Intensive Individual and Group Cognitive Behavioural Therapy for Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder

Abstract

Whilst there is good evidence to show intensive individual therapy can be effective for obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD), this treatment can be challenging to deliver for therapists in the National Health Service (NHS). We report on a novel means of delivering intensive cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT) by combining it with group work, which allowed therapists to offer each other mutual support and permitted patients to gain the interpersonal benefits of working with others. This case study describes the combined intensive individual and group CBT programme for a 46-year-old woman with OCD. This treatment took place within a community mental health team within outer London. Following treatment, the client showed significant improvements in symptoms. This creative method for treating OCD as part of routine clinical practice may be beneficial for therapists to feel supported, for reduction in clinicians’ time in treatment, and for clients to benefit from a group experience.

Introduction

Obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD) is a chronic and disabling condition that affects approximately 2% to 3% of the population and is associated with high levels of comorbidity, elevated suicidal acts, and social and occupational impairment (Salkovskis, 2007). Early behavioural theories formulated OCD as avoidance conditioning (Dollard & Miller, 1950). That is, certain stimuli (e.g. objects, thoughts) trigger an anxiety response after being experienced with an event that causes distress. Engaging in compulsive behaviours reduces this anxiety and thus become reinforcing (Turner, Hersen, Bellack, & Wells, 1978). The cognitive model of OCD, developed by Salkovskis (1985), proposes that obsessional thinking starts from normal intrusive cognitions. It is based on the well-established finding that unwanted intrusive thoughts, images, and urges are experienced by most people and have similar contents to clinical obsessions (Abramowitz, Taylor, & McKay, 2009). The difference between normal and obsessional intrusive cognitions lies in how their occurrence and content are interpreted (Salkovskis, 1999). In Salkovskis’ model, intrusions are interpreted as an indication that the individual may be responsible for harm or its prevention. This interpretation leads to anxiety and neutralising behaviours (e.g. compulsions, seeking reassurance, avoidance) to reduce distress (Morrison & Westbrook, 2006). However, neutralising prevents the individual from learning their appraisals about responsibility are unrealistic (Abramowitz et al., 2009), so they continue to try to control their obsessions; hence the obsessive-compulsive problem is maintained.

In terms of effective treatment, the National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE) guideline for OCD (2006) recommends cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT), including exposure and response prevention (ERP), as a first line intervention. The efficacy of CBT and ERP for OCD has been well established (Abramowitz, Foa, & Franklin, 2003; Anderson & Rees, 2007; Department of Health, 2001; NICE, 2006; Storch et al., 2008), and improving access to psychological therapy is currently a priority for the Department of Health (“Organising and Delivering Psychological Therapies,” 2004). Attempts to improve CBT access for OCD clients have focused on changing the mode of delivery to be more flexible or require reduced clinician time. Two such approaches include (1) offering treatment in a group, or (2) delivering individual psychological therapy intensively so that daily therapy sessions are provided during a number of weeks (Storch et al., 2008).

Group CBT, including ERP, has been shown to be an effective treatment for OCD, (Hougaard, 2009) and when compared to individual CBT, it produces similar outcomes (Anderson & Rees, 2007). It may provide a more cost-effective way for clients to access treatment, as it requires a reduced amount of clinician input relative to individual psychological therapy. In addition, patients frequently benefit from nonspecific factors associated with group work, such as normalisation, support, and encouragement from the group (Anderson & Rees, 2007). However, it is hard to carry out behavioural experiments and individually tailored ERP with therapist support within a group, which may leave the needs of some clients unmet.

There are positive results relating individual CBT and ERP intensively delivered. Abramowitz et al. (2003) compared a twice-weekly ERP programme with an intensive version. Results indicated both programmes were effective but greater improvements were seen in the intensive group, although these did not remain at three month follow up. More recently, Storch et al. (2008) showed intensive CBT for OCD to be as effective as weekly CBT, with treatment gains being maintained three months later. An intensive approach may be advantageous for treatment-resistant patients (Oldfield, Salkovskis, & Taylor, 2011), where appropriate treatment is not locally available, or where a more rapid reduction in symptoms is needed due to significant functional impairments (Storch et al., 2008).

One example of an effective intensive CBT programme for OCD within the UK, has been investigated at The Centre for Anxiety Disorders and Trauma (South London and Maudsley National Health Service (NHS) Foundation Trust; Oldfield et al., 2011). Their innovative treatment consists of 12 to 18 hours of therapy delivered in five days, during a ten-day period to allow time for behavioural experiments and other homework between sessions. Sessions are offered on a 2:1 basis so that each client works with two therapists at any one time. Three one-hour follow-up sessions are offered at one, two, and three months after the end of treatment. In a research study comparing this intensive programme to weekly CBT, Oldfield et al. (2011) found both conditions to be equally effective in significantly reducing OCD symptoms.

Offering individual psychological therapy delivered concurrently by two therapists may be ideal but often is not cost effective in NHS settings. An alternative approach may be to deliver the therapy on a 1:1 basis. However, for a single therapist, delivering up to 18 hours of individual therapy with a single client over a short period may be challenging. For example, the therapist may have little time between sessions to discuss the case with colleagues, to refer to the cognitive model when necessary, to plan sessions, and to develop ideas for behavioural experiments. One possible means of offering additional support for therapists is to augment intensive individual therapy with group work. This may both provide additional benefits to clients in terms of a group experience and increase time-efficiency and cost-effectiveness in delivering therapy. Combining individual CBT with group work is not entirely novel and has been implemented successfully for hypochondriasis (Sorensen, Birket-Smith, Wattar, Buemann, & Salkovskis, 2011) and OCD (“The House of Obsessive Compulsives,” Channel 4, 2005). However, the use of this approach has not been formally evaluated in OCD. In our service, a psychological therapies team (PTT) within a secondary care community mental health team in outer London, a combined approach like this was developed so that a number of therapists (up to six) provided individual intensive CBT for OCD during the same fortnight period. Group sessions were offered to all clients twice during this time and once as a followup. This approach provided a number of advantages:

| (1) | It retained the benefits of individual therapy in facilitating the use of idiosyncratic formulation, personally tailored treatment, and individual support for behavioural experiments, whilst still allowing clients to gain the support of other clients and therapists within the group setting; | ||||

| (2) | clinician time was reduced as some of the therapy sessions were carried out in groups in which not all clinicians were involved, and | ||||

| (3) | as therapists had met most of the clients during one of the groups, therapists with a range of skill and experience level were able to support and supervise each other in planning individual sessions with client. | ||||

In this way, we were able to implement the NICE guideline (2006), recommending intensive treatment (more than ten hours of therapy) for OCD clients. Group CBT for OCD has been criticised for under treating participants as insufficient time is spent on identifying and challenging individual intrusive thoughts (Anderson & Rees, 2007). The current intervention was, therefore, advantageous as it included individual as well as group sessions. This case study describes the treatment of a client who took part in this intensive individual CBT programme augmented with groups, and we describe some of the strengths and considerations of such an approach as well as evaluating its success.

Case Summary

Participant Selection and Reason for Referral

The case study aims to describe an individualised treatment programme with the addition of group work and so includes outcomes only for this case rather than the whole group. Each person had an individual formulation and treatment plan and the way the individual sessions were delivered in relation to the groups was different for each client. In this way, each person went through a process which was specific to them rather than general to the group. Therefore, we wanted to describe in detail the complete therapeutic process for an individual as an illustration of the method.

Linda (not her real name) was a 46-year-old Caucasian woman who was referred by her general practitioner (GP) to the PTT as per usual procedure. She was assessed by a member of the PTT and considered suitable to be offered psychological therapy within a secondary mental health service as she met the criteria of experiencing a severe and enduring mental health problem that was significantly impacting on her functioning and that had not responded to primary care interventions including anti-depressant medication and brief counselling (fewer than six sessions). She was, therefore, representative of patients generally offered psychological treatment within the PTT and was put on the waiting list for therapy for approximately six months. When the current intervention became available, clients from the waiting list were contacted to offer them therapy, based on how long they had been waiting to be seen. Clients accepting treatment were allocated to five available therapists according to case complexity and therapist expertise.

She was treated by RT (first author), who was undertaking her final year placement on her doctoral in clinical psychology training within the team, and this client presented with moderately severe difficulties relative to other group members. One of the requirements of the doctoral training is to write up individual case studies of particular clinical interest, and this client was selected as an example of someone who received a novel treatment approach.

Linda’s GP reported that she was suffering with persistent and overwhelming anxiety that had not improved with medication or brief CBT. She worked as a teaching assistant and was married with two children. She described her husband as immensely supportive.

Presenting Problem

At psychological assessment Linda reported suffering with anxiety for five years. It started when her mother was in poor health and her children were starting secondary school. She currently experienced intrusive thoughts regarding threat and harm coming to friends, family, strangers she would pass in the street, and even inanimate objects. Linda feared her house would be broken into and her belongings damaged or stolen. She often worried her house would catch fire through carelessness and burn down. She frequently double checked to make sure the doors were locked and electrical cords were unplugged from sockets prior to leaving the house, which she reported taking 20 to 30 minutes because of her rituals. She said she no longer drove to ensure she did not have an accident and injure anyone, including animals. She described this causing difficulty for her children, as she was unable to drive and collect them from school or from friends’ houses. Linda recognised her thoughts and fears were irrational and attempted to rationalise these thoughts, with variable success. Her symptoms caused constant anxiety, and she described problems with everyday tasks. Linda found it difficult to go to work as this required a short walk and she feared what might happen to strangers along the way if she looked at them. To avoid seeing anyone, distraction and looking at the floor formed part of her coping strategies. She admitted to missing work some days as she was unable to leave the house. On these occasions she coped with her anxiety by staying in bed. She reported being unable to engage in activities she enjoyed doing alone, such as shopping, and always had to ask a family member to accompany her for reassurance. She also felt her difficulties were impacting on her relationship with her children. Often she found herself unable to spend time with them outside the house and reported missing out on family outings.

Formulation

Linda’s formulation is presented in Figure 1. She was suffering with OCD and frequently had intrusive thoughts that something bad was going to happen. For example, before leaving home she had thoughts her house would burn down and that if she went out alone a stranger would get run over, fall, or injure themselves in some way. Her intrusive thoughts led her to experience anxiety and she perceived an overinflated sense of responsibility for harm or its prevention. Linda’s perception of harm also included mental suffering (Veale, 2007) as she feared her anxiety would last forever. She acted in a manner to prevent or reduce anxiety and perceived harm. She checked items before leaving the house, prevented herself from looking at others whilst outside, avoided doing things alone, and sought reassurance from others. However, these compulsions and avoidance behaviours never allowed her to see that bad things happened infrequently and that when they did occur they were not her responsibility. Linda reported her mother ‘suffered with her nerves’ and there was a sense of vicarious learning. After the death of her father Linda worked closely with her mother to maintain their home and look after her siblings. She was given responsibilities from a young age and was more exposed to her mother’s anxiety. She appeared to have developed beliefs that it was her responsibility to care for and protect others. The start of her OCD coincided with a time when she felt responsible for protecting her mother and children.

Figure 1. LINDA’s FORMULATION (THE VICIOUS FLOWER COGNITIVE MODEL OF OCD, SALKOVSKIS, FORRESTER, & RICHARDS, 1998)

Method

Design and Procedure

This single case study used a within subject AB design with follow-up. Linda completed self-report outcome measures at baseline (one month before the start of intervention), pre-intervention (the day before the start of intervention), weekly during intervention, post-intervention (the day after the end of treatment), and during follow-up sessions. She also completed a client satisfaction questionnaire at the end of treatment.

Outcome Measures

The Obsessive-Compulsive Inventory-Revised ([OCI-R] Foa et al., 2002) is a psychometrically reliable and valid 18-item questionnaire that measures distress associated with the symptoms of OCD. Items are rated on a five-point scale and form six subscales based on symptom categories commonly found in OCD. A total symptom score is calculated (range 0 to 72) and a clinical cutoff score of 21 or above indicative of the likely presence of OCD (Foa et al., 2002).

The Beck Depression Inventory–2nd Edition ([BDI-II] Beck, Steer, & Brown, 1996) is a 21-item self-report questionnaire that assesses cognitive, behavioural, and somatic symptoms of depression during the previous two weeks. Items are scored on a 0-to-3 scale giving a total score out of 63 being the most depressed. Scores of 0 to 7 are considered within the normal range, 8 to 13 within the minimal depression range, 14 to 19 within the mild range, 20 to 28 within the moderate range, and 29 to 63 within the severe range of depression. The BDI-II has been found to have good reliability and validity (Beck et al., 1996).

The Beck Anxiety Inventory ([BAI] Beck, Epstein, Brown, & Steer, 1988) is a 21-item self-report questionnaire that measures the severity of an individual’s anxiety. Anxiety symptoms are scored on a 0-to-3 scale, with a total score of up to 63 points. Scores of 0 to 7 indicate minimal anxiety, 8 to 15 points indicate mild anxiety, scores between 16 to 25 points indicate moderate anxiety, and between 26 to 63 points indicate severe anxiety. The BAI has been shown to have high internal consistency and test-retest reliability and good concurrent and discriminant validity (Beck et al., 1988).

The Work and Social Adjustment Scale ([WSAS] Mundt, Marks, Shear, & Greist, 2002) is a self-report questionnaire assessing an individual’s functional impairment. Participants rate their impairment on a 0 to 8 scale for five items assessing functioning in the areas of work, home management, leisure activities, and relationships. A total symptom score is calculated (range 0 to 40), and a clinical cutoff score of 10 or above associated with significant functional impairment. The WSAS has been shown to be a reliable and valid measure (Mundt et al., 2002).

The Client Satisfaction Questionnaire–8 ([CSQ-8] Nguyen, Attkisson, & Stegner, 1983) consists of eight items that give a global measure of a patient’s service satisfaction. Items are scored on a 4-point Likert scale giving a total score out of 32. The CSQ-8 is a component scale of the larger Service Evaluation Questionnaire ([SEQ] Nguyen et al., 1983), which has been demonstrated to have excellent internal consistency and solid psychometric properties. Nguyen et al. (1983) provide norms against which patient satisfaction can be compared. High scores correspond to high levels of satisfaction.

Results

Course of Therapy and Assessment of Progress

Linda completed three group sessions run by two therapists. The first session was carried out over one full day (five hours), and remaining sessions lasted two hours each. Linda completed eight individual sessions, which took place twice weekly between group sessions and after the group intervention had ended. Individual sessions lasted 60-to-90 minutes. In total Linda received 18 hours of therapy over four weeks.

Five clients attended the group. The format was fairly structured and aimed to offer an introduction to OCD treatment and to the CBT model. Clients were encouraged to contribute if they chose to. The first session started with normalising intrusive thoughts. Clients were presented with a list of intrusive thoughts taken from a community sample and were asked to discuss the similarities of intrusive thoughts between those with and without OCD (Veale, 2007). Clients were encouraged to see their intrusions were not the problem but rather the problem was the meaning they attached to the intrusions that caused of their difficulties.

Salkovskis’ (1985) cognitive model was illustrated using the “vicious flower”1 and examples of the group’s own intrusions. Clients were encouraged to question whether their obsessional behaviour was a helpful way of dealing with intrusions, or whether this behavior, in fact, was part of the problem and its maintenance (Salkovskis, 1999). They then considered a less threatening view of their difficulty, seeing it instead as a problem of excessive worry (Salkovskis, 1999). The implications of holding this alternative belief were then considered to allow clients to see what they needed to change. Towards the end of the day clients met with their individual therapists and developed their own formulations based on the cognitive model.

Linda’s goals were to be able to understand her intrusive thoughts as just thoughts and to realize she did not have to react to them with feelings of responsibility. She described wanting to get back to “living” again because her thoughts had prevented her from doing some activities she enjoyed. Linda wanted to work on her avoidance and not on her “checking” as she felt this was already improving. A less threatening interpretation of Linda’s intrusive thought, “something bad was going to happen,” was discussed in the group. She saw she was someone who was naturally concerned about bad things happening and she worried she was responsible for preventing harm. She also remembered times when she had been unable to avoid situations that worried her, such as when her children went on school trips. On these occasions her worries had not come to pass, and Linda realised her avoidance behaviour prevented her from testing her worries against the reality of the situation.

Individual work followed the formulation developed in the group, and it consisted primarily of conducting a series of behavioural experiments. For example, Linda was encouraged to open her curtains and actively look for danger. She practised walking outdoors with her head up to see if anything bad was happening. She subsequently learnt that thought her anxiety increased when she took on new challenges, it always came down, and the more she exposed herself to her anxiety, the quicker it subsided. She also learnt she did not need to avoid situations to prevent bad things from happening. The availability of longer sessions allowed Linda to carry out experiments testing her belief that something bad was going to happen to someone she encountered in a shopping centre or whilst she was driving. Pie charts were used to challenge responsibility appraisals (Salkovskis, 1999), and Linda came up with her own reality-testing technique that she named the “silent survey.” When she felt someone was in danger she would look around to see how others were responding. Frequently, she observed others had not even noticed the situation about which she was concerned. This enabled her to establish what other people did when they were in the same situation as she might be and it gave her insight into what “normal” responsibility for that situation may be. This shifted her belief that a “real” danger was imminent and that it she was responsible for preventing harm. Linda also found cognitively distancing herself from her thoughts helpful (Veale, 2007).

The second group session consisted of thinking about the pros and cons of change, and the third group session focused on relapse prevention. Clients also reported their progress, and any difficulties or questions were discussed. The group gave feedback on how they had found the intensive programme.

Follow Up

Linda attended individual follow-up sessions one and two months after therapy. At one month she described an increase in anxiety and she had started to avoid situations. Linda’s relapse prevention plan was reviewed and her current circumstances reframed as a learning experience. At two-month follow up Linda reported things had improved and her anxiety had reduced. She felt she had the tools to continue working on her OCD and was discharged.

Treatment Outcome

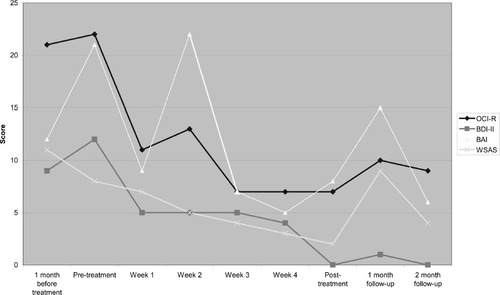

Linda’s outcome scores are presented in Table 1 and in Figure 2. One month before the start of treatment she reported mild anxiety and symptoms of OCD. These were significantly impacting on her functioning, although there were no symptoms suggestive of depression. A day before starting treatment Linda was experiencing moderate anxiety and symptoms of OCD in the clinical range. Whilst her OCI-R score was just within the clinical range, she later admitted to underreporting her symptoms as she was unsure about pursuing psychological treatment. Furthermore, since she had been on the waiting list for some time; it is possible that she had experienced some improvement during this time. Nevertheless, she reported her difficulties having a significant impact on her everyday functioning.

| Outcome Measure | ||||

| Time | OCI-R | BDI-II | BAI | WSAS |

| 1 month before treatment | 21 | 9 | 12 | 11* |

| Pre-treatment | 22* | 12 | 21 | 8 |

| Week 1 | 11 | 5 | 9 | 7 |

| Week 2 | 13 | 5 | 22 | 5 |

| Week 3 | 7 | 5 | 7 | 4 |

| Week 4 | 7 | 4 | 5 | 3 |

| Post-treatment | 7 | 0 | 8 | 2 |

| 1 month follow up | 10 | 1 | 15 | 9 |

| 2 month follow up | 9 | 0 | 6 | 4 |

Table 1. LINDA’s OUTCOME MEASURE SCORES

Figure 2. GRAPHICAL DISPLAY OF LINDA’s OUTCOME MEASURE SCORES

Over the course of therapy Linda’s scores on the OCI-R, BAI, and WSAS, moved from the clinical range to the normal range, indicating significant improvements in her symptoms of OCD and anxiety as well as her functioning. Her anxiety fluctuated over the course of treatment as she challenged her avoidance. At one month-follow up there was an increase in symptoms on all measures but these improved at two month follow-up returning to the normal range.

Linda spoke favorably about the treatment approach, and reported a high level of satisfaction with the service she received as assessed by the CSQ-8. She described the group sessions as reassuring because she came to know she was not alone in the difficulties she faced. She also reported learning useful ideas from other clients. She admitted to being concerned initially about an intensive approach. She was worried her anxiety would be too much to face, but she also hoped intensive therapy would improve her symptoms quickly so that everyday tasks, such as going to work would be more manageable. At the end of therapy Linda reported she was pleased to have been offered an intensive treatment. Her symptoms reduced rapidly, and she noticed improvements in functioning. She found regular contact with her therapist helpful in addressing any concerns promptly, and she described the intensive approach as giving her strength to tackle her OCD. She felt longer breaks between sessions would have allowed her anxiety to become overwhelming, and it would have been more difficult to achieve improvements.

Therapist’s Experience of Treatment

Working intensively with Linda was challenging at times. She appeared somewhat ashamed of her difficulties, and she very anxious to refrain from performing her compulsive behaviours. Attending group treatment was particularly advantageous in normalising Linda’s problems. Hearing others’ successes and difficulties also appeared to motivate Linda to engage fully in treatment, and frequent individual sessions gave her a sense of momentum in challenging her compulsions and avoidance behaviours. However, meeting regularly was, at times, difficult for the therapist. Sessions had to be planned quickly and supervision sought where possible. The addition of group work reduced pressure on the therapist to be creative with behavioural experiments because ideas were shared within the group and support was received from other therapists. Moreover, a number of the tasks were conducted in the group (e.g. socialising clients to the cognitive model), reducing the demands of therapy within individual sessions, which could be more focused on ERP and behavioural experiments. The group also provided an ideal opportunity for the therapist to receive training and modelling of skills from other more experienced colleagues.

Discussion

This case study demonstrates CBT can be effective for reducing OCD symptoms when delivered in an intensive individual and group format as part of routine clinical practice. It described Linda, a 46-year-old woman with OCD, who completed intensive individual CBT supplemented with group sessions. She experienced clinically significant improvements in all symptoms, moving from the clinical range to the normal range as assessed by self-report outcome measures. These improvements were maintained at two-month follow up. This is consistent with research evidence that suggests that both group CBT and intensive individual CBT can be effective in reducing the symptoms of OCD (Anderson & Rees, 2007; Oldfield et al., 2011).

Working intensively can be challenging. There can be little time for planning sessions or seeking supervision (particularly given that intensive work can provoke a high level of emotional intensity), and it can be difficult to maintain creativity when helping patients to design behavioural experiments. Therefore, the addition of group work to intensive treatment has the potential to improve access to psychological therapy by reducing the amount of clinician time required for a course of treatment, and ensures therapists are well supported in intensive individual work. A number of the tasks of therapy were conducted in the group, and although these might be followed-up within individual sessions, the demands of therapy within individual sessions were somewhat reduced. Group CBT for OCD has been criticised for undertreating participants as insufficient time is spent on identifying and challenging individual intrusive thoughts (Anderson & Rees, 2007). The current intervention was, therefore, advantageous as it included individual as well as group sessions. It also appeared to be time-efficient. Linda received 18 hours of treatment. However, group sessions consisted of five clients each sharing nine hours of therapy provided by two therapists. Therefore, Linda received less than 18 hours of direct therapy and, in fact, received 10 hours and 48 minutes in total.

We were looking for creative ways to address our waiting list and heavy caseloads. Therapists were interested in new ways of working and reported feeling supported by one another when implementing this intensive intervention. They felt it was a break from their everyday routine and said working intensively was rejuvenating in some way. In general, therapists managed to carry out the intensive work by taking one or two weeks away from most of their regular weekly therapy sessions, as one might do for a period of annual leave or training. In addition to the face-to-face contact with patients, therapists met several times throughout the week for peer supervision. Trainees and less-experienced qualified clinicians in some cases had additional individual supervision. The groups allowed therapists to get to know all clients in treatment so they could offer supervision and encouragement to fellow therapists.

Whilst intensive CBT/ERP has generally been recommended for people who are treatment resistant or who need a more rapid reduction in symptoms due to significant functional impairments, there are a number of other advantages to this approach. In this case, working intensively with a therapist appeared to make it easier for this client to engage with ERP, and it allowed the chaining of progressively more challenging behavioural experiments as the client knew her efforts would be matched with equal support (Oldfield et al., 2011). Indeed, other clients in the intensive programme said seeing their therapist frequently allowed them to gain momentum in challenging their compulsions and avoidance behaviours, which motivated them to continue with treatment.

This case study evaluated a combined intensive individual and group intervention for OCD. In this case the treatment was effective, feasible, and acceptable to the client. However, limitations should be noted. Firstly, data from other group members are not reported here. Therefore, it is difficult to draw conclusions relating to the group aspect of treatment. Nevertheless, this study aimed to describe an individualised treatment programme. Secondly, Linda admitted to underreporting her symptoms prior to treatment, which makes the use of a self-report scale unreliable. A clinician rating measure, such as the Yale Brown Obsessive Compulsive Scale (Goodman et al., 1989) or an observational measure, may have provided a more accurate picture. Thirdly, our treatment protocol required therapists’ taking time away from most of their regular weekly therapy sessions. This was often considered to offer a welcome break from their everyday routine. Working closely with other colleagues also felt rejuvenating and provided an ideal opportunity to offer training to less experienced colleagues. The sustainability of such an approach in a routine clinical setting may be difficult. It was manageable in our team, in which the referral rate of OCD cases necessitated groups taking place about every six months. Lastly, this case study is the first stage in evaluating such a combined intensive individual and group intervention. It used an AB design, which did not allow for the control of extraneous variables. We, therefore, cannot draw casual links between our treatment approach and Linda’s positive change. Larger pilot studies are now needed to see if these findings are generalisable and whether such benefits could occur for those with more complex and severe presentations.

(2003). Exposure and ritual prevention for obsessive-compulsive disorder: effects of intensive versus twice-weekly sessions. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 71(2), 394–398.Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

(2009). Obsessive-compulsive disorder. Lancet, 374, 491–499.Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

(2007). Group versus individual cognitive-behavioural treatment for obsessive-compulsive disorder: a controlled trial. Behaviour Research, 45, 123–137.Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

(1988). An inventory for measuring clinical anxiety: psychometric properties. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 56(6), 893–897.Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

(1996). Manual for the Beck Depression Inventory-II. San Antonio, TX: Psychological Corporation.Google Scholar

. (2001). Treatment Choice in Psychological Therapies and Counselling. Evidence Based Clinical Practice Guideline Brief Version. London: Department of Health.Google Scholar

. (2004). Organising and Delivering Psychological Therapies. London: Department of Health.Google Scholar

(1950). Personality and psychotherapy: An analysis in terms of learning, thinking and culture. New York: McGraw-Hill.Google Scholar

(2002). The obsessive-compulsive inventory: development and validation of a short version. Psychological Assessment, 14(4), 485–496.Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

The Yale-Brown Obsessive-Compulsive Scale, I: development, use, and reliability. Archives of General Psychiatry, 46, 1006–1011.Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

(2009). Group cognitive behavioural therapy for obsessive-compulsive disorder: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica, 119, 98–106.Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

(2006). Obsessive-compulsive disorder. In J. Bennett-LevyG. ButlerM. FennellA. HackmanM. MuellerD. Westbrook (Eds.), Oxford Guide to Behavioural Experiments in Cognitive Therapy (pp. 101–118). Oxford: Oxford University Press.Google Scholar

(2002). The work and social adjustment scale: a simple measure of impairment in functioning. British Journal of Psychiatry, 180, 461–464.Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

. (2006). Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder: Core Interventions in the Treatment of Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder and Body Dysmorphic Disorder. London: NICE.Google Scholar

(1983). Assessment of patient satisfaction: development and refinement of a service evaluation questionnaire. Evaluation and Program Planning, 6, 299–314.Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

(2011). Time-intensive cognitive behavioural therapy for obsessive-compulsive disorder: a case series and matched comparison group. British Journal of Clinical Psychology, 50, 7–18.Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

(1985). Obsessional-compulsive problems: a cognitive-behavioural analysis. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 23, 571–583.Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

(1999). Understanding and treating obsessive-compulsive disorder. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 37, S29–S52.Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

(2007). Obsessive-compulsive disorder is uncommon but associated with high levels of comorbid neuroses, impaired function and increased suicidal acts in people in the UK. Evidence Based Mental Health, 10, 93.Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

(1998). Cognitive-behavioural approach to understanding obsessional thinking. The British Journal of Psychiatry, 35, S53–S63.Crossref, Google Scholar

(2011). A randomized clinical trial of cognitive behavioural therapy versus short-term psychodynamic psychotherapy versus no intervention for patients with hypochondriasis. Psychological Medicine, 41, 431–441.Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

(2008). Cognitive-behavioral therapy for obsessive-compulsive disorder: a non-randomized comparison of intensive and weekly approaches. Journal of Anxiety Disorders, 22, 1146–1158.Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

(1978). Behavioral treatment of obsessive-compulsive neurosis. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 17, 95–106.Crossref, Google Scholar

(2007). Cognitive-behavioural therapy for obsessive-compulsive disorder. Advances in Psychiatric Treatment, 13, 438–446.Crossref, Google Scholar