“The Ickiness Factor:” Case Study of an Unconventional Psychotherapeutic Approach to Pediatric OCD

Abstract

Obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD) is a complex condition with biological, genetic, and psychosocial causes. Traditional evidence-based treatments include cognitive-behavioural therapy, either alone or in combination with serotonin-specific reuptake inhibitors (SSRI’s), other serotonergic agents, or atypical antipsychotics. These treatments, however, often do not lead to remission, and therefore, it is crucial to explore other less conventional therapeutic approaches. This paper describes a case study in which psychodynamic, narrative, existential, and metaphor therapy in combination with more conventional treatments led to a dramatic remission of severe OCD in a 12 year old hospitalized on a psychiatric inpatient unit. The paper, which is written partly in the form of a story to demonstrate on a meta-level the power of narrative, is also intended to illustrate the challenges of countertransference in the treatment of patients with severe OCD, and the ways in which a reparative therapeutic alliance can lead to unexpected and vital change.

Introduction

Obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD) is defined for both children and adults in the DSM-IV-TR as follows: (APA, 2000, p. 462) “Either obsessions or compulsions,” with obsessions consisting of recurrent and intrusive thoughts, images or impulses experienced as unwanted or distressing, and compulsions being repetitive behaviours that the person feels driven to do, usually with the aim of reducing distress. The symptoms must either occupy more than one hour per day or cause significant distress or social or occupational impairment. The DSM-IV-TR specifies that children do not need to recognize that the obsessions or compulsions are excessive or unreasonable, whereas adults do. Population-based studies indicate a prevalence of OCD in 2% to 4% of children and adolescents, with a mean age of onset between ages 7.5 years and 12.5 years (AACAP, 2012; Boileau, 2011). Some studies indicate that in OCD affecting children it is more common in boys (3:2), while in adults it is equally common in men and women (AACAP, 2012; Boileau, 2011). The etiology of OCD at all ages is multifactorial, involving a combination of genetic, neurobiological, neurochemical, biological, personality/trait, psychological and social factors. In some cases, infection with group A beta-hemolytic streptococcus can create a syndrome that is indistinguishable from OCD; this is part of a larger group of syndromes known as PANDAS: pediatric autoimmune neurological disorders associated with streptococci (Shulman, 2009). A full review of the etiology is beyond the scope of this paper.

In pediatric and adolescent OCD, the most common obsessions involve religion, sexuality, death or illness, contamination, and over-responsibility for feared harm to self or others or for catastrophic events (Boileau, 2011; Butwicka & Gmitrowics, 2010); the most common compulsions, mean-while, involve cleaning and hoarding (Boileau, 2011). Some research indicates that young children with OCD have associated features of severe indecisiveness, extreme slowness, and excessive doubt about trivial matters (Boileau, 2011). There is some evidence to suggest a higher rate of comorbid obsessive-compulsive personality disorder (OCPD) traits in these children (AACAP, 2012), including a tendency toward rigidity, perfectionism, orderliness, and control. Compared to patients with adult-onset OCD, those who experience onset in childhood are more likely to have comorbid disruptive behaviour, tic disorders, mood disorders, other anxiety disorders, or attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) (Boileau, 2011). Significant to the case featured in this article are several studies that indicate children who have OCD and comorbid major depressive disorder have greater OCD severity, and tend to have higher levels of family conflict (Boileau, 2011). Also relevant to the current case, children with comorbid disruptive behaviour disorders tend to have greater severity of symptoms, greater levels of family accommodation, more treatment resistance, and are 3.6 times more likely to be prescribed atypical antipsychotics than those without concomitant behavior dysfunction (Storch, Lewin, Geffken, Morgan, & Murphy, 2010).

Obsessive-compulsive disorder can have a significant impact on functioning, both at home and at school. The 2012 American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry (AACAP) OCD treatment guidelines cites peer problems in 55% to 100% of patients, and isolation and current or future unemployment at 45% (AACAP, 2012). The World Health Organization recently stated that OCD (regardless of age group) is the tenth leading cause of disability worldwide (Gilbert & Maalouf, 2008). In addition, OCD in childhood tends to be chronic, with 41% to 60% of children remaining symptomatic into adulthood (Boileau, 2011). Predictors of chronicity include the presence of other psychiatric comorbidities and poor initial treatment response (AACAP, 2012), and also possibly the need for hospitalization (Boileau, 2011). The most commonly studied treatment modalities include cognitive-behavioural therapy (CBT), medication management (primarily with serotonin-specific reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs), and atypical antipsychotic augmentation), or combined medication and CBT.

However, CBT, medication, or combinations therein often do not result in full remission (Boileau, 2011; Leib, 2001). Given this, and the high side-effect burden of the medications used to treat OCD, it is crucial that we continue to explore the potential of broader and more integrated treatments for children as well as adults. The vast majority of contemporary evidence-based research on psychotherapy in children and adolescents with OCD involves cognitive-behavioural therapy exclusively (In-Albon & Schneider, 2007; McGehee, 2005; Storch, Mariaskin, & Murphy, 2009), and the majority of nonbiological theories about the etiology of OCD, such as learning theory, are related to the cognitive-behavioural model (Kempke & Luyton, 2007). Of great concern is that many CBT experts bluntly dismiss psychodynamic theory with regards to OCD, and state that psychoanalytic techniques have no place in its treatment (Foa, 2010; British Psychological Society/NICE, 2006). Furthermore, there is disappointingly little contemporary published research on psychoanalytic approaches to pediatric and adolescent OCD (Cohen, 2011), although authors allude to the fact that therapists use these approaches quite commonly in this population (Fonagy, 1999; Quinn, 2010). Some authors argue that there is significant overlap between cognitive-behavioural and psychodynamic theories of OCD, and that the techniques, at least for adults, can be merged successfully in treatment (Kempke & Luyten, 2007).

My intention in this paper is to add support to the evidence base for the integration of psychodynamic and other therapeutic modalities in the contemporary treatment of children, adolescents, and even adults, with OCD. In a society that increasingly favours short-term and psychopharmacological treatment strategies, the richness that these other modalities contribute to treatment may well be lost; furthermore, adolescents like the one described in this paper may all too often be deemed treatment refractory and may be heavily medicated or institutionalized when CBT and first-line medications do not lead to remission. The case study described in this paper illustrates the ways in which psychodynamic, narrative, existential, and metaphor therapy enhance the use of CBT and medication management. It also demonstrates the necessity of complex interventions in the case of an illness as multifaceted as OCD, and the indisputable fact that even young children and adolescents can struggle with sophisticated psychodynamic conflicts. The paper begins with a summary of the patient’s history, followed by a description of the use of conventional therapies. Following this is a discussion of key aspects of different theoretical frameworks, and the ways in which incorporating these frameworks enriched and enhanced the clinical outcome in this particular case. I will argue that had we not employed psychodynamic and other approaches, this patient would likely not have engaged in CBT at all, nor would she have achieved such a meaningful recovery.

Introduction to the Case

I will refer to the patient as “Cassandra,” the name of the fictional character she created during the narrative component of psychotherapy. Cassandra was a 12-year-old in middle school, living in a suburban house with her two parents and one younger sister. Her parents, European in origin, described a generally happy marriage, and were supportive and loving. They were financially stable, with extended family living nearby. Her father worked, and her mother was a homemaker. Although there was no family history of OCD, Cassandra had a paternal grandmother with severe major depressive disorder who had attempted suicide and survived. Cassandra’s medical history was unremarkable, except for pneumonia at age 10 years. She had recently begun menstruating, with regular cycles. She had no known history of streptococcal infection. She also had no history of tics, ADHD, or other diagnosed psychiatric or medical comorbidities. Although she did not meet criteria for a disruptive behaviour disorder, she was described by her parents at baseline as quite “oppositional,” controlling, and perfectionistic.

Cassandra developed OCD six months prior to her hospital admission, when the family had moved to her maternal grandmother’s house while their own home was renovated. Her first symptoms included prolonged and repetitive ordering and re-ordering of shoes by the front door, refusal to empty her backpack or to discard numerous useless items, such as store tags and shopping bags, and a gradual decreasing attention to her own hygiene. Furthermore, she had become increasingly angry with her grandmother, with whom she eventually refused to associate altogether. She developed contamination obsessions and compulsions about her grandmother, and began also to avoid food, clothing, toys, furniture, and other items that her grandmother may have touched. She began to refuse any food that was even remotely associated with her grandmother, and then with her other family members, and her parents had to take her out to restaurants or buy prepackaged food in her presence, in order to get her to eat. She began losing weight. She developed elaborate rituals around the staircase at home, taking up to two hours to get up the stairs, and completing a number of rituals on each step. If her parents so much as moved or breathed audibly during her ascent, she would have to start again at the beginning. Her parents and sister, uncertain of how to cope with this, accommodated and tried to be as quiet as possible during the staircase rituals; each time they accommodated further, however, Cassandra’s symptoms worsened. She developed compulsions in the car as well, requiring that the radio be on at all times and that the windows remain open even in mid-winter. She was afraid to inhale the car air, which she believed was tainted by her parents’ association with her grandmother. She became increasingly (and constantly) distressed and her hygiene deteriorated further, as she refused to shower or change her clothes. She became unable to hide her rituals from her friends, and she was eventually unable to attend school.

By the mid-winter, her illness was so severe her parents brought her to a community hospital, and though she had a three-week admission, she did not receive any specific treatment for OCD. The inpatient psychiatrist suggested aripiprazole, but Cassandra and her parents refused because they were concerned about side effects. Following the admission, Cassandra saw a psychologist for three CBT sessions, but the therapeutic alliance was quite poor. Within the next month, Cassandra further deteriorated, and began refusing to enter the front door of her house. On a particularly cold night, she was unable to enter the house at all, and resisted her parents’ desperate attempts to carry her in, until she urinated in her clothes on the doorstep. Once in the house she begged her mother to kill her with a kitchen knife; her parents managed to force her into the car, and drove her to a downtown hospital. On the way there, Cassandra attempted to exit the moving car on a busy street, and her parents restrained her. She was assessed in the emergency room and then rerouted to our community hospital, where we admitted her to our child and adolescent inpatient unit. Of note is that during the initial interview, Cassandra and her parents denied any significant history of other anxiety disorders, depression, or other psychiatric comorbidities; however, given that she presented with suicidal ideation and a history of social withdrawal, irritability, mood lability, anhedonia, weight loss and insomnia, we suspected that she was suffering from a major depressive episode of several months’ duration. On initial presentation, she was very thin, pale, and significantly malodourous, and she appeared older than her stated age. She was furious with her parents and highly guarded, hostile, and reluctant to engage on interview, often refusing to speak. When she did speak, everyone was struck by her adult vocabulary, her tenacious and complex arguments, and her lack of warmth.

Stabilization, Treatment Structure, and Medication Management

Our primary goal was to ensure that Cassandra was medically stable. A physical exam, a full blood-work panel, titres for streptococcal antigens, and a CT head scan were all normal. Fortunately, Cassandra ate well because the food we provided had not come into contact with her family. As per the AACAP OCD treatment guidelines, we proposed a combination of medication management and CBT. Cassandra adamantly refused medication and became hostile toward my supervisor for insisting upon it. She was willing to begin CBT, however, and so we began CBT prior to the initiation of an SSRI. She was well-versed on the side effects and risks of the different medications, and argued her case with the manner and understanding of a much older adolescent. There were many painfully lengthy negotiations with her, regarding the type of medication (SSRI versus atypical antipsychotic), dosing, and dosage form (liquid versus capsule versus pill), all of which she refused. My supervisor believed Cassandra was incapable of making decisions with respect to treatment, and as per provincial law for adolescents age 12 and older, Cassandra was allowed to contest this finding with the help of a lawyer. At this point my supervisor and I discussed which of us would be involved in the legal review board hearing, as thus far Cassandra had clearly employed the defense mechanism of splitting, such that my supervisor was “all bad” and I was “all good.” My supervisor proposed that we use the splitting to our advantage, and she advocated for a finding of incapacity during the review board, whereas I was completely uninvolved in the hearing and continued treating Cassandra with daily CBT. Cassandra was found incapable with respect to antidepressant but not antipsychotic treatment, and therefore we ordered fluoxetine, beginning at 10 mg daily. Only when we had security officers accompany us to unit with the threat of holding her down while we inserted a nasogastric tube did Cassandra agree to swallow the fluoxetine. Security officers were required to be present for the first few days. Over several weeks the dosage was titrated upward to 30 mg daily. Cassandra’s mood gradually improved, as did her self-care, appetite, and willingness to attend to hygiene, and she began coming to the nursing station to request her medication, saying she felt it was helping. She denied any side effects. The psychotherapies described below occurred in parallel with the medication management.

As Cassandra herself often pointed out, she was a “complicated person” with a complicated illness, whose treatment was, in parallel, complicated. Although I will describe different aspects of her treatment under separate headings, it is important to note that these facets of treatment occurred simultaneously.

Psychotherapy for OCD: CBT Component

Although this paper intends to demonstrate the importance of an eclectic and unconventional approach to OCD, we will still begin with a discussion of CBT and the ways in which it was applied to Cassandra, because CBT was a constant part of her treatment. I would like to emphasise that many of the gains Cassandra made in CBT occurred after interventions that were more psychodynamic in nature, and this will be made apparent below. Numerous sources suggest that the effects of CBT are longer-lasting than those of medication alone (Jenike, 2004; Storch et al., 2007). Cognitive-behavioural therapy is the first-line treatment in children or adolescents with mild to moderate OCD, whereas combined CBT and medication is recommended for those with moderate to severe OCD, or for those with poor insight or cognitive deficits that would interfere with CBT (AACAP). A review of the National Institute for Mental Health data on CBT for OCD describes several meta-analyses that clearly support the use of CBT in children and adolescents (Munoz-Solomando, Kendall, & Whittington, 2008). The most effective form of CBT for OCD is known as exposure and response prevention (ERP) (Foa, 2010; Jenike, 2004), which involves gradual and systematic exposures, along a hierarchy of increasing subjective units of distress (SUDS), to the feared objects or situations. The patient’s usual response (compulsion, ritual, or avoidance) is prevented during exposures. Each exposure must be continued until the SUDS score drops by 50% to facilitate habituation, so that anxiety-provoking stimuli are eventually perceived as neutral. Often relaxation techniques are taught in conjunction with ERP. Exposure and response prevention is primarily a behavioural therapy, but can be combined with CBT when there is a significant cognitive component to the OCD, so that distorted thoughts are targeted along with maladaptive behaviours. There is also some evidence that intensive inpatient CBT involving 15 90-minute sessions spread over three weeks and including a family component, may confer a shorter time to treatment response than once-weekly outpatient CBT in children and adolescents (Storch et al., 2007).

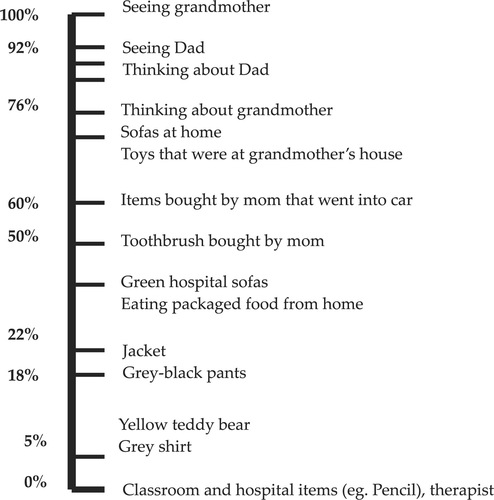

The Ickiness Hierarchy

We began CBT with Cassandra by providing psychoeducation about the etiology, diagnosis, and treatment of OCD, and about the process of CBT. Given Cassandra’s frustration at being referred to as “only a 12-year-old” by many adults, when she clearly was unusually intelligent, I felt it crucial to deliver this psychoeducation in adult terms. She was receptive and easily able to develop a sophisticated understanding of her disorder. She was also able to understand the concept of negative reinforcement as it applied to her OCD: namely, that when avoiding a “contaminated” object or place, she would feel relief, which would then perpetuate avoidant behaviours. She began to understand how her family’s accommodation to her rituals had contributed to her deterioration. We then developed an “ickiness” hierarchy, which was to be the first of many. A brief note on the term “icky:” Cassandra and I brainstormed to describe her feelings associated with contamination, and she felt “icky” was the most fitting. Other words and terms included “disgusting,” “repulsive,” “worse-than-gross,” and “slippery green slime and slugs, and snails, all over everything.” Cassandra greatly enjoyed the process of creating hierarchies, and especially the process of rating “ickiness” scores for SUDS; she had a quirky sense of humour, and would often rate extremely specific scores, such as 92.56%, on the hierarchies. Please see Figure 1 for an example of her first hierarchy. In the end we developed three hierarchies: one for general “ickiness,” one for “repulsiveness” associated with her family, and another for her home and car. The angrier Cassandra was at a person, the higher up that individual appeared on her hierarchies. Although we expected her grandmother to be ranked at 100%, her father was, in fact, equally distressing to her.

Figure 1. “ICKINESS” HIERARCHY

The first exposure involved Cassandra’s grey shirt, which had been brought from home after undergoing five rounds in the laundry, but which was associated with her grandmother. Cassandra wanted to do this exposure alone, and so after rating her SUDS score, I left her, with an expression on her face that demonstrated her aversion to the “icky” item, in her hospital room with the shirt on her lap. By the time I had returned 20 minutes later, Cassandra’s SUDS score had dropped significantly. We worked with this shirt for two days, and then progressed to exposure to her yellow teddy bear, and treatment proceeded stepwise up the hierarchy for weeks. On the days I was not there, the nursing staff conducted exposures with her, though she often refused to cooperate, side-stepped the exposures, or added an unexpected complication. One such complication was that at times Cassandra’s SUDS score would drop dramatically within seconds, and none of us understood whether or not she was being truthful. In the hopes of improving consistency in exposure exercises across staff members, the unit psychologist provided the team with an educational session about OCD and the use of ERP, which proved to be quite useful. The unusual nature of Cassandra’s response patterns to certain exposures may have been attributable to some of the psychodynamic factors described below.

As we progressed up the hierarchies, some creativity was required. After Cassandra began to look at photographs of her family, then of her father, we wanted to start preparing her to return home. She had not been home at this point for nearly three months. Given that the house and car were near the top of her “icky” hierarchy, we decided on a car visit, and then home visit. The goal of this exposure was to arrive in her driveway, with the idea that we would conduct a second visit in which she would then exit the car and hopefully enter the house. During the 40-minute drive, I sat with Cassandra in the back seat and we conducted extensive car-related ERP. Upon arrival in the driveway to her home, she refused to look out the car windows at her mother and sister who were waiting for her. Her mother and sister went into the house, and Cassandra eventually opened the car door and gingerly placed her foot on the ground. Suddenly, as per her usual unpredictable nature, Cassandra jumped out of the car and ran onto the lawn. Without hesitation she continued through the front door and into the kitchen, where she proceeded to open the refrigerator and drink juice. She climbed up the stairs to her room, again unhesitatingly. It was a very powerful moment for her mother, who tearfully watched from the kitchen. We were all surprised that Cassandra had not ritualized at all in the doorway, on the stairs, or elsewhere. When it was time to return to the hospital, Cassandra was actually reluctant to leave.

On her first pass home, she asked to stay overnight. I later discovered the reason for this stemmed from my challenging her by saying “I don’t believe you,” when she had told me that spending time at home would be easy. Following this overnight stay, she progressed to a few weekend passes, after which she was ready to be discharged. Ironically, she resisted discharge, but the timing of her discharge with the end of my rotation at the hospital provided her with an incentive to follow through, which she did. I conducted a telephone interview two months later, and for the first time in our work together, she sounded (as best I can describe) like a “normal” 12-year-old. No more sophisticated arguments or existential turmoil; instead she told me about her plans for the day, her schoolwork, a recent donation she had made, and some extracurricular activities.

In her last few weeks of treatment, Cassandra confessed to an obsession that she had kept secret all along. After one of our discussions about mortality, she told me: “If I don’t pay attention to the sun setting, it won’t rise the next morning.” She and I grappled with the gravity of this idea, and the immense weight of responsibility on her shoulders; indeed, no one would survive, if Cassandra did not pay attention to the sun setting! After considering this belief very seriously, I paused, and said rather lightly, “But that’s not logical,” and she agreed. After this, her insomnia slowly resolved, and when I followed up with her about this obsession, she dismissed it, and waving her hand, playfully said: “Whatevs.”

When CBT Alone Does Not Suffice: Psychodynamic Component

Although Cassandra’s progress with CBT was remarkable, it would not have been possible without the other integrated components of treatment. Following a summary of key psychoanalytic theories about OCD, I will describe some crucial turning points in the therapy that were clearly attributable to psychodynamic and other interventions.

Numerous psychodynamic theories exist about the etiology of OCD, ranging from Freud’s hypothesis that the symptoms constitute a defense against unacceptable aggressive or sexual drives or fantasies (Freud, 1909; Freud, 1966; Gabbard, 2005; Moritz, Kempke, Luyten, Randjbar, & Jelinek, 2011; Sadock, 2007), to later theories about complex family dynamics, developmental trauma (Gabbard, 2005), and maladaptive attachment styles (Doron et al., 2012). The defense mechanisms found most commonly in OCD include denial, indecision, regression, magical thinking, intellectualization, rationalization, isolation, reaction formation, repression, and undoing (Chlebowski & Gregory, 2009; Freud, 1966). Some theorize that in OCD a particularly severe superego, in combination with strong aggressive impulses, results in extreme repression of the impulses (Freud, 1966) that are channeled into obsessions and compulsive symptoms (Kempke & Luyten, 2007). Anna Freud (1966) also posited that in OCD, the ego matures faster than the drives, and that the ego and superego are too advanced at too early a stage, such that they cannot adapt to the drives in a healthy way. This theory may well apply to Cassandra, given her unusual intelligence and the early development of her verbal, moral, and analytical skills. Other psychodynamic factors discussed in the literature on pediatric and adult OCD include: hyperresponsibility, control, shame, loss, relational discord (Gabbard, 2005), anger, and disgust (Allen, Abbott, & Rapee, 2006; Radomsky, Ashbaugh, & Gelfand, 2007). In his famous case of the Rat Man, Freud (1909) hypothesized that the fears in obsessional neurosis correspond to repressed unacceptable wishes, and that obsessional patients intellectualize as a means of consciously accounting for unconscious processes, such as the coexistence of intense love and hate toward the same individual. Interestingly, and highly pertinent to the case of Cassandra, Freud also pointed out that patients with severe obsessions cannot be treated in a simplistic manner.

Further evidence of the role psychodynamic factors play in OCD appears in the form of case reports: Chlebowski and Gregory (2009) describe a series of adult cases in which certain psychodynamic interpretations, mainly about displacement of affect, led to a significant reduction in obsessions and compulsions. McGehee (2005) illustrates the successful purely psychoanalytic treatment of a ten-year-old boy with OCD: in four sessions per week, over the span of two years, an intensive focus on transference allowed the patient to work through numerous obsessional symptoms and achieve long-lasting remission. The author passionately argues for the reintroduction of psychoanalytic thought into contemporary treatment of OCD. Dr. Peter Fonagy presents a compelling case study of a young man named Glen, with severe OCD (Fonagy, 1999). Glen, age 15, acted on compulsions during every waking hour, and after three years of psychoanalytic treatment, his symptoms remitted. Dr. Prudence Leib (2001) presents another fascinating case study, of a woman in her late twenties who refused to accept CBT until her therapist engaged with her in two years of psychoanalysis. Dr. Leib reports that it was only when this patient felt her distress and its origins to be adequately understood, that she was willing to consider changing her behaviours; then the CBT was highly effective, and most of her symptoms, like Glen’s, remitted. (A similar process occurred with Cassandra, as described below.) The authors of a series of cases specific to childhood OCD (Ierodiakonou & Ierodiakonou-Benou, 1997) also argue that a psychoanalytic approach is often essential. Although one larger study (Maina, Rigardetto, Piat, & Borgetto, 2010) reported no additional benefit of adding brief dynamic therapy to SSRI treatment in children with OCD, this study was seriously limited, given the lack of other comparison groups, and because it did not examine the potential effects of adding brief dynamic therapy to CBT, or even to multimodal treatment.

Psychoanalysis and Cassandra

Many of Cassandra’s symptoms are best viewed through a psychoanalytic lens, and it is clear that the psychodynamic components of therapy fostered crucial turning points in Cassandra’s recovery. Certainly, Cassandra exemplified traits described above in the psychoanalytic literature on patients with OCD, such as a particularly powerful superego, and prominent defense mechanisms including intellectualization, rationalization, denial, magical thinking, and isolation. Early on in treatment, Cassandra confided that she believed she was a “terrible person,” which certainly corresponds to Chlebowski and Gregory’s (2009) formulation that “the patient feels threatened by thoughts that he or she is bad, imperfect, unreliable, uncontrollable, or immoral, and he or she is unable to integrate these attributions into a coherent self-image” (p. 9). Cassandra provided me with numerous examples of her “terrible-ness,” discussing how selfish and controlling she was at home, how she cheated when playing games with friends, and how she was mean to her sister and unaffectionate with her parents. This sense of herself as a bad person may have fuelled her attempts to be “perfect,” as well as to be “right” about everything. These compensatory strategies are in keeping with the psychoanalytic theory that perfectionism in OCD may be an attempt to counter unwanted hostile impulses (Kempke & Luyten, 2007).

Cassandra and I talked at length about what it means to be a “good person.” Merging this discussion with a CBT technique, I suggested that she consider behaving as she would imagine a “good person” to behave, and she generated several ideas, including reducing her time in the shower, asking her mother how she was feeling, using recycled paper, and perhaps becoming a vegetarian. During the follow-up interview months after therapy, she told me that she had donated money to a charity, remembering these discussions on the unit. Viewed through a psychoanalytic lens, Cassandra’s lack of warmth, noted upon our initial evaluation, supports Freud’s (1909) hypothesis that resistance in obsessional patients takes the form of indifference toward loved ones. As Cassandra relaxed into the therapy, and as her defenses lowered, she displayed an increasing range of emotions in the presence of her family and staff; on her last day working with me I was both taken aback and touched by her request for a hug goodbye.

Midway through our work together, Cassandra revealed that she was furious with her father for allowing the renovation (and resultant move) and the destruction of her trees in the back yard. She also eventually confided that she was angry with her father for being, as she saw it, emotionally unfaithful to her mother. Although the verity of these claims cannot be confirmed, one remarkable change was that she only agreed to see her father and to conduct exposures around him and the rest of her family after expressing her outrage at him. Interestingly, Cassandra’s expressed hatred toward her father is congruent with Freud’s theory (1909) that in OCD there is aggression particularly directed at the father. Cassandra’s intense anger toward her father, whom she also loved, resonates with the psychodynamic formulations about the difficulties obsessional patients have in tolerating ambivalent emotions toward their loved ones. Her overwhelming anger at her parents resulted in particular compulsions (such as refusing to eat or repeating two-hour long staircase rituals each time they breathed or moved audibly) that controlled and distressed them, and that severely disrupted their lives. One may conjecture that the ultimate expression of this aggression was Cassandra’s plea to her mother to kill her own daughter with a kitchen knife; that said, I felt that Cassandra’s suicidal wish was more likely born of a genuine sense of hopelessness about her situation.

Existential and Metaphor Therapy

The literature on existential psychotherapy and metaphor therapy for OCD in children and adolescents is sparse. Nonetheless, glimpses of these approaches to therapy in children are apparent in many of the above studies, as well as in various textbooks on psychotherapy (Luepnitz, 2002). One could argue that metaphors and existential themes are common to most therapies (Yalom, 1980), but that their use is not generally made explicit. There is one paper that examines the use of existential psychotherapy with children, focusing on issues of freedom and personal choice (Quinn, 2010). The author argues that an existential approach, which comprises working through concepts of freedom, responsibility, death, meaning and meaninglessness, and isolation, is highly relevant for children with mental illness. She points out that existential themes appear almost ubiquitously in the use of metaphor and play. She also posits that an existential therapeutic stance fosters a crucial “relatedness” between child and therapist, providing a safe space in which children can understand themselves more fully, and in which they can then come to terms with the world around them. She notes that this is especially important for children who are critical thinkers, and who are highly perceptive about existential realities, given that often adults disavow these perceptions. Cassandra certainly fit into this category. Quinn also highlights the essential role existential themes and metaphorical play have in consolidating a trusting therapeutic alliance; these factors were, again, essential in our work with Cassandra. Some theorists argue that it is in fact impossible to conduct therapy without metaphors (Barker, 1985; Siegelman, 1990), and that the use of metaphors is linked to narrative and is especially crucial to psychotherapy in children (DeSocio, 2005; Quinn, 2010). Like narrative, metaphors facilitate the creation of a mutual reality; furthermore, metaphors allow patients and therapists to communicate sophisticated ideas using accessible and simple language, which is invaluable when working with children.

Contemplating Existence and Metaphors with Cassandra

Woven through the CBT and dynamic therapy with Cassandra were many existential themes. She described a paralyzing fear that she was “wasting time,” both in terms of wasting her childhood and of wasting her life. She worried that it was “already too late to do something important with [her] life.” She also described her mother as becoming “unkempt,” and had begun to worry over the past few years about her mother aging and dying, and in turn, Cassandra worried about her own mortality. Cassandra reported a fear of aging beginning when she was eight, and as her 13th birthday approached, this anxiety began to heighten. She had an intense ambivalence about attending her grandmother’s 102nd birthday: she feared missing what could be her grandmother’s last birthday, but also feared witnessing her grandmother’s aging. After voicing her fears, she did attend and it was a success. When she had disclosed the above fears to others, she had been told not to be “silly,” and that she was only 12 years old and shouldn’t worry about such things; these responses had then increased her anxiety and sense of isolation. She seemed relieved to be able to discuss these fears with me, and in fact I used these existential discussions as a reward for doing her CBT homework. This was a very effective strategy.

Given Cassandra’s vivid imagination, and the importance of metaphors in creating a shared reality and envisioning a different future, it only made sense to play with metaphors during therapy. One of the first metaphors we used was regarding the process of CBT itself: Cassandra likened CBT to “putting on sunglasses” in order to control what one chooses to see, or think. Another useful metaphor arose when we discussed the benefits and risks of perfectionism. Cassandra recalled the story of Icarus and told me that “if you try to be perfect, you can be burned, your wings can melt.” Cassandra created several metaphors for herself, as well. She first said, “I am like Pandora’s box: all the evils of the world come out, and the only good thing is a tiny little bit of hope.” Also early on in the therapy, she said, “I am like the Arctic tundra: barren, freezing cold, not many can survive it.” When I asked her about this metaphor again several weeks later, after we had further grappled with her sense of herself as a terrible person, she said, “In the springtime, there are rabbits and a few beautiful flowers that grow.” It was inspirational to watch her inner landscape evolve, from one rife with evils, and from a state of barrenness, to one symbolic of greenness, life, and hope. When I asked her explicitly about metaphors for hope at the end of our work together, she said the following: “Just because you can’t see the sun doesn’t mean it’s not shining.” This beautiful metaphor remains with me, and I have shared it with many subsequent patients in times of hopelessness. Watching Cassandra’s metaphors change as the therapy progressed, and the mutuality of playing with the symbolism together, was an unforgettable experience.

Narrative Therapy

The literature on narrative therapy for any age group is also relatively sparse, and interestingly, better-developed in the field of nursing, rather than in general medicine or psychiatry. Narrative therapy is based on the philosophy that language reflects a social construction of reality, and that mentally ill children, adolescents, and adults hold within themselves life narratives that reinforce their painful beliefs about themselves, the world, and others (DeSocio, 2005). Weaving together a new, more understanding, and more forgiving shared narrative in psychotherapy can lead to the creation of a more positive projection of the future (Bennett, 2008). Relevant to the present case study, DeSocio (2005) points out that the upheavals of social and cognitive identity in adolescence provide a unique window of opportunity in which narrative therapy can positively influence the construction of an adolescent’s life story. Bennett (2008) argues that dominant narratives imposed by parents and institutions too often leave a child feeling powerless, whereas creating her own narrative provides a sense of agency. Bennett also capitalizes on the fact that children, whose imaginations remain relatively unfettered in comparison to adults, make ideal candidates for a narrative approach.

It may be no coincidence that our patient named her protagonist Cassandra. She was fascinated by Greek mythology, in which there was a priestess by the name of Cassandra to whom Apollo bestowed the gift of foreseeing the future. When the Greek Cassandra later refused Apollo’s love, he cursed her in anger, ensuring that though she would continue to see the future with stunning clarity (for example, some stories state that she warned her people against accepting the Trojan Horse), she would forevermore be disbelieved (Hamilton, 1999). Various accounts of Greek mythology depict Cassandra as unusually beautiful, charming, astute, and intelligent; nonetheless, she was doomed to be perceived as insane no matter how many times her predictions came true (Hamilton, 1999).

Since a primary goal of narrative therapy is to increase an individual’s awareness of the dominant narratives influencing her life, and to challenge those, it made sense to incorporate this approach into Cassandra’s therapy. Cassandra—our patient—faced a “curse” not unlike that of her Greek counterpart. As described previously, her intelligence and insight were so unusual for her age that she was more often than not disbelieved, and her family and the unit staff often disavowed many of her own theories about her illness as the fanciful notions of “just a 12-year-old.” Interestingly, Cassandra was reluctant to create a narrative about herself, saying, “it’s too personal.” This was further impetus to create a fictional character. Therefore, I will refer to our patient as Cassandra, and her character as “C.,” to avoid undue confusion.

Weaving the Narrative

With some encouragement, Cassandra began to weave C.’s story, which evolved over time as we incorporated it into most sessions. At first, C. was “a happy little girl from a happy family, who suddenly developed OCD.” Soon after, C. was “an anxious girl who had a great life, until some things changed, and everything spiralled out of control.” When Cassandra’s defenses lowered further after a few weeks of psychotherapy, she told a very different story: Here, C. was “a 12-year-old girl who always tried to follow the rules and who wanted to be perfect at everything she did.” When C. was three years old, her sister was born and “got away with” being much less rule-abiding, which made C. angry. C. always felt like a “bad person;” she felt she was selfish and unkind, and also that she had to prove she was good by exceeding everyone’s expectations. In grade three, as the story went, C. was given some tests at school, and no one told her what they were for. She was identified as gifted and reluctantly moved to a new school, where she began to worry about achieving “perfectly” academically. At the end of the day, to relieve stress, she would retreat to her favourite trees in the back yard and read for hours. Then, her house underwent renovation and she had to move to her grandmother’s house. No one told her that as part of the construction trees would be cut down. On a visit to the home one day she realized her trees were no longer there, and that was when she began to do other things to relieve her distress, such as organize her shoes in very specific ways, keep everything in her backpack, refuse to change her clothes, act angrily toward her family members, and refuse to talk to her grandmother. Cassandra said that C.’s mother bought a book about OCD, which C. read, and C. then began to “prove her mother right” by performing more of the rituals that the book said children with OCD do. At first C. felt that all these behaviours were “choices,” and were under her control. After some time, though, her “made-up” OCD behaviours worsened, and escalated uncontrollably.

I will highlight the major themes within this third version of the narrative, just as I did when working through it with Cassandra, as these themes illustrate her psychodynamic complexity. It was clear that Cassandra relaxed into the therapy quite markedly after we began working with narrative. She became more forthcoming and at times quite playful during this process, which is in keeping with the above case reports by Fonagy (1999) and Leib (2001). Apparent in this fictional account is, again, Cassandra’s perfectionism. She experienced the very real academic pressures of a gifted program, which further amplified her prior need to exceed others’ expectations. Alongside this is the theme of sibling rivalry, with Cassandra’s frustration that her sister could get away with less “perfect” behaviour. Also apparent are themes of loss of control, in multiple domains: the birth of her sister, the initially unexplained educational tests leading to an identification as gifted, the move to a new school, the move to her grandmother’s house against her will, the construction that led to changes within her house, and the loss of her back-yard tree refuge, among other things. Themes of anger, frustration, self-hatred, and rage kept emerging in different versions of both her fictional and autobiographical accounts. Within this third story also exists an explanation for the breadth and variety of Cassandra’s OCD symptoms, which is in keeping also with Cassandra’s long-standing oppositionality: if we are to believe the story, it seems that she went to great lengths to prove her mother “right” that she had OCD by adopting symptoms that the OCD book described in other children. Furthermore, this story explains the surprising ease with which Cassandra was able to relinquish certain symptoms after exposures that sometimes lasted less than a few seconds, which as above stirred significant perplexity among the team members. Here Cassandra, like her Greek counterpart, struggled with others’ disbelief; through narrative, however, she was able to convey her internal reality, which increased our understanding, in turn strengthening her trust in our ability to help her. Here, then, is a powerful example of the ways in which narrative relates to psychodynamic therapy and the therapeutic alliance.

On the second-last day of our therapy and of her inpatient treatment, Cassandra told me the fourth and final version of C.’s tale. She said that C. was a “pretty average” 12-year-old who was “OK at a lot of things,” but wanted to do “a lot of non-average things in her life.” She was tired of being average. She ended up in hospital, and learned that she is not a “solid person” but is instead evolving. She learned that “feelings are just feelings,” and that she could control them. She learned how to be her “ideal self” by taking the best parts of herself with her and throwing the rest out.

A Note on Team Dynamics and Countertransference

Daily inpatient psychotherapy was not a standard treatment performed on the acute inpatient unit, and it was a challenge to persuade the team we should take this approach with Cassandra. There were concerns about bed availability and the cost effectiveness of a lengthier admission, and more important, about how challenging Cassandra was as a patient. She was quite oppositional and occasionally verbally tormented the unit staff. She often defied the rules; she spent hours arguing for a particular thing and then once it was done, she argued the opposite cause. Many staff members at times threw up their hands in frustration, saying that Cassandra’s OCD was all “behavioural,” meaning that her symptoms were not in fact the result of anxiety. She caused a great deal of strife among team members, and emotions often ran high during team meetings. Her behaviour, and its effect on team dynamics, was consistent with the clinical literature that addresses countertransference and team conflict in the treatment of adolescents and adults with severe OCD, eating disorders, and personality disorders (Bland, Tudor, & Whitehouse, 2007; Whalley, 1994). This literature indicates high levels of miscommunication, distress, burnout, and anger on these multidisciplinary teams, as well as complex power dynamics and role-reversals among treatment providers. Suggestions for management include the following (to which we did try to adhere): frequent team meetings, debriefing, repeated clarification of treatment goals, and psychoeducation that includes having more than one team member present in each interaction to reduce splitting.

It is only fair that since I described the team’s countertransference, I also describe my own. My experience with Cassandra was very different from that of most of the other team members: I looked forward to working with her each day and left most sessions with a sense of progress and accomplishment. Our interactions were almost all positive. I sometimes felt allied with Cassandra, in the sense that I felt opposed and disbelieved by the rest of the team; I experienced powerful self-doubt and a fear that I was grandiose in thinking I could help her because far more experienced clinicians felt hopeless. When I reflect upon this unusual therapeutic alliance, and the ways in which my countertransference differed from that of the others, I can imagine numerous explanations. I was, firstly, fortunate that she developed a positive transference toward me; it was easier to be empathetic toward her, because she treated me with respect. Secondly, I can surmise that the differences were related to my identification with Cassandra in numerous domains. Lastly, as a psychiatric resident, I was an underling of sorts, and as such identified with not only Cassandra, but with other patients as well.

Follow-Up Interview

During the two-month follow-up interview, I was again struck by how much like a “normal” 12 year old Cassandra sounded, and what a contrast this was to her initial presentation. As we had discussed prior to ending therapy on the unit, I was preparing a case presentation about her and she had wanted me to convey certain messages to my colleagues about how to treat patients. I will, therefore, convey these same messages here. The first thing she told me was, “Burn the textbook!” She wanted me to stress that every patient is unique, and that following a textbook approach would not have worked for her. In her words: “… because [the textbook] is not going to cover everything, because every person is different…. people should put trust in the patient occasionally.” She also wanted therapists to know the following: “People are complicated and just that much more complex when they’re not yet sure who they are. So don’t try to figure a person out, but help them to figure out who they are.” Regarding patient-hood, she said: “… they’re not really a patient per se; it’s more like we’re people as well who are having some trouble. You shouldn’t put a label because it’s upsetting. They’re a person. You should say ‘person who’s having trouble.’”

Discussion and Conclusions

The current case study illustrates a highly integrated and multimodal treatment, with a combination of individual and family psychoeducation, and psychotherapy including CBT, ERP, psychodynamic, existential, metaphor, and narrative therapy. Furthermore, the patient benefited because there was a team of nurses, social workers, occupational therapists, psychologists, and psychiatrists, most of whom specialized in child and adolescent psychiatry. Their unique abilities were all incorporated at various points into the treatment. I hope that this case demonstrates the importance of complexity and flexibility in the therapeutic approach, as well as the importance of openness to using different types of psychotherapy when indicated, in a highly intelligent, resistant, and troubled young patient. Furthermore, I take seriously, in this report, the patient’s own belief that the less conventional parts of treatment were “the most important stuff.”

In many ways, the story of Cassandra and her treatment reads like a fairy-tale, and this fascinates me because the experience of working with her also felt quite magical. In treating her, the team as a whole shifted from a position of therapeutic nihilism to one of optimism; in parallel, Cassandra arrived in a state of suicidal despair and then left in one of hopefulness. We assessed Cassandra in a traditional way, and initially proposed a traditional treatment. We adhered to evidence-based treatment guidelines, while responding to her unique needs; however, we allowed for an unusual degree of creativity in treatment, from both a team-based and an individual therapy-based perspective. As a team, we concluded that the non-evidence-based components of the treatment were essential, and we could not imagine that this degree of profound change could have been achieved solely through medication and manualized CBT. That said it is important to recognize that as with all individual case studies, there was no control group, and so it is impossible to infer causality with complete confidence. Our conclusions are also limited because Cassandra and her family elected not to remain in treatment post-admission, and so long-term follow-up data are not available. Furthermore, it is possible that simply of being away from home, in a structured environment, would have led to remission; it is also possible that the CBT or fluoxetine would have been sufficient, or that the positive therapeutic alliance we forged was the main ingredient in her recovery.

The beauty of exploring a case in depth is that it allows for a full appreciation of a patient’s uniqueness, which is not possible in large randomized controlled trials. In this case the art of storytelling provided a valuable chance to consider alternative possibilities and to examine the subtle turning-points in therapy; it allowed us, the therapists, a chance to enter the particularities of an individual’s psyche, and in turn it allowed that individual to feel “seen” and understood as a person in her entirety. I am convinced that had Cassandra not felt recognized in her unique perspective on her illness, her family, and life itself, she would not have undergone this transformation.

The conclusions to this “story” are as follows: OCD is a complex and multifaceted illness, as are the patients it consumes; treatment needs to follow evidence-based guidelines while also remaining flexible and accommodating to each individual; 12-year-olds can be highly intelligent and can provide valuable insights regarding their illnesses and treatment; psychodynamic, narrative, metaphor, and existential therapy do have a role in conjunction with CBT, in treating children and adolescents with OCD, no matter how severe the illness. Finally, I wonder whether it was my inexperience that gave me the hubris to attempt such an unconventional treatment with a patient who was deemed treatment-refractory from the start. I would posit that medical and psychotherapy trainees can offer the particular kind of inquisitiveness and creativity that come with naiveté, and it is possible that these ingredients in part led Cassandra’s story to such a hopeful ending.

(2006). Ew Gross! Recognition of disgust by children with obsessive-compulsive disorder. Behaviour Change, 23 (4), 239–249.Crossref, Google Scholar

(1985). Using Metaphors in Psychotherapy. New York: Brunner/Mazel.Google Scholar

(2008). Narrative methods and children. Journal of Child & Adolescent Psychiatric Nursing, 21 (1), 13–23.Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

(2007). Nursing care of inpatients with borderline personality disorder. Perspectives in Psychiatric Care, 43 (4), 204–212.Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

(2011). A review of obsessive-compulsive disorder in children and adolescents. Dialogues in Clinical Neuroscience, 13 (4), 401–411.Medline, Google Scholar

(2011). Symptom clusters in obsessive-compulsive disorder: influence of age and onset. European Journal of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 19, 365–370.Crossref, Google Scholar

(2009). Is a psychodynamic perspective relevant to the clinical management of obsessive-compulsive disorder? American Journal of Psychotherapy, 63 (3), 245–56.Link, Google Scholar

(2011). Does experimental research support psychoanalysis? Journal of Physiology, 105 (4–6), 211–219.Google Scholar

(2005). Accessing self-development through narrative approaches in child and adolescent psychotherapy. Journal of Child & Adolescent Psychiatric Nursing, 18 (2), 53–61.Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

(2012). Adult attachment insecurities are associated with obsessive-compulsive disorder. Psychology and Psychotherapy: Theory, Research and Practice, 85, 163–78.Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

(2010). Cognitive behavioral therapy of obsessive-compulsive disorder. Dialogues in Clinical Neuroscience, 12 (2), 199–207.Medline, Google Scholar

(1999). The transgenerational transmission of holocaust trauma. Attachment and Human Development, 1 (1), 92–114.Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

(1966). Obsessional neurosis: a summary of psychoanalytical views presented at Congress. International Journal of Psychoanalysis, 37, 116–22.Google Scholar

(1909). Notes Upon a Case of Obsessional Neurosis. In Reiff, P. (Editor) (1963). Three Case Histories: Sigmund Freud. New York: Simon & Schuster.Google Scholar

(2005). Psychodynamic Psychiatry in Clinical Practice. Washington: American Psychiatric Publishing. (4th ed.).Google Scholar

(2008). Pediatric obsessive-compulsive disorder: management in primary care. Current Opinion in Pediatrics, 20, 544–550.Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

(1999). Mythology: Timeless Tales of Gods and Heroes. New York: Grand Central Publishing.Google Scholar

Short-term psychoanalytic psychotherapy with obsessive preadolescents. American Journal of Psychotherapy, 51 (4), 569–579.Link, Google Scholar

(2007). Psychotherapy of childhood anxiety disorders. Psychotherapy & Psychosomatics, 76 (1), 15–24.Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

(2004). Obsessive-compulsive disorder. The New England Journal of Medicine, 350, 259–265.Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

(2007). Psychodynamc and cognitive-behavioral approaches of obsessive-compulsive disorder: is it time to work through our ambivalence? Bulletin of the Menninger Clinic, 71 (4), 291–311.Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

(2001). Integrating behavior modification and pharmacotherapy with the psychoanalytic treatment of obsessive-compulsive disorder: a case study. Psychoanalytic Inquiry, 21 (2), 222–241.Crossref, Google Scholar

(2002). Schopenhauer’s Porcupines: Intimacy and Its Dilemmas. (Ch. 2, pp. 66–102). New York: BasicBooks.Google Scholar

(2010). No effect of adding brief dynamic therapy in the treatment of obsessive-compulsive disorder with concurrent major depression. Psychotherapy & Psychosomatics, 79 (5), 295–302.Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

(2005). Child psychoanalysis and obsessive-compulsive symptoms: the treatment of a ten-year-old boy. Journal of the American Psychoanalytic Association, 53 (1), 213–37.Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

(2011). Was Freud partly right on obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD)? Investigation of latent aggression in OCD. Psychiatry Research, 187, 180–184.Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

(2008). Cognitive behavioral therapy for children and adolescents. Current Opinion in Psychiatry, 21, 332–337.Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

(2010). The right to choose: existential phenomenological psychotherapy with primary school-aged children. Counselling Psychology Review, 25 (1), 41–48.Google Scholar

(2007). Relationships between anger, symptoms, and cognitive factors in OCD checkers. Behaviour Research & Therapy, 45, 2712–2725.Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

(2007). Synopsis of Psychiatry. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 1270–1273.Google Scholar

(2009). Pediatric autoimmune disorders associated with streptococci (PANDAS): update. Current Opinion in Pediatrics, 21, 127–130.Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

(1990). Metaphor & Meaning in Psychotherapy. New York: Guilford Press.Google Scholar

(2007). Family-based cognitive-behavioral therapy for pediatric obsessive-compulsive disorder: comparison of intensive and weekly approaches. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 46 (4), 469–478.Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

(2010). The role of comorbid disruptive behavior in the clinical expression of pediatric obsessive-compulsive disorder. Behaviour Research & Therapy, 48 (12), 1204–1210.Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

(2009). Psychotherapyfor obsessive-compulsive disorder. Current Psychiatry Reports, 11, 296–301.Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

(1994). Team approach to working with transference and countertransference in a pediatric/psychiatric milieu. Issues in Mental Health Nursing, 15 (5), 457–459.Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

(1980). Existential Psychotherapy. New York: BasicBooks.Google Scholar