Psychodynamic Therapy for Depression in Women with Infants and Young Children

Abstract

Background: It has long been known that the rate of depression is high among women with infants and young children. In recent research a psychodynamic therapy group was found to be beneficial for a self-selected, postnatal subgroup of women who were of middle socio-economic status (SES), educated and who met DSM-IV criteria for clinical or subclinical depression. The current study sought to replicate these findings with individual psychodynamic therapy and to compare outcomes for three psychodynamic treatment conditions: individual, group, and combined individual and group.

Method: Patients began and left treatment from each of the three psychodynamic therapy conditions on a self-determined basis. Pre- and postintervention DSM-IV Global Assessment of Functioning (GAF) were obtained by reliable blind raters. A ten-variable, self-administered postintervention outcome questionnaire provided further data.

Results: Women (n = 58) in all three therapeutic conditions showed statistically significant improvement in their pre-to-post GAF and large treatment effects. On the questionnaire, they indicated that they were affected positively by all three conditions. Statistically significant differences among treatment conditions favored the individual treatment.

Conclusions: Psychodynamic therapy appears well suited for the population of women in this study, especially when administered on an individual basis. The model employed here emphasized receiving and developing empathic emotional attunement, insight into one’s relationships and early experiences, and a process for expressing feelings and resolving problems. Compared to group and combination therapies, the individual treatment may afford the greatest opportunity for receiving and developing these features and, thus, the best outcomes.

Introduction

Depressions following childbirth have been confusing to conceptualize and controversial to diagnose. They have sometimes been considered uniquely reproductively related disorders, making their initial appearance in the first year after childbirth (Hamilton, 1992). More often they are considered acute psychiatric postpartum disorders with comorbidity appearing in the first year after childbirth (Sichel & Driscoll, 2000) in women with a history of psychological disorders prior to childbirth. Both may be included in a subgroup often referred to as postpartum depression and which is frequently associated with a prevalence rate of 10–15% in childbearing women (Berry, 1998; Nonac & Cohen, 1998). Alternatively (or perhaps including), these subgroups of depression among women with infants and small children may be in a broad category of clinical and subclinical depressions ranging from mild to severe, like those seen at other times in women’s lives. Estimates of frequency rates for this larger postnatal depression group have been as high as 30% (Newsline, APA Monitor, 1997). The latter large group is the focus of this study. It is a group that may include women like those described in the writings of feminists such as Betty Freidan. In her book, The Feminine Mystique (1963), Freidan described role and identity struggles of educated women who were at home with young children. This group also includes cases with trauma histories like those upon which Freud (1895) based his early psychodynamic talking treatment. As conceptualized in this paper, postnatal depression is a phenomenon in mothers of infants and young children, resulting from a variety of potential causes, not only from the many changes that occur following childbirth.

Experimental Studies

Experimental psychological studies of treatment for postpartum and postnatal depression have appeared for only a few decades (Bledsoe & Grote, 2006). They are, for the most part, randomized control group, short-term studies of individual and group treatments.

Individual Therapy

Treatment effects have been obtained with several short term individual psychotherapies such as cognitive-behavior therapy (Cooper & Murray, 1997; Stowe et al., 1995), interpersonal therapy (O’Hara & Stuart, 2000), nondirective counseling and brief psychodynamic psychotherapy (Cooper & Murray, 1997; Cramer et al., 1990; Cramer & Stern, 1988). In comparison studies of short-term treatments, such as medication versus cognitive behavior therapy (Appleby et al., 1997) and psychodynamic versus cognitive-behavior versus nondirective counseling (Cooper & Murray, 1997), no consistent differences in treatment effectiveness have been found. Studies report that patients prefer psychotherapeutic treatments to medications postnatally as they raise fewer concerns among nursing mothers regarding side effects for the mothers and developmental issues for the infants. (e.g. Clark, 2003).

Therapy Groups

Group treatments are frequently recommended for postpartum depression because their inherent social support is often referenced as reducing the likelihood of depression (DeAngelis, 1997; Kruckman, 1992; Mueller, 1980; O’Hara, 1997). In keeping with this, research on group treatments has begun to appear. Among the earliest is an outcome study by Morris (1987) reporting improvement in relationships for a small group of women who received psychodynamic group therapy and home visits by cotherapists. More recently, the literature reveals a range of group treatments for which beneficial outcomes are reported, including CBT (Craig, Judd & Hodgins, 2005; Lane, Roufeil, Williams & Tweedie, 2001; Milgrom et al., 2005), support groups (Chen et al., 2000), counseling groups (Milgrom et al., 2005), interpersonal therapy groups (Klier, Muzik, Rosenblum & Lenz, 2001; Reay, Fisher, Robertson, Adams, & Owens, 2006) and eclectic group, which combined elements of mother-infant dyadic relational, CBT, interpersonal therapy and family systems (Clark, Keller, Fedderly, & Paulson, 1993; Clark, Tluczek, & Wenzel, 2003). All of these recent studies are based on short-term treatments and, with the exception of the two studies mentioned above (Chen et al., 2000; Milgrom et al., 2005), all are pilot studies with very small sample sizes. This author recently reported findings for an open trial supporting the benefits of an ongoing psychodynamic therapy group for depression in postnatal women (n=31). A large treatment-effect size was obtained pre- to post-intervention on the DSM Global Assessment of Functioning (GAF) for the women in the group intervention who also highly endorsed the psychodynamic therapy group on an outcome questionnaire (see Kurzweil, 2008a).

Combination Psychotherapies

PLAYSPACE is a combination prevention-treatment program. Its aim is to prevent psychopathology in infants and young children of women with postnatal depression. It does this by: (1) treating postnatal depression in mothers with group and individual “Relational-Developmental” (Kurzweil, 2008a, p. 17) psychodynamic psychotherapy (2) providing child care to facilitate individual parent therapy and (3) offering the children a stimulating play environment with peers and high-quality child care providers. It also provides a prolonged intervention. A preliminary open-trial outcome study (Kurzweil, 2008b) explored developmental variables in the children. It found indications of normative development in major developmental domains sampled, as well as a low rate of diagnosed psychological disorders. It found that the children’s global assessment of functioning (GAF) was significantly improved after the intervention and that they appeared to be functioning well at leave-taking. This research did not, however, study outcome of the mothers.

Goals of the Current Research

The current study explores and compares outcomes and effectiveness of three ongoing psychodynamic therapy conditions for women with a range of postnatal depression. They are:

| (1) | individual, | ||||

| (2) | group, and | ||||

| (3) | combination individual and group. | ||||

The goals were to replicate the effectiveness of psychodynamic therapy with individual and combination psychodynamic treatments for this population and to compare outcomes for the three psychodynamic conditions, thus contributing to guidelines for best practices for treating postnatal depression.

Methods

Participants and Procedures

Patients were self-referred after reading listings appearing in the local parents’ newspapers, insurance company directories, brochures placed in pediatrician and OB-GYN offices and directly from other health care professionals. Typically, interested clients were screened regarding their difficulties in an initial phone call. They were offered the three psychodynamic treatment options and an in-depth clinical interview was scheduled. Participation was facilitated for all three treatment conditions by offering child care on site, which featured an engaging play space with an experienced child care provider.

Data collection began in 1999 and ended in 2009. Letters were given to patients describing the general nature of the study and requesting their permission to participate by way of completing a questionnaire later in the treatment. Informed consent was received for the subjects with distribution of the letters and with their completed questionnaires. All women seen for 5 months or longer in the practice of one psychodynamic therapist, known for her postnatal specialty, were included. Blind rater evaluation data are available for n=58. Self-administered questionnaire data are available for n=38.

In general, these women are ages 25 to 50 years, of middle-class-economic status, educated and Caucasian, although there are many non-Caucasian women represented as well (See Table 1 for demographic profile). They are single as well as married. They are at-home and working outside home. Most participants had been in psychotherapy previously. For just over half, this was their first birth.

| Individual Condition n = 23 | Group Condition n = 20 | Combination Condition n = 15 | All Subjects n = 58 | |

| First Time Moms | 10 (43%) | 13 (65%) | 10 (70%) | 33 (57%) |

| Age of Youngest Child | Newborn–7 yrs | 5 wks–5 yrs | Newborn–3 yrs | Newborn–7 yrs |

| Child Under 2 Years | 16/23 70% | 18/20 90% | 12/15 80% | 46/58 80% |

| Middle SES | 23 (100%) | 20 (100%) | 15 (100%) | 58 (100%) |

| Caucasian/Af Amer, Latino, Asian | 16/7 (70/30%) | 19/1 (95–5%) | 15/0 (100–0%) | 50/8 (86/14%) |

| College Grad and/or Grad School | 23 (100%) | 17 (85%) | 15 (100%) | 55 (95%) |

| At-Home/Work & Home | 9/14 (39/61%) | 12/8 (60/40%) | 8/7 (51/47%) | 29/29 (50/50%) |

| Single | 6 (26%) | 4 (20%) | 3 (21%) | 13 (22%) |

| Previous Psychotherapy | 19 (83%) | 18 (90%) | 14 (93%) | 51 (88%) |

Table 1. PATIENT PROFILES: DEMOGRAPHIC VARIABLES

All participants had a DSM-IV diagnosis of Adjustment Disorder with Depression, Dysthymic Depression, or Major Depressive Disorder (American Psychiatric Association, 1994). Diagnoses were made by a licensed psychologist based on the initial clinical interview. Each condition contained a range of severity in diagnosis and this appeared comparable across the conditions. Most who were taking medications had begun their pharmaceutical regimen prior to beginning the study treatment. Mean duration in individual, group and combination treatments were 18 months, 14 months, and 21 months respectively. Overall, the range of stay was 5 months to 8 years. The group met for 1.5 hours every other week. Individual sessions were approximately 50 minutes. Thus, subjects in the individual condition received about 3.33 hours of treatment a month, Those in group received about 3 hours of treatment per month. Those in the combination received about 4.66 hours of treatment a month—3 hours of group and 1.66 of the individual. See Table 2 for the clinical profiles.

| Individual Condition n = 23 | Group Condition n = 20 | Combination Condition n = 15 | All Subject n = 58 | |

| Intensity of Study Treatment | ||||

| Sessions per month | 4–50 min | 2–90 min | 2–90 min + 2–50 min | |

| Means hours per month | 3 1/3 | 3 | 4 2/3 | Approx 3 2/3 |

| Medication | 6 (26%) | 4 (20%) | 5 (33%) | 15 (26%) |

| Only 3/58 initiated during study | ||||

| Duration of Study Therapy | (18) 7–46 | (14) 6–33 | (21) 5–108 | (17) 5–108 |

| (mean) months range | ||||

| DSM IV | ||||

| Adjustment | 6 (26%) | 5 (25%) | 3 (20%) | 14 (24%) |

| Disorder w | ||||

| Depression | ||||

| Dysthymic | 12 (52%) | 11 (55%) | 8 (53%) | 31 (53%) |

| Disorder | ||||

| Major Depressive Disorder | 5 (22%) | 4 (20%) | 4 (27%) | 13 (22%) |

| Disorder | ||||

Table 2. PATIENT PROFILES: CLINICAL VARIABLES

Most of the women had several risk factors for mental health problems, particularly divorce and affective disorders in the mother’s family of origin. Medical problems, loss in the patient’s family, and pregnancy/birthing complications were also frequently reported. See Table 3 for risk factor profiles.

| Individual Condition n = 23 | Group Condition n = 20 | Combination Condition n = 15 | All Subjects n = 55 | |

| Divorce | 6 (26%) | 9 (45%) | 7 (47%) | 22 (38%) |

| Sexual or Physical Abuse | 2 (9%) | 3 (15%) | 2 (13%) | 7 (12%) |

| Alcoholism in Parent | 1 (4%) | 5 (25%) | 5 (33%) | 11 (19%) |

| Affective Disorder in Parent | 14 (61%) | 7 (35%) | 8 (53%) | 29 (50%) |

| Medical Problem in Parent | 4 (17%) | 8 (40%) | 3 (20%) | 15 (26%) |

| Loss of Parent or Sibling | 1 (4%) | 6 (30%) | 5 (33%) | 12 (21%) |

| Recent Loss of Parent | 3 (13%) | 2 (10%) | 3 (20%) | 8 (14%) |

| Infertility History | 4 (17%) | 5 (25%) | 4 (27%) | 13 (22%) |

| Significant Medical Problem | 5 (22%) | 4 (20%) | 6 (40%) | 15 (26%) |

| Substance Abuse | 1 (4%) | 1 (5%) | 1 (7%) | 3 (5%) |

| History of Eating Disorder | 5 (22%) | 3 (15%) | 2 (13%) | 10 (17%) |

| Hospitalized for Mental Health | 2 (9%) | 3 (15%) | 0 (0%) | 5 (9%) |

| Pregnancy or Birth Complication | 8 (35%) | 7 (35%) | 4 (27%) | 19 (33%) |

| Child w/Medical Problem | 5 (22%) | 4 (20%) | 2 (13%) | 11 (19%) |

Table 3. PATIENT PROFILES: RISK FACTORS

Relational-Developmental Psychodynamic Therapy

A “Relational-Developmental” (Kurzweil, 2008a, p. 17) psychodynamic therapy approach was used in the three treatment conditions. The “Relational-Developmental” (Kurzweil, 2008a, p. 17) approach, as conceived by the author, has a fundamentally psychodynamically eclectic basis. Conceptually, it derives from research and literature on attachment and object relations (Bowlby, 1969, 1973, 1980; Winnicott, 1965, 1971), intersubjectivity (Stern, 1995, 2004) and self psychology (Kohut, 1971) and self development in women, (Miller, 1991), variations on Cultural-Relational theory and practice (e.g. Gilligan, 1982; Miller, 1986; Miller & Stiver, 1997) and developmental psychology (Emde, 2005, Fonagy, Gergely, Jurist & Target, 2002, Goleman, 1995; Piaget, 1952, Tronick, 1989; Vygotsky, 1978). Therapeutic action is explained with reference to Dynamic Systems Theory (e.g. Freeman 1999, Prigogine & Stenger, 1984; Thelen & Smith, 1994).

Briefly, the approach is relational in that it assumes what is most therapeutic is the relationship between the therapist and the patient. In this relationship the patient receives and develops the capacity for “empathic attunement” (Kurzweil, 2008a, p. 22) which is key to forming a trusting or therapeutic alliance. The therapy becomes a “holding environment” (Winnicott, 1965, p. 55) that is safe, supportive, stable, and validating; it is a place in which the individual and group members are comfortable, where emotional needs can be expressed, where the individual feels cared for, where patients can engage in a talking process to solve problems. As in Cultural-Relational theory and Relational Psychoanalysis, the presence of the therapist as an individual, apart from being a transference object or interpreter of emotional themes, is key. A Relational-Developmental view holds that the individual’s “working models” (Bowlby, 1973, p. 203) of relationship, and the expectations and interactions that these may lead to, are the primary sources of their emotional problems. There is the assumption that, through the therapeutic process, a new trusting attachment will be formed and that it will eventually replace the older internal “working model” (Bowlby, 1973, p. 203). Transference phenomena, and especially repetitive patterns, are relevant for analysis of relational themes and defenses, and these underlie interpretations and insight that contribute to therapeutic change.

It is further assumed that therapy is a developmental process, in which a new thoughtful mode to guide behavior replaces a less mature and dysfunctional one. This comes about through engaging in a process of deconstructing and insight, especially around childhood experiences, and eventually creating a coherent narrative, often from fragmented memories. In a sense, the therapist and group members act as scaffolding (as in Vygotsky’s developmental theory, 1978), enabling patients to form new constructs, akin to Piagetian (1952) schemata. The therapist uses an intersubjective talking process wherein emotions (e.g., anxiety, anger, frustration, depression) can be “dosed” (Emde, 2005, p. 123), regulated and transformed by the patient. Thus, the patient develops the capacity to engage in reflective process rather than respond impulsively, with anger, anxiety or depression and this results in functioning more effectively.

Growth occurs as described in theories of complex and dynamic systems (e.g. Freeman 1999, Prigogine & Stenger, 1984; Thelen & Smith, 1994). For example, these theories hold that after reaching a certain level of complexity, systems take on emergent properties and reorganize at higher levels of functioning. The process of change is not necessarily linear or predictable. Often a qualitative change occurs spontaneously, and there is a higher degree of coherence, specificity, and ability to differentiate. Thus, in building towards complexity of understanding as one does through reflective analytic process and intersubjective exploration, theory suggests that there is a natural tendency to reorganize on increasingly mature levels. Emotional growth does not require reinforcing approximations to a goal as in Cognitive-Behavioral Therapy.

As individual and group content are encouraged to range between the women’s past and present experiences, child rearing practices and emotional development are frequently discussed. In this regard, the Relational-Developmental approach is informed by the research and scholarly work of Developmental Behavioral Pediatrics (e.g. Brazelton, 1969, 1992; Greenspan, 1995; Greenspan and Greenspan, 1985; Tronick, 1989) and traditional child psychoanalytic theory (e.g. Anna Freud, 1965). This type of content is considered very important as these patients struggle with mothering issues and the parent-child relationship. Issues with parenting are thus directly worked on rather than framed as only unconscious or displaced unresolved issues from their lives. The latter may, of course, also be the case and if this is so it can eventually be discussed.

Measures

We asked patients to complete a questionnaire post treatment to rate the helpfulness of their therapy. The questionnaire was developed by the author because standard depression measures reviewed for adults were too limited in their focus on psychopathology and lacked attention to parenting variables. The measure devised was also made very easy to complete. Mothers were to rate, on a three point scale (positive, negative or not at all), how their treatments affected general wellbeing, parenting confidence, attunement with their child, frustration tolerance, mood, anxiety, sense of interpersonal connection, productivity, relationships, and outlook on life.

In addition, the Global Assessment of Functioning (GAF) from the DSM-IV was coded pre- and post - intervention. In all 58 cases the initial GAF was rated by the therapist (a clinically licensed psychologist) and was based on the initial intake interview. Outcome GAFs were rated by two coders, blind to the study, who had been trained on data previously coded by the therapist. Each coder scored about half of the cases. Scoring was done independently after reviewing case material with the therapist. Inter-rater reliabilities for the therapist and blind coders ranged from Pearson r=.86 to r=.99 on the data used for the final statistical analysis. Reliability checks were conducted after approximately 20%, 65%, and 100% of the data were scored. In all cases, ratings of the “blind” coders were used in the final statistical data analysis.

Results

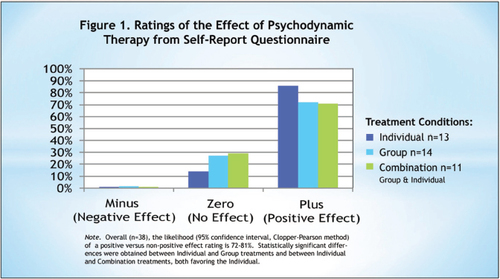

The majority of mothers for whom we had complete data (n=38) rated (on the Questionnaire) the psychodynamic therapy experience as positively affecting their sense of interpersonal connection and relationships (each 87%), general wellbeing (89%), outlook on life and parenting confidence (each 85%), mood (79%), and level of anxiety and frustration tolerance (each 67%). Not surprisingly, given our theoretical orientation, the relational variables (sense of interpersonal connection and relationships) and those thought to reflect on depression (general well being, mood and outlook on life) obtained the strongest endorsements, averaging positively improved for 87% and 85% respectively, of our sample. Variables reflecting on parenting (parenting confidence, attunement with your child) averaged positively affected for 79%. Productivity was by far the lowest, rated at 47% positively affected. On average, 76% of the women positively endorsed the items, suggesting they found the treatment to be very helpful. This compares well to the large-scale (4000 participants) readers’ survey of psychotherapy in Consumer Reports (1995, p. 735). That study concluded that “Therapy Works” based on 54% of participants who felt “very poor” at the outset, endorsing that “treatment made things a lot better.” In our study, all variables were positively endorsed by more than 65% of the women, except for productivity (47%). Positive-effect ratings were more than four times greater than no-effect ratings and negative rating was extremely rare. See Table 4 and Figure 1.

| Individual n = 13 | Group n = 14 | Combination n = 11 | All subjects n = 38 | |||||

| Positives | Positives | Positives | Positives | |||||

| Mean 86% | 95% CI | Mean 72% | 95% CI | Mean 71% | 95% CI | Mean 76% | 95% CI | |

| General Well-being | 92% | 66–99% | 93% | 69–99% | 82% | 50–97% | 89% | 76–96% |

| Parenting Confidence | 92% | 67–99% | 71% | 42–90% | 91% | 61–99% | 85% | 69–93% |

| Attunement with your Child | 85% | 57–97% | 71% | 42–90% | 64% | 33–86% | 73% | 58–87% |

| Frustration Tolerance | 85% | 57–97% | 43% | 21–69% | 73% | 39–92% | 67% | 49–80% |

| Mood | 92% | 67–99% | 71% | 42–90% | 73% | 39–92% | 79% | 64–90% |

| Anxiety | 92% | 67–99% | 64% | 37–85% | 45% | 20–75% | 67% | 51–82% |

| Sense of Connection | 77% | 48–93% | 93% | 69–99% | 91% | 61–99% | 87% | 73–95% |

| Productivity | 69% | 41–89% | 36% | 15–63% | 36% | 14–67% | 47% | 31–64% |

| Relationships | 92% | 67–99% | 93% | 69–99% | 73% | 39–92% | 87% | 73–95% |

| Outlook on Life | 85% | 57–97% | 86% | 58–97% | 82% | 50–97% | 85% | 69–93% |

Table 4. EFFECT OF PSYCHODYNAMIC THERAPY FROM SELF REPORT QUESTIONNAIRE Women were asked to rate their therapy as affecting them positively, no effect or negatively on the following variables:

A Kruskal-Wallis 3x3 analysis of variance was performed on the Questionnaire data. There were three ordered responses: Positive Effect (plus response), No effect (zero response) and Negative Effect (minus response). These were obtained for all ten questionnaire variables and compared among the individual, group, and combination conditions. The findings yielded: H= 10.18 (2 degrees of freedom), exact p-value=0.0059, indicating a significant difference on the questionnaire between the treatment conditions. Pairwise comparisons done with the Wilcoxon rank-sum test found that the individual versus group condition (exact p-value = .005) and the individual versus combination (exact p-value=.004) were significantly different both with higher ratings for the Individual, but the group versus combination condition was not statistically significant (exact p-value=.887). Thus, the individual condition resulted in better outcome ratings than the group or combination conditions based on self-report of the patients (See Figure 1).

FIGURE 1. RATINGS OF THE EFFECT OF PSYCHODYNAMIC THERAPY FROM SELF-REPORT QUESTIONNAIRE

Overall (n=58) all but one of the women showed improvement in the GAF rating from intake to final assessment. The mean GAF increased significantly, from 58.05 to 68.00, t=8.02, p<.000. This represents a large effect size: Cohen’s d=1.49.

For each condition significant improvement was found on the GAF. The individual condition mean increase was 11.60, t=10.17. p < .000. The group condition mean increase was 8.40, t=4.94, p<.001. The combination condition mean increase was 9.47, t=4.77, p<.001. Each represents a large effect size: Cohen’s d=2.17, 1.13, 1.28, respectively (See Table 5).

| Pre Therapy Mean | Post Therapy Mean | Mean Increase | SD | t | P< | Effect size Cohen’s d | |

| Individual n = 23 | 58.65 | 70.26 | 11.60 | 5.35 | 10.67 | .000 | 2.16 |

| Group n = 20 | 57.35 | 65.75 | 8.40 | 7.40 | 4.94 | .001 | 1.13 |

| Combination Individual/Group n = 15 | 58.06 | 67.53 | 9.47 | 7.42 | 4.77 | .001 | 1.27 |

| Overall n = 58 | 58.05 | 68.00 | 9.95 | 6.70 | 8.02 | .000 | 1.49 |

Table 5. CHANGES IN GAF PRE AND POST PSYCHODYNAMIC THERAPY

Comparison between treatment conditions (individual, group, combination) with the GAF measure was done with a regression model analysis of variance. This found a marginally significant F=3.0223 on 2 and 54 degrees of freedom, p = .057. However, the analysis of covariance found that the individual versus group comparison was significant: t=–2.42, p = .01, favoring the individual condition. This is consistent with the findings of the questionnaire.

The results also showed that patients in all three depression severity categories improved their GAF ratings. Because conditions do not differ with regard to SES and diagnosis (See Tables 1 and 2), the individual condition seems the best for the three diagnostic categories studied.

Discussion

Methodological Points and Future Directions

The subjects in this study self-selected therapist, type of therapy, psychodynamic treatment condition and length of treatment. In this sense, the study design represents the real world of psychotherapy practice. This would not be the case if subjects were randomly assigned to a therapist for a preset duration, type of therapy, and condition. Thus, the study contains good external validity. As with all open trials, internal validity may be compromised as we may not rule out spontaneous improvements. In this regard, we may consider the problematic nature of postnatal depression waiting list controls (e.g. Meager & Milgrom,1996) and what our clinical experience may lead us to believe about untreated depression. Regarding comparisons between the conditions favoring the individual, validity is bolstered by similarities for many variables in the patients’ profiles and risk factors across the three conditions including severity of depression. Treatment intensity and duration may be ruled out as bolstering the individual condition because these were greatest for the combination condition. There are, however, a small number of patients in the combination condition (n=15). Thus, replication of these finding is important. Likewise, a study with a larger number of patients in the Adjustment with Depression (n=13) and Major Depression categories (n=14) would be very beneficial in order to confirm that the individual psychodynamic treatment is the best for these diagnoses as well as dysthymia, which was the diagnosis of about half of the patients.

Medications may be ruled out as a confounding factor in this study as they were mostly begun by participants well before entering the study. Just a few cases (3/58) began medications during the study treatments. This is, however, an important area for future directions in the treatment of this population. While studies have compared drug versus therapy (e.g. Appleby et al., 1997), there are not studies of psychotherapy with and without medications for depression in women with infants and young children. It is probable that with the more severe cases, the medications play an essential role.

Finally, in terms of our conceptualization and formulation of the etiology of postnatal depression or depression in women with infants and young children, studies of the psychosocial profiles of women who present as healthy and well-adjusted in the postnatal period compared with the population of this study could be very illuminating about the hypothesis that depression in this population is rooted in the experiences of the women’s childhoods and present day relationships and conflicts.

Clinical Points

Patients in all three conditions indicated that they were positively affected by treatment, and their Global Assessment of Functioning, a widely used measure of general well being, showed significant improvement, suggesting that this population is a good match for the Relational-Developmental psychodynamic approach. The patients responded especially favorably to the individual treatment condition. Postnatal patients often like groups because these diminish isolation and can be less personal than a 1:1 therapy. However, these groups tend to be unstable in this population of women owing to the nature of life with infants and young children; this can be difficult for the women and the group leader. The individual condition does not have this built in stressor. It is highly stable and predictable.

As we think about why the Relational-Developmental psychodynamic approach is helpful to many women experiencing postnatal depression, their histories and their present day circumstances are striking.

Many of the women in our population have come to motherhood very needy themselves. There is much in the history of these women that suggests healthy intersubjectivity was not available to them growing up. They have not grown up with a talking process for understanding feelings and relationships. In many cases this seems to be due to parents with untreated depression, which was the case with nearly half of our subjects.

It also seems that there is much about which these women needed to talk. Many came with a history of trauma and/or abuse. One patient recalled how her alcoholic mother put her and her three older siblings out the lawn in the middle of the night so that they could go live with their father. The patient was 6 years old at the time. Another recalled enduring years of harsh, tyrannical, and demeaning treatment during musical training by the master music teacher. Another patient painfully recalled the sexual transgressions from an ill, alcoholic father and the humiliation she experienced when he exposed himself to people in the neighborhood.

There may be repressed memories with anxiety felt in the present, but without a sense of what happened earlier. One patient relayed becoming extremely anxious when her child turned 7 years old. It was the same age that she engaged in sexual transgressions with her 12-year-old brother. She recalled that as a child her anxiety was extremely strong during weekly church services. As is often the case, the patient did not discuss this experience with anyone as she was growing up. It’s very common for patients to recall traumatic childhood events as their children near the age at which the transgression occurred in the parent’s life. Realizing and understanding where the feelings are coming from can relieve a great deal of anxiety, and being able to process the experience with someone who is empathically attuned can bring resolution and closure.

In the absence of specific trauma to patients, there may be experiences of stress, chaos, or instability from earlier times, for example, years when a father was out of work and the attendant worried of becoming homeless and having to move and leave friends. Or, as in one patient’s case, when she and her siblings were sent to live with relatives for months after her father died and her mother had a car accident that required a lengthy hospital stay.

Add to these experiences and memories the difficulty of how to parent if one has not had “good enough parenting” (Winnicott, 1965, p. 5). One patient spoke of the special “spanking belt” conspicuously on display in her kitchen, a carryover from her immigrant mother’s third-world childhood. Many patients treated harshly as children for not behaving may find it extremely difficult to manage their children. They do not want to repeat the harsh treatment they received and they do not a have an enlightened repertoire upon which to draw for setting limits or helping children contain themselves. In many cases, if the patient is not helped to be a “good enough” parent, it will be difficult to make progress with the depression. Here, parental guidance might be a priority over a focus on personal themes.

Another factor to consider is that very often there are present-day, real-life stresses in the lives of these women. They may be dealing with an illness in the family or the recent loss of a parent. There may be demands to return to work sooner than desired, or they may have difficulty finding work that is badly needed for the family. There may be medical or temperamental factors in the infant, which are very stressful. There may be difficulties finding and affording suitable child care.

A final factor for this discussion is the present day support system of this population of women. Ideally, the mother will have what Stern calls “a supporting matrix” (Stern, 173, 1995) of other mothers, including one’s mother, mother-in-law, sisters, and sisters-in-law. These women help the new mother to reorient her psychic organization to the universal themes involved with ensuring the child’s well-being, growth, and attachment. They provide perspective through the rough spots. If this is lacking and the individual is isolated with few sources of support or reliable guidance to help solidify her identity as a mother and responsible adult, mental health can be greatly compromised.

In summary it is all or some combination of the following that have made the postnatal period very difficult or overwhelming for the population of women in this study:

| (1) | growing up without intersubjective process for transforming feelings | ||||

| (2) | experiences of trauma or abuse | ||||

| (3) | chaos due to stressful early life circumstances | ||||

| (4) | not being sure of how to be a “good enough parent” | ||||

| (5) | having current life circumstances that are very stressful | ||||

| (6) | being without stable and trustworthy relationships to provide support, guidance and validation in the years following childbirth. | ||||

In providing a “holding environment” (Winnicottt, 1965, p. 55) to sort out misleading internal “working models” (Bowlby, 1973, p. 203) the Relational-Developmental approach facilitates consolidating a new frame of reference and identity. It both provides the patient and helps her develop “empathic attunement” (Kurzweil, 22, 2008 a, b). It offers a model for gaining insight and problem solving. It models an intersubjective reflective process for transforming feelings, such as anxiety and depression, and developing resiliency.

Conclusion

In conclusion, Relational-Developmental psychodynamic therapy appears well suited for depression in educated, middle SES women with infants and young children. This is thought to be because Relational-Developmental psychodynamic therapy emphasizes receiving and developing the following features:

| (1) | empathic emotional attunement | ||||

| (2) | insight into one’s relationships and early experiences, and | ||||

| (3) | a talking process for expressing feelings and resolving problems. | ||||

Within comparable time frames for group and combination dynamic therapies, the individual therapy may offer the best opportunity for these relational-developmental features to evolve and, thus, the best outcome.

1.

2. (1997). A controlled study of fluoxetine and cognitive-behavioral counseling in the treatment of postnatal depression. British Medical Journal, 314, 932–6.Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

3. (1998).

4. (1969). Attachment and loss: Vol. 1. Attachment. New York: Basic Books.Google Scholar

5. (1973). Attachment and loss: Vol. 2. Separation. Anxiety and anger. New York: Basic Books.Google Scholar

6. (1980). Attachment and loss: Vol. 3. Loss. Sadness and depression. New York: Basic Books.Google Scholar

7. (1969). Infants and mothers: Differences in development. New York: Dell Publishing.Google Scholar

8. (1992). Touchpoints: Your child’s emotional and behavioral development. Reading, MA: Addison-Wesley Publishing.Google Scholar

9. (2000). Effects of support group intervention in postnatally distressed women: A controlled study in Taiwan. Journal of Psychosomatic Research, 49, 395–399.Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

10. (1993). Treating the relationship affected by postpartum depression: A group therapy model. Zero to Three, 13, 16–23.Google Scholar

11. (2003). Psychotherapy for postnatal depression: A preliminary report. American Journal of the Orthopsychiatry, 73, 441–454.Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

12. (1997).

13.

14. (1988). Evaluation of changes in mother-infant brief psychotherapy: A single case study. Infant Mental Health Journal, 9, 20–45.Crossref, Google Scholar

15. , (1990). Outcome evalulation of brief mother-infant psychotherapy: A preliminary report. Infant Mental Health Journal, 11, 278–300.Crossref, Google Scholar

16. (1997, Sept). There’s new hope for women with postpartum blues. APA Monitor, 28, 22.Google Scholar

17. (2005). A developmental orientation for contemporary psychoanalysis. In G GabbardE. PersonA. Cooper (Eds.), Textbook of Psychoanalysis (pp 117–130). Washington, D.C.: American Psychiatric Press.Google Scholar

18. (2002). Affect regulation, mentalization, and the development of self. New York: Other Press.Google Scholar

19. (1999) How brains make up their minds. London: Weidenfeld & Nicholson.Google Scholar

20. (1965) Normality and Pathology in Childhood, The writings of Anna Freud, Vol. 6. New York: International Universities Press.Google Scholar

21. (1982) In a Different Voice: Psychological theory and women’s development. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University PressGoogle Scholar

22. (1895) Studies in hysteria, Standard Edition, 2. London: Hogarth Press, 1955.Google Scholar

23. (1963). The feminine mystique. New York: Simon & Schuster.Google Scholar

24. (1982). In a different voice: Psychological theory and women’s development. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.Google Scholar

25. (1995). Emotional intelligence. New York: Bantam Books.Google Scholar

26. (1985). First Feelings: Milestones in the emotional development of your baby and child. New York: Viking.Google Scholar

27. (1995). The challenging child. Reading MA: Addison-Wesley.Google Scholar

28. (1993). A group therapy approach to postpartum depression. International Journal of Group Psychotherapy, 43, 191–203.Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

29. (1992).

30. (2011, Jan.). Hysteria or fragments of an obsessional neurosis. The Nora Theater Company, Central Square Theatre, Cambridge MAGoogle Scholar

31. (2001). Interpersonal psychotherapy adapted for the group setting in the treatment of postpartum depression. Journal of Psychotherapy Practice and Research, 10, 124–131.Medline, Google Scholar

32. (1971). Analysis of the self. In Monograph Series, Psychoanalytic Study of the Child. New Haven: Yale University Press.Google Scholar

33. (1992).

34. (2008). Relational-Developmental therapy group for postnatal depression. International Journal of Group Psychotherapy, 58(1), 17–34.Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

35. (2008). PLAYSPACE: A preventive intervention for infants and young children at risk from postnatal depression. International Journal of Mental Health Promotion,10 (1), 5–15.Crossref, Google Scholar

36. (2001). It’s just different in the country: Postnatal depression and group therapy in a rural setting. Social Work in Health Care, 34, 333–348.Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

37. (1996). Group treatment for postpartum depression: A pilot study. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry, 30, 852–860.Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

38. (2005). A randomized controlled trial of psychological intervention for postnatal depression. British Journal of Clinical Psychology, 44, 529–542.Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

39. (1986). Toward a new psychology of women. Boston: Beacon Press.Google Scholar

40. (1991). The development of women’s sense of self. In J. Jordan, , (Eds.), Women’s growth in connection (pp 11–34). Guilford Press: New York.Google Scholar

41. , (1997). The healing connection. Boston: Beacon Press.Google Scholar

42. (1987). Group psychotherapy for prolonged postnatal depression. British Journal of Medical Psychology, 60, 279–81.Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

43. (1980). Social networks: A promising direction for research on the relationship of the social environment to psychiatric disorder. Social Science Medicine, 14a, 147–161.Google Scholar

44.

45. (1998). Postpartum mood disorders: Diagnostic and treatment guidelines. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, 59, 34–40.Medline, Google Scholar

46. (1997). The nature of postpartum depressive disorders. In L. MurrayP. Cooper (Eds.), Postpartum depression and child development (pp. 3–35). New York: Guilford Press.Google Scholar

47. (2000). Efficacy of interpersonal psychotherapy for postpartum depression. Archives of General Psychiatry 57, 1039–1045.Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

48. (1952). Origins of intelligence in children. New York: International Universities Press.Crossref, Google Scholar

49. (1984). Order out of chaos: Man’s new dialogue with nature. New York: BantumGoogle Scholar

50. (2006). Group interpersonal psychotherapy for postnatal depression: A pilot study. Archives of Women’s Mental Health, 9, 31–39.Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

51. (2000). Women’s moods. New York: Harper Collins.Google Scholar

52. (1995). The motherhood constellation: A unified view of parent-infant psychotherapy. New York: Basic Books.Google Scholar

53. (2004). The present moment. New York: Norton & Company.Google Scholar

54. (1995). Sertraline in the treatment of women with postpartum depression. Depression, 3, 49–55.Crossref, Google Scholar

55. (1989). Emotion and emotional communication in infants..American Psychologist, 44, 112–119.Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

56. (1978). Mind in society: The development of higher psychological processes. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.Google Scholar

57. (1965).

58. (1971). Playing and reality. London: Routledge.Google Scholar