Supervisor Allegiance as a Critical Construct: A Brief Communication

Abstract

Allegiance, long regarded as a significant variable in psychotherapy and psychotherapy research, has been ignored in the psychotherapy supervision literature. It is our contention that allegiance is similarly significant for psychotherapy supervision. In this brief communication, we define supervisor allegiance, consider its impact on supervision outcome, and highlight its role in the contextual supervision relationship model (a trans-theoretical model of the supervisory relationship).

Allegiance, the therapist’s or researcher’s belief in treatment effectiveness, has long been regarded as a significant variable in psychotherapy and psychotherapy research (Luborsky et al., 1999). Therapist allegiance is now generally agreed upon as being outcome affecting (McLeod, 2009), need for its continued empirical examination widely recognized and accepted (Leykin & DeRubeis, 2009; Munder, Brutsch, Gerger, & Barth, 2013; Wampold & Imel, 2015). Supervisor allegiance is the supervisory equivalent of therapist allegiance and similarly appears to be outcome affecting, a potentially significant variable that merits empirical examination. But supervisor allegiance has gone unmentioned and unexamined in the supervision literature. We argue this needs to change. The supervisor’s allegiance may be integral to understanding a host of supervision variables, ranging from inadequate and harmful supervision to adequate and expert supervision (e.g., Ayala, Ellis, Kotary, Berger, & Hanus, 2015; Ellis, Berger, Hanus, Ayala, Swords, & Siembor, 2014).

Supervisor Allegiance in Theoretical Context

A Contextual Supervision Relationship Model

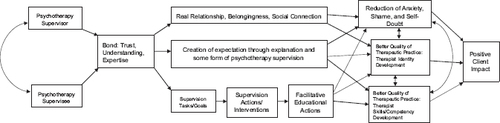

The contextual supervision relationship model (CSRM) serves as the theoretical framework upon which we base our allegiance proposals (Watkins, 2016; Watkins, Budge, & Callahan, 2015; Watkins, Wampold, & Budge, 2015); it is the only supervision model that assigns substantial weight to supervisor allegiance as being process/outcome affecting. The CSRM, a supervisory extrapolation of Wampold’s contextual psychotherapy relationship model (Budge & Wampold, 2015; Imel & Wampold, 2008; Wampold, 2001, 2007, 2010a, 2010b; Wampold & Budge, 2012; Wampold & Imel, 2015), is transtheoretical in nature and privileges relational connection, expectations/goals, and supervisory action.Figure 1 provides a graphic representation of the CSRM (for more model information, see Watkins, 2016; Watkins, Budge et al., 2015). Using the CSRM as foundation, we provide our perspective on why supervisor allegiance matters and briefly elaborate upon how it impacts supervision.

Figure 1 THE RELATIONSHIP IN PSYCHOTHERAPY SUPERVISION

Line connecting the Supervisor and Supervisee blocks has been added, indicating that both parties enter the supervisory situation with their respective thoughts, ideas, and expectations about the other. (Adapted from Watkins [2016] with permission of the American Psychological Association).

Supervisor Allegiance: What Is It? Why Does It Matter?

Supervisor Allegiance Definition and Significance

Supervisor allegiance can most simply be defined as belief in supervision effectiveness. Ideally, the supervisor has conviction that supervision works (that it substantively contributes to therapist growth and has positive client impact) and accordingly provides conviction-consistent, growth-inducing supervision experiences. But any theoretical discussion about supervisor allegiance is missing, as is any empirical study about its supervisory impact (e.g., Bernard & Goodyear, 2014; Hess, Hess, & Hess, 2008; Watkins & Milne, 2014; based on Google Scholar search using the words “allegiance”, “supervision”, and “supervisor”).

We contend that, just as “patients want to know that their therapist believes in the treatment being provided” (Wampold & Imel, 2015, p. 275), supervisees want to know that their supervisor believes in the supervision being delivered. In the CSRM (Watkins, 2016; Watkins, Budge et al., 2015), supervisor allegiance is a pivotal common factor, creating supervisee expectations for change, increasing the likelihood of both effective supervision being delivered and a positive supervision outcome occurring. We propose that supervisor allegiance involves at least two inextricably intertwined components: (a) the degree to which the supervisor believes in and has conviction about the particular supervision being provided, and (b) the supervisor’s motivation to practice supervision. The supervisor is allegiant to the implemented form of supervision and to the enterprise of supervision as an educational practice. Both conviction and motivation have been implicated in therapist allegiance (McLeod, 2009), and we see it as being no different for supervision.

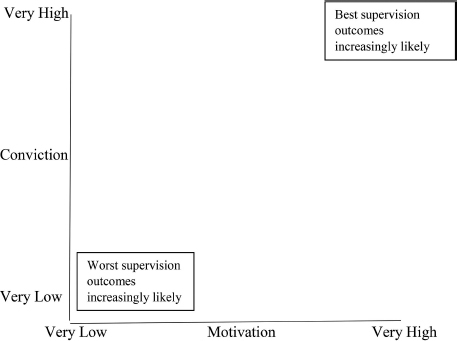

Quality and fidelity appear most affected by supervisor allegiance. According to our model’s prediction, supervisors rating high on both allegiance dimensions would (a) have the best supervision outcomes (positively impacting outcome goals; Figure 1) and (b) show greater practice fidelity (e.g., in manual-driven supervision research; Milne, 2010, 2014). Conversely, supervisors low on both dimensions would have the worst supervision outcomes and poorest practice fidelity. Figure 2 provides a graphic depiction of the possible supervisor allegiance/supervision outcome relationships. Where the dimensions meet in the middle, mediocre, mixed results would be expected. Low/high variations can exist for myriad reasons, some examples follow: A new supervisor is struggling to define herself theoretically and is quite dissatisfied with her supervision approach (low conviction), yet is very committed to learning supervision and being an effective supervision practitioner (high motivation); or a seasoned supervisor is highly satisfied with his supervisory approach (high conviction), but is tired of doing supervision, needs a break, and feels burned out (low motivation). If supervisor allegiance is to be most specifically considered conceptually and empirically, we contend that factoring both proposed dimensions into supervision study is absolutely essential.

Figure 2 PROPOSED SUPERVISOR ALLEGIANCE EFFECTS ON SUPERVISION OUTCOME (therapist identity development and skills/competence development; positive client impact).

Measuring Supervisor Allegiance

Wampold and Imel (2015) state that therapist allegiance, though difficult to study, must always be given attention. We believe that same statement could be said about supervisor allegiance, but no allegiance measure exists to drive supervision research. Developing an adequate supervisor allegiance scale or means of measurement (e.g., self-report, observational ratings) is a prerequisite, what we see as preeminent priority. Altering existing therapist allegiance measures to fit the supervisory role could work (e.g., making the self-report/external ratings therapy allegiance measure of Luborsky et al. [1999] supervision ready), provided appropriate therapy to supervision scale validation steps are taken (Ellis, D’Iuso, & Ladany, 2008; Ellis & Ladany, 1997). The formidable challenge of measurement must be aggressively confronted if supervisor allegiance study is to profitably proceed.

The Way Forward

But before the measurement challenge can be confronted, before any research can be done, supervisor allegiance must first be recognized as a variable of import. For supervisor allegiance not to even be acknowledged (or acknowledged minimally) in the literature is a gross omission. We argue for correction: Supervisor allegiance sorely needs to be made part of the supervisory conversation and considered for its potentially powerful supervision impact.

(2015). Exceptional clinical supervision: Testing a taxonomy and assessing occurrence.

(2014). Fundamentals of clinical supervision (5th ed.). Upper Saddle River, NJ: Merrill.Google Scholar

(2015). The relationship: How it works. In O. C. G. GeloA. PritzB. Rieken (Eds.), Psychotherapy research: Foundations, process, and outcomes (pp. 213-228). Dordrecht: Springer.Crossref, Google Scholar

(2014). Inadequate and harmful clinical supervision: Testing a revised framework and assessing occurrence. The Counseling Psychologist, 42, 434-472.Crossref, Google Scholar

(2008). State of the art in assessment, measurement, and evaluation of clinical supervision. In A. K. HessK. D. HessT. A Hess (Eds.), Psychotherapy supervision: Theory, research, and practice (2nd ed., pp. 473-499). Hoboken, NJ: Wiley.Google Scholar

(1997). Inferences concerning supervisees and clients in clinical supervision: An integrative review. In C. E. Watkins, Jr. (Ed.), Handbook of psychotherapy supervision (pp. 447-507). New York: Wiley.Google Scholar

Hess, A. K.Hess, K. D.Hess, T. H. (Eds.). (2008). Psychotherapy supervision: Theory, research, and practice (2nd ed.). Hoboken, NJ: Wiley.Google Scholar

(2008). The importance of treatment and the science of common factors in psychotherapy. In S. D. BrownR. W. Lent (Eds.), Handbook of counseling psychology (4th ed., pp. 249-266). New York: John Wiley.Google Scholar

(1999). The researcher’s own therapy allegiances: A “wild card” in comparisons of treatment efficacy. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice, 6, 95-106.Crossref, Google Scholar

(2009). Understanding why therapy allegiance is linked to clinical outcomes. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice, 16, 69-72.Crossref, Google Scholar

(2010). Can we enhance the training of clinical supervisors? A national pilot study of an evidence-based approach. Clinical Psychology and Psychotherapy, 17, 321-328.Medline, Google Scholar

(2014). Beyond the ‘acid test’: A conceptual review and reformulation of outcome evaluation in clinical supervision. American Journal of Psychotherapy, 68, 213-230.Link, Google Scholar

(2013). Researcher allegiance in psychotherapy outcome research: An overview of reviews. Clinical Psychology Review, 33, 501-511.Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

(2001). The great psychotherapy debate: Models, methods, and findings. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.Google Scholar

(2007). Psychotherapy: The humanistic (and effective) treatment. American Psychologist, 62, 857-873.Crossref, Google Scholar

(2010a). The basics of psychotherapy: An introduction to theory and practice. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association.Google Scholar

(2010b). The research evidence for the common factors models: A historically situated perspective. In B. L. DuncanS. D. MillerB. E. WampoldM. A. Hubble (Eds.), The heart and soul of change (2nd ed.; pp. 49-81). Washington, DC: American Psychological Association.Crossref, Google Scholar

(2012). The 2011 Leona Tyler Award address: The relationship—and its relationship to the common and specific factors of psychotherapy. The Counseling Psychologist, 40, 601-623.Crossref, Google Scholar

(2015). The great psychotherapy debate: The evidence for what makes psychotherapy work (2nd ed.). Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.Crossref, Google Scholar

(2016). How does psychotherapy supervision work? Contributions of connection, conception, allegiance, alignment, and action. Journal of Psychotherapy Integration. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/int0000058 (available online)Google Scholar

(2015). Common and specific factors converging in psychotherapy supervision: A supervisory extrapolation of the Wampold/Budge psychotherapy relationship model. Journal of Psychotherapy Integration, 25, 214-235.Crossref, Google Scholar

Watkins, C. E., Jr.Milne, D. (Eds.). (2014). Wiley international handbook of clinical supervision. Oxford, United Kingdom: Wiley.Crossref, Google Scholar

(2015, August). Extrapolating the Wampold/Budge model of the psychotherapy relationship to psychotherapy supervision.