The Cardiac Rhythm of the Unconscious in a Case of Panic Disorder

Abstract

The field of psychodynamic psychotherapy would benefit from a comprehensive model that integrates its constructs with neurobiology. Research on the autonomic nervous system activity during the psychotherapeutic process is necessary because it is key in affective experiences and defensive behavior. The current case study reports physiological findings on heart rate dynamics in a patient suffering from panic disorder during two therapeutic sessions in which we used Davanloo’s Intensive Short-term Dynamic Psychotherapy. We looked at various metrics of heart rate variability during the therapeutic process leading to breakthrough of unconscious feelings. The measurements included sympathetic and parasympathetic indices, vagal tone, and their responses. Our results suggest that the sympathetic system activates during defensive responses associated with anxiety and during the passage of unconscious-aggressive impulses. Following the experience of unconscious guilt, there is an increased vagal tone corresponding to the phase of reunification with the attachment figure. Findings are discussed integrating developmental neurobiology and clinical psychodynamics.

Introduction

Psychodynamic psychotherapy is interested in understanding the mechanisms leading to symptom formation and character disturbances through in-depth investigation of childhood events and quality of past relationships. The main therapeutic task is uncovering repressed events and feelings to understand the origins of symptoms. Cognitive insight has been the main curative factor in psychoanalytic psychotherapy, but we now recognize the importance of emotional experience in the process of psychological change. Damasio’s (1996) somatic marker hypothesis illustrated how embodied emotions can influence higher-level decision-making and cognitive processes. However, despite Freud’s 1914 prediction that biology would be able to explain psychodynamic processes (Freud, 1957), we still fall short of a comprehensive model integrating neurobiology and psychotherapy.

Several studies have used brain imaging techniques to demonstrate changes in brain activation following successful psychotherapeutic intervention (Barsaglini, Sartori, Benetti, Pettersson-Yeo, & Mechelli, 2013). While this approach shows that psychotherapy provokes measurable neurobiological effects, it does not allow a better understanding of the active therapeutic process. Alternatively, psychophysiological research demonstrates that autonomic responses carry information that distinguishes specific emotions (Ekman, 1992; Kragel & Labar, 2013) and supports the autonomic nervous system (ANS) in mediating human behaviour in fear and aggression, i.e. the fight or flight response. Anger, for example, is associated with a relative dominance of sympathetic activation (Marci, Glick, Loh, & Dougherty, 2007; McCraty, Atkinson, Tiller, Rein, & Watkins, 1995).

Measurement of the ANS has an advantage over brain imaging techniques since it can be done in real-time during a psychotherapy session and allows moment-to-moment measurement of the affective response in an objective way. Heart rate variability (HRV), a measure of beat-to-beat variation, or R-R interval on an electrocardiogram (ECG), are non-invasive indices of the cardiac sympathovagal balance. It reflects the balance between each component of the ANS, the sympathetic nervous system (SNS) and the parasympathetic nervous system (PNS) and their input on the heart rhythm. Heart rate variability is reduced in depression (Carney et al., 2005; Musselman, Evans, & Nemeroff, 1998), generalized anxiety disorder (Thayer, Friedman, & Borkovec, 1996), panic disorder (Cohen et al., 2000; Klein, Cnaani, Harel, Braun, & Ben-Haim, 1995) and post-traumatic stress disorder (Cohen et al., 2000). Thayer and Lane (Thayer & Lane, 2000) proposed a neurovisceral model of self-regulation where HRV represents an index of effective feedback between the central nervous system (CNS) and the ANS, which reflects the adaptation capacity of an individual facing his environment. Others proposed that self-regulation, the capacity of an individual to regulate attentional and affective states, is reflected by the ANS regulation (Porges, 2003a) and depends on gene-environment interactions through development (Schore, 1997, 2000). Schore (2009) suggested that disruption of attachment bond through development leads to a regulatory failure and an impaired autonomic homeostasis.

The polyvagal theory (Porges, 1995) uses a phylogenetic model to explain the role of the ANS and other brain structures in regulating social interactions and defensive behaviours. The most phylogenetically primitive component of the ANS would be the immobilization system (e.g. feigning death, behavioural shutdown), followed by the mobilization system (fight or flight), which depends on sympathetic activity. Through evolution, the mammalian nervous system developed a new neural strategy to inhibit primitive defensive responses of fight or flight and allow social bonding and interactions in a safe environment. A new vagal brake emerged through development of myelinated fibers of the vagus and allowed the emergence of the social engagement system (SES), by calming the individual and inhibiting the sympathetic influence on the heart rate (Porges, 2003b). The SES would represent the third and final stage in the development of the mammalian ANS. According to Porges theory, this vagal brake is necessary for effective self-regulation of the individual, which allows maintaining a calm state in social contexts, while its rapid withdrawal promotes defensive mobilization strategies. Porges (1995) proposed that this vagal brake could be indexed through measurement of the amplitude of the respiratory sinus arrhythmia (RSA), a natural rhythm in the heart rate pattern at approximately the frequency of spontaneous breathing.

The respiratory sinus arrhythmia, therefore, represents a potential biomarker of flexibility in the regulation of social and defensive behaviours. A study found that the RSA response to presentation of various emotional videos differs in individuals diagnosed with borderline personality disorder from controls (Austin, Riniolo, & Porges, 2007). Patients with borderline personality disorder demonstrated a physiological state supporting mobilization behaviour, while controls were in a physiological state supporting social engagement behaviour. Porges also introduced the term neuroception to describe the unconscious process that detects whether a situation is safe, dangerous or life-threatening (Porges, 2003b). This function depends on subcortical neural circuits in the brain (e.g. limbic), but became regulated with cortical structures in mammals through evolution improving adaptation. Activation of the SES with inhibition of the defensive system constitutes an appropriate response in a safe environment, whereas the persistence of the defensive system leads to psychopathology such as anxiety disorders or borderline personality (Austin et al., 2007). Lower vagal tone has also been found in defensive subjects, who tend to deny common weaknesses and endorse uncommon virtues when compared to less defensive subjects (Movius & Allen, 2005). In summary, the polyvagal theory offers an interesting neurobiological paradigm for psychotherapy looking at the evolution of the ANS and its role the unconscious regulation of risk assessment and defensive strategies.

We need to concentrate our efforts on therapeutic models that bring affective responses in patients, and we can do this by searching for integration of psychodynamics with biology and understanding of the physiology of the unconscious. Davanloo’s technique of Intensive Short-Term Dynamic Psychotherapy (IS-TDP) (Davanloo, 1990, 2000, 2005) offers advantages beyond more classical psychodynamic approach to study the physiological response of the ANS during a therapeutic session. In part, this is because of predictable sequence of affective arousal during sessions. A review of 89 cases treated with a therapeutic modality described as IS-TDP demonstrated that access to a higher intensity of affect-laden content in therapy was associated with better outcome (Town, Abbass, & Bernier, 2013). Davanloo developed a specific technique that removes resistance rapidly, allowing the patient to move from his rigid defensive stance to a state of experiencing true feelings which have been buried deep into the unconscious. Recent data from a small meta-analysis suggest that IS-TDP could be effective for a broad range of conditions such as anxiety, depression, personality disorders and somatization disorders (Abbass, Town, & Driessen, 2012).

Davanloo’s technique of IS-TDP and Metapsychology

Davanloo’s clinical approach offers specific technical interventions to handle resistance and rapidly brings the patient to experience the affective unconscious, often in the first session. Rather than using interpretation, the therapist concentrates on mobilizing the transference feelings which leads to a tilting of the unconscious resistance in the transference, or transference component of the resistance (TCR).

Once the resistance is crystallized in the transference, the therapist uses an intervention called “head-on collision (HOC) with the resistance” (Davanloo, 1999), which contains important communication to the patient’s healthy self. The HOC constitutes an invitation to the patient to give up self-destructive aspects associated with the resistance, and to share his deepest feelings openly with the therapist. According to Davanloo, a breakthrough in the affective zone of the unconscious will be proportional to the intensity of the TCR mobilized, i.e. the intensity of the transference feelings. From the patient’s perspective, a breakthrough in the unconscious consists of the experience of strong emotions, such as rage, guilt, and deep affection to attachment figures.

The infant first metapsychologically establishes a strong bond and attachment to the parental figure, which can be traumatized to various degrees during the first few years of life. Davanloo proposes that in reaction to the trauma, that the infant experiences a deep pain and primitive rage towards the attachment figure. The experience of this primitive rage mobilizes a feeling of intense guilt in the child, because of the existing bond and love for the attachment figure. This intense guilt feeling is so painful that it needs to be repressed in the unconscious, leading to symptom formation and character pathology. In Davanloo’s metapsychology, the trauma leads to a fusion between the primitive rage and the guilt in the unconscious, which becomes the nucleus of the neurotic structure and manifests itself by resistance. Without proper therapeutic intervention, guilt, and primitive rage remain fused in the unconscious, demanding suffering and self-destructiveness, sometimes referred to as the “perpetrator of the unconscious” (Beeber, 1999a, 1999b, 1999c). Davanloo conceptualizes resistance as the presence of primitive rage and guilt in a fused state, locked in the unconscious, a driving force in the neurotic search for suffering.

Davanloo’s IS-TDP aims at eliminating the resistance by helping the patient experiences unresolved feelings towards attachment figures in the transference with the therapist. The technique allows a rapid and direct access to the emotional repressed unconscious, in partnership with the therapist and subsequent intellectual insight. Breaking through the affective unconscious with Davanloo’s method follows a process called the central dynamic sequence (CDS).

The Central Dynamic Sequence (CDS) in Davanloo’s IS-TDP (Davanloo, 2005)

| 1. | The phase of pressure and tilting: pressure to experience of transference feelings and blockade of tactical defenses create tension in the therapeutic process | ||||

| 2. | Mobilization of the transference component of the resistance (TCR): character resistance becomes directed more specifically at the therapist | ||||

| 3. | Mobilization of the aggressive impulse or murderous rage (MR) in the transference: the patient experiences the “neurobiological pathway” of primitive rage often described as a sensation of power, energy or heat that starts in the pelvis, spreads into the abdomen, chest, shoulders, arms and towards the hands (Davanloo, 2000) | ||||

| 4. | Mobilization of the unconscious therapeutic alliance (UTA): the visual imagery of the therapist becomes replaced by the imagery of an attachment figure | ||||

| 5. | Passage and experience of unconscious guilt: the patient experiences painful guilt feelings for having aggressive impulse towards the attachment figure. After moving beyond feelings of rage and guilt, the patient feels the love and closeness to the attachment figure. | ||||

| 6. | Phase of forgiveness : the patient expresses his wish to forgive the attachment figure for previous empathic failure in the relationship. | ||||

| 7. | Phase of consolidation with psychic integration and unconscious structural changes: the patient and the therapist review together the therapeutic process including analysis of the defenses, resistance and transference. Further dynamic exploration of the patient’s developmental history also takes place for therapeutic planning. | ||||

The goal of this case study was to determine a patient’s affective response through measurement of HRV and RSA during Davanloo’s IS-TDP. More specifically, we wanted to assess the variations of the ANS activity in a subject passing from a state of unconscious resistance to breakthrough to the experience of repressed feelings of rage and guilt. We hypothesized that specific feelings (anxiety, rage, guilt) would be associated with distinct pattern of ANS activity (sympathetic and parasympathetic activity). We also hypothesized that RSA would increase following a breakthrough into the unconscious with the experience of closeness with the attachment figure.

Methodology

The research protocol was approved by the ethics board of the Montfort Hospital in Ottawa, Ontario, Canada. After signing the informed consent form, the patient was assessed by an independent psychiatrist (I.B.C.) using the Mini International Neuropsychiatric Interview (MINI, (Sheehan et al., 1998)) to provide a clinical diagnosis based on the DSM-IV classification. Potential subjects for this study had to meet DSM-IV criteria for an anxiety, a depressive disorder or a cluster C personality disorder and be interested in short-term dynamic psychotherapy. Subjects who were acutely suicidal or meeting criteria for an acute clinical depression, bipolar disorder, substance dependence or previous psychotic episodes were excluded. Potential subjects taking medication that could affect heart rhythm (e.g. beta-blocker) were also excluded. Once inclusion criteria were verified, psychotherapeutic interviews with another clinician (G.F.) were scheduled. Prior to each psychotherapeutic session, the subject filled the Outcome Questionnaire OQ-45 (M. J. B. Lambert, G.M., 1996) to estimate symptom severity and treatment response.

During each psychotherapeutic session, the patient’s heart rate was monitored using a Polar watch RS800CX (Polar Electro Oy, Kempele, Finland) with its thoracic band. Beat-to-beat cardiac intervals (R-R intervals) were recorded using the Polar watch with a resolution of 1 millisecond. After recording, data were uploaded to a PC using the manufacturer-supplied software (Polar ProTrainer 5.0). The R-R intervals from selected psychotherapeutic segments were exported in ASCII format and processed through CMetX Cardiac Metric Software (Allen, Chambers, & Towers, 2007). The CMetX provide the usual measures of HRV including the cardiac vagal index (CVI), the cardiac sympathetic index (CSI) (Toichi, Sugiura, Murai, & Sengoku, 1997) and the respiratory sinus arrhythmia (RSA) derived from Porges method (Porges, 1995). One-minute duration of consecutive segments of R-R intervals provided measures of CVI and CSI during the whole course of the psychotherapy session. Four-minute duration of consecutive segments of R-R intervals were used to determine variations of RSA during each session.

Each psychotherapeutic session consisted in the application of the CDS as described by Davanloo (Davanloo, 2005). Psychotherapeutic sessions usually take place on a weekly basis and each session lasts between 50 to 90 minutes.

Case presentation

The patient is a 22-year-old female, university student, single, and with no child. The patient presented herself to the hospital emergency room during fall of 2012 for anxiety symptoms. She voluntarily was admitted for three days for a crisis intervention. She reported that since the university term began, she had experienced more anxiety than usual, with performance anxiety, a tendency to ruminate, insomnia and abdominal pain, which she attributed to nervousness. She also reported nausea and poor appetite of several weeks duration. She felt overwhelmed by the workload of school, had become dependent in relationship to her roommate, and started to contemplate suicide as an escape.

The patient had a history of struggling with anxiety symptoms on an intermittent basis since the age of eight years old, and saw a psychologist using a cognitive-behavioral therapy model for about one year in 2009 with the focus on her anxiety symptoms. She never attempted suicide, and was never admitted to the hospital prior to 2012. Before the patient’s current admission to the hospital, her family physician started her on clonazepam (1 mg once daily) and escitalopram (10 mg once daily), a medication she was on for two years from age 19 to 21.

She had an older brother who also suffered from anxiety. Her mother was a successful professional who died of cancer when the patient was 11 years old. The patient initially reported she was very close to her mother, who was a gentle and affectionate maternal figure. She described her father as a demanding perfectionist, who struggled significantly after his wife passed away, and required his daughter’s caregiving over several months.

The patient described herself as easily overwhelmed and lacking self-confidence, which lead to dependency in relationships. As a teenager, she often clashed with her father, who felt she was being manipulative, and she created anxiety symptoms to get attention. The patient and her father frequently had arguments about her lack of autonomy.

The patient received psychotherapeutic intervention during her brief admission to the hospital before she participated in this research project. She remained on escitalopram 10 mg o.d. During her inpatient stay, the patient had three sessions of Davanloo’s IS-TDP, which revealed a defensive structure with regressive elements, such as becoming tearfully distraught in situations of conflict, feeling helpless, and adopting a dependent position toward others. She also demonstrated obsessional character defenses, such as rumination, rationalization, and intellectualization. Therefore, before participating in this research protocol, she already had psychotherapeutic sessions with breakthroughs of rage and guilt in relationship to her father, and she also experienced grief feelings in relationship to her mother. The patient was not naive to the therapeutic process which was still however in an early phase.

Results

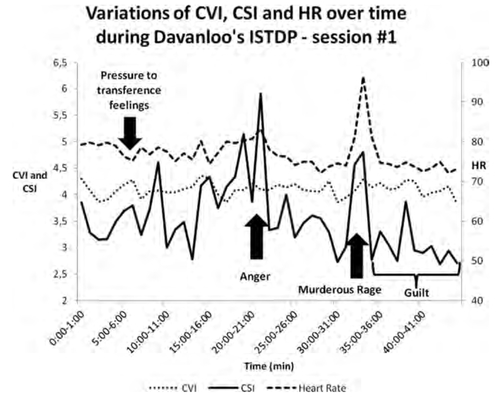

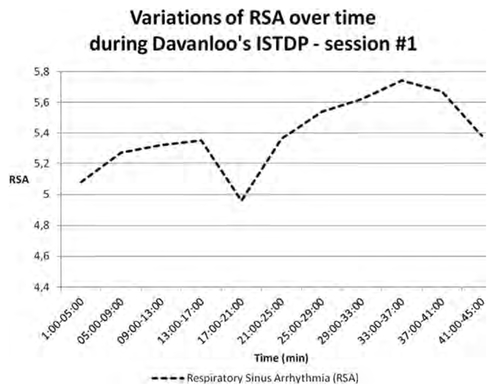

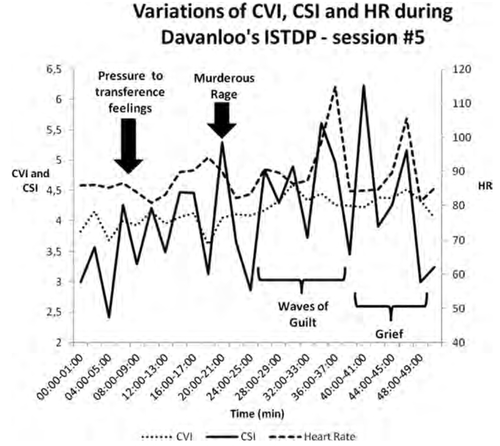

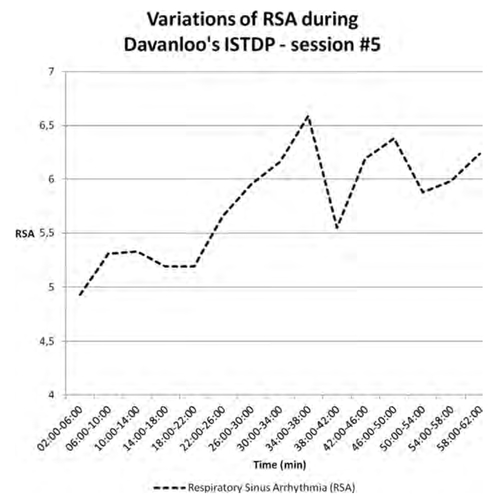

The MINI (Mini-International Neuropsychiatric Interview] provided a DSM-IV diagnosis of Panic disorder. Heart rate variability was obtained during five consecutive psychotherapeutic sessions with the subject. We selected data for sessions #1 and #5 for the present report because of the quality of the recording (i.e. relative absence of artifacts). Variations of Heart Rate (HR), CSI, CVI and RSA during each psychotherapy session were plotted on four graphs using Microsoft Excel. Figure 1 shows variations of HR, CVI, and CSI for the first session. The phase of pressure to transference feelings is associated with a relative increased in sympathetic activity as estimated by CSI, as well as some increased in vagal activity indicated by CVI. During this phase, the subject experienced anxiety and used various defense mechanisms. During the experience of anger and murderous rage, there was a marked increased in CSI. The passage of murderous rage was preceded, however, by a relative drop in CSI. There was some increased in CSI during the passage of guilt feelings. Cardiac vagal index remained relatively stable during the session. Figure 2 represents variations of RSA during session #1. RSA appears to increase during the session. However, RSA decreased during the 4-minute segment containing the experience of anger mixed with anxiety. Figure 3 shows variations of HR, CVI, and CSI during session #5. The phase of pressure to transference feelings accompanied by anxiety in the subject is associated with increased in CSI. There was an increased in CSI during the passage of murderous rage, once again preceded with a relative drop in CSI.

Figure 1. HR: HEART RATE

CVI: CARDIAC VAGAL INDEX

CS: CARDIAC SYMPATHETIC INDEX

Passages of guilt and grief were associated with intermittent increases in CSI. Figure 4 illustrates the variations of RSA during session #5. Respiratory sinus arrhythmia increased during the overall course of the session and peaked during the passage of guilt.

A summary of session #1 is provided to describe the psychotherapeutic process with corresponding time under parenthesis. For session #5, verbatim of specific segments with their corresponding time under parenthesis were selected to illustrate each phase of the CDS.

Summary of session #1:

The process started with inquiry into the patient’s symptomatology. She elaborated on her anxiety regarding performance in school and her current fear that she would become so dysfunctional she would need hospitalization. As the therapist offered a summary of their previous work, emphasizing the therapeutic task and pointing out the patient’s selfdestructive tendencies. The patient used the defense of “weepiness,” which indicated some mobilization of transference feelings (7:00). We followed this, by pressuring the patient to experience transference feelings and by explaining how she used defenses to avoid feelings. As the therapist applied pressure to the transference feelings, the patient started to sigh and show muscle tension indicating discharge of anxiety at the level of the striated muscles (8:35).

Figure 3. HR: HEART RATE

CVI: CARDIAC VAGAL INDEX

CS: CARDIAC SYMPATHETIC INDEX

Later, the patient declared that she was angry at the therapist (17:00), and described physical manifestations of anxiety (tension in the abdomen, constriction of the vocal chords). Because the therapist recognized regressive defenses in the patient, he left the transference for a moment and asked the patient about the last time she had a conflict with someone. This graded approach increased the patient’s capacity to experience her anger without using regressive defenses (Davanloo, 1990). She described a recent incident with her roommate. She explained she felt dismissed, which mobilized anger (20:00). The therapist again put pressure on the physical experience of anger, which the patient resisted with various defensive strategies (for example, helplessness: “I am not able to experience my anger”), and the patient continued to experience anxiety instead of anger. Davanloo described that individuals with character neuroses are unable to differentiate between anxiety and anger resulting from resistance (Davanloo, 2005).

The patient’s character resistance was clarified and blocked, leading to an overall tilting of the resistance in the transference. The therapist then used the technique of HOC (28:00), followed by pressure to experience transference feelings. The patient finally experienced the neurobiological pathway of murderous rage (32:00), describing “it is power, and it is pushing up through my chest and my hands.” The therapist then asked the patient to fantasize how she would unleash that rage on the therapist. The patient described how she would push him against the wall, stomp on his stomach, twist his arms and choke him. Looking at the dead body of the therapist on the floor, the patient identified features of her father—“it is my Dad” (39:25), which led to the mobilization and experience of the unconscious guilt with waves of sobbing. After several minutes of sobbing in pain, the patient described how she has had visual imagery of her father at his funeral (48:00). She described how she would say her final goodbye to him (“I love you”), and he would respond (“I forgive you”). With tremendous pain, she also remembered that during the year following her mother’s death, she told a friend that she would have preferred her father died instead.

The session ended by reviewing the process and investigating past relationships with her father, mother, and brother. Since the patient had a tendency to experience abdominal pain when anxious, the therapist did an analysis of the mechanism of symptom formation with projective identification to the attacked father (“I would stomp on your stomach”). Psychic integration regarding the triangle of conflict was also done by reviewing the difference in the experience of anxiety, defense, and impulse.

Brief summary of sessions #2, #3 and #4

During session #2, the patient reported an incident where she experienced rejection associated with anxiety symptoms during a recent social situation. Behind the subjective feeling of anxiety, she was able to identify that she was angry, indicating that some psychic integration had taken placed since the previous session. The process led to a breakthrough of murderous rage in the transference, with passage of guilt feelings as the visual imagery of the therapist became her brother. In session #3, the patient experienced painful feelings of grief about her mother. This was related to long hours she spent away from home at work. During session #4, the patient had a breakthrough of murderous rage in the transference, with experience of guilt towards her father. The patient expressed how she was regretful about having demonized her relationship with her father since the death of her mother. She also reported a positive memory: when she was young, her father used to put her to sleep with tenderness.

Physiological response to the CDS during session #5:

| 1. | The phase of pressure and tilting in the transference (Minutes 0:00 [the beginning of the session] to 4:30) Patient: “I had a pretty good week. I felt a lot better after our previous session than I have before the session. I feel relaxed.” Therapist: “What was the experience after the session?” Patient: “Tired but a lot more relaxed. There was less of a burden.” Therapist: “How about anxiety, did you feel any after the last session?” Patient: “Barely any.” Therapist: “Are you still taking clonazepam?” Patient: “I did not take any since our session.” Therapist: “So, despite the fact you discontinued clonazepam, you notice that you do not experience anxiety. Why did you decide to stop clonazepam?” Patient: “Because the clonazepam is there only when things are really bad.” Therapist: “Do you think our session was helpful to reduce the anxiety?” Patient: “Yeah. It was to a point that I have never bounced back so quickly from an anxiety attack.” Therapist: “We need to be honest and look into this objectively. Last week, you experienced a load of murderous rage towards your father followed by the experience of massive guilt. Then, the anxiety collapsed, to the point that you did not need your clonazepam anymore, which is your favorite crutch. Now, are you saying to me that you are ready to give up the crutch and become a free woman?” Patient: “Yes.” Therapist: “Because this is our task, if you want to do it, or you can go back to your destructiveness. One session is not enough to complete the task. There is a massive load in you that we need to evacuate if you want. You know you have the capacity, but the need in you to punish yourself and be destructive is very high. Could we see now how you feel towards me because I notice you are avoiding my eyes?” Patient: (the patient takes a sigh) “I am anxious.” Therapist: “Could we see how do you feel behind this anxiety, how do you feel towards me?” (4:30 minutes) The patient communicates to the therapist that she is feeling anxious, which indicates that there is mobilization of transference feelings. At this point, the task of the therapist is to continue to apply pressure to the experience of the transference feelings which will lead to the crystallization of the character resistance in the transference. | ||||

| 2. | Mobilization of the transference component of the resistance (TCR) (Minutes 7:00 to 12:30) With further pressure to transference feelings, the patient’s resistance manifest itself in the form of avoidance, denial of feelings (“I feel nothing”) and finally resorting to take an incapable position in relationship to her feelings. The therapist applied a short form of head-on collision with the resistance which helped the patient starting to experience her feelings in the transference. Therapist: “There are feelings in your eyes if you are honest with me. If you do not erect a wall here with me, let’s see how do you feel towards me? We know you have a great potential and that you are a capable woman, but there is still a wall here with me, and it is a destructive wall. But you are also free to be destructive and to portray yourself as incapable. Let’s see if you can give up this destructive position, let’s see how do you feel with me?” Patient: “I feel angry”. At this point, the patient experiences anger in the transference mixed with anxiety. The task of the therapist is to help the patient connect with the internal rage and experience it physically without any anxiety. Anxiety manifests itself in this patient with the use of regressive defense such as describing herself as “incapable” of experiencing her feelings. | ||||

| 3. | Mobilization of murderous rage (MR) in the transference (19:45 to 22:45) Therapist: “If you do not take a paralyzed position with your feelings, how do you experience the viciousness right now? It is in your eyes. How do you experience the viciousness without the crippling anxiety?” Patient: “There is power in my chest.” Therapist: “If you were to unleash physically on me, how would you go at me physically, in thoughts and fantasy?” Patient: “I would push you against the wall, I would keep hitting you.” Therapist: “Face with the full intensity, what else would you do?” Patient: “I would hit you in the face, step on your stomach … grab your arm and pull it. I would keep my leg on your throat to prevent you from breathing … until you stop breathing.” | ||||

| 4. | Mobilization of the unconscious therapeutic alliance (UTA (Minutes 23:00 to 24:00) The therapist asked the patient to describe the imagery associated with the dead body of the therapist. The patient reports that instead of seeing the therapist, she sees the blue eyes of her mother. | ||||

| 5. | Passage and experience of unconscious guilt (Minutes 25:30 to 38:00) With the dead body of the therapist replaced by the murdered body of the mother, the patient experiences intense waves of painful guilt. Patient: “There is blood and bruises everywhere” (sobbing) Therapist: “Face with your feelings, you love your mother very much.” | ||||

| 6. | Phase of forgiveness (Minutes 31:00 to 35:00) Therapist: “If you could talk to her before her last breath, what would you say to her?” Patient: “I’m sorry, I love you. I would give her a hug and hold her.” | ||||

| 7. | Phase of consolidation with psychic integration and unconscious structural change (Minutes 38:00 to 49:00) | ||||

The patient and therapist explored the patient’s relationship with her mother. The patient explained how she resented her mother for having a long illness that prevented the patient from having a “normal childhood.” The patient explained she resented her mother’s long illness and how it deprived the patient of a “normal childhood.” She also described how guilty she felt about having financial benefits from the life insurance policy since the loss of her mother. A shift began in the patient’s intrapsychic system from an idealized mother to a better-integrated representation.

Results of the OQ-45

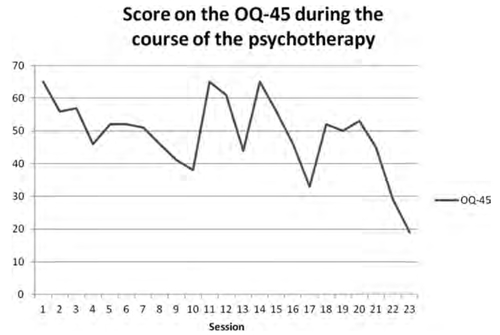

Figure #5 presents the score of the OQ-45 during the full course of psychotherapy. The patient’s total score on the OQ-45 at entry in the research protocol was 65 (a score of 63 or more indicates overall psychological symptoms of clinical significance [M. J. Lambert et al., 1996]). A week after the fifth session the patient’s scored 51 on the OQ-45. Scores on the OQ-45 support a positive response to the five psychotherapy sessions during the research study, representing the early phase of the overall treatment. Following the first five sessions, each subscale score on the OQ-45 showed improvement from baseline. The SD subscale (Symptom Distress) dropped from 38 to 30, the IR subscale (Interpersonal Relations) from 12 to 7, and SR subscale (Social Role) from 15 to 14. For the first 10 sessions of treatment, we notice a strong tendency for symptomatic improvement as measured against the OQ-45 total scores. This phase of treatment focused mostly on murderous rage and guilt towards the patient’s father. From session #10 to #22, the focus of the treatment moved to breaking through the murderous rage and guilt towards the patient’s mother. That part of the treatment was associated with more variation on the OQ-45 total scores, with a stable decrease at the end. At the end of overall treatment, the total score of the OQ-45 was 19, with 15 for the SD subscale, 1 for the IR subscale and 3 for the SR subscale.

Figure 5. OQ-45: OUTCOME QUESTIONNAIRE

Discussion

To our knowledge, this is a first report on the physiological activity of the ANS during psychotherapy sessions leading to the experience of unconscious affects of murderous rage and guilt. Davanloo, with his technique of IS-TDP and an empirical approach, suggested the presence of a “neurobiological pathway” of unconscious murderous rage and guilt in individuals suffering from neurotic disorders. The “neurobiological pathway” of murderous rage manifests itself in the patient as a sensation of power, energy or heat that starts in the pelvis, spreads into the abdomen, chest, shoulders, arms and finally towards the hands (Davanloo, 2000). Patients sometimes describe a fireball, a volcano that wants to explode or violently unleash. Our study demonstrates that the experience of murderous rage in the transference in a patient describing the same neurobiological pathway (i.e. “heat in my chest”) is associated with an increased sympathetic activity (CSI), without necessarily an increased in heart rate. This finding is consistent with previous studies showing sympathetic activation with the experience of anger (Marci et al., 2007; McCraty et al., 1995).

Our hypothesis that specific feelings (anxiety, rage, and guilt) would be associated with distinct pattern of ANS activity was partially confirmed. Sympathetic activity fluctuated significantly during the two psychotherapeutic sessions. It increased initially to some degree with anxiety and then to a larger extent with rage. For guilt, however, the pattern of sympathetic activity differed between the two sessions. A recent study using functional infrared imaging (fIRI) showed that the experience of guilt in children (age: 39 to 42 months) was associated with sympathetic activity (Ioannou et al., 2013). In the same study, the experience of guilt was followed by a soothing phase involving a positive interaction with an adult and was associated with parasympathetic activity. The passage of guilt in a session of Davanloo’s ISTDP contains several dimensions such as an intense pain of having hurt a loved one, but also a feeling of love and bond with the attachment figure. According to Davanloo (Davanloo, 2005), the passage of unconscious guilt is experienced as physically painful at the level of the upper chest respiratory muscles. Since acute pain is associated with an increased in sympathetic activity (Terkelsen, Molgaard, Hansen, Andersen, & Jensen, 2005), it may partially explain that passage of unconscious guilt is associated with waves in the sympathetic nervous system as measured with CSI. In our case study, the activity of CSI appears more intense during session #5 compared to session #1; it is as if the passage of guilt became more painful or profound. Davanloo described that during treatment the patient undergoes “multidimensional unconscious structural changes” that take place at the three angles of the triangle of conflict (Davanloo, 2001). As the process goes on, the patient develops better tolerance to anxiety, improved defensive structure, and changes at the level of impulses and feelings, which allow the experience of more painful affects. It is also possible that our subject’s unconscious guilt was more intense for her mother than her father. Similar to the physiological findings of a “soothing phase” reported in children (Ioannou et al., 2013), we found some indication of increased vagal tone as indexed through RSA during reunification to the attachment figure following a breakthrough of guilt.

The polyvagal theory proposed that the mobilization system (e.g. fight or flight) depends on the functioning of the sympathetic nervous system (Porges, 2003b). Autobiographical recall of anger has been associated with an increased in sympathetic activity and left orbitofrontal cortex blood flow (Marci et al., 2007). Based on Davanloo’s technique of IS-TDP, Gaillard (Gaillard, 1987) hypothesized that neurosis results from disharmony in the coordination between the right brain, involved in the treatment of affective information and unacceptable buried feelings, and the left brain, which dominates behavioral control and interaction with the outside world. Gaillard proposed that the left brain sets into operation defense mechanisms to prevent the expression of the affective information coming from the right brain, which manifests itself in treatment as resistance. Our study supports the idea that through the mechanism of projection, or deceptive neuroception to use another construct, the neurotic individual perceives the therapist as a threat which triggers the mobilization system of fight or flight with its sympathetic arousal. As a consequence, the patient resorts to character defense mechanisms to avoid feelings from coming to the surface. For example, an obsessional character ruminates, rationalizes, or intellectualizes. Appropriate blockade of the patient’s character defense leads to a breakthrough of repressed rage, which was originally experienced towards an attachment figure. Davanloo’s IS-TDP would break through the cognitive resistance and reach the affective information coming from the right brain. Our results suggest that breaking through the unconscious affective zone using Davanloo’s technique is associated with variations in HRV, which is modulated primarily by the right hemisphere (Ahern et al., 2001).

Davanloo’s psychotherapeutic approach might contain key elements bridging attachment-based developmental neurobiology and psychodynamics. The phase of pressure to transference feelings is an attempt by the therapist to get emotionally close to the patient, an empathic invitation to share true feelings. For an individual with neurosis and unresolved childhood traumas, this emotional closeness, reminiscent of attachment relationships, triggers resistance. This resistance represents a rigid attractor state or frequently used network with specific patterns of neural firing associated with ways of thinking about the self and others (Westen & Gabbard, 2002), marked with distortion and projection. This rigid response comes from the left brain as an attempt to block the painful affective experience emanating from the right brain and to maintain the need for suffering imposed by unconscious guilt. At the physiological level, the patient is unable to connect affectively with the therapist, who is representing an attachment figure. The patient is prone to the mobilization system with a fight or flight response with arousal of the ANS.

Continued pressure to experience transference feelings creates a tension in the therapeutic process. Part of the patient is resisting the therapist, while another part wants to get close to the therapist and overcome the resistance. Davanloo’s technique of HOC with the resistance aims at resolving this tension and contains 16 interventions (Davanloo, 1999), among which pointing out the therapeutic task, stressing the patient’s will, clarifying the nature of the resistance and the patient’s potential. The HOC is an invitation for patient to listen to the inner self and experience true feelings. The proper application of the HOC helps the patient give up rigid resistance patterns and experience the affective unconscious, such as unacceptable aggressive impulses with their concomitant sympathetic activation. Following the breakthrough of murderous rage and with the experience of guilt, patients often retrieve memories of positive experiences with the attachment figure and recall feelings of love, despite previous empathic failure. Neurobiologically, the phenomena of reunification with the attachment figure may involve the SES, as described by Porges (Porges, 2003b). This neurobiological system depends on a functional vagal tone, which inhibits defensive response and allows flexibility in the regulation of various muscles (eyelids, facial expression, laryngeal and pharyngeal for vocalization, etc.) that are determinants for social behavior and autonomic control of the heart, creating a face-heart connection. In Davanloo’s IS-TDP patients experience eye contact with the attachment figure and recover repressed memories of positive experiences during the phase of forgiveness and through visual imagery. In our case study, this phase of the therapeutic process was associated with a relative increased in RSA when compared to the beginning of the session. If RSA represents a valid biomarker of self-regulation, our data suggests that Davanloo’s IS-TDP technique could bring rapid positive changes not only at the psychological level but also at the neurobiological level.

The main goal of our study was to examine the physiological response associated with Davanloo’s Central Dynamic Sequence in a typical session rather than monitor the process during the full course of treatment. It is still interesting to observe that following an initial symptomatic improvement in the first part of the treatment, the patient demonstrated some transitory returns of symptoms in the second phase of the therapy as suggested by the OQ-45 scores. Since that phase of the treatment focused on the patient’s mother, we explain this phenomenon by the activation of a normal grief reaction in someone who had unresolved issues towards the deceased. The proper application of Davanloo’s technique of IS-TDP can activate an acute grief reaction in cases of pathological mourning (Davis, 1988a, 1988b). Our patient spontaneously reported during treatment how she finally realized that her mother died. She also reported a shift in her dreams. For years, she had a recurrent dream involving a reunification with her mother as if she had not died. In the last phase of the treatment, she had dreams of going to her mother’s funeral. In between sessions, she reported intermittent sadness with anxiety symptoms, as seen in a normal grief reaction, but never to the level of functional impairment.

There are some limitations to this study. The data presented concern a single subject; therefore, we should avoid generalizations. We looked at two psychotherapy sessions, and we consider that much more insight would be gained from reviewing the full course of the therapy. In this study, we wanted to concentrate on the early part of the treatment, during which resistance is higher so that we could understand better the process of breaking through the unconscious at the physiological level. The patient presented suffered from a relatively mild neurotic illness; future research could help us determine if the observed phenomena apply to other conditions such as depression, somatisation or personality disorders. It is surprising that CVI did not demonstrate marked fluctuations during both sessions, while vagal tone—as indexed with RSA—showed interesting trends. The CVI and RSA measure some aspects of vagal activity, but they are not necessarily interchangeable (Allen et al., 2007). Unfortunately, there are no published data for short-term HRV measures obtained in a large population including adults aged less than 40 years (Nunan, Sandercock, & Brodie, 2010), and we could not compare our subject with normative data. Finally, our study design did not allow comparing HRV in our subject in an emotionally neutral condition as compared to the therapeutic setting.

Conclusion

This exploratory case study reports the physiological response of the ANS during two sessions of Davanloo’s IS-TDP in a case of panic disorder. We observed significant changes in heart-rate dynamics during a psychotherapeutic process leading to experience of unconscious affects of murderous rage and guilt, which were consistent with a developmental neurobiology model. Whether such responses from the ANS are specific to a certain psychotherapeutic technique or a certain population of patients, remain to be addressed.

(2012). Intensive short-term dynamic psychotherapy: a systematic review and meta-analysis of outcome research. Harvard Review of Psychiatry, 20, 97–108. doi:10.3109/10673229.2012.677347Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

(2001). Heart rate and heart rate variability changes in the intracarotid sodium amobarbital test. Epilepsia, 42(7), 912–921. doi: epi35400 [pii]Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

(2007). The many metrics of cardiac chronotropy: a pragmatic primer and a brief comparison of metrics. Biological Psychology, 74(2), 243–262. doi: S0301-0511(06)00186-4 [pii] 10.1016/j.biopsycho.2006.08.005Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

(2007). Borderline personality disorder and emotion regulation: insights from the Polyvagal Theory. Brain and Cognition, 65(1), 69–76. doi: S0278-2626(07)00063-2 [pii] 10.1016/j.bandc.2006.05.007Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

(2013). The effects of psychotherapy on brain function: A systematic and critical review. Progress in Neurobiology. doi: S0301-0082(13)00117-2 [pii] 10.1016/j.pneurobio.2013.10.006Medline, Google Scholar

(1999a). The “Perpetrator of the Unconscious” in Davanloo’s New Metapsychology. Part I: Review of Classic Psychoanalytic Concepts. International Journal of Intensive Short-Term Dynamic Psychotherapy, 13(3), 151–157.Crossref, Google Scholar

(1999b). The “Perpetrator of the Unconscious” in Davanloo’s New Metapsychology. Part II: Comparison of the Perpetrator to Classic Psychoanalytic Concepts. International Journal of Intensive Short-Term Dynamic Psychotherapy, 13(3), 159–176.Crossref, Google Scholar

(1999c). The “Perpetrator of the Unconscious” in Davanloo’s New Metapsychology. Part III: Specifics of Davanloo’s Technique. The “Perpetrator of the Unconscious’ in Davanloo’s New Metapsychology. Part III: Specifics of Davanloo’s Technique., 13(3), 177–189.Google Scholar

(2005). Low heart rate variability and the effect of depression on post-myocardial infarction mortality. Archive of Internal Medicine, 165(13), 1486–1491.Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

(2000). Autonomic dysregulation in panic disorder and in post-traumatic stress disorder: application of power spectrum analysis of heart rate variability at rest and in response to recollection of trauma or panic attacks. Psychiatry Research, 96(1), 1–13.Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

(1996). The somatic marker hypothesis and the possible functions of the prefrontal cortex. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London B: Biological Sciences, 351(1346), 1413–1420. doi: 10.1098/rstb.1996.0125Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

(1990). Unlocking the Unconscious. Chichester, England.: John Wiley and Sons.Google Scholar

(1999). Intensive short-term dynamic psychotherapy - central dynamic sequence: head-on collision with resistance. International Journal of Intensive Short-Term Dynamic Psychotherapy, 13, 263–282.Crossref, Google Scholar

(2000). Intensive Short-Term Dynamic Psychotherapy - Selected Papers of Habib Davanloo. Md. Chichester, England.: John Wiley and Sons.Google Scholar

(2001). Intensive short-term dynamic psychotherapy - extended major direct access to the unconscious. European Journal of Psychotherapy, 2(2).Google Scholar

(2005). “Intensive Short-Term Dynamic Psychotherapy” Kaplan H.Sadock B. (eds), Comprehensive Textbook of Psychiatry (8th Edition ed., Vol. 2, pp. 2628–2652). Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins.Google Scholar

(1988a). Transformation of pathological mourning into acute grief with intensive short-term dynamic psychotherapy. International Journal of Short-Term Psychotherapy, 3, 79–97.Google Scholar

(1988b). Transformation of pathological mourning into acute grief with intensive short-term dynamic psychotherapy. Part II. International Journal of Short-Term Psychotherapy, 3, 279–298.Google Scholar

(1992). An argument for basic emotions. Cognition and Emotion, 6(3), 169–200. doi: 10.1080/02699939208411068Crossref, Google Scholar

(1957). On narcissism, an introduction. In Strachey (Ed. & Trans.), The standard edition of the complete psychological works of Sigmund Freud (Vol. 14, pp 73–102). (Original work published 1941)Google Scholar

(1987). Implications of Brain Lateralization for Intensive Short-Term Dynamic Psycho-therapy. International Journal of Intensive Short-Term Dynamic Psychotherapy, 2, 79–97.Google Scholar

(2013). The autonomic signature of guilt in children: a thermal infrared imaging study. PLoS One, 8(11), e79440. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0079440 PONE-D-13-11602 [pii]Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

(1995). Altered heart rate variability in panic disorder patients. Biological Psychiatry, 37(1), 18–24.Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

(2013). Multivariate pattern classification reveals autonomic and experiential representations of discrete emotions. Emotion, 13(4), 681–690. doi: 2013-10201-001 [pii] 10.1037/a0031820Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

(1996). Administration and Scoring Manual for the Outcome Questionnaire (OQ-45.2). Wilmington, DE: American Professional Credentialing Services LLC.Google Scholar

(1996). Outcome Questionnaire (OQ-45.2). Stevenson, MD: American Professional Credentialing Services.Google Scholar

(2007). Autonomic and prefrontal cortex responses to autobiographical recall of emotions. Cognitive, Affective & Behavior Neuroscience, 7(3), 243–250.Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

(1995). The effects of emotions on short-term power spectrum analysis of heart rate variability. American Journal of Cardiology, 76(14), 1089–1093. doi: S0002914999803099 [pii]Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

(2005). Cardiac Vagal Tone, defensiveness, and motivational style. Biological Psychology, 68(2), 147–162. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsycho.2004.03.019 S030105110400095X [pii]Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

(1998). The relationship of depression to cardiovascular disease: epidemiology, biology, and treatment. Archive of General Psychiatry, 55(7), 580–592.Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

(2010). A quantitative systematic review of normal values for short-term heart rate variability in healthy adults. Pacing Clinical Electrophysiology, 33(11), 1407–1417. doi: PACE2841 [pii] 10.1111/j.1540-8159.2010.02841.xCrossref, Medline, Google Scholar

(1995). Orienting in a defensive world: Mammalian modifications of our evolutionary heritage. A Polyvagal Theory. Psychophysiology, 32(4), 301–318.Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

(2003a). The Polyvagal Theory: Phylogenetic contributions to social behavior. Physiology & Behavior, 79(3),503–513. doi: S0031938403001562 [pii]Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

(2003b). Social engagement and attachment: a phylogenetic perspective. Annals of the N Y Academy of Science, 1008, 31–47.Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

(1997). Early organization of the nonlinear right brain and development of a predis-position to psychiatric disorders. Developmental Psychopathology, 9(4), 595–631.Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

(2000). Attachment and the regulation of the right brain. Attachment and Human Development, 2(1), 23–47. doi: 10.1080/146167300361309Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

(2009). Relational trauma and the developing right brain: an interface of psychoanalytic self-psychology and neuroscience. Annals of the N Y Academy of Science, 1159, 189–203. doi: NYAS04474 [pii] 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2009.04474.xCrossref, Medline, Google Scholar

(1998). The Mini-International Neuropsychiatric Interview (M.I.N.I.): the development and validation of a structured diagnostic psychiatric interview for DSM-IV and ICD-10. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, 59 Suppl 20, 22–33; quiz 34-57.Medline, Google Scholar

(2005). Acute pain increases heart rate: differential mechanisms during rest and mental stress. Autonomic Neuroscience, 121(1-2), 101–109. doi: S1566-0702(05)00154-2 [pii] 10.1016/j.autneu.2005.07.001Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

(1996). Autonomic characteristics of generalized anxiety disorder and worry. Biological Psychiatry, 39(4), 255–266.Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

(2000). A model of neurovisceral integration in emotion regulation and dysregulation. J Affect Disord, 61(3), 201–216. doi: S0165032700003384 [pii]Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

(1997). A new method of assessing cardiac autonomic function and its comparison with spectral analysis and coefficient of variation of R-R interval. Journal of Auton Nervous System, 62(1-2), 79–84.Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

(2013). Effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of Davanloo’s intensive short-term dynamic psychotherapy: does unlocking the unconscious make a difference? American Journal of Psychotherapy, 67(1), 89–108.Link, Google Scholar

(2002). Developments in cognitive neuroscience: I. Conflict, compromise, and connectionism. Journal of the Am Psychoanalytic Association, 50(1), 53–98.Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar