Interpersonal Psychotherapy for Depressed Adolescents Adapted for Self-injury (IPT-ASI): Rationale, Overview, and Case Summary

Abstract

Non-suicidal self-injury (NSSI), the intentional destruction of one’s own body tissue without the conscious intent to die, is a significant health concern among adolescents, however, there are few psychosocial interventions designed to treat NSSI. The current paper describes an adaptation of Interpersonal Psychotherapy for Depressed Adolescents (IPT-A) to be used with adolescents who have symptoms of depression and are engaging in NSSI. Specifically, we describe the rationale for the adaptations made to IPT-A for self-injury (IPT-ASI), and a case vignette to illustrate the implementation of IPT-ASI. Non-suicidal self-injury is often triggered by interpersonal stressors, and IPT-ASI directly aims to help clients to improve their interpersonal relationships by increasing emotional awareness and understanding, and teaching communication and problem solving skills via supportive and didactic techniques. The case vignette demonstrates the successes and challenges of using IPT-ASI for an adolescent with moderate depression and NSSI behaviors who began treatment with much difficulty expressing her emotions.

Interpersonal Psychotherapy for Depressed Adolescents (IPT-A) is an empirically supported treatment for adolescent depression (Mufson et al., 2004) and has been proven to decrease depressive symptoms and improve interpersonal functioning (Mufson, Weissman, Moreau, & Garfinkel,1999; Mufson, Dorta, Wickramratne, Nomura, Olfson, & Weissman, 2004; Rossello & Bernal, 1999). Interpersonal psychotherapy for depressed adolescents helps teens better negotiate their interpersonal relationships and learn how their relationships are linked to mood and well-being. These tasks are accomplished by increasing emotional awareness and understanding, and teaching communication and problem-solving skills via supportive and didactic techniques. Interpersonal psychotherapy for depressed adolescents has been adapted for use in both individual therapy and group format for preteens and teens with early signs of depression. The current paper describes another adaptation of IPT-A for use with adolescents who have symptoms of depression and engage in non-suicidal self-injury: IPT-A for Self-Injury (IPT-ASI). Specifically, we describe the rationale for IPT-ASI, the adaptations made to IPT-A for self-injury, and a case vignette to illustrate the implementation of IPT-ASI.

Non-suicidal self-injury (NSSI) involves intentional destruction of one’s own body tissue without the conscious intent to die. Common methods of NSSI include cutting and burning one’s skin. In recent years, clinicians and researchers have turned their attention toward NSSI as the rates for this behavior among adolescents and young adults are staggering: Lifetime prevalence estimates among community samples of high school students range from 13.0% to 23.2% (Laye-Gindhu & Schonert-Reichl, 2005; Lloyd-Richardson et al., 2007), indicating that between 2.2 and 4 million high school students have purposefully injured themselves. In addition to the disturbing nature intrinsic to NSSI, adolescents who engage in it are at an increased risk for attempting (and therefore completing) suicide (Jacobson et al., 2008; Lipschitz et al., 1999; Nock et al., 2006).

Despite the significance of this public health problem, Dialectical Behavior Therapy ([DBT]; Linehan, 1993) (a therapy designed for women with Borderline Personality Disorder (BPD) that balances acceptance and change strategies and includes formal skills training in four modules—interpersonal effectiveness, distress tolerance, mindfulness, and emotion regulation), is the only psychosocial intervention that has demonstrated clear efficacy at decreasing self-injurious behaviors ([note: primarily among adults with BPD] Stanley et al., 2007). More recently, small-scale, quasi-experimental research has suggested that DBT-A (DBT adapted for adolescents) may be effective at decreasing NSSI among teenagers (Fleischhaker et al., 2011; McDonnell et al., 2010). Interpersonal Psychotherapy for Depressed Adolescents (Self-Injuring) [IPT-ASI] contains elements that are similar to DBT-A, such as focusing on interpersonal effectiveness skills; however, the interpersonal skills taught in IPT-A are focused on direct communication and problem-solving. In IPT-ASI the theoretical concept of depression and NSSI highlights problematic interpersonal relationships, specifically in communication skills, and how these trigger and sustain symptoms. The treatment strategies assist teens in understanding, expressing, and communicating their emotions within problematic interpersonal. Dialectical behavior therapy and DBT-A target various skills (as noted above) using a theoretical framework grounded in dialectics. We believe that a true strength of IPT-ASI is in its circumscribed focus.

Finally, it should be noted that the treatment described in this article was specifically developed for adolescents who engage in non-suicidal self-injury as opposed to suicidal behaviors. Because the goal of NSSI differs from that of suicidal behaviors, the techniques used in IPT-ASI may not be appropriate or sufficient for treating depressed adolescents engaging in suicidal behaviors.

Rationale for Using IPT-A to Treat NSSI

There are several reasons for choosing to adapt IPT-A for treating people who self-injure including the overlap between NSSI and depression and the fact that NSSI seems to be triggered by interpersonal forces. Although engaging in NSSI is not specific to one psychiatric disorder, and may occur in the absence of another diagnosis, preliminary research suggests that NSSI is most commonly associated with a diagnosis of major depression. Research also indicated that among a community sample of adolescents, those with a diagnosis of a major depressive disorder (MDD) were 8.31 times more likely to have engaged in NSSI than those without MDD (Garrison et al., 1993). In addition in clinical samples of adolescents who have self-injured rates of MDD ranged from 41% to 58% (Jacobson et al., 2008; Kumar et al., 2004; Nock et al., 2006). Further, when depression not otherwise specified (NOS) and dysthymia are included, the rates of a mood disorder among those who engage in NSSI reach between 89% to 100% % (Jacobson et al., 2008; Nock et al., 2006). Anxiety disorders are also common among adolescents who engage in NSSI, but the rates are not as high as for those with mood disorders (Jacobson et al, 2008; Nock et al., 2006).

The causes of depression are not completely known; however, most researchers and clinicians agree that depression manifests when someone with a biological vulnerability experiences a life stressor or several life stressors (e.g., Joiner, Metalsky, Lew, & Klocek, 1999). Interpersonal life stress is common during adolescence and it may play a causal and sustaining role in depression (Allen et al., 2006; Rudolph et al., 2000). Thus, it is not surprising that IPT-A (Mufson et al., 1994; Mufson et al., 1999; Mufson et al., 2004) has demonstrated efficacy in alleviating depressive symptoms in adolescents because the treatment focuses on improving the patient’s interpersonal functioning within significant relationships.

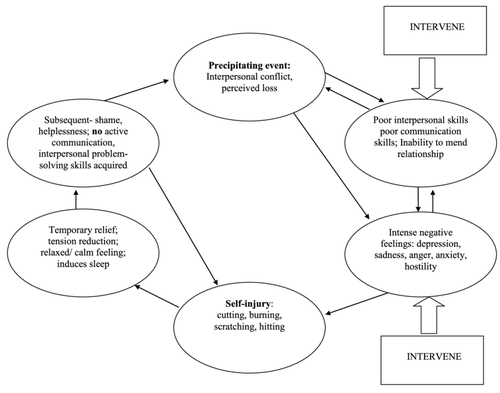

As with depression, the exact causes of NSSI are unknown; however, research shows that NSSI is often precipitated by interpersonal conflict (Guerney & Prinstein, 2007) or anticipated loss (Rosen et al., 1990). The biosocial theory of Borderline Personality Disorder (BPD) has been extended to self-injury, referred to as the Emotional Avoidance Model of Deliberate Self-Harm (Chapman, Gratz, & Brown, 2006). The theory posits that an emotionally provocative event (such as an interpersonal conflict or loss) leads to overwhelming negative affect, which when combined with deficits in emotion regulation, distress tolerance, and a biological predisposition to experience affect intensely, leads to NSSI, which is a temporarily effective coping mechanism. The longer term consequences of self-injury, however, often include shame and helplessness. In the absence of learning interpersonal skills and coping skills, the adolescent remains at risk for subsequent interpersonal conflict and self-injury. Therefore, it is logical that assisting people in coping with loss and improving their interpersonal skills would decrease the extent and intensity of their conflicts and distress, which in turn would decrease their desire to hurt themselves. Figure 1 illustrates NSSI within an interpersonal framework.

Figure 1. NON-SUICIDAL SELF-INJURY WITHIN AN INTERPERSONAL FRAMEWORK.

Empirical research shows the reasons adolescents engage in NSSI (Laye-Gindhu & Schonert-Reichl, 2005; Nixon, Cloutier, & Aggarwal, 2002; Nock & Prinstein, 2004): The most common self-reported reasons for engaging in NSSI are related to affect regulation, specifically the reduction of overwhelming negative affect (Laye-Gindhu & Schonert-Reichl, 2005; Nixon, Cloutier, & Aggarwal, 2002; Nock & Prinstein, 2004). It is likely that the negative affect experienced by the adolescents stems from difficult interpersonal relationships (though this was not specifically assessed in the aforementioned studies). In addition to affect regulation, another commonly reported reason for engaging in NSSI is nonverbal communication with others: For example, among adolescents with a history of NSSI who were admitted to an inpatient hospital, between 65% and 72% endorsed using self-injury to “express frustration” and/or to “express anger/revenge” (Nixon et al., 2002). In another study, 39% of self-injuring adolescents listed anger at their parents as a reason for harming themselves (Laye-Gindhu & Schonert-Reichl, 2005). Therefore, a treatment, such as IPT-A, designed to teach communication and problemsolving skills would likely reduce the frequency of self-injury.

In addition to the theoretical and etiological aspects of NSSI that led us to choose IPT-A for treatment, some fairly practical factors also played roles. First, IPT-A is short-term, ranging from 12 to 15 sessions in 12 to 16 weeks. Second, the focus of IPT-A is fairly circumscribed, addressing interpersonal relationships, rather than numerous foci as other psychosocial interventions (such as DBT) do. Finally, IPT-A has retention rates of up to 75%; (Mufson et al., 1999).

Components and Structure of IPT-A: A Brief Overview

Interpersonal Psychotherapy for Depressed Adolescents is a treatment that uses the therapeutic relationship and didactic techniques to relieve depressive symptoms and improve interpersonal relationships. A brief overview of the components and structure of IPT-A is presented below. For a full description of IPT-A, please see the treatment manual (Mufson et al., 2004). The three primary components of IPT-A are

psycho-education,

affect identification and expression, and

interpersonal skills building.

Psycho-education is integral to treatment; teaching clients about symptoms and rates of depression, the link between mood changes and interpersonal events, and the importance of strong communication skills for good mental health helps them recognize they have a medical disorder, feel less isolated and stigmatized, and more empowered. Affect identification enables adolescents to better understand their emotions, to manage and express those emotions, and to understand how those emotions are reciprocally linked to interpersonal relationships and events. Research shows that teens who self-injure have elevated levels of emotional inexpressivity and avoidant coping compared to teens who do not (Andover et al., 2007; Gratz, 2006); therefore, the teaching component of IPT-A is especially important and relevant for this population. Interpersonal skills building involves didactic techniques, in which the therapist teaches the adolescent (who practices these skills through “work at home” and interpersonal experiments), and the modeling of positive, effective communication techniques with the adolescent.

The 12-to-15 session IPT-A protocol is typically divided into three phases (initial, middle, final). In addition to 12 individual sessions with the client, the therapist has the flexibility to schedule 1 to 3 sessions with the parents as needed.

The initial phase includes confirming and reviewing the depression diagnosis, meeting with parents, providing psycho-education about depression and the limited sick role, completing the interpersonal inventory, identifying the problem area, and reviewing the treatment contract about the focus of the treatment on a problem area (Mufson et al., 2004). The four problem areas in IPT-A are

grief (specifically involving the death of a loved one),

interpersonal role disputes (such as parent-child conflicts),

role transition (such as becoming a big sister/brother or gaining a step

parent), and

interpersonal deficits (leading to or maintaining social isolation).

The goal of the initial phase of treatment is to gain a clear understanding of the client’s interpersonal communication patterns, including strengths and weaknesses, and the relationship difficulty that is linked to the depressed mood so that targets for the remainder of treatment may be determined. The purpose of identifying a specific problem area, which typically involves the client and one other person, is keeping the treatment focus specific to improving that particular relationship. The therapist can then emphasize that skills taught about and practiced in the context of that relationship will be generalizable to other relationships in the adolescent’s life.

Once the problem area is agreed upon, the middle phase of treatment focuses on intervening within the identified problem area through the use of specific techniques including further psycho-education, identification and expression of affect, and interpersonal skills building. Interpersonal skills building is accomplished by modeling the therapist-client relationship for learning interpersonal communication and problem-solving, didactic exercises (such as communication analysis, decision-making practice and in-session role-playing), and practice of these skills outside of the session. The goals of the middle phase include helping the adolescent become more aware of his or her feelings, creating a link between interpersonal events and changes in feelings, and improving interpersonal skills.

The final phase of treatment involves reexamining warning signs of depressive symptoms with the adolescent, reviewing the specific skills learned in treatment and how they can generalize to other relationships and situations, and meeting with parents to review progress and assess need for further treatment. Biweekly continuation sessions or monthly booster sessions are used when appropriate to reinforce skills learned during treatment and to prevent relapse. While the IPT-A model is focused primarily on the adolescent client, parents are included during all phases of treatment: in the initial session for psycho-education, in the middle phase as needed to directly work on communication and problemsolving skills, and during a session in the final phase of treatment to review course of treatment and need for further treatment.

Interpersonal Psychotherapy Adapted for Self-Injury (IPT-ASI)

We chose IPT-A for self-injury because it is targeted and skills-focused, and we wished to amend the existing treatment protocol as little as possible. As all of the techniques included in IPT-A are relevant for IPT-ASI, the changes made were additive (i.e., we did not remove any standing IPT-A techniques) and specific to addressing the self-injurious behaviors. The feasibility of the added components was assessed with five adolescents in open treatment. The specific changes include:

assessment of the nature and severity of NSSI,

psycho-education regarding NSSI, examination of the motivations behind the NSSI, and

increased safety measures.

Each takes place during the initial phase of treatment, is referenced and reviewed during the middle and final phases.

Assessment and Psycho-education

Interpersonal Psychotherapy for Depressed Adolescents places great importance on providing clients with full assessment of depressive symptoms and psycho-education about the nature and course of adolescent depression to convey to the adolescent and parents that depression is a medical illness to be taken seriously. For IPT-ASI, we added a full assessment of NSSI in addition to providing education about the nature and course of NSSI in adolescents and young adults. During the first session, the therapist conducts an assessment of the frequency, types, and severity of the teen’s NSSI behaviors. This assessment includes asking about the onset of the self-injury and the function of the self-injury from the adolescent’s perspective. (It is assumed that the teen’s self awareness regarding the functions of self-injury will increase throughout treatment.) The therapist may choose to use structured assessment tools, such as the Self-injurious Thoughts and Behaviors Interview ([SITBI] Nock, Holmberg, Photos, & Mitchel, 2007), to conduct the assessment. It is extremely important to determine that the client does not engage in self-injury with suicidal intent. Also included in the assessment is the teen’s motivation to stop self-injuring. In order for the IPT-ASI to be effective, some intrinsic motivation to at least decrease the self-injury is helpful.

Once a full assessment of NSSI is completed, the therapist provides education about NSSI to both the teen and his/her parents. (We recommend that the first session be divided into three time slots: meet with teen first, then parent alone, then both together. The first session typically lasts 60 to 90 minutes so that all necessary tasks can be accomplished.) Such education includes providing a definition of NSSI, the types of behaviors included within that definition, the fact that many people engage in NSSI repeatedly, and basic prevalence information. Providing the teen with basic information regarding what is known about why people engage in NSSI can help to decrease a sense of isolation or perception of aberrancy. We also found it useful to provide information regarding the risks associated with engagement in NSSI, especially for teens that may have been forced to come to treatment and need a boost in motivation to stop self-injuring. As the teen (and parent[s]) may find the information provided somewhat overwhelming, we created an information sheet the therapist can distribute based on research related to self-injury called “Non-suicidal self-injury: What is it and why do kids do it?” (Appendix A).

As part of the assessment and psycho-education, the client is asked about any behaviors he or she may engage in that are helpful in resisting the urge to self-injure. If the client has difficulty identifying such behaviors, the therapist may offer suggestions. To facilitate this task, we created a handout “Alternative Behaviors for Coping—ABCs” (Appendix B) that lists example behaviors that may work to either “replace” self-injurious behaviors, such as holding an ice cube, snapping a rubber band, or “soothing and distracting behaviors” such as doing yoga, going for a run, or journaling. (The behaviors listed on the worksheet are drawn from behaviors suggested in other cognitive behavioral and dialectical behavior therapy protocols.) The teen should choose several behaviors he or she thinks may be effective when an urge to self-injure arises. The adolescent is given a copy of the “ABC” and the therapist will refer to it throughout the course of treatment.

The next task of the initial phase is to explain to the client and parent[s] how IPT-ASI helps people to stop self-injuring and how it helps to treat depressive symptoms; this rationale is included on the information sheet (Appendix A). The therapist briefly describes why both depression and self-injury often partially are caused and maintained by difficulties with (or losses of) interpersonal relationships. The therapist goes on to explain that IPT-ASI assists in building their interpersonal skills so that teens can better express their emotions verbally and thereby manage relationships more effectively.

Increased Safety Measures

We felt it was necessary to increase the safety measures taken within the IPT-ASI protocol because of the potentially lethal nature of self-injury. The therapists carry pagers and are on-call “24/7” to handle clinical emergencies only. The teen clients are instructed to page the therapist in the event of strong urges to self-injure, engagement in severe self-injury, and/or the onset of suicidal ideation. During the first session (and throughout treatment), the client is reminded to refer to the ABC handout to try any/all replacement or soothing/distracting behaviors in the event of an urge to self-injure. If self-soothing techniques are ineffective and the urges remain, the adolescent is instructed to contact the therapist. The therapist will discuss the precipitant of the urges to diffuse the emotional intensity that often accompanies NSSI and conduct a decision analysis exercise with the adolescent in which the participant and therapist will brainstorm and choose an alternative behavior to self-injury. If, after this brief intervention, the participant is unable to confirm that he or she will not engage in NSSI, the parent is contacted and informed of the conversation. In addition, the participants and their parents will be given the phone number for their local emergency room.

When the participant pages the therapist following an incident of NSSI, the therapist conducts an evaluation over the phone as to the seriousness of the injury. If the therapist is able to verify that the injury was minimal, the therapist encourages the participant to contact a parent to discuss the injury and obtain support; the therapist also informs the parent of the NSSI espisode. If the therapist is unable to verify that the injury was mild/superficial, the therapist directs the participant to the emergency department and informs the parent[s]. The therapist attempts to keep the interaction with the client brief and focused so as not to reinforce the self-injury by providing attention.

Involvement of Parents

Confidentiality is of utmost concern within IPT-ASI. However, due to the nature of self-injury, there are times when confidentiality must be broken and the parents must be contacted in order to ensure the teen’s safety. In the majority of cases (NSSI behavior, suicidal ideation, intent, etc), it is appropriate that the therapist encourage the participant to discuss his/her feelings and actions with the parent first, but that the therapist must also inform the parent of the suicidal ideation or NSSI to utilize the parent(s) in safety planning, when appropriate. When teens page their therapists due to an urge to self-injure, the therapist does not necessarily contact the parent. Specifically, if the participant is able to confirm that the urge to self-injure has subsided and that s/he will not engage in NSSI, the parent may not be contacted. In the rare cases when a teen engages in very mild NSSI and is adamant that the parent not be contacted, the clinician may honor that request, depending up the policies of the specific treatment setting and the nature of the agreement made with the parents at the start of treatment. Because the issue is very likely to arise during treatment, it is of utmost importance to discuss issues of confidentiality openly with parents and client in the first session.

Monitoring NSSI: Self-injury monitor

One of the first skills taught (typically in the second session) to the adolescent in the IPT-A protocol is how to monitor symptoms of depression and overall mood, with the goal of increasing awareness of the connection between life events and mood. Included in the IPT-ASI is the Self-injury Monitor, which therapists use to help the adolescents indicate the strength of urges to self-injure and the number of times they actually engaged in self-injury over the preceding week. Specifically, the adolescent client is asked to rate average mood from 1 (best ever felt) to 10 (worst ever felt) during the past week. The teen is then asked to rate her worst mood and best mood throughout the week as a way to link mood fluctuations to specific interpersonal events. To remain consistent with the IPT-A protocol, it is useful to have the client rate the average urge to self-injure and then the strongest urge to self-injure over the week. The therapist then focuses on the strongest urge (or incident of self-injury if there was one) and works with the teen to examine events that preceded and followed the NSSI urge and also reviews the safety plan, including the ABC behaviors. In a way that is similar to linking depressive symptoms to life events, monitoring the self-injurious incidents helps the client learn what types of events lead to increased urges to self-injure.

Assessment of Self-injury within Interpersonal Inventory

The final addition made to the IPT-A protocol is the incorporation of the “Interpersonal Inventory,” an assessment in which interpersonal relationships are most closely linked to the teen client’s NSSI. To identify the significant relationships, the therapist uses a visual aid called the “Closeness Circle.” in which the adolescent places the significant people in her life. People are placed closer or farther from the adolescent (in center) according to level of closeness and involvement in the adolescent’s life. The teen is then asked to identify four or five of the people who are most important to know about so that it is possible to better understand the story about his or her depression and NSSI. The teen is then instructed to describe each relationship, including the nature of interactions, positive and negative aspects of the relationship, how the relationship affects depression (and how depression affects the relationship), the things the adolescent would like to change about the relationship to improve mood, and any significant events that have happened in their lives and relationships. In IPT-ASI, the interpersonal inventory proceeds as the therapist asks the teen to examine how each relationship (and the interactions therein) may exacerbate or decrease self-injury.

The middle and final phases of treatment remain consistent with IPT-A. The therapist continues to assess depression and self-injurious symptoms at the beginning of each session and then focuses on affect identification and clarification and skills building. The termination phase of treatment includes reviewing the warning signs for depression as well as triggers for self-injury. The therapist and adolescent client review the strategies practiced during the middle phase and skills learned during treatment, and they discuss how these can be applied to problems that may arise in the future. Finally, the depressive symptoms and NSSI urges and behaviors are fully assessed and if appropriate, referral for continued treatment is made.

Case Illustration

In the following case illustration, we provide a summary of the course of IPT-ASI for an 18-year-old female, Melissa, who had been engaging in NSSI (cutting) for approximately three months prior to starting treatment. Melissa was part of the open trial for IPT-ASI and provided consent to use her treatment for educational purposes, including publication to illustrate the techniques of IPT-ASI. Identifying information and some specific details related to the case have been changed to retain the teen’s anonymity.

Client Description

Melissa was an 18-year-old, single female of mixed racial heritage who resided with her mother and younger sister. With regards to Melissa’s psychosocial history, it became clear that the relationship between her parents was strained since she was a young girl and this was very troublesome to her. Her parents were divorced and her father had remarried and had three children from his second marriage. Melissa and her sister lived primarily with their mother but stayed with their father often and he remained very involved in all aspects of their lives and made many of the decisions regarding their education and social lives.

Melissa was referred to treatment for her NSSI and depressive symptoms by a social worker who was concerned that Melissa needed more specialized care than she was providing. Melissa had started treatment at the local hospital with the social worker after she confided to a teacher that she had been sexually assaulted by an older man she had been dating (identified as J, 32 years old). This man forced Melissa to have sexual intercourse with him after she had refused. Although the assault was upsetting to Melissa, her symptoms worsened significantly after telling her parents she about dating an older man and the assault. Her father reacted with anger and blame (meaning it was her fault that she was assaulted), and her parents insisted on pressing charges (against J), which was stressful and scary for Melissa.

At the time of our meeting, Melissa’s depressive symptoms had wors-ened and her self-injury had increased. After consenting to participate in the IPT-ASI clinical trial, Melissa met with an evaluator. As part of the initial evaluation, Melissa completed the Schedule of Affective Disorders for Children (K-SADS; Chambers et al., 1985) as well as a self-injury interview. During the evaluation, it became clear that Melissa’s depressive symptoms began shortly after the sexual assault incident (approximately three months prior to the evaluation), but worsened more recently. At intake, she was diagnosed with Major Depressive Disorder, moderate (MDD). Melissa reported she had lost many friends as a result of being grounded, her relationship with her father was very strained, and her self-esteem was extremely diminished. Despite the depression, Melissa was performing well in her school work and remained involved in extracurricular activities, including sports, but her performance had declined somewhat.

Melissa began engaging in NSSI after divulging details of the assault to her parents and her father’s angry, blaming reaction. At the time of intake, she had cut 12 times over a three-month period. The cuts, made with a kitchen knife, were superficial and she had no intention of dying. The most recent episode had occurred two weeks prior to her intake appointment. Melissa described that almost every incident of NSSI occurred after a distressing interpersonal event, such as arguing with her mother and father. When asked about her reasons for engaging in NSSI, Melissa spontaneously reported that she engaged in NSSI to punish herself. However, her responses to a structured interview indicated that she also engaged in NSSI to get attention from others and to regulate negative feelings. The frequency and nature of Melissa’s self-injury indicated that she would meet criteria for non-suicidal self-injury disorder (NSSI SI Disorder; Shaffer & Jacobson, 2010), which is being considered for inclusion in DSM V.

It should be noted that Melissa did not meet criteria for Posttraumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD). Although Melissa experienced some symptoms of PTSD (including difficulty sleeping and hypervigilance when in close proximity to the site of the assault), most of her problematic symptoms (irritability, depressed mood, anhedonia, worthlessness, and guilt) appeared more closely linked to the difficulties in her relationship with her parents and friends after disclosing the assault.

Case Conceptualization/Formulation

Melissa was diagnosed with Major Depressive Disorder, moderate, and engagement in NSSI. Melissa’s depressive symptoms and NSSI started after the sexual assault three months prior to intake. The assault greatly affected her already strained relationship with her parents. Although Melissa was upset by the assault, she did not meet criteria for PTSD. She felt the assault was not the main source of her current distress, but her poor relationship with her parents was.

Melissa’s parents, especially her father, reacted to the assault with anger rather than compassion. Her parents chose to punish Melissa and did not provide a supportive environment or encourage open communication. As a result, Melissa internalized feelings of guilt and shame, which left her at risk for depression and NSSI. The negative response by her parents likely affected Melissa so strongly because of the preexisting problems within their relationships. It was clear that she strongly identified with and admired her father, who she described as stoic, very strong, and extremely achievement oriented and hard-working. It appeared that Melissa was determined to model her father’s stoicism and independence. However, it was also clear that though Melissa identified with her father, she often fought with him as he was a very strict disciplinarian and placed unrealistic expectations on his children, demanding that they excel academically and athletically and refrain from any romantic relationships. Melissa’s relationship with her mother was also strained: Melissa perceived her as weak in comparison to her father. However, Melissa admitted she knew her mother loved her strongly, and she admired her mother for being family oriented.

In summary, the assault seemed to have a trifold effect on Melissa’s life:

the fall-out from the assault resulted in a worsening relationship with

her parents,

the loss of a relationship with J, the assailant,

and isolation from her friends because of being grounded.

Melissa’s admiration of stoicism, emotional inexpressiveness and lack of effective communication skills resulted in her failure to look to others for support and nurturance. Consequently, Melissa became depressed and began engaging in NSSI as form of self-punishment, nonverbal communication, and mood regulation.

Because of the clearly interpersonal nature of both the depression and the self-injury, IPT-ASI seemed a good treatment approach for this patient, and Melissa was guardedly hopeful that the treatment would improve her mood and her relationship with her parents. Upon initiation of the IPT-ASI protocol, Melissa ceased treatment with the referring social worker.

Course of Treatment

Initial Phase. The first session in IPT-ASI lasts approximately 75 minutes and several tasks must be completed. The therapist met first with Melissa alone and then with Melissa and her mother together. Melissa was engaged and seemed eager to understand her depression and self-injury and to explore her interpersonal relationships. First the therapist and Melissa reviewed her depressive symptoms using the Children’s Depression Rating Scale (CDRS-R; Poznanski, Freeman, Mokros, 1985). Melissa reported feeling somewhat improved compared to her evaluation because she had some positive interactions with her father and a court date regarding the assault had been postponed. Melissa also reported continued apathy about her friendships, initial insomnia, and decreased appetite. A review of self-injurious thoughts or behaviors during the previous two weeks indicated that Melissa had not engaged in NSSI, nor did she have urges to do so.

The next step was to complete psycho-education about depression and self-injury. Psycho-education about depression included reviewing prevalence rates and common co-occurring difficulties. The idea of the limited sick role was introduced. Specifically, it was explained that because depression and NSSI are serious illnesses that impact functioning, Melissa should not be expected to perform all of her responsibilities at her optimal level while in treatment. For example, Melissa was very involved in sports, and her performance had suffered somewhat since the onset of her depression. Additionally, Melissa was having some difficulty concentrating in class and her grades, though still strong, were not quite as high as usual. However, Melissa was encouraged to do as much as possible with support from her parents and advised that her motivation and performance would improve as her depression remitted.

Using the self-injury information form, Melissa and the therapist discussed why people tend to engage in NSSI as well as risks associated with it. The Alternative Behaviors for Coping (ABC) form was then introduced, and Melissa chose the self-soothing and replacement behaviors she would try if she had an urge to self-injure. During the discussion of the ABCs, it became apparent that Melissa was ambivalent in her motivation to stop self-injury. This is common among teens self-injure. The NSSI serves a function that the teen views as positive. As part of the safety plan, Melissa agreed to alert her mother to urges to self-injure if she did not feel better after trying one of the ABC behaviors.

Melissa’s mother joined in the final part of the first session, and the therapist reviewed important information about depression and NSSI as well as the safety plan. Again, the safety plan included trying one of the behaviors specified on the ABC form, reaching out to her mother, and calling the therapist if no other problem-solving approach was successful.

During the next four sessions, the therapist’s goal was to learn about Melissa’s interpersonal relationships to identify a problem area while continuing to monitor her depression and NSSI. In helping Melissa to begin associating changes in mood to specific events, we asked her to rate her mood from one to ten, with one being the best she ever feels and ten being the worst. Her average mood mostly fell between three and four during the next few weeks, with Melissa reporting spikes of six or eight after having arguments with her mom.

Melissa’s depressive symptoms and NSSI urges and behaviors were reviewed at the start of each session. Melissa reported two episodes of urge to self-injure during the initial phase of treatment. The first urge came after she had an argument with her mother; Melissa began thinking about her poor relationship with her parents and the assault. The second incident was motivated by feelings of wanting attention (i.e. using NSSI to nonverbally communicate her desire to be noticed) from her mother and sister because she was feeling left out of their close relationship with one another. Melissa refrained from engaging in the NSSI because she did not want to get in trouble. Melissa agreed to try one of the self-soothing behaviors identified on her ABC form or reach out to her mother if the urge to self-injure increased again.

As part of the interpersonal inventory, Melissa placed several people on her “closeness circle” and discussed her relationship with her mother, father, sister, and cousin. She described the positive and negative aspects of her relationship with each of these family members, and became tearful when explaining her perception of exclusion by her mother and sister. Not only did Melissa report feeling annoyed by her sister and mother because of their naiveté about Melissa’s social struggles in being of mixed-race heritage and her adolescent struggle with dependency and autonomy issues, but Melissa also was envious of their close relationship and perceived similarity in personalities. It was evident that Melissa had no plans or perceived ability to discuss these feelings with her mother or sister. Melissa also had ambivalent feelings toward her father; she admired his perseverance and stoicism while she disliked his selfishness and aloofness. Melissa and the therapist agreed that she was experiencing an interpersonal role dispute with both of her parents. The dispute was centered on issues of independence, trust, and priorities. The tension around these issues peaked following the sexual assault. Melissa felt she should be given more independence than she was receiving, and she wanted to focus on both her social life and academic pursuits. Subsequent to the assault, her father reverted to treating her like a child, and he insisted that she focus solely on her schooling and athletics. Consequently, Melissa perceived her father as too controlling and punitive and was feeling frustrated about her mother’s inability to successfully advocate for Melissa with her father. Melissa was extremely uncomfortable discussing her feelings of hurt, disappointment, and anger toward her parents and turned to NSSI to cope with those feelings and to get attention from her parents. Their strong negative reaction to NSSI was perceived as a sign of caring by Melissa. Melissa and the therapist identified several treatment goals including to 1) help identify and discuss feelings more comfortably and 2) negotiate privileges with her parents more effectively, in addition to reducing her depressive symptoms and engagement in NSSI.

Middle Phase. Melissa was feeling better at the start of the middle phase of treatment; she attributed this to having had some privileges reinstated by her father, such as getting her cell phone back. She rated her mood between a three and four on the scale of one to ten. However, around the eighth session issues pertinent to the trial arose, which led to an increase in depressive symptoms, increased urges to self-injure, and arguments with her parents. Specifically, Melissa believed she would have to testify about the assault, and she had seen and spoken to J on her own accord. These incidents increased her anxiety and led to arguments with her parents, who had strongly insisted she end the relationship with J and have no more contact with him. Her struggle to separate from her parents was complicated by her relationship with J, which led to significant conflict with her parents regarding their ability to trust her relationship choices and to give her more freedom. Decisions and feelings surrounding the trial and J were the focus of several subsequent sessions. The therapist focused heavily on teaching Melissa to identify, clarify, and express her emotions in session. The therapeutic setting allowed Melissa to practice articulating her feelings in a safe environment, with the goal of Melissa expressing her feelings about difficult issues with her mother and father. Melissa voiced a combination of feelings including relief, anxiety, and excitement around issues related to the trial. Although she thought she had to testify, ultimately she did not have to. She was relieved but also disappointed; part of her wanted to see J again; she missed the relationship they had before the assault.

Melissa continued to experience urges to self-injure following arguments with her mother. She shut down rather than share her feelings. For example, Melissa was unable to articulate her complicated feelings about J with her mother. Melissa felt that her mother was unable to understand how she could still have positive feelings toward J after what he had done to her. This was exacerbated when Melissa’s mother found out Melissa had spoken to J one day on the street. She immediately became angry and forbade Melissa to ever see him. Melissa became irritable and upset when her mother tried to discuss the issue with her.

A communication analysis of a conversation Melissa had with her father exemplified her intense difficulty sharing any negative feelings. Melissa’s father checked in with her about how she was feeling about the assault, including the trial and her feelings about J. Although this was a good opportunity for Melissa to share her feelings with her father, she replied “fine.” The communication analysis revealed that Melissa was intent on appearing strong and stoic to both of her parents and that she was afraid to share her true feelings with her father because he might get upset. However, failing to have her parents understand her feelings left her feeling unsupported and emotionally isolated. Melissa admitted she wished the conversation with her father had been longer and that she had been honest with him regarding her feelings. During that session, she and the therapist brainstormed about how she might broach the topic of the assault with her father in a future conversation. One idea was for Melissa to thank her father for asking her about her feelings so that he knew she was appreciative, which would ideally lead him to asking her more often in the future. Because Melissa was apprehensive about addressing this difficult subject with her father “out of the blue,” she and the therapist also role played how Melissa might ask her father for an “appointment” to have a conversation in the future. Melissa’s feelings surrounding the assault and the trial were varied, intense, and somewhat hard to identify; therefore, the therapist also normalized Melissa’s difficulty about being open and honest with her father. This conversation led to further exploration of Melissa’s feelings, and Melissa was able to clarify that though she enjoyed the positive attention J gave her before the assault, she was angry at him not only for the assault but also for the negative impact the assault had on her relationship with her parents.

Melissa was faced with a difficult decision regarding the assault trial and rather than act impulsively, Melissa and the therapist addressed problem-solving skills by completing a decision analysis. A decision analysis is used to help an adolescent see that there are often multiple solutions to a problem and these need to be identified them when faced with a difficult decision. Possible solutions to the problem are generated (ideally by the adolescent herself, but the therapist may recommend possible solutions as well), the pros and cons of each are weighed, and the teen chooses one solution to enact during the upcoming week. Melissa and the therapist generated a list options, evaluated the advantages and disadvantages of each, and chose what seemed like the best solution to deal with an unpleasant situation. As a result of the decision analysis, Melissa refrained from acting impulsively and did not jeopardize her role in the trial. While a decision analysis often leads to the role play of a discussion about the alternative solution (and trying this encounter between sessions), sometimes a decision analysis results in a client refraining from a behavior that might have negatively impacted the significant relationship.

As the final phase of treatment approached, Melissa recognized the importance of expressing her emotions verbally to decrease her urges to self-injure. She was increasingly able to express her complex feelings about each parent and J and to link arguments with her parents to her increases in depressive symptoms and urges to self-injure. However, her ability to really express and understand her feelings was limited to within therapy sessions, and she remained hesitant to practice expressing herself with either parent. While the ultimate goal of IPT-ASI would be for Melissa to more readily express her feelings with her parents, by this stage she made progress in identifying her own feelings, making links between emotion and events, and implementing problem-solving skills that lead to a decrease in conflicts. Further, throughout the middle phase of treatment Melissa was able to refrain from acting on any urges to self-injure and her depressive symptoms decreased in severity (her BDI score decreased from 33 at intake to 20 at week 8). Because she gained more understanding of her feelings and was able to express them in the safe therapeutic setting, she was not driven to engage in NSSI.

Final Phase. As Melissa began to feel better, reporting fewer symptoms of depression and only one incident of a medium urge to self-injure, she missed two sessions in a row. Therefore, because Melissa wanted to complete the treatment and move on to her summer academic program, we completed the final phase of treatment in one long session. Tasks to be completed in the final phase of treatment include reviewing symptoms and warning signs, reviewing strategies learned in treatment that were helpful to the adolescent, and processing the end of the therapeutic relationship.

Melissa arrived an hour late to our final session and said that she was hesitant to come as she knew we would be saying good bye and discussing the road ahead. The therapist praised her for coming in despite her discomfort. In the symptom review, Melissa denied most symptoms of depression (including crying, feeling down), though she endorsed some anhedonia and continued irritability with her mother, father, and sister. Specifically, her depressive symptoms decreased over time (BDI score decreased from 33 at intake to 18 at week 4 to 20 at week 8 and 5 at week 12). Although she had continued to have urges to self-injure during the middle phase of treatment, those urges decreased in intensity (with the exception of one medium urge following receiving a poor grade in school), and subsided completely during the two weeks prior to our final session. The therapist reviewed the importance of identifying warning signs of depression and upcoming potentially stressful situations (that may increase her depression) so that the recurrence of a major depressive episode and engagement in NSSI could be prevented. Melissa identified specific strategies (including journaling, doing yoga, and listening to her favorite band) that she would try if she noticed an increase in depression or an urge to self-injure. She and the therapist spent a good deal of time reviewing content discussed during their time together, highlighting the importance of identifying and communicating one’s feelings, both with oneself and with others, in order to avoid feeling the need to self-injure and the worsening of depressive symptoms. The therapist noted that she was concerned that Melissa might be vulnerable for depressions and self-injury in the future because she continued to resist directly reaching out to her parents for support. The therapist specifically directed Melissa to try to connect with her parents through more direct communication when feeling somewhat ‘good‘ so that in times of crisis she would feel less threatened and more comfortable in sharing her feelings with them. Again, Melissa agreed with this principle and seemed more comfortable with expressing her feelings in therapy. However, she remained unsure about being able to consistently express her feelings more openly with her parents. Melissa felt that her time in IPT was helpful because she more clearly understood her own feelings and as evidenced by her ability to refrain from engaging in NSSI, she learned that expressing them could be therapeutic. She felt that there were more issues to address but she was not interested in continuing treatment for the monthly booster sessions because she was looking forward to summer vacation, which included travel. The therapist advised Melissa that when she returned from vacation she could call and have booster sessions.

Epilogue. At her six-month visit, Melissa had maintained her treatment gains and continued to improve. She reported she had not engaged in NSSI since completing treatment, and she endorsed only occasional, mildly depressed mood and irritability with her parents, these did not meet criteria for MDD.

Reflections on the Case. Melissa’s case was a difficult one largely due to high level of emotional inexpressiveness in general, and poor communication skills with her parents, in particular. We chose to highlight this case partly because it is quite prototypical of adolescent self-injurers, as research and clinical practice emphasize a lack of emotional acceptance and expression among this group (Andover et al., 2007; Gratz, 2006). Therefore, though the progress made throughout the course of Melissa’s treatment seems modest (she did not master emotional sharing with her parents), her improvement in identifying her own feelings and articulating them in therapy is extremely important in laying the groundwork for her future relationships. Indeed, a primary goal of IPT-ASI is to improve feeling identification (including linking mood to interpersonal events) as well as to increase verbal communications. Still, Melissa did not change her interpersonal behavior as much as would be desired over the course of treatment. Nonetheless, Melissa did not engage in NSSI during the course of IPT-ASI or at follow up, suggesting the skills she learned in treatment about affect identification and expression and problem solving may have assisted her in refraining from self-harm. The fact that Melissa’s course of treatment was only 12 sessions and that there remained a good deal of work to be done suggests the protocol may need to be lengthened for adolescents with comorbid depression and NSSI. Similarly, because we had no comparison treatment condition, it is possible she may have shown these improvements with any type of psychotherapy. Additionally, Melissa’s father did not participate in treatment, which may have been an essential component for them to engage in a positive, emotional exchange.

When reflecting on the changes we made to the original IPT-A protocol to accommodate NSSI as well as depression, it seems that the increase in safety precautions, psycho-education about NSSI, and the Alternative Behaviors for Coping exercise were quite useful. As far as monitoring NSSI—it seems that an overall rating of urges for the previous week was sufficient and daily ratings may not be necessary. Additionally, linking the conceptualization of the depressive symptoms and the NSSI within an interpersonal framework was effective. In sum: At the very least, the experience of treating Melissa, as well as the other adolescents who took part in the open trial of IPT-ASI, suggest that IPT-ASI is a feasible treatment for adolescents with co-morbid depression and non-suicidal self-injury and that further research into the treatment’s effectiveness is warranted.

Appendix A Non-suicidal self-injury: What is it and why do kids do it?

What is Non-suicidal self-injury (NSSI)?

| • | NSSI involves purposefully hurting oneself without wanting to die from the act.1 | ||||

| • | Types of self-injury include cutting, burning, scratching, and hitting oneself. | ||||

| • | Often times people engage in NSSI repetitively, although some kids will just try it once and then not do it again. | ||||

Why do kids engage in NSSI?

| • | The kids who engage in NSSI repetitively do so because they find that it helps them feel something they want to feel. Kids give all different kinds of reasons for wanting to hurt themselves. | ||||

| • | For example, some kids say that after they hurt themselves they feel less stressed or less tense.2 | ||||

| • | Others say it helps them feel “something” when they feel nothing.3 | ||||

| • | Some kids say they engage in NSSI to communicate something to others because they can’t say it in words.4 | ||||

| • | Some may do it to get a “reaction” out of another person.3 | ||||

| • | Other kids say that they engage in NSSI in order to punish themselves because they feel they have done something bad or are bad kids.5 | ||||

What kinds of kids engage in NSSI?

| • | Any teenager can engage in NSSI—there really isn’t one type of person who might do it. | ||||

| • | However, it is important to know that many teens who engage in NSSI also have a psychiatric illness, like depression or anxiety, that may be causing the NSSI and is in need of professional attention and treatment. Once the depression or anxiety goes away, the urge to self-injure will likely go away as well.6 | ||||

When do kids engage in NSSI?

| • | Different feelings and situations can act as “cues” that elicit the urge to hurt oneself in a person who has been engaging in NSSI. | ||||

| • | Cues may include 1) a fight or argument with a boyfriend or girlfriend or parent, 2) strong negative feelings, like depression or anger, 3) pressure situations, like having to perform in front of others or taking a test. | ||||

Risks associated with NSSI: Why NSSI is dangerous for the mind and body

| • | First, engaging in NSSI is physically dangerous. For example, a child may hurt him/herself more severely than intended. Also, the instruments people use to hurt themselves can cause infection or disease (if not sanitary). Finally, the scars caused by NSSI are often permanent and can only be modified with plastic surgery. | ||||

| • | Second, engaging in NSSI can lead to long-term psychological distress. Although it may bring immediate relief, it usually leads to experiencing bad feelings, like shame, embarrassment, or disappointment, later. | ||||

| • | Third, engaging in NSSI often causes problems in one’s interpersonal relationships. People are often unsure how to react when they find out someone engages in NSSI, so they may avoid them or be judgmental of them. | ||||

| • | Overlap with suicide: Some kids who engage in NSSI also have thought about or tried to kill themselves. Engaging in NSSI may act to make people more likely to attempt suicide in the future.7 | ||||

How can interpersonal psychotherapy help?

| • | Interpersonal psychotherapy for self-injury can help teens learn to deal with their intense emotions by expressing them verbally rather than resorting to self-injury. | ||||

| • | In addition, IPT-ASI will help teens interact with their peers and family members in ways that reduce conflict and in turn will reduce the intensity of their negative emotions so they won’t want to self-injure. | ||||

| • | IPT-ASI will teach communication and problem-solving skills that allow teens to tell others how they feel rather than trying to show them through self-injury. | ||||

References

- 1. (1990). Suicide and the continuum of self-destructive behavior. Journal of American College Health, 38, 207–213. Google Scholar

- 2. (2002). Affect regulation and addictive aspects of repetitive self-injury in hospitalized adolescents. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 41, 1333–1341. Google Scholar

- 3. (2007). Characteristics and functions of non-suicidal self-injury in a community sample of adolescents. Psychological Medicine, 37, 1183–1192. Google Scholar

- 4. (2007). The functions of deliberate self-injury: A review of the evidence. Clinical Psychology Review, 27, 226–239. Google Scholar

- 5. (2002). Anorexia, masochism, self-mutilation, and autoerotism: The spider mother. Psychoanalytic Review, 89, 101–123. Google Scholar

- 6. (2008). Psychiatric impairment among adolescents engaging in different types of deliberate self-harm. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology, 37, 363–375. Google Scholar

- 7. (2007). Prevalence and psychological correlates of occasional and repetitive deliberate self-harm in adolescents. Archives of Pediatric and Adolescent Medicine, 161(7), 641–649. Google Scholar

Alternative Behaviors for Coping—ABCs

Below is a list of behaviors that are useful for helping people stop themselves from engaging in self-injury. The first set of behaviors, “replacement behaviors,” can be used in the short term to provide you with a physical sensation similar to that of self-injuring without the risks of self-injuring. However, we do not want you to use those types of behaviors for too long.

The second set of behaviors are behaviors that can help you distract yourself or sooth yourself when you are feeling negative feelings that make you want to self-injure.

Everyone is different. Therefore, ABCs that might work for one person may not work for someone else. Choose the behaviors that you think will work well for you.

“Replacement behaviors”—these behaviors can sometimes substitute an intense physical sensation in a safe way.

| • | Hold an ice cube in your hand and let it melt. | ||||

| • | Put your hand in a bowl of ice cold water. | ||||

| • | Place a rubber band or hair tie on your wrist and flick it (softly). | ||||

“Soothing and distracting behaviors”—these behaviors can help you to deal with strong negative emotions without self-injuring. Some of the behaviors will really help you to calm down; others will distract you for a while so that the urge to self-injure can pass. These behaviors can be used while we continue in treatment, aiming to decrease your negative emotions overall.

| • | Listen to your favorite song. | ||||

| • | Do yoga. | ||||

| • | Meditate. | ||||

| • | Light a scented candle. | ||||

| • | Apply scented lotion to your hands. | ||||

| • | Engage in slow, deep breathing. | ||||

| • | Go for a jog. | ||||

| • | Go for a walk. | ||||

| • | Call your best friend. | ||||

| • | Talk to your sister or brother. | ||||

| • | Talk to your mom. | ||||

| • | Go out with a friend. | ||||

| • | Write in your journal. | ||||

| • | Surf the internet | ||||

| • | Play a video game. | ||||

| • | Watch your favorite TV show. | ||||

| • | Watch your favorite movie. | ||||

| • | Read a novel. | ||||

| • | Paint or draw. | ||||

| • | Play with your dog or cat (or any other animal you have!). | ||||

What are some other behaviors that you think will work for you:

| 1. | _______________ | ||||

| 2. | _______________ | ||||

| 3. | _______________ | ||||

| 4. | _______________ | ||||

(2006). A Social-interactional model of the development of depressive symptoms in adolescence. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 74(1), 55–65.Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

(2007). Self-mutilation and coping strategies in a college sample. Suicide and Life Threatening Behavior, 37, 238–243.Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

(1985). The assessment of affective disorders in children and adolescents by semi-structured interview: test-retest reliability of the Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia for School-Age Children, Present Episode version. Archives of General Psychiatry, 42, 696–702.Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

(2005). Solving the puzzle of deliberate self-harm: The experiential avoidance model. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 44, 371–394.Crossref, Google Scholar

(2011). Dialectical behavioral therapy for adolescents (DBT-A): A clinical trial for patients with suicidal and self-injurious behavior and borderline symptoms with a one-year follow-up. Child and Adolescent Psychiatry and Mental Health, 5, 3. doi:10.1186/1753-2000-5-3Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

(2006). Risk factors for deliberate self-harm among female college students: The role and interaction of childhood maltreatment, emotional inexpressivity, and affect intensity/reactivity. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 76, 238–250.Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

(2010). Longitudinal Prediction of Adolescent Nonsuicidal Self-Injury: Examination of a Cognitive Vulnerability-Stress Model. Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology, 39(1), 77–89.Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

(2008). Psychiatric impairment among adolescents engaging in different types of deliberate self-harm. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology, 37, 363–375.Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

(1999). Testing the causal mediation component of Beck’s theory of depression: Evidence for specific mediation. Cognitive Therapy and Research, 23, 401–412.Crossref, Google Scholar

(2005). Adolescent sychiatric inpatients’ self-reported reasons for cutting themselves. The Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease, 192(12), 830–836.Crossref, Google Scholar

(2005). Nonsuicidal self-harm among community adolescents: Understanding the “whats” and “whys” of self-harm. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 34, 447–457.Crossref, Google Scholar

(1993). Cognitive-behavioral treatment for borderline personality disorder. New York: Guilford Press.Google Scholar

(1999). Perceived abuse and neglect as risk factors for suicidal behaviors in adolescent inpatients. The Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease, 187, 32–39.Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

(2007). Characteristics and functions of non-suicidal self-injury in a community sample of adolescents. Psychological Medicine, 37, 1183–1192.Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

(2010). A pilot evaluation of dialectical behavioural therapy in adolescent long-term inpatient care. Child and Adolescent Mental Health, 15, 193–196. doi:10.1111/j.1475-3588.2010.00569.Crossref, Google Scholar

(1999). Dialectical behavior therapy: A new treatment approach for suicidal adolescents. American Journal of Psychotherapy, 53, 413–417.Link, Google Scholar

(2004a). A randomized effectiveness trial of interpersonal psychotherapy for depressed adolescents. Archives of General Psychiatry, 61, 577–584.Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

(2004b). Interpersonal psychotherapy for depressed adolescents. (2nd Ed.) New York: The Guildford Press.Google Scholar

(2004c). A group adaptation of Interpersonal Psychotherapy for Depressed Adolescents. American Journal of Psychotherapy, 58, 220–238.Link, Google Scholar

(1999). Efficacy of interpersonal psychotherapy for depressed adolescents. Archives of General Psychiatry, 56, 573–579.Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

(2002). Affect regulation and addictive aspects of repetitive self-injury in hospitalized adolescents. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 41(11), 1333–1341.Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

(2007). The self-injurious thoughts and behaviors interview: development, reliability, and validity in an adolescent sample. Psychological Assessment, 19, 309–317.Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

(2006). Non-suicidal self-injury among adolescents: Diagnostic correlates and relation to suicide attempts. Psychiatry Research, 144, 65–72.Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

(2004). A Functional approach to the assessment of self-mutilative behavior. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 72(5), 885–890.Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

(1985). Children’s Depression Rating Scale-Revised. Psychopharmacology Bulletin, 21, 979–989.Google Scholar

(1990). Interpersonal loss and self-mutilation. Suicide and Life-Threatening Behavior, 20, 177–184.Medline, Google Scholar

(1999). The efficacy of cognitive-behavioral and interpersonal treatments for depression in Puerto Rican adolescents. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 67, 734–745.Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

(2000). Toward an interpersonal life-stress model of depression: The developmental context of stress generation. Development and Psychopathology, 12, 215–234.Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

(2010). Proposal to the DSM-V childhood disorder and mood disorder work groups to include non-suicidal self-injury (NSSI) as a DSM-V disorder. pp. 1–21. Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Association.Google Scholar

(2007).Brief dialectical behavior therapy (DBT-B) for suicidal behavior and non-suicidal self injury. Archives of Suicide Research, 11(4), 337–341. doi:10.1080/13811110701542069Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

(2006). Efficacy of Interpersonal Psychotherapy-Adolescents Skills Training: an indicated preventive intervention for depression. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 47, 1254–1262.Medline, Google Scholar