Naturalistic Outcomes of Evidence-Based Therapies for Borderline Personality Disorder at a Medical University Clinic

Abstract

Dialectical behavior therapy (DBT) and dynamic deconstructive psychotherapy (DDP) are listed in the National Registry of Evidence-Based Programs and Practices based on their performances in randomized controlled trials. However, little is known about their effectiveness in real-world settings. In the present study, the authors observed the naturalistic outcomes of 68 clients with borderline personality disorder (BPD) who were treated at a medical university clinic by experienced therapists using either comprehensive DBT (n = 25) or DDP (n = 27), with 16 clients treated with unstructured psychotherapy serving as a control. We found both DBT and DDP achieved significant reductions in symptoms of BPD, depression, and disability by 12 months of treatment, and showed effect sizes consistent with controlled trials. However, attrition from DBT was high and DDP obtained better outcomes than DBT (d = .53). Larger effectiveness studies are needed to replicate these findings, delineate common and unique treatment processes, and determine therapist and patient characteristics predicting positive outcomes.

Introduction

Several manual-based treatments for borderline personality disorder (BPD) have been developed and have demonstrated efficacy in controlled trials (Bateman & Fonagy, 2004; Blum et al., 2008; Clarkin et al., 2007; Giesen-Bloo et al., 2006; Gregory & Remen, 2008; Linehan et al., 2006).

The most widely applied modality, Dialectical Behavior Therapy (DBT), has demonstrated superior outcomes to unstructured therapies in numerous randomized controlled trials (Koons et al., 2001; Linehan et al., 1991; van den Bosch et al., 2002; Verheul et al., 2003). In large controlled trials, it has also been shown to have better outcomes than psychotherapy delivered by experts (Linehan et al., 2006) and generally equivalent outcomes to other structured treatments for BPD (Clarkin et al., 2007; McMain et al., 2012). Given these positive findings, DBT has been widely applied in clinical settings.

Dynamic Deconstructive Psychotherapy (DDP) is a newer treatment with demonstrated efficacy, but has been applied less extensively. In a previous 12-month controlled trial, 30 subjects with BPD and co-occurring active alcohol use disorders were randomized to either DDP or optimized community care for 12 months, and evaluated after an additional 18 months of naturalistic care in the community (Gregory et al., 2008; Gregory et al., 2010). In applying treatment to this low-functioning and highly comorbid BPD population, DDP demonstrated relatively good retention and large between-group treatment effects for core symptoms of BPD, as well as for depression, parasuicidal behavior, alcohol misuse, recreational drug use, inpatient care, and perceived social support.

Subsequent research on the process mechanisms of this study indicated that adherence to DDP technique strongly correlated with positive outcome (Goldman & Gregory, 2009) and that specific outcomes were associated with the application of specific techniques (Goldman & Gregory, 2010). After an independent review by the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, DDP was included on its National Registry of Evidence-Based Programs and Practices (www.nrepp.samhsa.gov).

Although controlled trials have identified promising treatment modalities for BPD, such studies may provide unrealistic estimates of treatment effects given the structured nature of controlled research designs, potential study-selection bias for subjects with low comorbidity to ensure sample homogeneity and responsiveness, self-selection bias for subjects motivated to undergo extensive research protocols, and therapist allegiance to the investigational treatment (Luborsky et al., 1999; Stirman et al., 2003). To determine optimal allocation of scarce treatment resources, research is necessary to evaluate the effectiveness of evidence-based treatments in real world settings; yet, this type of research has been sparse.

With the exception of case reports, there have been no observational studies of DDP in real-world settings. To the authors’ knowledge, there have been only two published observational outpatient studies of comprehensive DBT for clients with BPD. Comtois and colleagues (2007) reported that 23 self-injuring women who completed a year of treatment with comprehensive DBT at a community mental health center had significant reductions in inpatient admissions, but no change in self-injury or emergency room visits. Limitations of this study include substantial modifications to typical DBT protocol, exclusion of clients with co-occurring bipolar disorder, psychosis, or substance use disorders, lack of a control treatment comparison, no symptom measures, no intent-to-treat analysis, and highly skewed data violating assumptions of the t-statistic.

In the second study, Harley and colleagues (2007) examined the naturalistic outcomes of 49 clients receiving comprehensive DBT or DBT skills group at a university medical clinic. Outcomes were measured at seven months (one cycle of the skills group). Clients completing treatment demonstrated significant improvement across a broad array of self-reported symptoms, but attrition was high. The study had several strengths, including limited exclusion criteria, use of validated instruments, and careful accounting of potential confounding variables. Study limitations were statistical analysis of completers only and lack of independent verification of adherence to DBT protocols.

The present paper adds to the naturalistic BPD treatment studies by observing the outcomes, over 12 months, of two manual-based treatments—DBT and DDP—in a medical university clinic. A third group of clients received unstructured eclectic individual psychotherapy and served as a control. The primary aim was to evaluate the effectiveness of the two structured treatments in a setting in which clients often have high comorbidity and a treatment-refractory course of illness. The utilization of two evidence-based therapies within the same treatment setting provides a unique opportunity to compare and contrast how these models perform in the real world without the selection biases inherent in study recruitment.

Method

Participants

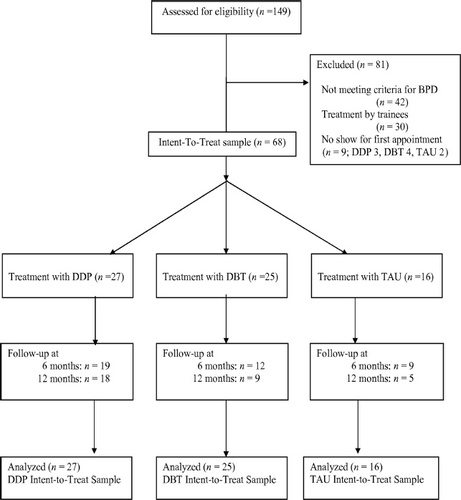

The participants in this study included 68 clients with BPD who started treatment with an expert therapist at the Center for Emotion and Behavior Integration (CEBI) between June of 2008 and June of 2011. The Center for Emotion and Behavior Integration is a specialized tertiary care program within a medical university clinic serving a five-county region and offers two evidence-based modalities: DBT and DDP. The Center for Emotion and Behavior Integration targets adults with dysfunctional behaviors, including addictions, BPD, eating disorders, self-injury, and recurrent suicide attempts. Clients diagnosed with schizophrenia, intellectual disabilities, or dementia are not eligible for this program. Figure 1 provides a flow diagram of recruitment and retention of participants in the study.

Figure 1. Recruitment and Retention of Participants

Table 1 displays pretreatment characteristics of the intent-to-treat (ITT) sample. Most of the clients (82%) had been referred from other therapists or institutions because of poor response to previous trials of psychotherapy and medications. The sample had high comorbidity with Axis I disorders, including alcohol and drug use disorders. Specific recreational drugs used by the sample within the past 6 months included cannabis (n = 20), opiates (n = 9), amphetamines (n = 4), benzodiazepines (n = 4), and cocaine (n = 3). The ages ranged from 18 to 58 years.

| Characteristic | DDP (n= 27) | DBT (n= 25) | TAU (n= 16) | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age – years | 28.0 ± 11.7 | 36.6 ± 10.2 | 29.3 ± 11.5 | .02 |

| Gender Male | 4 (15) | 4 (16) | 5 (31) | |

| Female | 23 (85) | 21 (84) | 11 (69) | .37 |

| Marital Status | ||||

| Single | 21 (78) | 13 (52) | 12 (75) | |

| Other | 6 (22) | 12 (48) | 4 (25) | .15 |

| Gainful Employment | ||||

| Full or Part-time | 11 (41) | 9 (36) | 4 (25) | |

| None | 16 (59) | 16 (64) | 12 (75) | .58 |

| Race/Ethnicity | ||||

| Caucasian | 24 (89) | 21 (84) | 15 (94) | |

| Other | 3 (11) | 4 (16) | 1 (6) | .63 |

| Substance Use Disorders | ||||

| Alcohol | 14 (52) | 7 (28) | 7 (44) | .21 |

| Drug | 12 (44) | 8 (32) | 5 (31) | .57 |

| Eating Disorders | 9 (33) | 5 (20) | 9 (56) | .06 |

| Depressive Disorders | ||||

| Major Depression | 18 (67) | 20 (80) | 9 (56) | .36 |

| Other | 11 (41) | 11 (44) | 11 (69) | .18 |

| Anxiety Disorders | ||||

| Panic Disorder | 10 (37) | 9 (36) | 7 (44) | .87 |

| PTSD | 7 (26) | 11 (44) | 7 (44) | .32 |

| Other | 12 (44) | 11 (44) | 11 (69) | .26 |

Table 1. Characteristics of the Sample

There were no significant differences among the three treatment groups at baseline in regards to diagnoses, outcome measures, or demographics, except age. To ascertain whether age was related to change for the primary outcome measure (BEST), we conducted a multiple regression analysis with baseline BEST scores in the first block of predictors and age in the second block, with 12-month BEST scores as the dependent variable. Controlling for baseline BEST scores, age did not significantly predict 12-month BEST scores, R2 change = .000, p = .99. The same procedure was carried out for all other outcome measures, and in no case did age significantly predict outcome.

Assessment Procedure

All clients seeking treatment at CEBI undergo an extensive intake protocol. Clients complete an intake packet containing administrative forms and self-rated instruments to assess severity and suitability for treatment at CEBI. Once clients are assigned a therapist, they meet with a graduate student in clinical psychology for a prescreening evaluation, which includes reviewing self-rated instruments for completeness and administering the BPD section of the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis II Personality Disorders (SCID-II; First et al., 1997) and the Individual Assessment Profile (IAP; Flynn et al., 1995). The IAP is a structured interview that quantifies alcohol and recreational drug use over lifetime, six-month, and previous 30-day periods. The clinical coordinator reviews the interviews with the Director of CEBI and writes up a summary of the questionnaires and interviews. This summary is then provided to the therapists (both within and outside of CEBI) involved in the care of that particular client.

The specific self-rated intake and outcome measures include:

Borderline Evaluation of Severity over Time ([BEST] Pfohl, Blum, St. John, McCormick, Allen, et al., 2009)

We chose the BEST as our primary measure for assessing improvement. The BEST is a 15-item, self-report questionnaire designed to assess change in the severity of BPD during the prior month, including thoughts, feelings, and behaviors. Items are rated on a Likert-type scale and cluster into three subscales: thoughts and feelings (e.g., mood reactivity, feelings of emptiness, suicidal thinking), negative behaviors (e.g., self-injury), and positive behaviors (e.g., following through on therapy plans). Total scores range from twelve to 72, with higher scores indicating greater severity. The BEST has shown good internal consistency (α = .92), test-retest reliability (r = .62), convergent validity, sensitivity to clinical change, and distinguishes well between those with and without BPD (Pfohl et al., 2009).

Psychiatric Diagnostic Screening Questionnaire ([PDSQ] Zimmerman & Mattia, 2001)

This self-rated instrument reliably screens for common Axis I disorders, including depressive disorders, anxiety disorders, eating disorders, and alcohol and drug use disorders. The PDSQ diagnoses are displayed in Table 1. The PDSQ does not reliably screen for other diagnoses, such as bipolar disorder or attention deficit disorder.

Beck Depression Inventory ([BDI] Beck et al., 1961)

The BDI is a 21-item measure with scores ranging from 0 to 63. It has been used in previous treatment trials of BPD (Gregory et al., 2010), demonstrated good internal consistency (α = .93), and acceptable sensitivity and specificity in detecting clinical depression (Golden et al., 2007).

Sheehan Disability Scale ([SDS] Sheehan, Harnett-Sheehan, & Raj, 1996)

The SDS is a brief self-report instrument developed to assess functional impairment across three domains: work/school, social, and family. We averaged the three domain scores for each client. The SDS has been found to have good internal reliability (α = .83), to correlate with other measures of functional disability, and to discriminate clients with mental disorders from those with chronic medical conditions (Luciano et al., 2010).

Suicidal Behaviors Questionnaire ([SBQ] Marsha M. Linehan, unpublished manuscript, 1981)

The SBQ is a self-rated version of the Lifetime Parasuicide Count (Comtois & Linehan, 1999) modified to assess both suicidal ideation and the frequency of various parasuicidal behaviors (overdoses, cutting, burning, etc.) during the previous 30 days. Clients are instructed to rate whether each act was “intending to die,” “ambivalent,” or “not intending to die.” Employing a procedure recommended by O’Carroll and colleagues (1996), parasuicide episodes elicited by the SBQ can be categorized as either non-suicidal self-injury (“not intending to die”) or suicide attempts (“ambivalent” or “intending to die”). The SBQ was found to be a sensitive measure of change for women with BPD and recent parasuicide behaviors in a large randomized controlled trial of DBT (Linehan et al., 2006).

At six and 12 months, therapists provide clients with a packet of self-rated outcome measures (BEST, BDI, SDS, SBQ) and ask them to bring the completed packet to the next session. The packets are then scored by the Center secretary, entered into a clinical database, summarized for the therapist to review with the client, and shared with the Director for quality assurance purposes.

Treatments

The CEBI offers three main treatment protocols for clients seeking treatment there:

| • | DBT (which is comprehensive. including both individual therapy and skills group provided by CEBI therapists), | ||||

| • | DDP (provided by CEBI therapists), and | ||||

| • | DBT skills group only (provided by CEBI therapists to supplement weekly individual therapy provided by an outside referring therapist). | ||||

Assignment to these different treatment models is based on client preferences and therapist availability, according to a telephone protocol followed by the intake secretary. During the three-year study period, 27 participants were assigned to DDP and 25 to comprehensive DBT. However, eight participants were assigned to other licensed therapists within the university because qualified therapists for DDP and DBT were not readily available. These faculty therapists had at least four years of post-licensure clinical experience and provided unstructured psychody-namically oriented weekly individual therapy. An additional eight participants were referred by therapists outside the CEBI for DBT skills group only. As condition for acceptance into the skills group only, the client had to meet individually with an outside therapist at least once a week. The outside therapists had diverse theoretical orientations, ranging from cognitive behavioral to psychodynamic to eclectic. A control group of 16 participants labeled treatment as usual (TAU) was comprised of participants assigned to licensed therapists within the university for unstructured psychodynamic therapy (n = 8) and those referred by an outside therapist to the DBT skills group only (n = 8).

Dynamic deconstructive psychotherapy postulates that BPD is the result of a deficit in emotion processing, along with a defensive reaction to an embedded sense of badness. Treatment involves weekly individual sessions over a 12-month period and combines elements of translational neuroscience, object relations theory, and deconstruction philosophy (Gregory & Remen, 2008). Techniques include verbal elaboration of recent interpersonal encounters and maladaptive behaviors, identification of specific emotions associated with these episodes, and assistance in helping clients identify, acknowledge, and bear unconscious conflicts and unresolved losses. In addition, therapists provide novel experiences in the client-therapist relationship that deconstruct clients’ basic assumptions about themselves and others, support individuated relatedness, and restore ruptures to the alliance (Gregory, 2005, 2007). Limited telephone contact is permitted outside of sessions for rescheduling and crisis-management. The treatment manual is available online at www.upstate.edu/ddp.

The three DDP therapists included the founder of this method of therapy (RG; n = 9). The two other psychiatrists had undergone one-year fellowships in DDP and had four to five years of experience in practicing, supervising, and teaching DDP. The three therapists met on a weekly basis to ensure treatment fidelity. Six clients (22%) undergoing DDP also received weekly group psychotherapy, in either an interpersonally-oriented group (n = 3), a DBT skills group (n = 2), or an eating disorders group (n = 1).

Dialectical behavior therapy postulates that BPD is caused by a deficit in emotion regulation. It consists of a manual-based cognitive-behavioral treatment involving weekly one-hour individual and two-hour group sessions (Linehan, 1993). The primary goal of treatment is elimination of behavioral dyscontrol by helping clients develop more effective coping strategies for emotion regulation. The treatment involves diverse strategies, such as mindfulness, the helping relationship, validation and empathy, contingency management, exposure, behavioral analysis, and dialectical strategies. These are organized according to a hierarchy of targets, prioritizing management of suicidal and self-damaging behaviors, and balancing validation with behavioral change interventions. Clients are also encouraged to call for skills coaching during crises.

Although both DDP and DBT activate autobiographical memory by reviewing specific emotionally charged incidents and behaviors both within and between sessions, the therapist stance differs substantially. Whereas the DDP therapist tries to be nondirective and exploratory to support individuation, the DBT therapist tries to be validating, directive, educative, and pragmatic.

One of the two DBT therapists included a nurse practitioner who specialized in this therapy. This provider had intensive training in DBT, regular attendance at DBT conferences, 14 years of experience in treating clients with BPD as a member of an intensively trained team, and gave presentations of DBT locally, regionally, and nationally. The second provider was a clinical psychologist with intensive training in DBT and four years of postgraduate experience using DBT with clients who had BPD. To ensure treatment fidelity both therapists participated in a weekly DBT consultation group with other DBT therapists.

Medication management was provided by the nurse practitioner for all DBT clients and by each of the DDP therapists for their own clients. The use of medication in both treatment arms followed American Psychiatric Association guidelines (American Psychiatric Association, 2001) and was conservative, consistent with recent meta-analyses indicating small treatment effects overall for symptom management with medication (Lieb, Vollm, Rucker, Timmer, & Stoffers, 2010). Medication management for TAU clients was provided by psychiatrists in the community.

Statistical Analyses

Upon approval of our institutional review board, we extracted from our clinical database a de-identified sample of 68 participants for intention to treat (ITT) analysis of 12-month outcomes. The 68 participants included all clients who had been screened for admission to CEBI from June 2009 through January 2011, met diagnostic criteria for BPD according to the SCID-II interview, and attended at least the first treatment session. The sample excluded clients treated by trainees (see Figure 1).

For BEST scores and secondary outcome measures that met the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test of normality, we compared treatment effectiveness between groups by conducting univariate analysis of covariance (ANCOVA) on 12-month scores, controlling for pretreatment scores. For those outcome variables with skewed distributions, we utilized Mann-Whitney U tests of between-group differences in change scores (baseline to 12 months). We utilized paired t-tests and Wilcoxon signed-rank tests for pre-post differences. Demographic and clinical characteristics of treatment groups were compared using three-way ANOVA or chi-square tests. A significance level of α = .05 was used for all statistical comparisons (two-tailed). Missing data points were accounted for conservatively by carrying forward the most recent observation to subsequent data collection intervals.

We computed pre–post effect sizes as the difference between pretreatment and 12-month means divided by the pooled standard deviation (Cohen, 1992). To estimate between-group effect sizes, we calculated the group difference in mean improvement over 12 months divided by the pooled standard deviation. Cohen suggested that effect sizes greater than .20, .50, and .80 be interpreted as “small,” “medium,” and “large,” respectively.

Results

Primary Outcome

Treatment outcomes within and between groups are reported in Table 2. Clients treated with either DDP or DBT improved significantly on the BEST over 12 months (t = 4.90, df = 26, p = .000; t = 3.02, df = 24, p = .006, respectively). Pre-post effect sizes for treatment completers were large for both DDP (d = 2.38) and DBT (d = 1.24).

| Outcome Measures | DDP | DBT | TAU | DDP vs TAU | DBT vs TAU | DDP vs DBT | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean ± SD | Mean ± SD | Mean ± SD | F | p | d | F | p | d | F | p | d | |

| BEST | ||||||||||||

| Pretreatment | 47.1 ± 9.4 | 49.2 ± 13.1 | 45.5 ± 12.6 | |||||||||

| 6 months | 36.9 ± 10.8 | 44.7 ± 15.4 | 45.3 ± 10.9 | |||||||||

| 12 months | 33.0 ± 12.1‡ | 41.8 ± 16.5† | 42.9 ± 13.6 | 8.37 | .006 | 1.01 | 1.56 | .219 | .35 | 4.37 | .042 | .53 |

| BDI | ||||||||||||

| Pretreatment | 29.7 ± 11.6 | 33.1 ± 9.0 | 30.2 ± 14.7 | |||||||||

| 6 months | 19.6 ± 11.0 | 28.4 ± 12.2 | 29.5 ± 14.1 | |||||||||

| 12 months | 17.1 ± 11.5‡ | 27.6 ± 13.7† | 29.6 ± 14.7 | 14.84 | .000 | .96 | 4.35 | .044 | .39 | 7.47 | .009 | .63 |

| SDS | ||||||||||||

| Pretreatment | 6.3 ± 1.7 | 7.4 ± 1.7 | 6.4 ± 2.8 | |||||||||

| 6 months | 5.0 ± 2.3 | 6.3 ± 2.8 | 7.0 ± 2.1 | |||||||||

| 12 months | 3.8 ± 2.4‡ | 6.1 ± 3.0† | 7.0 ± 2.3 | 18.48 | .000 | 1.41 | 3.61 | .065 | .80 | 4.07 | .049 | .56 |

| U | p | Z | U | p | Z | U | p | Z | ||||

| Self-Injuries | ||||||||||||

| Pretreatment | 2.1 ± 3.5 | 2.1 ± 3.2 | 1.6 ± 2.9 | |||||||||

| 6 months | 1.2 ± 2.8 | 2.2 ± 3.2 | 1.4 ± 1.7 | |||||||||

| 12 months | 1.3 ± 2.6* | 2.4 ± 3.6 | 1.8 ± 2.8 | 193 | .46 | .75 | 175 | .30 | 1.04 | 253 | .02 | 2.35 |

| Suicide Attempts | ||||||||||||

| Pretreatment | 1.1 ± 2.7 | 1.4 ± 2.8 | 1.4 ± 3.4 | |||||||||

| 6 months | .52 ± 1.9 | 1.4 ± 2.8 | 1.5 ± 3.5 | |||||||||

| 12 months | .56 ± 1.9 | 1.3 ± 2.8 | 1.5 ± 3.5 | 194 | .39 | .86 | 186 | .47 | .73 | 323 | .65 | .45 |

Table 2. Outcomes by Treatment Group Over 12 Months

Clients receiving TAU did not improve over 12 months of treatment (t = 1.30, df = 15, p = .213). Within TAU, there was a small, nonsignificant effect favoring unstructured psychodynamic therapy alone over DBT skills group with a therapist outside of CEBI who used eclectic individual therapy (d = .22).

The ANCOVA analyses by group in the ITT cohort indicated that DDP achieved statistically significantly greater improvement in mean BEST scores than did DBT. Treatment effects of DDP were large relative to TAU and medium relative to DBT (see Table 2). We used a cut-off suggested by Blum and colleagues (2002), and we classified clients as having achieved a clinical response to treatment if their BEST scores decreased at least 25% from baseline. By using this cut-off, 16 (89%) clients completing 12 months of DDP responded to treatment, compared to six (67%) clients who completed DBT and two clients (40%) who completed TAU. The absolute difference in the response rates between DDP and DBT completers was a number-needed-to-treat of five, which was not statistically significant (X2 = .39, df = 1, p = .535).

Secondary Outcomes

As shown in Figure 1, 32 clients in the sample (47%) completed one year of treatment. There were no significant differences at baseline on any outcome measure between those clients who completed 12 months of treatment and those who prematurely left treatment. Eighteen clients (67%) receiving DDP completed treatment, which is better than the retention rate of 36% (n = 9) for clients receiving DBT (X2 = 4.89, df = 1, p = .027) and the retention rate of 31% (n = 5) for clients receiving TAU (X2 = 5.07, df = 1,p = .024). Six-month retention rates were 70%, 48%, and 56% for DDP, DBT, and TAU, respectively, and did not significantly differ between groups.

Clients receiving the manual-based treatments (DDP and DBT) achieved significant improvement over time in depression (t = 5.00, df = 26, p = .000; t = 3.30, df = 24, p = .003, respectively) and disability (t = 4.65, df = 26, p = .000; t = 2.87, df = 24, p = .008, respectively). Clients receiving DDP also achieved significant improvement over time in self-injury, though this data was highly skewed. Clients receiving TAU showed no significant improvement over time on any secondary outcome measure. No treatment group demonstrated statistically significant improvement in the rate of suicide attempts over time.

As Table 2 indicates, DDP demonstrated significantly greater improvement in depression and disability than either of the other two treatments, with medium to large treatment effects, and greater improvement in self-harm than DBT. DBT achieved significantly greater improvement in depression than TAU, and trended towards greater improvement in disability. Utilizing a cut-off of 50% improvement on BDI scores as a marker for clinical response (Riedel et al., 2010), 13 clients (72%) completing 12 months of DDP achieved a clinical response in depression severity, compared to 4 clients (44%) completing DBT and 1 client (20%) completing TAU.

Discussion

The primary finding from this study is that structured, manual-based treatments can be effective for treatment-refractory clients with BPD within a real world setting of a medical university clinic. Clients receiving either DDP or comprehensive DBT demonstrated significant improvement in symptoms of BPD over time in the intent-to-treat sample. The magnitude of the treatment effects for DDP and DBT in this naturalistic study were similar to those reported in randomized controlled trials of these modalities. Öst (2008) performed a meta-analysis of controlled trials of DBT. Across those studies, the mean effect size of DBT was .58 as compared to control treatments. In the present study, the mean effect size for DBT vs. TAU comparisons across BEST, BDI, and SDS over 12 months was .51 using similar methodology. However, the attrition rate of DBT in the present study was higher than those reported in most previous studies of BPD, which averaged 39.1% (weighted mean) over 12 months (Öst, 2008). It is possible that at our clinic, DBT was not practiced in a way that fostered high retention. Alternatively, the high attrition rate may have been a consequence of the study’s naturalistic design. A large meta-analysis indicated that randomized controlled trials of psychotherapy have significantly lower attrition than observational studies in real world settings (Swift & Greenberg, 2012). The rigors of randomized controlled studies may self-select for more compliant and highly motivated clients.

As was the case with DBT, the treatment effects of DDP in the present study were similar to those reported previously. In a randomized controlled trial of DDP for clients with co-occurring BPD and alcohol use disorders (Gregory et al., 2008, 2010), the mean between-group treatment effect of DDP vs. TAU was d = .90 for BEST, BDI, and SDS at 12 months. In the present study, the mean between-group treatment effect for those three variables was d = 1.13. The slightly higher treatment effect for DDP in the present study may be a consequence of expert therapists, as compared to primarily trainee therapists in the previous study (Deranja, Manring, & Gregory, 2012). In both studies, the 12-month attrition rate was 33%, and approximately 90% of clients who stayed in treatment achieved a clinical response in BPD symptoms (Gregory et al., 2010).

The finding of better outcomes with structured treatments compared to TAU is consistent with controlled trials for BPD (Gregory et al., 2008; Linehan et al., 1991; Verheul et al., 2003). This finding may indicate that certain structured, specialized treatments are more effective than TAU, or it may indicate that clients benefit from having therapists who have 1) a high allegiance to their treatment models (Luborsky et al., 1999), 2) more experience treating clients with BPD, or 3) higher morale from ongoing support.

An unexpected finding in the study was the outcomes of clients treated with DDP achieved greater improvement in core symptoms of BPD and in depression, disability, and self-injury than clients treated with comprehensive DBT. This finding is particularly surprising given that the study was powered to detect only medium-to-large treatment effects and that the treatment intensity of DDP was generally less than that of DBT; therefore, the finding requires some explanation. The most obvious possible explanation is that DBT was not practiced in a competent manner. This explanation is supported by the relatively high attrition of clients receiving DBT and the lack of independent ratings for therapist adherence to DBT; however, undermining this argument is that the treatment effects of DBT as compared to TAU were similar to those reported in previous clinical trials (see above),and that the only other published naturalistic study of DBT in a university medical clinic reported similarly high attrition (Harley, Baity, Blais, &Jacobo, 2007). In an observational treatment study of BPD at Massachusetts General Hospital’s clinic in Boston, Harley and colleagues (2007) reported that 49% of clients completed a seven-month cycle of DBT, which is very similar to the six-month retention rate of 48% for DBT found in the present study. Moreover, their pre–post effect sizes for symptoms of BPD and depression after completing seven months of DBT were d = .83 and .72, respectively. Despite using different outcome measures, these effect sizes are similar to the present study’s pre-post effect sizes for symptoms of BPD (d = .75) and depression (d = 1.07) after completing six months of comprehensive DBT. Nevertheless, the absence of formal measurements of DBT adherence in both the present study and in the study by Harley and colleagues (2007) makes it impossible to rule out poor adherence to technique as a contributor to DBT’s high attrition rate.

A second possible explanation for the differences in outcome between DDP and DBT in the present study is design limitations. Naturalistic studies offer some advantages over randomized controlled trials in that they avoid selection bias inherent in subject recruitment and consent procedures, eschew extrinsic incentives for remaining in a study, and are less likely to influence therapist practice during the study (Stirman et al., 2003). On the other hand, naturalistic studies are less able to measure and control for potentially confounding variables. In the present study, for example, the presence of co-occurring Axis II disorders, bipolar disorder, and attention deficit disorder were not systematically assessed. The varying rates of eating disorders among the treatment groups may also have influenced outcomes. Moreover, it is possible that the presence of the founder of DDP created additional allegiance effects in that treatment arm. Exclusive reliance on self-rated outcome measures, lack of control for medication effects, the use of relatively few therapists, and a relatively small study population that was predominantly Caucasian are other limitations. The latter two factors may limit the ability of the findings to be generalized to other settings.

It is possible that DDP may be especially helpful for certain clients who have highly comorbid BPD and are difficult to engage in therapy. In the treatment of clients severely impaired by BPD with active substance use disorders or dissociative identity disorder, DDP has demonstrated strongly positive outcomes (Chlebowski and Gregory, 2012; Gregory et al., 2008; Gregory et al., 2010). Improvement in disability reported by clients receiving DDP is encouraging since longitudinal studies of BPD have demonstrated disappointing results in this domain (McMain et al., 2012; Zanarini et al., 2012). However, the relatively small size of studies evaluating DDP up to this point precludes firm conclusions in this regard.

The present study provides the opportunity to observe and to compare the naturalistic course of specialized, structured treatments in a real-world setting to unstructured treatments of similar intensity. Some strengths of the present study’s design are its quasi-randomized assignment, use of well-trained and experienced therapists who had high allegiance to their particular treatment models, weekly consultation groups to maintain fidelity to the treatment models, structured interviews to diagnose BPD, clear inclusion and exclusion criteria, and the use of validated outcome measures (Leichsenring, 2004).

Despite its strengths, the present study has important limitations, and replication of the study’s findings is needed before clear conclusions can be drawn. Further research is warranted regarding the relative effectiveness of evidence-based treatments in real world settings. It is also likely that DBT and DDP each offers advantages for different client characteristics, and research is needed to delineate common and unique treatment processes, as well as therapist and client characteristics predicting positive outcomes.

(2001). Practice guideline for the treatment of patients with borderline personality disorder. American Journal of Psychiatry, 158, 1-52. doi:10.1176/appi. books.9780890423363.54853Crossref, Google Scholar

(2004).Mentalization-based treatment of BPD. Journal of Personality Disorders, 18, 36-51. doi:10.1521/pedi.18.1.36.32772Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

(1961). An inventory for measuring depression. Archives of General Psychiatry, 41, 561-571. doi:10.1001/archpsyc. 1961.01710120031004Crossref, Google Scholar

(2002). STEPPS: A cognitive-behavioral systems-based group treatment for outpatients with borderline personality disorder – A preliminary report. Comprehensive Psychiatry, 43, 301-310. doi:10.1053/comp.2002.33497Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

, (2008). Systems training for emotional predictability and problem solving (STEPPS) for outpatients with borderline personality disorder: A randomized controlled trial and 1-year follow-up. American Journal of Psychiatry, 165, 468-478. doi:10.1176/appi.ajp.2007.07071079Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

(2012). Three cases of dissociative identity disorder and co-occurring borderline personality disorder treated with dynamic deconstructive psychotherapy. American Journal of Psychotherapy, 66, 165-180.Link, Google Scholar

(2007). Evaluating three treatments for borderline personality disorder: A multi-wave study. American Journal of Psychiatry, 164, 1-8. doi:10.1176/appi.ajp.164.6.922Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

(1992). A power primer. Psychology Bulletin, 1, 155-159. doi:10.1037/0033-2909.112.1.155Crossref, Google Scholar

(2007).Effectiveness of dialectical behavior therapy in a community mental health center. Cognitive and Behavioral Practice, 14, 406-414. doi:10:1016/j.cbpra.2006.04.023Crossref, Google Scholar

(1999). Lifetime Parasuicide Count (LPC). Seattle, WA: University of Washington.Google Scholar

(2012). A manual-based treatment approach for training psychiatry residents in psychodynamic psychotherapy. Journal of the American Psychoanalytic Association, 60, 591-598. doi:10.1177/0003065112450148Google Scholar

(1997). Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis II Personality Disorders (SCID II, Version 2.0). Washington, D.C.: American Psychiatric Press, Inc.Google Scholar

, (1995). Individual assessment profile (IAP): Standardizing the assessment of substance abusers. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment, 12, 213-221. doi:10.1016/0740-5472(95)00023-XCrossref, Medline, Google Scholar

(2006). Outpatient psychotherapy for borderline personality disorder: Randomized trial of schema-focused therapy vs transference-focused psychotherapy. Archives of General Psychiatry, 63, 649-658. doi:10.1001/archpsyc.63.6.649Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

(2007). Reliability and validity of the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale and the Beck Depression Inventory (Full and FastScreenscales) in detecting depression in persons with hepatitis C. Journal of Affective Disorders, 100, 265-269. doi:10.1016/j.jad.2006.10.020Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

(2009). Preliminary relationships between adherence and outcome in dynamic deconstructive psychotherapy. Psychotherapy: Theory, Research, Practice, Training, 46, 480-485. doi:10.1037/a0017947Crossref, Google Scholar

(2010). Relationships between techniques and outcomes for borderline personality disorder. American Journal of Psychotherapy, 64, 359-371.Link, Google Scholar

(2005). The deconstructive experience. American Journal of Psychotherapy, 59, 295-305.Link, Google Scholar

(2007). Borderline attributions. American Journal of Psychotherapy, 61, 131-147.Link, Google Scholar

(2008). A controlled trial of psychodynamic psychotherapy for co-occurring borderline personality disorder and alcohol use disorder. Psychotherapy: Theory, Research, Practice, Training, 45, 28-41. doi:10.1037/0033-3204.45.1.28Crossref, Google Scholar

(2010). Dynamic deconstructive psychotherapy versus optimized community care for borderline personality disorder co-occurring with alcohol use disorders: 30-month follow-up. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease, 198, 292-298. doi:10.1097/NMD.0b013e3181d6172dCrossref, Medline, Google Scholar

(2008). A manual-based psychodynamic therapy for treatment-resistant borderline personality disorder. Psychotherapy: Theory, Research, Practice, Training, 45, 15-27. doi:10.1037/0033-3204.45.1.15Crossref, Google Scholar

(2007). Use of dialectical behavior therapy skills training for borderline personality disorder in a naturalistic setting. Psychotherapy Research, 17, 362-370. doi:10.1080/10503300600830710Crossref, Google Scholar

, (2001). Efficacy of dialectical behavior therapy in women veterans with borderline personality disorder. BehavTher, 32, 371-390. doi:10.1016/S0005-7894(01)80009-5Google Scholar

(2004). Randomized controlled versus naturalistic studies: A new research agenda. Bulletin of the Menninger Clinic, 68, 137-151. doi:10.1521/bumc.68.2.137.35952Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

. (2010). Pharmacotherapy for borderline personality disorder: Cochrane systematic review of randomized trials. British Journal of Psychiatry, 196, 4-12. doi:10.1192/bjp.bp.108.062984Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

(1993). Cognitive Behavioral Treatment of Borderline Personality Disorder. New York: Guilford.Google Scholar

(1991). Cognitive-behavioral treatment of chronically parasuicidal borderline patients. Archives of General Psychiatry, 48, 1060-1064. doi:10.1001/archpsyc.1991.01810360024003Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

, (2006). Two-year randomized controlled trial and follow-up of dialectical behavior therapy vs therapy by experts for suicidal behaviors and borderline personality disorder. Archives of General Psychiatry, 63, 757-766. doi:10.1001/archpsyc.63.7.757Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

, (1999). The researcher’s own therapy allegiances: A “wild card” in comparisons of treatment efficacy. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice, 6, 95-106. doi:10.1093/clipsy.6.1.95Crossref, Google Scholar

(2010). Factor structure, internal consistency and construct validity of the Sheehan Disability Scale in a Spanish primary care sample. Journal of Evaluation in Clinical Practice, 16, 895-901. Doi:10.1111/j.1365-2753.2009.01211.xCrossref, Medline, Google Scholar

(2012). Dialectical behavior therapy compared with general psychiatric management for borderline personality disorder: Clinical outcomes and functioning over a 2-year follow-up. American Journal of Psychiatry, 169, 650-661. doi:10.1176/appi.ajp.2012.11091416Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

(1996). Beyond the Tower of Babel: a nomenclature for suicidology. Suicide and Life-Threatening Behavior, 26, 237-252. doi:10.1111/j.1943-278X.1996.tb00609.xMedline, Google Scholar

(2008). Efficacy of the third wave of behavioral therapies: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 46, 296-321. doi:10.1016/j.brat.2007.12.005Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

(2009). Reliability and validity of the Borderline Evaluation of Severity Over Time (BEST): A self-rated scale to measure severity and change in persons with borderline personality disorder. Journal of Personality Disorders, 23, 281-293. doi:10.1521/pedi.2009.23.3.281Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

(2010). Response and remission criteria in major depression: A validation of current practice. Journal of Psychiatric Research, 44, 1063-1068. doi:10.1016/j.jpsychires.2010.03.006Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

(1996). The measurement of disability. International Clinical Psychopharmacology, 11(Suppl 3), 89–95. doi:10.1097/00004850-199606003-00015Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

(2003). Are samples in randomized controlled trials of psychotherapy representative of community outpatients? A new methodology and initial findings. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 71, 963-972. doi:10.1037/0022-006X.71.6.963Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

(2012). Premature discontinuation in adult psychotherapy: A meta-analysis. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 80, 547-559. doi:10.1037/a0028226Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

(2002). Dialectical behavior therapy of borderline patients with and without substance use problems: Implementation and long-term effects. Addictive Behaviors, 27, 911-923. doi:10.1016/S0306-4603(02)00293-9Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

(2003). Dialectical behaviour therapy for women with borderline personality disorder: 12-month,randomised clinical trial in The Netherlands. British Journal of Psychiatry, 182, 135-140. doi:10.1192/bjp.02.184Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

(2012). Attainment and stability of sustained symptomatic remission and recovery among patients with borderline personality disorder and Axis II comparison subjects: A 16-year prospective follow-up study. American Journal of Psychiatry, 169, 476-483. doi:10.1176/appi.ajp.2011.11101550Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

(2001). The Psychiatric Diagnostic Screening Questionnaire: Development, reliability, and validity. Comprehensive Psychiatry, 42, 175-189. doi:10.1053/comp.2001.23126Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar