Ms. B. no longer described herself as having independent personalities, but rather described “parts of herself” that emerged at different times. She also described herself as “waking up” and feeling “more whole.”

As termination approached, the last phase of weekly treatment was difficult and involved working through feelings of abandonment. After 18 months of weekly sessions, monthly maintenance treatment, which was primarily supportive in nature, was initiated. Despite discontinuing all medications against advice 6 months after termination of weekly DDP, Ms. B. displayed gradual improvement in symptoms at 8-year post-treatment, however, she continued monthly supportive psychotherapy sessions.

During the follow-up period, Ms. B. decided to pursue a professional degree while on social security disability, which supported her efforts through Vocational and Educational Services for Individuals with Disabilities. She successfully completed her courses, came off disability, and has worked full time for the last 3 years of her follow-up period in a responsible professional position.

Case 3

Ms. C. was a divorced African American woman in her 30s, having a history of alcohol and cocaine dependence. She had moved to the area to “get clean” and leave negative influences. She heard about the study for co-occurring BPD and alcohol use disorders (Gregory et al., 2008), and subsequently enrolled and was randomized to DDP.

Ms. C. described lifelong difficulties with sudden shifts in mood and personality combined with impulsive behaviors, including misuse of alcohol, cocaine, and cannabis. Significant dissociative symptoms included frequent episodes of derealization, feelings of spaciness, fugue episodes, and three distinct personalities, each with a specific name. One of her alters was called “Sunlight.” Sunlight had been the primary alter in Ms. C.’s life for the past few years. Sunlight enjoyed dominating and manipulating men as a drug dealer and prostitute. Unlike Ms. C., Sunlight felt no emotional pain and saw no need for treatment.

Ms. C. was diagnosed with cocaine, alcohol and cannabis dependence, DID, and BPD at evaluation. An 18-month course of DDP therapy was planned. Her initial DES score was 41. Throughout treatment, the therapist addressed the client by her legal name, and reframed the different personalities as different being parts of Ms. C. that were poorly integrated. The focus in early treatment was an exploration of a series of tumultuous relationships with boyfriends. These men had histories of imprisonment and tended to be manipulative or threatening. Her relational pattern was initially to idealize the men. This was followed by disappointment, anger, and fear. She would then engage in manipulating or controlling them. In therapy, the client was able to identify, label, and acknowledge conflicting feelings towards them and to describe a core conflict between her desire to be taken care of by a strong man versus her desire to be independent and in control.

By 6 months in treatment, dissociative episodes were much improved; DES score was 34. Ms. C. was maintaining abstinence and she was able to avoid harmful relationships with men. She began to develop female friendships for the first time in her life and to pursue educational courses leading up to a professional degree.

By 9 months, Ms. C. began to take responsibility for her life but was felt overwhelmed by responsibilities. She became less committed to treatment and recovery, and she began to have increased cravings for substances along with drug dreams. She would speak glowingly about times in the past when she felt in control and without emotional pain in the role of Sunlight. Much of the remaining 6 months of treatment involved bringing Ms. C.’s ambivalence about recovery to consciousness and helping her to mourn the loss of grandiose fantasies. Ms. C. also had to mourn the loss of the therapy relationship. She left treatment 3 months before the scheduled termination so that she “wouldn’t have to say goodbye.” As part of the BPD and alcohol use disorder study, Ms. C. met with the research assistant for follow-up 30 months after enrollment (Gregory et al., 2010). She remained abstinent during the follow-up period despite lack of further treatment, finished her course work for a professional degree, and had been working fulltime during the last 12 months of the follow-up period.

Discussion

The three cases of DID with co-occurring BPD appeared to respond well to time-limited treatment with DDP. Average DES scores decreased from 53 to 25 over 12 months, indicating an average reduction of 54%. Long-term follow-up for Cases 2 and 3 indicated further improvement in symptoms and function occurred after termination of weekly DDP treatment. These findings are consistent with a randomized controlled trial of DDP for disorders that demonstrated significant improvement in DES scores over time (individuals with BPD and alcohol use Gregory et al., 2008).

A theoretical principal of DDP is that individuals with BPD have deficits in association, which involves a dis-association between emotional experience and verbal symbolic capacity (Gregory & Remen, 2008). Individuals are often unable to verbally describe, label, and sequence specific emotional experiences. Association deficits are manifested by incoherent narratives of emotionally charged interpersonal episodes and there is difficulty identifying and appropriately expressing emotions within such episodes.

Dissociation has been linked in prior studies to aberrant processing of emotional experiences. Deficits in the ability to identify and express emotions (as assessed by the Toronto Alexithymia Scale [TAS]), have been noted in traumatized populations, and have been linked to dissociative symptoms, as measured by the DES (Frewen, Pain, Dozois, & Lanius, 2006; McLean, Toner, Jackson, Desrocher, & Stuckless, 2006). Clients with DID have been noted to have a slowed response time to negative emotions on the Flanker test (Dorahy, Middleton, & Irwin, 2005). In large, population-based studies (Elzinga, Bermond, & van Dyck, 2002; Maaranen et al., 2005; Sayar, Kose, Grabe, & Topbas, 2005), the TAS and DES scores have been correlated with one another even when dissociative symptoms are severe enough to be pathological (Grabe, Rainermann, Spitzer, Gansicke, & Freyberger, 2000; Maaranen et al., 2005).

Dynamic Deconstructive Psychotherapy specifically targets association deficits by helping clients to develop coherent narratives of recent interpersonal episodes and to identify, label, and acknowledge emotions within such episodes. Given that deficits in emotion processing have been linked to dissociative symptoms, targeting these deficits should theoretically be helpful for dissociation. This hypothesis was supported by recent research demonstrating a strong and statistically significant correlation (r = .79) between the use of association techniques, as assessed by independent raters, and improvement in DES scores (Goldman & Gregory, 2010). It is, therefore, likely that the use of association techniques was a critical component of treatment response among the reported three cases of DID.

Since DBT also targets association deficits through helping clients to identify emotions associated with maladaptive behaviors, it is perhaps not surprising that this modality has been shown to be helpful in reducing dissociative symptoms (Koons et al., 2001). Whether DBT can be helpful for DID per se, remains to be seen.

Limitations of the present case series include the observational nature of the study, exclusive reliance on clinical diagnoses, and restriction of the study sample to clients with co-occurring BPD. It is unclear whether DDP would be effective for DID clients who are free from this severe personality pathology. The small number of cases also limits the ability to generalize findings. Large controlled trials are needed to better evaluate the efficacy of DDP and other treatment modalities for individuals who suffer from DID.

Conclusions

Dissociative Identity Disorder is a common and under-researched disorder. Borderline Personality Disorders frequently co-occurs with DID and has been noted to worsen its course. DDP is a treatment modality previously found effective for dissociative symptoms of BPD. The active component of DDP for dissociative symptoms may be the use of association techniques, whereby verbal symbolic capacity is linked to emotional experiences within narratives. The three cases presented in this report suggest that DDP can be an effective treatment for clients suffering from DID complicated by co-occurring BPD.

(1986). Development, reliability, and validity of a dissociation scale. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease, 174, 727–35.Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

(1984). Uses of hypnosis with multiple personality. Psychiatric Annals, 14, 34–40.Crossref, Google Scholar

, (1993). Validity of the Dissociative Experiences Scale in screening for multiple personality disorder: a multicenter study. American Journal of Psychiatry, 150, 1030–6.Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

(1984). Group and videotapes techniques for multiple personality disorder. Psychiatric Annals, 14, 43–50.Crossref, Google Scholar

(1961). A case of multiple personality illustrating the transition from role-playing. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease, 132, 497–504.Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

(1986). Treatment progress in 20 patients with multiple personality disorder. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease, 174, 715–721.Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

(2005). The effect of emotional context on cognitive inhibition and attentional processing in dissociative identity disorder. Behaviour Research & Therapy, 43, 555–68.Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

(2008). Distress and affective dysregulation in patients with borderline personality disorder: a psychophysiological ambulatory monitoring study. Journal of Nervous & Mental Disease, 196, 314–320.Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

(2002). The relationship between dissociative proneness and alexithymia. Psychotherapy & Psychosomatics, 71, 104–11.Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

(1991). Psychoanalysis: the common ground. International Journal of Psychoanalysis, 72 (Pt 1), 166–7.Medline, Google Scholar

(2006).Prevalence of dissociative disorders in psychiatric outpatients. American Journal of Psychiatry, 163, 623–629.Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

(2006). Alexithymia in PTSD: Psychometric and FMRI studies. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences, 1071, 397–400.Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

(2001). Prevalence of dissociative disorders among psychiatric inpatients in a German university clinic. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease, 189, 249–257.Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

(2009). Preliminary relationships between adherence and outcome in dynamic deconstructive psychotherapy. Psychotherapy: Theory, Research, Practice, Training, 46, 480–485.Crossref, Google Scholar

(2010). Relationships between techniques and outcomes for borderline personality disorder. American Journal of Psychotherapy, 64, 359–371.Link, Google Scholar

(2000). The relationship between dimensions of alexithymia and dissociation. Psychotherapy & Psychosomatics, 69, 128–31.Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

(1980). Multiple personality: 155 years after Mary Reynolds. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease, 168, 577–596.Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

(2007). Borderline attributions. American Journal of Psychotherapy, 61, 131–147Link, Google Scholar

, (2008). A controlled trial of psychodynamic psychotherapy for co-occurring borderline personality disorder and alcohol-use disorder. Psychotherapy Theory, Research, Practice, Training, 45,28–41.Crossref, Google Scholar

(2010). Dynamic deconstructive psychotherapy versus optimized community care for borderline personality disorder co-occurring with alcohol use disorders: 30-month follow-up. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease, 198, 292–298.Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

(2008). A manual-based psychodynamic therapy for treatment-resistant borderline personality disorder. Psychotherapy Theory, Research, Practice, Training, 45, 15–27.Crossref, Google Scholar

(1971). Hypnotic techniques without hypnosis in the treatment of dual personality. A case report. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease, 153, 41–46.Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

(1972). The etiology of multiple personality. Comprehensive Psychiatry, 13, 151–159.Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

(2006).Dissociative disorders among adults in the community impaired functioning, and axis I and II comorbidity. Journal of Psychiatric Research, 40, 131–140.Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

(1999). An overview of the psychotherapy of dissociative identity disorder. American Journal of Psychotherapy, 53, 289–319.Link, Google Scholar

(1992). The use of hypnosis with dissociative disorders. Psychiatric Medicine, 10, 31–46.Medline, Google Scholar

(2006). Dealing with alters: a pragmatic clinical perspective. Psychiatric Clinics of North America, 29, 281–304.Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

(1984). Treatment of Multiple Personality disorder; A study of 33 cases. Psychiatric Clinics of North America, 7, 9–29.Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

(1987). The simulation and dissimulation of multiple personality disorder. American Journal of Clinical Hypnosis, 30, 104–118.Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

, (2001). Efficacy of dialectical behavior therapy in women veterans with borderline personality disorder. Behavior Therapy, 32,371–390.Crossref, Google Scholar

(2009). Journal of Trauma & Dissociation, 10, 346–367.Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

(2005). Factors associated with pathological dissociation in the general population. Australian & New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry, 39, 387–394.Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

(2006). The relationship between childhood sexual abuse, complex post-traumatic stress disorder and alexithymia in two outpatient samples: examination of women treated in community and institutional clinics. Journal of Child Sexual Abuse, 15, 1–17.Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

(1989). Diagnosis and treatments of multiple personality disorder. New York: Guildford Press.Google Scholar

(1986). The clinical phenomenology of multiple personality disorder: review of 100 recent cases. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, 47, 285–293.Medline, Google Scholar

(1993). Treatment of multiple personality disorder: a survey of current practices. American Journal of Psychiatry, 150, 1048–1052.Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

(1998).Dissociative identity disorder in psychiatric inpatients. American Journal of Psychiatry, 155, 844–845.Medline, Google Scholar

(1988). Techniques in the treatment of multiple personality disorder. American Journal of Psychotherapy, 42, 40–52.Link, Google Scholar

(1990). Structured interview data on 102 cases of multiple personality disorder from four centers. American Journal of Psychiatry, 147, 596–601.Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

(1991). Epidemiology of multiple personality disorder and dissociation. Psychiatric Clinics of North America, 14, 503–517.Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

(1990). Dissociative experiences in the general population. American Journal of Psychiatry, 147, 1547–1552.Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

(2007).Multiplicity of selves and others: cognitive analytic therapy. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 63, 165–174.Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

, (2003). The Axis-I dissociative disorder comorbidity of borderline personality disorder among psychiatric outpatients. Journal of Trauma & Dissociation, 4, 119–136.Crossref, Google Scholar

, (2004). Combined dialectical behavior therapy and fluoxetine in the treatment of borderline personality disorder. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, 65, 379–385.Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

(1989). Hypnosis, demonic possession and multiple personality: Strategic enactments and disavowals of responsibility for actions. In A. Ward (Ed.) Altered states of consciousness and mental health; a cross cultural perspective (pps. 96–125). Newbury Park, CA.Google Scholar

(1991). Detection of dissociative disorders in psychiatric patients by a screening instrument and a structured diagnostic interview. American Journal of Psychiatry, 148, 1050–1054.Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

(1962). Personal identity, multiple personality and hypnosis. International Journal of Clinical and Experimental Hypnosis, 10, 231–269.Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

(1944). Multiple personality. Journal of Abnormal and Social Psychology, 49, 135–151.Google Scholar