The Patient–Therapist Interaction and the Recognition of Affects during the Process of Psychodynamic Psychotherapy for Depression

Abstract

The perceptions of patients (n = 25) and their therapists about psychodynamic psychotherapy for depression were assessed during the first treatment year using 23 scales. Patients and therapists independently evaluated the impact of depression on the therapeutic experience of the patients. The estimations of the impact of depression by the patients and therapists were concordant in the majority of the subjects, reflecting mutual tuning and a working alliance. The roles of affects and frustrating subjects in the treatment relationship were evaluated as significantly different by the patients and the therapists. The results highlight the importance of working on the expression of affects in the psychotherapy of depression.

Introduction

The specific mode of action of the two available evidence-based treatments for depression, antidepressive medication and psychotherapy, are not fully known (Cipriani et al., 2009; Antonuccio, Danton, & DeNelsky, 1995). Recent studies that compared psychopharmacological treatment to psychotherapy with regard to action on brain function revealed that psychopharmacological and psychotherapeutic treatment have some similar and some different modes of action on brain activity of patients with depression (Nemeroff et al., 2003). Modern brain research shows that psychotherapy seems to have specific features not shared by the effects of psychopharmacological treatment (Martin et al., 2001; Nemeroff et al., 2003). Despite these interesting findings, the core clinical features that make psychotherapy effective in depression are unknown.

Depression is a widespread, debilitating illness with far-reaching personal and economic implications for individuals, their families, and society (Hirschfeld et al., 2000). Major depressive disorder is associated with significant psychosocial disability that often exceeds those noted in common medical illnesses ( Judd et al., 2000). The impact of depression extends beyond the core symptoms, such as depressed mood and loss of energy, and it affects quality of life, including the ability to function socially and to maintain and enjoy relationships and work (Hirschfeld et al., 2000). Feelings of disappointment, love, anger, criticism, neglect, or undermining destructiveness are turned inward, causing suffering or perceived victimhood. This can be seen in the depressed person’s ways of communicating, relating, and thinking.

Narcissistic vulnerability in depression triggers depressive affects, such as worthlessness and shame, resentment, and even rage in response to negative experiences (Busch, Rudden, & Shapiro, 2004). Anger leads to disruption and withdrawal in interpersonal relationships. This leads to a cycle of restricted interaction with social objects, an inability to grasp his or her behaviour, or in the total absence of the object of anger, a tendency to turn resentment toward the self, lowering of self-esteem. Guilt, fear of punishment and the devalued self-image further tax self-esteem and sensitize the individual to negative self-perceptions and criticism by others (Bush et al., 2004). Ineffective ability to deal with anger, and the concomitant painful affects of depression, increase the tendency to low mood through anger directed at the self or though a vision of the world as hostile, menacing, uncaring, or defeating (Bush et al., 2004). Also common are feelings of love and hate or ambivalence directed towards the same person (Morgan & Taylor, 2005). In the social sphere, current life stress and dysfunctional interpersonal relationships often accompany depression (Keller, Neale, & Kendler, 2007; Kendler, Kuhn, & Prescott, 2004; Kendler, Thornton, & Prescott, 2001; Luyten, Blatt, Van Houdenhove, & Corveleyn, 2006). In addition to negative affects and their psychological and social consequences, moderate or severe depression is connected to functional impairment of the personality and interference with social and/or occupational functioning (Karasu et al., 1996). Central to the psychodynamic approach with depressed patient is the establishment of the interpersonal meaning and context of their depression (Gabbard, 1994). Many of the same concerns that are problematic in the patient’s primary relationships will also surface in the transference (Gabbard, 1994).

In the psychotherapy process the patient is given an opportunity to develop a contact with the painful feelings and intentions prevalent in depression, which is as an important key to recovery (Taylor & Richardson, 2005). Getting in touch with the personal history of the patient and his/hers current life situation is likely to illuminate the origin of losses, traumata and conflicts behind the depression (Tähkä, 1993; Ursano, Sonnenberg, & Lazar, 1991).

To obtain treatment benefit the depressive patient must have an ability to work in a relationship absent serious regression or withdrawal. The promotion of affective self-expression has been found to be associated with improvement (Diener, Hilsenroth, & Weinberger, 2007), whereas affective blunting, typical for depression, can seriously hamper the development of a workable treatment relationship.

The therapeutic alliance appears to be a common relational factor across the different forms of psychotherapy of depression (Krupnick et al., 1996). However, the effect of the patient-therapist interaction is not a one-dimensional causal factor of the treatment, It functions as a context variable in the actuality of the bi-directional treatment relationship, in the psychosocial network of the patient, and as its history of the patient. Wampold (2001) has concluded, based on meta-analysis of outcome studies, that in psychotherapy, the impact of the setting and interaction have two main components: the working alliance and the “person” of the therapist.

Numerous studies have examined the relationship between the strength of the alliance and the outcome of the treatment (Safran, Muran, & Proskurov, 2008); however, thus far little attention has been paid to the core dynamics and manifestation of depression during the psychotherapy process. From a clinical point of view, it is likely that their influence, especially that of affective inhibition, has an effect on the therapy process.

In this study, our aim was to investigate to what extent the core elements of depression are evaluated similarly or differently by patients and therapists during the course of the psychodynamic psychotherapy process. Although several process scales for psychotherapy are available (Barret-Lennard, 1962; Murphy & Tyrer, 1992; Marziali, Marmar, & Krupnic, 1981; Stiles, 1980; Truax & Carchuff, 1967), to our knowledge no scale has been developed for psychodynamic psychotherapy in the treatment of depression.

This study focused on the first year of the psychotherapy process. We developed a process=description questionnaire aiming to study and describe the core dynamics and manifestations of depression during psychodynamic psychotherapy from the viewpoint of both patients and therapists. We compared evaluations of the therapy process by the patients and therapists using a questionnaire on treatment-related subjects, which was completed at different stages of therapy for major depression. We also examined the manifestation of depression in patients’ lives and the changes occurring in affective dynamics and life-management skills during the psychotherapy process.

Methods

Study Design and Participants

This study formed part of an investigation into the outcome of psychodynamic psychotherapy at the Department of Psychiatry of Kuopio University Hospital in Finland. The patients were referred by health care centres, the student health care organisation, and occupational health care services for an examination to participate in the study. The inclusion criteria were moderate or severe depression without psychotic symptoms. There was no limit for the length of the depression. The patients were drug naïve and had received no previous psychiatric treatment. Psychotic symptoms, bipolar disorder, substance abuse, severe personality disorders and somatic illnesses were exclusion criteria. All patients provided written informed consent. The study was approved by the ethical committee of Kuopio University Hospital.

Psychiatric Measures

Psychiatric diagnoses (Table 1) were based on clinical assessment and verified for all study subjects by a trained independent psychiatrist using the Structured Clinical Interviews for DSM-IV-R (SCID-1 and SCID-II; American Psychiatric Association [APA], 1994). The SCID-II was completed after 12 months of treatment. We used the 17-item Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression (HAM-D-17; Hamilton, 1960) and the Montgomery-Åsberg Depression Rating Scale (MADRS; Montgomery & Åsberg, 1978) to measure the severity of symptoms. Ratings were completed by a trained, independent psychiatrist. Clinical and laboratory examinations, as well as MRI imaging, were performed to exclude somatic disorders and focal brain abnormalities and for further research purposes, based on our previous findings of the biological variables of the study subjects (Joensuu et al., 2006; Lehto et al., 2007, 2008).

| Sex | Age | Dg | ||

| Male/Female | Years | DSM-IV-R Axis-I | DSM-IV-R Axis-II | |

| Pt 1 | f | 34 | 296.32 Major Depressive Disorder, Recurrent, Moderate | |

| Pt 2 | f | 28 | 296.23 Major Depressive Disorder, Single Episode, Severe | 301.4 Obsessive-Compulsive Personality Disorder 301.0 Paranoid Personality Disorder 301.83 Borderline Personality Disorder |

| Pt 3 | f | 20 | 296.22 Major Depressive Disorder, Single Episode, Moderate 300.40 Dysthymic Disorder | |

| Pt 4 | m | 25 | 296.32 Major Depressive Disorder, Recurrent, Moderate | |

| Pt 5 | f | 28 | 296.32 Major Depressive Disorder, Recurrent, Moderate 300.40 Dysthymic Disorder | 301.0 Paranoid Personality Disorder |

| Pt 6 | f | 20 | 296.22 Major Depressive Disorder, Single Episode, Moderate 300.40 Dysthymic Disorder | 301.9 Personality Disorder NOS |

| Pt 7 | f | 24 | 296.22 Major Depressive Disorder, Single Episode, Moderate | |

| Pt 8 | f | 33 | 296.22 Major Depressive Disorder, Single Episode, Moderate | |

| Pt 9 | f | 38 | 296.23 Major Depressive Disorder, Single Episode, Severe | |

| Pt 10 | f | 21 | 296.22 Major Depressive Disorder, Single Episode, Moderate 300.40 Dysthymic Disorder | 301.4 Obsessive-Compulsive Personality Disorder 301.0 Paranoid Personality Disorder |

| Pt 11 | m | 21 | 296.22 Major Depressive Disorder, Single Episode, Moderate 300.40 Dysthymic Disorder 300.23 Social Phobia | |

| Pt 12 | f | 21 | 296.23 Major Depressive Disorder, Single Episode, Severe | |

| Pt 13 | f | 34 | 296.23 Major Depressive Disorder, Single Episode, Severe | |

| Pt 14 | f | 23 | 296.23 Major Depressive Disorder, Single Episode, Severe | 301.4 Obsessive-Compulsive Personality Disorder |

| Pt 15 | m | 21 | 296.22 Major Depressive Disorder, Single Episode, Moderate 300.40 Dysthymic Disorder | |

| Pt 16 | f | 51 | 296.22 Major Depressive Disorder, Single Episode, Moderate | |

| Pt 17 | f | 20 | 296.22 Major Depressive Disorder, Single Episode, Moderate 300.40 Dysthymic Disorder 300.81 Somatization Disorder | |

| Pt 18 | m | 31 | 296.23 Major Depressive Disorder, Single Episode, Severe 300.40 Dysthymic Disorder 300.29 Social Phobia | |

| Pt 19 | f | 38 | 296.22 Major Depressive Disorder, Single Episode, Moderate | 301.4 Obsessive-Compulsive Personality Disorder |

| Pt 20 | f | 36 | 296.22 Major Depressive Disorder, Single Episode, Moderate | |

| Pt 21 | m | 34 | 296.33 Major Depressive Disorder, Recurrent, Severe 300.40 Dysthymic Disorder | 301.4 Obsessive-Compulsive Personality Disorder |

| Pt 22 | f | 24 | 296.32 Major Depressive Disorder, Recurrent, Moderate 300.40 Dysthymic Disorder | 301.4 Obsessive-Compulsive Personality Disorder |

| Pt 23 | f | 21 | 296.23 Major Depressive Disorder, Single Episode, Severe | |

| Pt 24 | m | 27 | 296.23 Major Depressive Disorder, Single Episode, Severe | |

| Pt 25 | f | 27 | 296.23 Major Depressive Disorder, Single Episode, Severe 307.50 Eating Disorder NOS | 301.82 Avoidant Personality Disorder |

| Mean 28 |

Table 1. SEX, AGE, DSM-IV-R DIAGNOSES AT THE BEGINNING OF TREATMENT. AXIS-II DIAGNOSES AFTER 12 MONTHS OF TREATMENT

Participants

A total of 60 patients were referred to the study; 19 patients were excluded based on referral information or did not participate in the inclusion examination. The baseline study group comprised of 41 patients. Sixteen of the 41 patients in the baseline group did not start psychotherapy because of diagnostic exclusion, pregnancy, change of residence, advice to seek treatment elsewhere after the evaluation, or reverse in decision to start psychotherapy. The final study group was comprised of 25 patients (19 female, 6 male), with a mean age of 28 years (range 20–51). Twelve patients were students, ten were employed. and three unemployed. Seven patients were married, one was in a permanent relationship, three were divorced, and fourteen were single. Questionnaire responses were provided through all phases of the treatment by 22 patients and their therapists. Twenty patients decided to continue the treatment after the first year, according to the option provided.

Psychotherapy

The psychotherapy team consisted of a psychiatrist, three psychologists, and four psychiatric nurses. All patients were treated by experienced psychodynamic psychotherapists who had received formal 3-year or longer postgraduate professional training in psychodynamic psychotherapy. Their average length of experience as psychotherapists was 20 years. The team members were not involved in the development of the questionnaires.

The psychotherapy consisted of approximately 80 sessions per year, held twice a week, in the outpatient clinic of the Department of Psychiatry of Kuopio University Hospital (Saarinen et al., 2005; Tolmunen et al., 2004). The patients’ motivation and aptitude for long-term psychodynamic psychotherapy without medication was assessed by an evaluation group consisting of a psychiatrist and a psychologist and/or a specially trained nurse. In the evaluation meeting the patients received more information about the study. In order to assess the impact of the possible placebo effect of treatment expectancy prior to the initiation of psychotherapy, 14 randomly selected patients started their psychotherapy directly after the assessment and 11 randomly selected patients began after a six-month waiting period.

Design of the Questionnaires and the Timing of Administration of the Scales

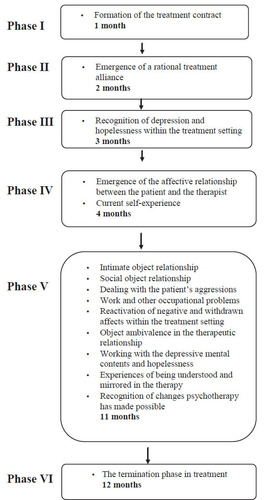

We created a process-description questionnaire to assess the conceptions and experiences of the patients and therapists at different stages of the psychodynamic psychotherapy. The creation of the questions and the scales, as well as the timing of administration of the scales (Figure 1), was based on the core dynamics of depression, clinical experience, and theory of the course of psychodynamic psychotherapy process.

Figure 1. TIMING OF ADMINISTRATION OF THE 15 MAIN SCALES

The psychotherapy team of the Department of Psychiatry, Kuopio University Hospital reviewed the questionnaires to ensure the content validity and the timing of administration, and assessed whether they were coherent and reflected the issues important to the psychotherapy process for depressed patients.

We divided the questions into 15 main scales (described in Figure 1), covering subjects regarded as central in the treatment process. These subjects included evaluations by the patients and therapists of the ongoing treatment process, as well as life situation, life-management skills, selfimage, and future opportunities of the patient. Four of the main scales were complemented by two subscales, resulting in a total of 23 scales. See paragraph subjects included in scales.

The questionnaires were mailed to patients and therapists at six stages during the first year of psychodynamic psychotherapy, following a specific protocol (Figure 1). Completed questionnaires were returned by mail to an independent researcher.

The scales were based on a total 285 items for the patients and 283 items for the therapists. The questions of the first main scale dichotomously assessed (yes/no) the opinion of the patient or therapist on the formation of the treatment relationship. The remaining scales used, a 5-point Likert scale of responses in the assessment of the scores, with 1 indicating full agreement and 5 full disagreement.

Because the first step in treatment is the establishment of a therapeutic alliance, the opinions of the patients and therapists on the formation of the treatment contract were assessed at the end of the first month of psychotherapy, when agreement on the external working schedule was reached.

The emergence of a rational treatment alliance was assessed after the second month, when the patients had gained real experiences of how the therapist worked in the therapeutic setting. The initial part of the questionnaire aimed to assess the establishment of a joint psychological frame for the treatment, which is necessary for the patient to immerse him or herself in work with mental contents on psychological matters.

The scales administered after the third month of the psychotherapy assessed the patient’s regognition of depression and hopelessness and determined how well the therapist identified the task clinical therapy for depression.

After the fourth month, the scales included questions concerning the emergence of an affective relationship between the patient and the therapist as well as the current self-image of the patient. We evaluated the affective relationship at this point because as the therapist listens to the patient’s story and develops hypotheses about the psychodynamic basis of the depression, the patient forms a transference attachment to the therapist (Gabbard, 1994). However, excessive shame and fear of exposure to the therapist can create barriers to engagement in treatment and recognition of these potential difficulties is important (Busch, Rudden, & Shapiro, 2004). Inquiry into these subjects aimed to assess the affective involvement of the patients and its potential difficulties in the treatment relationship, including injuries to the sense of self or self-esteem. These subjects were already inquired about at a relatively early phase of the therapy because evolving an affective contact with the depressed patient was regarded as particularly important. Focusing upon depressive symptoms and affects, characterized by narcissistic vulnerability, recurrent low of self-esteem and feelings of helplessness, humiliation and/or loss (Busch, Rudden, & Shapiro, 2004), was also regarded as important because symptoms may have been the patient’s first (or ostensible) reason for seeking help, and they tend to recede once therapy is established (Taylor & Richardson, 2005).

We sent the largest proportion of the scales to the participants after 11 months of psychotherapy. As therapy proceeds, the patients generally become more concerned with their lives instead of their depressive symptoms, and are more willing to work more on significant feelings, events and relationships tacitly understood as providing the foundation from which depressive symptoms developed (Taylor & Richardson, 2005). Experiences of being understood and mirrored in therapy, and recognition of the changes psychotherapy has made possible were also evaluated after 11 months of psychotherapy. An important step in the consolidation of the changes in respect of inquired subjects during the treatment is based upon the patient’s internalization of the therapist’s consistent attitude towards life experiences and the mental states associated with them (Taylor & Richardson, 2005).

The final group of questions (Scale 15) concerned the termination phase of the treatment. These were sent at the end of the first year of treatment to those patients who terminated their treatment. The scale aimed to clarify how the patient’s situation had changed during the psychotherapy process, considering among others his or her depressive symptoms, self-esteem, life-management skills and object relationships. The final scale was not analyzed in this study, because the majority of the patients (n = 20) continued their treatment after the first year.

Subjects Included in Scales

The subjects of the scales noted in figure 1 were chosen to assess intimate and social object relationships, the capacity to deal with frustration and its concomitant aggression (constructive or destructive force), reactivation of negative and withdrawn affects within the therapeutic relationship, object ambivalence in the therapeutic relationship, working with the depressive mental contents and hopelessness as well as working with occupational problems. Evaluation of the effect of the therapy process on these items requires some time before their working through can be assessed.

The main scales considering intimate and social object relationships, work and other occupational problems were complemented by two subscales. The first subscale for each of these main scales considered the current state of the subject and the second subscale considered the therapeutic work on the subject in the psychotherapy relationship. The main scale considering object ambivalence in the therapeutic relationship was complemented by subscales considering positive and negative affects and thoughts about the therapists.

Statistical Analysis

Paired samples t-tests were used to compare mean scores for the main scales and subscales of the patients and therapists, except for scale 1 (Table 2). If necessary, some Likert scales were calculated in reverse to make them consistent with the subject of the scale. The Bonferroni correction for multiple comparisons was also applied.

| Paired samples t-test | |||||||

| Patient | Therapist | ||||||

| mean | SD | mean | SD | t | P | ||

| Main scale 2 | Emergence of a rational treatment alliance | 1.58 | ±0.94 | 1.74 | ±0.54 | -0.71 | 0.478 |

| Main scale 3 | Recognition of depression and hopelessness within the treatment setting | 3.13 | ±0.90 | 2.78 | ±0.66 | 1.84 | 0.079 |

| Main scale 4 | Emergence of the affective relationship between the patient and the therapist | 3.28 | ±0.55 | 2.47 | ±0.31 | 5.59 | 0.000 |

| Main scale 5 | Current self experience | 2.66 | ±0.67 | 2.76 | ±0.65 | 0.55 | 0.591 |

| Main scale 6 | Intimate object relationships | 2.14 | ±0.49 | 1.96 | ±0.52 | 1.20 | 0.246 |

| Subscale 6a | State of the patient’s intimate object relationships | 1.70 | ±0.54 | 1.78 | ±0.61 | -0.40 | 0.686 |

| Subscale 6b | Dealing with the patient’s intimate object relationships | 2.56 | ±0.59 | 2.12 | ±0.47 | 2.12 | 0.005 |

| Main scale 7 | Social object relationships | 2.23 | ±0.49 | 2.14 | ±0.52 | 0.62 | 0.534 |

| Subscale 7a | State of the patient’s social object relationships | 1.85 | ±0.53 | 2.17 | ±0.75 | -1.94 | 0.067 |

| Subscale 7b | Dealing with the patient’s social relationships | 2.61 | ±0.63 | 2.12 | ±0.47 | 3.34 | 0.003 |

| Main scale 8 | Dealing with the patient’s aggressions | 2.77 | ±0.45 | 3.26 | ±0.52 | -3.86 | 0.001 |

| Main scale 9 | Work and other occupational problems | 2.65 | ±0.50 | 2.51 | ±0.52 | 0.87 | 0.389 |

| Subscale 9a | State of the patient’s work and occupational problems | 3.08 | ±0.82 | 2.92 | ±0.91 | 0.70 | 0.495 |

| Subscale 9b | Dealing with the patient’s work and occupational problems | 2.15 | ±0.54 | 2.17 | ±0.72 | -0.12 | 0.907 |

| Main scale 10 | Reactivation of negative and withdrawn affects within the therapeutic relationship | 4.16 | ±0.48 | 3.90 | ±0.81 | 1.69 | 0.107 |

| Main scale 11 | Object ambivalence in the therapeutic relationship | 3.92 | ±0.34 | 3.57 | ±0.34 | 2.94 | 0.008 |

| Subscalella | Positive affects and thoughts | 3.20 | ±0.60 | 3.10 | ±0.47 | 0.99 | 0.335 |

| Subscalellb | Negative affects and thoughts | 4.64 | ±0.58 | 4.04 | ±0.69 | 3.41 | 0.003 |

| Main scale 12 | Working with the depressive mental contents and hopelessness | 2.49 | ±0.64 | 2.41 | ±0.57 | 0.54 | 0.587 |

| Main scale 13 | Experiences of being understood and mirrored in the therapy | 1.92 | ±0.71 | 1.77 | ±0.57 | 1.09 | 0.289 |

| Main scale 14 | Recognition of changes psychotherapy has made possible | 2.56 | ±0.71 | 2.39 | ±0.68 | 1.14 | 0.270 |

Table 2. COMPARISONS OF THE MEAN SCORES OF PATIENTS AND THERAPISTS. 1 = FULL AGREEMENT, 5 = FULL DISAGREEMENT

The independent samples t-test was used to validate the questionnaires when comparing the scores of the patients who started therapy immediately after initial assessment with those placed on a waiting list.

Cronbach’s alpha was used to evaluate the internal consistency of the main scales and subscales (Cronbach et al., 1972). The coefficient of variation (CV) was assessed to measure the dispersion of the probability distribution between the patients and their therapists in the main scales and subscales. Levene’s test was applied to assess the equality of variances between the patients and the therapists in the main scales and subscales. To measure the degree of correlation between the patients and the therapists, Spearman’s correlation coefficient was calculated for the main scales and subscales.

Results

There were no significant differences between in the scores of the therapists and patients in the group that started psychotherapy immediately after assessment and the group starting treatment after a six-month waiting period.

When the scores for all therapists and patients, i.e. those randomized to start treatment immediately and those randomized to the six-month waiting period, were pooled, significant differences appeared in six main scales or subscales in the different phases of the treatment, two of which remained significant after Bonferroni correction (Table 2).

The mean coefficient of variation between the patients and the therapists was 21.3%, ranging from 10.4% in the subscale concerning the patients’ positive affects and thoughts to 43% in the scale concerning the emergence of a rational treatment setting (Table 3).

| Coefficient of variation | |||

| Label/theme | SD | CV % | |

| Main scale 1 | Formation of the treatment contract | 0.20 | 11.4 |

| Main scale 2 | Emergence of a rational treatment alliance | 0.71 | 43.0 |

| Main scale 3 | Recognition of depression and hopelessness within the treatment setting | 0.62 | 20.8 |

| Main scale 6 | Intimate object relationships | 0.49 | 24.1 |

| Main scale 4 | Emergence of the affective relationship between the patient and the therapist | 0.72 | 25.1 |

| Main scale 5 | Current self experience | 0.55 | 20.4 |

| Main scale 6 | Intimate object relationships | 0.49 | 24.1 |

| Subscale 6a | State of the patient’s intimate object relationships | 0.61 | 35.3 |

| Subscale 6b | Dealing with the patient’s intimate object relationships | 0.54 | 23.1 |

| Main scale 7 | Social object relationships | 0.39 | 17.8 |

| Subscale 7a | State of the patient’s social object relationships | 0.59 | 29.4 |

| Subscale 7b | Dealing with the patient’s social relationships | 0.58 | 24.4 |

| Main scale 8 | Dealing with the patient’s aggressions | 0.51 | 16.9 |

| Main scale 9 | Work and other occupational problems | 0.51 | 19.7 |

| Subscale 9a | State of the patient’s work and occupational problems | 0.78 | 26.1 |

| Subscale 9b | Dealing with the patient’s work and occupational problems | 0.49 | 22.7 |

| Main scale 10 | Reactivation of negative and withdrawn affects within the therapeutic relationship | 0.52 | 13.0 |

| Main scale 11 | Object ambivalence in the therapeutic relationship | 0.45 | 11.9 |

| Subscale11a | Positive affects and thoughts | 0.33 | 10.4 |

| Subscale11b | Negative affects and thoughts | 0.69 | 16.0 |

| Main scale 12 | Working with the depressive mental contents and hopelessness | 0.46 | 18.8 |

| Main scale 13 | Experiences of being understood and mirrored in the therapy | 0.44 | 23.7 |

| Main scale 14 | Recognition of changes psychotherapy has made possible | 0.44 | 17.7 |

| Mean | 0.53 | 21.44 | |

Table 3. COEFFICIENT OF VARIATION OF THE ESTIMATION BETWEEN THE PATIENTS AND THE THERAPISTS

In the initial phase, at the end of the first month of psychotherapy, the items of the scale inquiring into the formation of the treatment contract were evaluated. The formation of the treatment contract had been agreed upon in the estimations of the therapists and the patients, respectively, in 86% and 74% of these items.

The scales assessed after four months of therapy indicated that the therapists experienced more strongly than their patients that an affective relationship between them had emerged (Table 2).

After 11 months of therapy, differences between the patients and the therapists appeared in several scales covering the areas of life of the patient and the subjects of the treatment relationship (Table 2).

In the subscale concerning the psychotherapeutic work on intimate object relationships, the therapists felt more strongly than did the patients that the patients had begun to better understand the quality of their intimate object relationships and how their personal life histories and subjective experiences influence these relationships.

In the subscale concerning the psychotherapeutic work on social object relationships, therapists felt more strongly than the patients that the latter had begun to better understand the quality of their social object relationships and how their personal life history influenced these relationships.

In the main scale concerning the capacity to deal with aggression, the therapists experienced more strongly that the patients had problems in dealing with their aggression.

In the main scale dealing with object ambivalence in the therapeutic relationship, the patients estimated less ambivalence being present in the relationship. There was no difference in the subscale considering positive affects and thoughts. In the subscale considering negative affects and thoughts, the therapists experienced more strongly that patients had negative thoughts and affects towards the therapist.

After Bonferroni correction (p < 0.0024), significant differences remained in the main scales concerning the emergence of an affective relationship and the capacity to deal with frustration and aggression. In both, the therapists estimated that patients had more problems in these respects than the patients themselves.

The mean value of Cronbach’s alpha was 0.84 for the patient scales, range 0.595–0.941, and 0.82 for the therapist scales, range 0.357–0.952 (Table 4).

| Patients | Therapists | ||||||

| Label/theme | N of Cases | N of Items | Alpha | N of Cases | N of Items | Alpha | |

| Main scale 1 | Formation of the treatment contract | 18 | 16 | 0.807 | 22 | 19 | 0.857 |

| Main scale 2 | Emergence of a rational treatment alliance | 22 | 7 | 0.923 | 22 | 8 | 0.901 |

| Main scale 3 | Recognition of depression and hopelessness within the treatment setting | 22 | 20 | 0.941 | 22 | 20 | 0.850 |

| Main scale 4 | Emergence of the affective relationship between the patient and the therapist | 21 | 18 | 0.850 | 21 | 17 | 0.357 |

| Main scale 5 | Current self experience | 18 | 25 | 0.910 | 22 | 25 | 0.923 |

| Main scale 6 | Intimate object relationships | 21 | 24 | 0.891 | 22 | 24 | 0.912 |

| Subscale 6a | State of the patient’s intimate object relationships | 21 | 15 | 0.879 | 22 | 15 | 0.896 |

| Subscale 6b | Dealing with the patient’s intimate object relationships | 22 | 9 | 0.751 | 22 | 9 | 0.689 |

| Main scale 7 | Social object relationships | 22 | 21 | 0.847 | 22 | 21 | 0.899 |

| Subscale 7a | State of the patient’s social object relationships | 22 | 13 | 0.815 | 22 | 13 | 0.911 |

| Subscale 7b | Dealing with the patient’s social relationships | 22 | 8 | 0.766 | 22 | 8 | 0.691 |

| Main scale 8 | Dealing with the patient’s aggressions | 17 | 29 | 0.775 | 20 | 29 | 0.904 |

| Main scale 9 | Work and other occupational problems | 19 | 21 | 0.854 | 21 | 20 | 0.852 |

| Subscale 9a | State of the patient’s work and occupational problems | 19 | 14 | 0.908 | 21 | 14 | 0.916 |

| Subscale 9b | Dealing with the patient’s work and occupational problems | 21 | 7 | 0.718 | 22 | 6 | 0.886 |

| Main scale 10 | Reactivation of negative and withdrawn affects within the therapeutic relationship | 22 | 20 | 0.832 | 20 | 20 | 0.939 |

| Main scale 11 | Object ambivalence in the therapeutic relationship | 22 | 19 | 0.595 | 22 | 19 | 0.499 |

| Subscale 11a | Positive affects and thoughts | 22 | 10 | 0.700 | 22 | 10 | 0.485 |

| Subscale 11b | Negative affects and thoughts | 22 | 9 | 0.893 | 22 | 9 | 0.815 |

| Main scale 12 | Working with the depressive mental contents and hopelessness | 21 | 16 | 0.910 | 22 | 15 | 0.874 |

| Main scale 13 | Experiences of being understood and mirrored in the therapy | 22 | 11 | 0.934 | 22 | 11 | 0.939 |

| Main scale 14 | Recognition of changes psychotherapy has made possible | 18 | 20 | 0.926 | 22 | 20 | 0.952 |

| Mean | 19.91 | 16.52 | 0.84 | 20.83 | 16.52 | 0.82 | |

Table 4. CRONBACH’S ALPHA OF THE ESTIMATION BETWEEN PATIENTS AND THERAPISTS

In the main scale concerning the emergence of an affective relationship between the therapist and the patients, the variance was larger among the patients (F = 8.84, p = 0.005). In the subscale concerning the state of the patients’ social object relationships (F = 4.42, p = 0.041) and in the main scale concerning the reactivation of negative and withdrawn affects within the therapeutic relationship (F = 5.05, p = 0.030), the variance was larger among the therapists.

There were significant correlations between the patients and the therapists in the main scales concerning the recognition of depression and hopelessness within the treatment setting (r = 0.46, p = 0.037), social object relationships (r = 0.44, p = 0.040), work with depressive mental contents and hopelessness (r = 0.53, p = 0.014), experiences of being understood and mirrored in the therapy (r = 0.51, p = 0.015), recognition of changes psychotherapy had made possible (r = 0.54, p = 0.012), and in the subscale concerning positive affects and thoughts (r = 0.58, p = 0.005).

Discussion

The primary goal of this study was to investigate and compare patients’ and therapists’ experiences of the psychodynamic psychotherapy process for depression during the first year of treatment. The investigation was carried out to quantify the crucial elements of the interaction between the patient and therapist and to evaluate the processing of object relationships and life conditions in a patient during psychotherapy for depression.

This report concentrates on describing the findings of the process contents, patient-therapist correlations, and the reliability of the questionnaire. The validity of the questionnaire was confirmed by an independent assessment team and by the observation that there were no significant differences in the views of the patients and the therapists in the groups starting psychotherapy directly after the assessment and the control group starting therapy after a six-month waiting period. We recognize, however, that further validation by other methods is called for.

The internal consistency of the scales and subscales was assessed by Cronbach’s alpha, for which α values of 0.7 to 0.8 are regarded as satisfactory (Bland & Altman, 1977). The mean α was 0.84 for the patient scales and 0.82 for the therapist scales, which represents good internal consistency and supports the reliability of the scales. The mean variance (21.3%) between the estimations of patients and their therapists was relatively low, which further supports the reliability of the questionnaire.

The main finding after Bonferroni correction was the prevailing concordance between the views of the patients and therapists in most of the scales, which was supported by significant correlations between the items indicating tuning between the therapeutic couple. However, differences were found in the scales concerning the emergence of an affective relationship and the patients’ capacity to deal with frustration and aggression. The therapists experienced more strongly than the patients that the patients had problems in dealing with aggression, although the variance of their responses was higher than that of the patients. The therapists also experienced more strongly than patients that an affective relationship with their patient had emerged. The variance among the patients’ estimations for this subject was significantly higher compared to the response variance of the therapists, probably suggesting that the patients were having difficulties in maintaining a lively affective relationship with their therapists.

After 11 months of psychotherapy, several significant differences appeared, but only in calculations uncorrected by the Bonferroni procedure. The subscales concerning psychotherapeutic work on intimate and social object relationships suggested that therapists estimated more improvement having taken place among the patients in the understanding of these relationships compared with the patients’ own views. This may indicate more accurate observation by the therapists in comparison to the more inhibited subjective experiences of the patients in the midst of their probably more biased perception. However, in principle, this finding may also have been affected by the therapeutic ambition of the therapists. The good concordance of estimations as shown in the significant correlations of patient-therapist scores regarding mirroring and the recognition of depressive subjects during the process suggest, however, that work in the therapeutic couple was well tuned and not dominantly driven by the conceptions of the therapist

The scale concerning object ambivalence in the therapeutic relationship suggested, again only in Bonferroni uncorrected calculations, that therapists estimated more activation of affects and thoughts towards them than the patients did. Especially in the subscale concerning negative affects and thoughts, a discrepancy between the therapists and their patients seemed prominent. Negative counter-feelings in the therapists might have influenced this finding. However, on the basis of the significant positive correlations in the scales indicating mutual tuning in the therapeutic couple, we regard the effect of biased counterfeelings of the therapists less likely than their constructive capacity and sensitivity in observing and dealing with affective material, as well as its possible absence, based on their professional training.

Our findings are in line with the view that a depressed patient has difficulties in experiencing affects on a conscious level and expressing them, especially in regard to negative affects and inhibited anger (Luutonen, 2007). This may contribute to the discrepancy in views of the patients and therapists in the scales concerning the capacity to deal with aggression, the emergence of an affective relationship, and the higher variance among the patients’ estimations of these subjects.

Based on concordance of estimations and several positive correlations between the patients and therapists, our findings indicate a relatively good treatment alliance, tuning in the therapeutic couple, and a similar estimation of reality-oriented subjects. The therapeutic challenges seemed to be focused mainly on affective and potentially negative subjects, which were asymmetrically observed by the therapeutic couple. It seemed that negative affects were not markedly activated in the patients during the first year of the psychotherapy process.

The more neutral aspects of the life situation with some individual variation, as noted in a case report published earlier (Saarinen et al., 2005), yielded concordant views in the therapeutic couple. The differences in the analysis of variance also indicated asymmetry in conceptions between the therapists and patients for affective and negative subjects, in contrast to significant positive correlations for affectively more neutral subjects.

However, two principal points require attention when evaluating our results. Both the patients and therapists were aware that the therapy process was part of a research project. We were unable to control for, or assess, the influence of this setting on the therapy process. The reports of the therapists at research meetings did not, however, support the presence of a significant bias in this respect. Information given by the therapists indicated that the process proceeded in the usual way and the research protocols did not intervene in or significantly disturb the therapeutic work.

Another concern relates to the asymmetry of estimations for affective and negative subjects and their relation to the concordance of estimations of the more neutral subjects between the patients and therapists. In principle, the estimations of affects may have been influenced by methodological, theoretical, and/or personal bias of the therapists or by suboptimal use of the therapeutic method. However, the concordance shown by several positive correlations in the estimations of the patients and therapists of items reflecting the working alliance and the life conditions of the patients suggests that the relationship was psychologically well tuned and adjusted to the life situations of the subjects. In the light of such indicators of good mutual tuning, the differences in their perceptions regarding affective and negative subjects are unlikely explained by methodological factors. Rather than caused by measurement inaccuracy or differences in internal scales of the therapeutic couple, they more likely represent genuine differences in affect perception by the patients and therapists. The findings suggest that the challenge of depression is indeed addressed by the therapists in a different, asymmetrical way in comparison with the patients and in accordance with the general rule that an asymmetrical relation between the therapist and patient is a prerequisite for the creation of an effective psychological working process.

Limitations of the Study

The small size of the sample (25 patients and eight therapists) limits the generalization of our findings. Although Cronbach’s alpha indicated that the reliability of the scales was generally high, it remained low in some scales (Table 4). This might have been a consequence of ambiguous or confusing questions for these scales, or difficulty of the patients and therapists in similarly assessing the subject of these scales, as was discussed above. We did not remove any questions to correct the alpha in any of the scales in order to assess the reliability of the designed questionnaire in its original form.

Assessment of the validity of the scales remains incomplete in this study and requires further work. Altogether, 20 of the 25 patients in this study continued with psychotherapy after the first year, which might have caused heterogeneity in the therapeutic relationships of our sample, and thus also limits the generalisation of our findings. Because this is a preliminary study, and the instrument we used is new, we do not have repeated measures with the same scale to present or comparative findings of our questionnaire with other samples. Before further validation is done, the findings of this study remain to have an explorative character. However, despite the statistical limitations, our findings appear clinically relevant, and are in line with the theory of the asymmetrical nature of the therapeutic alliance of psychodynamic psychotherapy.

Conclusions

During the first year of psychodynamic psychotherapy for depression, the estimations of the patients and therapists concerning their views and experiences of the therapeutic process were mainly congruent and had significant correlations in items indicating mutual tuning in the therapeutic couple. However, their estimations differed significantly with respect to affective and negatively loaded subjects during the first year of the therapy process. Affectively more neutral subjects, such as those related to the life situation and tuning to treatment, were estimated in a congruent way. It appears that the subjects in the treatment process with potentially negative meaning, such as frustrated or angry feelings, are not activated to any significant degree in the therapeutic relationship during the first year of psychodynamic psychotherapy for depression, which is probably due to a more general inhibition of the expression of affects in a depressive state. These findings emphasize the importance of the development of a good treatment relationship and the capacity of the therapists to anticipate and assist patients with depression in the expression of affective subjects, including those carrying feelings of frustration and anger.

(1995). Psychotherapy versus medication for depression: challenging the conventional wisdom with data. Professional Psychology: Research and Practice, 26(6), 574–585.Crossref, Google Scholar

(1962). Dimensions of therapist response as causal factors in therapeutic chance. Psychological Monographs, 76(43), 562.Crossref, Google Scholar

(1977). Statistics notes: Cronbach’s alpha. British Medical Journal, 314, 572.Crossref, Google Scholar

(2004). Psychodynamic Treatment of Depression: Development of a psychodynamic model of depression (pp. 13–30). Arlington: American Psychiatric Publishing, Inc.Google Scholar

, (2009). Comparative efficacy and acceptability of 12 new-generation antidepressants: a multiple-treatments meta-analysis. Lancet, 373(9665), 746–58.Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

(1972). The Dependability of Behavioural Measurements: Theory of Generalizability for Scores and Profiles. New York: John Wiley & Sons.Google Scholar

(2007). Therapists affect focus and patient outcomes in psychodynamic psychotherapy: a meta-analysis. American Journal of Psychiatry, 164(6), 936–941.Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

(1994). Psychodynamic psychiatry in clinical practice: the DSM-IV edition (pp. 235–237). Washington, DC: American psychiatric press, Inc.Google Scholar

(1960). A rating scale for depression. Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery, and Psychiatry, 23, 56–61.Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

, (2000). Social functioning in depression: a review. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, 61(4), 268–275.Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

, (2007). Reduced midbrain serotonin transporter availability in drug naive patients with depression measured by SERT-specific [(123) I] nor-beta-CIT SPECT imaging. Psychiatry Research, 154(2), 125–131.Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

, (2000). Psychosocial disability during the long-term course of unipolar major depressive disorder. Archives of general psychiatry, 57(4), 375–380.Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

(1996). Practice guideline for major depressive disorder in adults: Disease definition, epidemiology, and natural history. In American Psychiatric Association, Practice guidelines (pp. 143–145). Washington, D.C.Google Scholar

(2007). Association of different adverse life events with distinct patterns of depressive symptoms. American Journal of Psychiatry, 164(10), 1521–1529.Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

(2004). The interrelationship of neuroticism, sex, and stressful life events in the prediction of episodes of major depression. American Journal of Psychiatry, 161(4), 631–636.Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

(2001) Gender differences in the rates of exposure to stressful life events and sensitivity to their depressogenic effects. American Journal of Psychiatry, 158(4),587–593.Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

, (1996). The role of the therapeutic alliance in psychotherapy and pharmacotherapy outcome: findings in the National Institute of Mental Health Treatment of Depression Collaborative Research Program. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 64(3), 532–539.Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

, (2008). Changes in midbrain serotonin transporter availability in atypically depressed subjects after one year of psychotherapy. Progress in Neuro-psychopharmacology & Biological Psychiatry, 32(1), 229–237.Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

, (2008). Midbrain serotonin and striatum dopamine transporter binding in double depression: a one-year follow-up study. Neuroscience Letters, 441(3), 291–295.Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

(2007). Anger and depression – Theoretical and clinical considerations. Nordic Journal of Psychiatry, 61(4), 246–251.Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

(2006). Depression research and treatment: are we skating to where the puck is going to be? Clinical Psychology Review, 26, 985–999.Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

(2001). Brain blood flow changes in depressed patients treated with interpersonal psychotherapy or venlafaxine hydrocloride. Archives of General Psychiatry, 58, 641–648.Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

(1981). Therapeutic alliance scales: development and relationship to psychotherapy outcome. American Journal of Psychiatry, 138(3), 361–364.Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

(1978). A new depression scale designed to be sensitive to change. British Journal of Psychiatry, 134, 382–389.Crossref, Google Scholar

(2005). Psychodynamic psychotherapy and treatment of depression. Psychiatry, 4(5), 6-9.Crossref, Google Scholar

(1992). Rating scales for special purposes. I: Psychotherapy Research Methods in Psychiatry. In Freeman, C.Tyrer, P. (Eds.), Research Methods in Psychiatry: A Beginners Guide (2th ed.), (pp. 247–272). London: The Royal College of Psychiatrists.Google Scholar

, (2003). Differential responses to psychotherapy versus pharmacotherapy in patients with chronic forms of major depression and childhood trauma.

, (2005). An outcome of psychodynamic psychotherapy: a case study of the change in serotonin transporter binding and the activation of the dream screen. American Journal of Psychotherapy, 59(1), 61–73.Link, Google Scholar

(2008). Theory, technique, and process in psychodynamic psychotherapy. In Levy, A. R.Ablon, J. S. (Eds.), Handbook of evidence-based psychodynamic psychotherapy (pp. 201–226). New York: Humana PressGoogle Scholar

(1980). Measurement of the impact of psychotherapy sessions. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 48(2), 176–185.Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

(2005). The psychoanalytic/psychodynamic approach to depressive disorder. In Gabbard, G.O.Beck, S.J.Holmes, J. (Eds), Oxford Textbook of Psychiatry (pp. 127–136). Oxford: Oxford University PressGoogle Scholar

, (2004). Elevated midbrain serotonin availability in mixed mania: a case report. BMC Psychiatry, 4(13), 27.Medline, Google Scholar

(1967). Toward effective counselling and psychotherapy. Chicago: Aldine Publishing.Google Scholar

(1993). Mind and its treatment: a psychoanalytic approach. Madison: International Universities Press.Google Scholar

(1991). Concise guide to: Psychodynamic psychotherapy. Washington D.C: American Psychiatric Press.Google Scholar

(2001). The great psychotherapy debate. New Jersey: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Inc., Publishers.Google Scholar