Active Change in Psychodynamic Therapy: Moments of High Receptiveness

Abstract

This article presents the concept of “moments of high receptiveness” (MoHR or “Momentos de Alta Receptividad”), which is derived from the concept of “experiential coupling” (“Acoplamiento de Experiencias”) proposed by Bleichmar (2001). Experiential coupling recently received empirical support by the work of Schiller and colleagues (2010). We will also show the conceptual placing of moments of high receptiveness with respect to the developments of Stern and colleagues (Stern and et al., 1998; Stern, 2004). In order to achieve both objectives, we focus on various clinical vignettes stressing the differences in repercussions of the technique. We describe use of stimuli for active evocation, explain how to identify moments of high receptiveness, and review ways to take advantage of these moments. Lastly, to minimize the risk of iatrogenic symptoms, we examine the role of therapists and some features of the therapeutic process when using this technique.

Introduction

Efficacy of Psychodynamic Therapy

Psychodynamic therapy is gradually overcoming the traditional criticisms of being both a technique in which there is little research interest and a modality marked by a lack of dialogue with other branches of therapeutic practice.

A study published by the American Psychological Association (Shedler, 2010) that reviewed eight meta-analyses comprising 160 studies of psychodynamic therapy, plus nine meta-analyses of other psychological treatments and antidepressant medications, concluded that: “Empirical evidence supports the efficacy of psychodynamic therapy. Effect sizes for psychodynamic therapy are as large as those reported for other therapies that have been actively promoted as “empirically supported” and “evidence based” (p. 98).

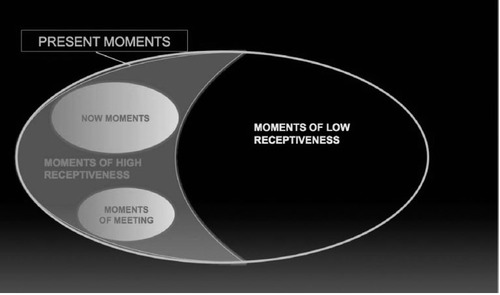

Partially responsible for the efficacy of psychodynamic therapy is the remarkable impetus of theoretical developments in therapeutic change during the last 15 years. The developments of Stern and his colleagues (members of the Boston Change Process Study Group, 2010) occupy a prominent place in this field. They applied a developmental perspective to clinical material to show the noninterpretative mechanisms of change in the therapeutic relationship (“the something more” in Stern’s words) (Stern et al., 1998). Stern further elaborated on these ideas, introducing the concept of “present moment” (Stern, 2004), which encompasses the concepts of both “now moments” and “moments of meeting.” Stern proposed moving from explicit knowledge (the therapist giving meaning to patients’ narratives) to the implicit knowing that occurs in the present moment as an embodied experience within which both therapist and patient live.

In addition to addressing the research criticism, we offer the following to highlight the mutually fruitful dialogue between psychodynamic therapy and neuroscience.

| • | Westen (1999) and Kandel (2007), among others, support that advances in neuroscience have confirmed many of the basic elements of psychoanalytic theory (whilst obviously also dismissing others). | ||||

| • | Advances in neuroscience have brought about changes in the development of psychoanalytic theory and technique. For example, discoveries leading to memory reconsolidation theory (Sara, 2000) are at the root of a key development in the understanding of the mechanisms of therapeutic change: experiential coupling (acoplamiento experiencial, see below, Bleichmar, 2001). | ||||

| • | The LeDoux Group (Schiller et al., 2010) verified empirically Bleichmar’s theory of experiential coupling, giving it external validation. | ||||

Within this context of open dialogue between disciplines, we have developed our contribution, moments ofhigh receptiveness (MoHR). It is based on two of the above concepts: experiential coupling (Bleichmar, 2001), from which MoHR is derived, and the present moment, which encompasses MoHR (Stern, 2004). We will use clinical examples to define its utility (thus becoming an opportunity for explicit and implicit knowledge integration), and to discuss the technical implications of MoHR to promote active change in therapy.

The Origin of the Concept of Moments of High Receptiveness (Mohr)

The concept of MoHR was derived from experiential coupling (Bleichmar, 2001), which was exemplified in cases of alcohol addiction: “… the procedural component (the pleasure taken in drinking) is only open to interpretation if it is relived, if the sensation is re-experienced, (re) activating the memory and entering what is called the labile state of memory, where, as we know from various neuroscientific studies, memory is reconsolidated … it is reconstructed, thus allowing, at that moment and only then, the incorporation of elements contributed by interpretation.” (http://www.aperturas.org).

Experiential coupling differentiates between two types of moments with regard to interpretation: one, the MoHR, in which procedural memory enters a labile state, and the other, of low receptiveness, in which the same interpretation with identical motivational valence (Bleichmar, 2004) would be ineffective to change because the experiential or procedural component was absent.

Conceptual Placing of Moments of High Receptiveness with Respect to the Developments of Stern and the Boston Change Process Study Group (Bcpsg)

Moments of High Receptiveness describes a transitory state of the patient in treatment that facilitates the capacity of certain interventions by the therapist to produce change. High receptiveness facilitating change can be derived not only from the therapeutic bond but also from conditions arising outside the bond or even the interpersonal relationship, such as the effects of certain dreams.1

The concepts of now moments and moments of meeting developed by the Stern group (Stern et al., 1998) refer to change as it is produced in and by the therapeutic relationship. Therefore, they correspond to only one of the factors of therapeutic change.

Figure 1 represents the relationship between the developments of Stern (2004) and MoHR. Moments of high (and low) receptiveness are subtypes of present moments. MoHR encompass both now moments (Stern et al., 1998; Stern, 2004), and moments of meeting (Stern et al., 1998; Stern, 2004).

Figure 1 PRESENT MOMENT SUBTYPES

Moments of High Receptiveness (Mohr):Definition

Moment of High Receptiveness may be referred to as a subtype of present moments (as defined by Stern, 2004). Multiple mnestic elements (semantic and/or procedural; implicit and/or explicit) are activated either spontaneously (as in now moments) or via different stimuli. These bring about a temporary window during which, irrespective of the motivational valence of an intervention (Bleichmar, 2004), the patient is in state of higher receptiveness (with greater potential to produce change). Receptiveness is specific in terms of producing change (or harm) in certain emotional states or thematic areas. It is not generalized to any intervention.

This state can occur either as a result of the activation of a procedural memory that enters a labile state (see memory reconsolidation theory, Sara, patient’s mnestic network appear as new when access is unblocked by the resolution of some conflict that was impeding its appearance.

These moments also occur in situations of deficit, when certain elements have not been constituted until the moment they are put into motion in the relationship with the analyst. These are specific moments in the therapeutic relationship that enable new elements to surface because the therapeutic process, together with the features of the therapeutic relationship, allows them to be named.

We are reminded that the psyche works with multi-nodal representations (Westen, 1999). By this we mean that it is made up of groups of associated components in which semantic, sensorial, and emotional elements all participate. Each of these complex groups then communicates with other similar groups.

All of these elements may or may not be activated at a given moment by internal factors in the patient and especially by relational factors. In this sense, the therapeutic relationship in general and its specific moments in particular, possess great potential when activating or inhibiting different representational nodes. Occasionally this causes semantic components to surface, but more often it activates the sensorial and emotional factors that are present. It is this last component (the sensorial and emotional factors) that sets off MoHR and gives them their therapeutic potential.

Moments of High Receptiveness: Underlying Mechanisms

Another important aspect to consider is that of the mechanisms underlying the appearance of MoHR: These are the lessening of resistance to the therapeutic bond and the lessening of intrapsychic resistance.

| • | Lessening of resistance to the therapeutic bond, includes revelation of narcissism (rivalry or shame) or fears that impede the emergence of aspects of the self and which the individual feels are dangerous because an imagined aversive response from the other (self-conservation). | ||||

| • | Lessening of intrapsychic resistance involves the release of fear and of reliving thoughts and deregulated affective states (which harkens to Winnicott’s fear of breakdown, irrespective of the actions of the other, not only because the superego disapproves, but also to avoid reliving states of anguish or enormous neurovegetative deregulation). | ||||

These mechanisms are rarely present in isolation. Usually they appear simultaneously in variable degrees and combinations for each MoHR.

In addition to these general mechanisms, there are two types of situations that appear to be particularly important, one of which lends itself to intervention and the other to collecting information. Again, the reality of clinical situations tells us that a combination of both is usually required, but we have separated them for the purposes of illustration.

1. Situations in Which the Analyst’S Intervention is Favored by an Improvement in Motivational Valence

In this example, the patient perceives an error on the part of the therapist and brings up a feeling of having been “let down” by the therapist; this is followed by recognition of countertransference to a greater or lesser degree. A climate such as this, with a certain reversal of the narcissistic balance in the session, would probably facilitate the reception of interpretations directed at how one adapts to the desire of the other. This would especially be the case if the motivational valence of the intervention were improved by beginning the interpretation by celebrating the acquisition of the capacity to notice submissiveness and the power to bring it up with an authority figure. If this same interpretation, with the same verbal content, were carried out from an event that had taken place with an external figure who was not the analyst, in a situation that was not an analytic session, it would probably have less transformative power (unless the event could be recreated in an experiential way). What seems fundamental is that one of these interpretations/interventions was made in a MoHR, thus greatly increasing its power to achieve therapeutic change, and this effect (the increase in power to produce therapeutic change) was not provoked by the intervention itself.

2. Situations Where the Primary Focus is the Availability of Access to Semantic Nodes That Are Remote or Previously Inaccessible Due Their Emotional Unpleasantness and Where a Stimulus Encounters an Alternative Associative Network and Incorporated Them into Shared Discourse

This situation always implies the activation of the affects that kept the semantic nodes inaccessible, and the others which connect them. Therapists are not dealing with a mnestic element that is merely semantic. In these cases, the emphasis is put on collecting information together with managing (containment, exercising self-regulation) the emerging emotional elements.

Clinical Illustration

Moments of High Receptiveness and “Now Moments”

As represented by Figure 1, all now moments are MoHR, but not the reverse, as MoHR encompass a broader category. Given the inclusive nature of MoHR with respect to Stern’s now moments, it is natural that they should share their characteristics.

To demonstrate the difference between these concepts, and especially their repercussions for technique, we will take a published clinical example of a now moment and a moment of meeting between patient and therapist (Altman, 2002). Altman writes the following clinical vignette from one of his patients, Mr. P, which happened after two years of working together (p. 509):

… he came into my office one day, greeted me, and fell into a silence. It was not unusual for us to sit in silence like this. I had learned that it was usually futile for me to intervene in a silence, to ask questions or make observations. Mr. P would respond to what I said, but perfunctorily. The really meaningful and emotion-laden interchanges nearly always were initiated by Mr. P himself, so I had learned to wait.

As I sat there, I became aware of the sound of a piano coming from outside my window, playing a beautiful, mournful, poignant melody. It seemed like background music for our session; I waited for something sad to happen. Mr. P spoke: he had been listening to the new album of Emmy Lou Harris (a country music singer), and one of the songs had so touched him that he had spent an hour the previous day, alone at home, sobbing and thinking about his father. He described how beautiful the music was, how the lyrics of the song evoked the singer’s sad reflections on a man who had been fatally wounded emotionally long ago.

As it happens, I am also a fan of Emmy Lou Harris, had recently been to one of her concerts, and had been planning to go out and buy this album as soon as possible. I had not yet heard the song my patient was describing, but right after my premonition associated with the sad piano music (which meanwhile had disappeared or faded into the background), I was stunned to find that we had a shared responsiveness to this particular singer, this emotional territory from our outside lives.

I listened intently to what my patient was telling me about the song that so moved him, adding some of my own associations to the lyrics. Toward the end of the session I told Mr. P, with amazement, about my response to the piano music (he said he had not heard it), and how I shared his love for Emmy Lou Harris. He wondered if I had yet heard the song, and I told him no, but I would by our next session.

Mr. P, up to this session, was not aware of having any feelings about his father at all. His father was so emotionally distant, if not dead, that Mr. P felt his physical death would be nearly superfluous*

Later on Altman adds, “So Mr. P’s being overcome with feeling for his father was a major breakthrough (p. 510).”

Taking into account the limitations of being an outside reader, in our opinion there was a previous MoHR, which occurred in the home of the patient as he was listening to the song by Emmy Lou Harris. It may well have been this moment in which a new thematic area was opened and, above all, that gave it a measure of connection/affective charge.

Although this was picked up in the session, and this theme possibly reopened/reactivated by Altman’s self-revelation (thus creating a new MoHR), we would like to contemplate what it would have been like if Altman and Mr. P. had relived the experience together by listening to the song during the actual session itself.

According to the theory of memory reconsolidation, listening to the song together in session would reactivate the mnestic elements with a high-affective charge connected with Mr. P’s father that emerged when he listened to the song alone. At exactly that moment of high receptiveness the mnestic elements would move into a labile state. In this state, these mnestic elements would be susceptible to coupling with another different experience in order to be modified. This experience could take the form of an emotional response from Altman, lead to interpretative elements on these affects, or elicit a combination of both, etc.

The definitions of now moments/moments of meeting (of which Altman was aware) must in some way direct his point of view and orient his technique. We recognize the validity of both the focus and the technique and there are occasions when this may be the best way to take advantage of spontaneous moments produced by the therapeutic bond.

However, the concept of MoHR, which encompasses both now moments and moments of meeting (see Figure 1), offers differential elements, which give it intrinsic value. Firstly, MoHR has its origin in a theoretical concept based on neurobiology which has been endorsed on an experimental level (experiential coupling). Secondly, because it gives us the possibility of directly employing some of the given stimuli, it offers the therapist additional technical elements, which favor therapeutic change. Lastly, it provides new foundations for applying active technique to psychodynamic psychotherapy.

Moments of High Receptiveness and “Moments of Meeting”

As we have already pointed out, MoHR is a concept that encompasses moments of meeting. These ideas share characteristics, but the former (unlike the latter) can be derived from elements outside the therapeutic bond or link. Later in the article we will look into this in more depth, when we propose some ways of inducing, recognizing, and making the most of MoHR.

We will endeavor to demonstrate the comprehensive character of MoHR with an example. In order to do so, we present an ideal timing sequence in a model described by Stern (Stern et al., 1998):

| 1. | the spontaneous appearance of a now moment in the intersubjective space between therapist and patient. | ||||

| 2. | resolution by way of a specific intervention, with the therapist’s signature, in the now moment which gives rise to a moment of meeting. | ||||

Both of these moments would be MoHR.

Now let us imagine that this same sequence starts with the now moment but, rather than being followed by a response from the therapist (with all the characteristics pointed out by Stern for a moment of meeting), it is instead followed by an intervention that lacks these characteristics.

In this scenario, the difference is immediately obvious. In Stern’s theoretical model, the present moment produced would not be a now moment (it is not spontaneous, it is derived from the effects of an intervention by the therapist), neither would it be a moment of meeting.

In the model we propose, the present moment created would be a MoHR (although the elements activated may be different from those mobilized by the preceding now moment). A failed intervention, as we will see later on in triggering stimuli, also produces a MoHR, which, if it is taken advantage of, possesses great therapeutic potential.

Moments of High and Low Receptiveness

We will now examine some clinical vignettes in which the difference between moments of low and high receptiveness to intervention can be perceived.

Let us now consider the case of C, a 46-year-old woman in treatment for multiple phobias. The clinical presentation was of an intense emotional paralysis, which, at certain moments, would become a cognitive paralysis (mental block) when faced with masculine figures of authority. The patient had previously been in treatment. During that treatment she discovered some aspects of her childhood that related to a degrading father and older brothers who transferred the aggression and rejection suffered at the hand of their father to their younger siblings, C among them. We verified this recollection by the substantial evidence that emerged in treatment. However, this knowledge did nothing to stop C from experiencing the same emotional paralysis and even cognitive/mental block.

C needed to relive these sensations experientially in session (which would create a MoHR), and she also needed proposals for actions she could take in real life (Power, 2000) that would give her sufficient ego resources to make change possible. By reliving both the experiences of her childhood that caused the block and her new, real-life experiences, the information she already possessed about her childhood permeate her structure and act as preparatory step for further new experiences.

This was a complex process with regard to the number of intervening elements that produce change (exposure, learning ego resources, the comprehension of feelings and emotional states, etc.). What was previously known has a limited effect because it was suggested in a moment of low receptiveness, during which bringing the unconscious into the conscious did not overcome the symptoms. Only when interpretation joined forces with experiential coupling its effect was possible, and in this case, it was only in the MoHR that the interpretation became effective.

It could be argued that previous interpretations had not been made on the same terms, and that their motivational valences were not strong enough to produce change. The technical modifications brought into this treatment were the result of having read Bleichmar’s work (2001). While it is likely that the interventions during the first year of treatment were not exactly the same in terms of motivational valence, it is difficult to attribute the change to these differences or any other single element. We questioned this mechanism because the change experienced by the patient was not only behavioral, but also because of the symbolic and procedural modification of the codes through which she related to herself and reality. Bleichmar calls this “passionate belief matrixes” (creencias matrices pasionales, revised by Méndez and Ingelmo, 2011).2

Continuing with the description of the evolution of the clinical case, C successfully adapted to a new work environment, with a new boss and workmates. She also separated from her partner and explored other possible romantic relationships, including blind dates through a social networking service. As evidenced both by her romantic separation and in subsequent relationships, she experienced a sense of value in herself and of having something valuable to offer others. This has allowed C to approach romantic relationships with men differently; her attention was not focused solely on the possibility of rejection as it had been in the past. This anxiety, which had been dominant most of the time, usually led to an almost automatic sense of paralysis. After our work, C was able to see herself as someone worthy of attention, and she was able to act on whether to accept or reject the offer of a relationship.

M, a woman of 52, had a borderline personality disorder in which dissociation constituted a noticeably prevalent mechanism. In one session we were going through some photos from her adolescence, and she found one in which she has long black hair. It brought on the following association: “I look at this photo and I remember the feeling of brushing my long hair, how I felt when I left the house to go out. It was a bone of contention between my mother and I, who thought it unrefined (here M. clarified that her mother believed hair should either be worn short or tied back). P, my boyfriend at that time, loved my hair but my mother said it was gypsy like. I responded by saying that P loved gypsies and thought them the most beautiful women in the world.” The contemplation of the photo vividly evoked the memory of brushing her hair in her youth that created the MoHR.

At that moment, M brought up an instance in which she cut off her hair3 as a self-aggressive behavior in response to feeling rejected by her husband; it added a link to previous interpretations regarding her reaction to abandonment, “I leave them before they can leave me,” and the cutting of her hair, “When I see my hair going gray, how it has lost the vitality it had before, it doesn’t feel like my own hair anymore.” The photo brought up, in connection with an affectively charged memory, both the feeling of narcissistic possession that M’s long hair represented and the feeling of loss with the passing of the years. This in turned opened the possibility of dealing with age and the fear of deterioration, a fear which was multiplied because M’s mother had Alzheimer’s disease. None of the previous work done with M—encouragement of self-observation, provision of framework in which to view herself—would have had the same effect on her had she not experienced that state of high receptiveness triggered by the photograph and the memory it provoked4.

It is worth noting that the mnestic-semantic component alone does not constitute a MoHR. The experiential component is paramount, and not only because it is the motor that sets in motion the MoHR, but also because it is indispensable that patients feel themselves to be the subject of the action. The high motivational valence of the memory of that experience, due to the quality of the emotion, resolves the patient’s defenses against this memory. We could say that one cannot deny what one is feeling at that very moment while observed by another. To illustrate what we have just said, consider the emotional experience involved in carrying out an ultrasound on a pregnant woman. The experience of being pregnant is undeniable for both; it is “beyond all doubt.” So, what is central from that experiential moment on is how to deal with this experience, how to go ahead or interrupt the process, how to begin the additional care of the fetus or the mother, etc.

Let us now consider an additional clinical vignette of the M case. Her account of motherhood lacked an associated emotional component; it was purely semantic, told in a flat tone of voice when she recalled both good and bad events, but particularly on the bad events. One day in session, M made reference to a book she was reading: “… there is scene that has something to do with me but I don’t know what it is.”

I asked her to read aloud that part of the text that affected her. In the story, a mother and her 10-year-old son take a trip to a lake. While the son splashes about in the water, the mother experiences a panic attack described as enveloping black waves and earth trembling beneath her feet. In a daze, she can hear screams for help from her son but cannot respond to them until a hiker intervenes, and though he tries to save the boy, it is too late, the child dies. The hiker asks the mother “Why didn’t you scream?” Later in the novel, the woman experiences headaches, nightmares of being trapped in terror, and that “her head was filled with screams.”

After reading the text in my office and trying to connect with the emotions in it, M recalled the following “forgotten” memory: “I was at a house with a swimming pool, accompanied by some friends. My one-and-half-year-old son was playing at the edge of the pool, which was still dirty from the winter months. I had to go into the house and go up to the second floor. I checked on him before going in. There were other adults in the garden. Once I was upstairs, I went over to the window, I was feeling uneasy, and I saw him fall in headfirst. I didn’t scream. I ran back downstairs and threw myself into the pool shouting ‘Oh my God!’ I got him out, although I needed some help, and gave him mouth to mouth resuscitation and he recovered. For a long time afterwards, when I closed my eyes the scene would reappear in my mind and I would be overwhelmed by a feeling of panic.”

A whole world of repressed emotions opened up. The activation of the semantic, sensorial, and emotional aspects of this representation set in motion a chain of activation of other representational nodes that shared a closeness or similarity. The situation opened a discussion of the times when motherhood was distressing for M. She told of how her second child had febrile convulsions and how there had been a period during which she would phone his nursery more than 10 times a day to see how he was. On one occasion she commented, “I was driving to a telephone box to call the school to check on the children, and I was in such state by the time I got there that I ran straight into it… It was a difficult time, it was lucky that the head of the kindergarden knew how to deal with it and was able to calm me down.”

Rereading the text in session created a MoHR in which M was able to connect with her feelings of anxiety associated with maternity. This in turn opened the door to another related, and even further distant, feeling: her mothering relationship with her younger siblings. We must consider that M had to look after five siblings when she was barely 10 years old. As adults M’s siblings had lives filled with conflict. They were probably marked by their bond with their neglectful parents and where M, in the substitute-mother role, proved insufficient. Furthermore, this had the effect of a double trauma for M; she not only had feelings of guilt and abandonment for failing her siblings, but also she failed to register her own abandonment at having to take on the adult role. It is likely that this reinforced the mechanisms of dissociation, as perceiving her own anguish in this scenario presented a threat to her integrity and her efforts in that role.

In another session we used a photo from M’s childhood. In it she is sitting in the center of the picture, holding her youngest sister on her lap; the rest of her younger siblings surround her. Working with this photo had a similar effect to reading the passage from the novel. It created a MoHR, and this allowed us to reconnect to an emotional state, which in turn accessed other dreams and associations. The result was an amplified capacity for M to connect with her feelings of anguish and her need to be taken care of, both of which had been practically nonexistent until that moment.

The vignette emphasizes the enormous effectiveness of MoHR in achieving therapeutic change that is caused by feelings that are undeniable to the patient and the therapist. This is because the feelings are manifested in the context of the session and because of their vivid and experiential character. The clinical work no longer consists of overcoming resistance to these feelings; rather the feelings acquire the character of known facts. Irrespective of the strong evocative power and the painful feelings MoHR may give rise to, we can work from there, going back at different points in subsequent work and evoking these moments, to take up another aspect of them again. We want to stress that using it as an experiential bookmark in the therapeutic process allows us to regulate the amount of emotion that our patient can tolerate in any given time.

We are talking about a situation that encompasses the patient and the therapist, the transferential-countertransferential processes, and the surrounding environment.

An example of the differences between moments of low and high receptiveness is the difference between telling about a dream in the conventional way in the past tense and telling about the same dream in the present tense, in an experiential way (de Iceta & Méndez, 2003). In the first scenario of [telling about] the dream, certain associations come across. When the dream is told again as if it were happening in the now, thus increasing the experiential nature of the telling, the number of active mnestic elements is amplified and new associations, along with new connections, appear. The result is that the appearance of this new material, together with its new experiential quality, increases the receptiveness to the technical interventions referring to these elements of “new appearance.”

In short, we are looking at the old Freudian difference (1915), by referring to mental content—between what is experienced and what is heard—as very different ways of processing and working with representations. We would then say that states exist in which receptiveness or accessibility is high, as opposed to others which do not provide these conditions. We are not referring to a general receptiveness/accessibility, but one that is concrete and specific, and tied to contents that are linked by unconscious processes active in that moment.

It is up to the therapist to take advantage of these accessible moments, however, because MoHR are moments of high vulnerability for the patient, there is a substantial risk of iatrogenic consequences. We draw a parallel between the dose of medication to be administered either orally or intravenously; the former allows for a wider dose adjustment, but change is slower; the latter is faster and more efficient with regard to change, but requires much finer adjustment because of the higher risk of inflicting harm.

Other Clinical Examples of Moments of High Receptiveness

Other mechanisms for change aside from interpretation, such as the après-coup phenomenon5 (see the revision of the concept in Faimberg, 2005), constitute MoHR. Let us remember Freud’s initial description of the après-coup (although the definition of the term postdates him as pointed out by Faimberg, 2005). In Freud’s account, a patient contemplates a scene in which her father molested her young cousin. This recollection caused the patient to resignify how her father had previously approached her, which, until that moment, had lacked sexual significance in her coding. The moment caused by contemplating this scene included the appearance of certain affective states (perhaps sexual arousal, envy, fear, rage, or others) and the connection between certain mnestic, semantic, and procedural elements (perhaps the memory of some details regarding the overtures, specific sentences, attitudes, aromas). These were probably of an intensely experiential nature, and may have appeared to the patient as if they were happening at that very moment. A moment such as this allows for a great change in the patient’s mental life.

These types of therapeutic situation, in which après-coup or similar phenomena appear, can occur spontaneously or can present themselves when therapists encourage patients to provide material of great emotional value, such as something they have read or photos. Situations like these, which involve MoHR, present opportunities in which to introduce interpretations whose contents are very specific to the phenomena in question. These interpretations may concern certain physical symptoms, sensations, and intensely relived memories.

In the example above, an interpretation, which included the verbal recreation of certain physical symptoms and how they related to having suffered sexual abuse during childhood, is received with heightened receptiveness by the patient. Conversely, we consider that receptiveness would have been low had the interpretation been given without contemplation of the scene, or sometime after its contemplation, while attempting to keep the memory hidden.

Implications for Active Technique

Active Evocation of Moments of High Receptiveness

Even though our approach to working with MoHR is within psychodynamic psychotherapy as defined by Blagys & Hilsenroth (2000); MoHR can occur in any therapeutic encounter regardless of the theoretical orientation of the therapist. In fact, they can even occur outside the therapeutic space. As mentioned previously, MoHR are susceptible to being evoked or produced by different mechanisms or stimuli. The following list is a partial list of some of these:

Visual images — These include the use of photos as mnestic stimuli; Freud frequently asked patients for photos and mementos. It also includes using the cinema as a therapeutic instrument.

Smell – Scent is highly evocative and of great relevance to many patients with posttraumatic stress. Patients who have been victims of fire, for example, find the smell of burning intensely evocative. Smell also may be a trigger in patients who have suffered sexual abuse, for example, when exposed to the abuser’s cologne.

Sound — Music can conjure memories, as the Emmy Lou Harris song did in the case of Mr. P presented by Altman (2002).

Texts — Rereading books (as in the M case, when the patient refers to excerpts of a book), letters, or case history, may access a moment of high receptiveness.

Disruptive moments in the therapeutic process due to errors on the part of the analyst – These are moments in the transferential-countertransferential process during which an element of self-revelation by the analyst opens treatment to new emotional elements that connect to situations important to the patient.

Interpretations adequate in terms of semantic and emotional content, and timing — These occur right after that a new emotional state with new associations emerging configure a moment of high receptiveness. At this point, the only risk is the therapeutic enthusiasm on the analyst, if he/she ignores the emotional impact on the patient. One could remark the insight achieved, put an experiential bookmark and work on self-regulation.

Moments of meeting — These are quite the same as in the previous point (including the risk on the analyst).

Dreams — These are especially useful when working in the present tense and trying to obtain the most experiential memory possible (see de Iceta & Méndez, 2003).

Events in the patient’s reality — These include trips, passing by certain places, reunions, contact with events in the lives of significant people, including those that occur in the life of the analyst, for example, a therapist’s pregnancy, maternity/paternity leave, mourning the passing of a loved one, absence due to attending a conference (Fried, 2008) or a serious, possibly terminal illness (Brokaw, 2008).

Variables prior to treatment — These triggers can involve contacts that may have influenced the patient before beginning therapy, such as the person who recommended the therapist or the prestige of the therapist.

Initial interview — With all the variables in play during a first meeting (environmental and personal factors, managing anxiety, etc.), it is possible that one of these will elicit a MoHR.

Group interviews with emotionally significant people for the patient — These people include parents, partners, etc.

There are many factors that can work as triggering stimuli. However, irrespective of the nature of the stimuli, different mnestic elements are activated (procedural and semantic), with a noticeable variation in terms of the intensity of the affective state they provoke (higher or lower). The higher the number of mnestic elements activated, the higher the receptiveness, or the greater the potential for change. This is because of an increase in the number of thematic areas that can be approached in that moment, regardless of those that are to be worked on in that specific moment of the therapeutic process.

Some Characteristics of the Therapist for Recognizing and Using of Moments of High Receptiveness

There are two previous conditions to active use of MoHR: to work in the context of the analytical relationship and to develop a secure attachment link or bond. The therapist should ideally have:

| • | Theoretical foundation— what is unknown cannot be perceived. | ||||

| • | Empathy and self-knowledge | ||||

| • | Flexibility | ||||

The analyst needs to acknowledge flexibility in the practice of psychodynamic therapy and recognize the inevitability and the value of the process of negotiation that takes place in each analytic dyad. Greenberg (1995) refers to this as the interactive matrix, and argues that the framework itself and the “rules” change depending on the specific nature of the subjectivities of the analyst and the patient. In his writings about professional limits, Gabbard and Lester (2002) argued that to avoid the dangers of defensive rigidity, analysts should conceptualize the analytic limits as fluid and related to the contextual aspects of a particular analytic dyad (Gabbard and Lester, 2002). Other authors (Bass, 2007; Labor, 2007) stress this point.

This change does not mean that the analytic session is a “free for all.” However, it is true that the rigid adherence to a technical posture which does not stretch to finding an interpersonal “space” that is sufficiently comfortable for both participants can often be as anti-therapeutic as “wild analysis.” This space involves the patient in the kind of creative, interpersonal negotiation that we hope to encourage in their other relationships. According to Mitchell (1997), negotiation and mutual adaptation are fundamental for therapeutic action. He points out: “There is no general solution or technique, because each resolution, by its very nature, must be custom designed. If the patient feels that the analyst is applying a technique or displaying a generic attitude or stance, the analysis cannot possibly work” (p. 58). This process of one mutually entering the subjective experiences of the other finally leads to the emergence of what Mitchell (1997) calls “something new from something old” (p. 59), which he considers to be the central mechanism of therapeutic action.

| • | Capacity for optimal responsiveness (Bacal & Herzog, 2003) The analyst’s capacity to respond must be based on his or her knowledge that the therapeutic process operates on a complex system of reciprocal relations unique to each analyst-patient partnership. Therefore, the analyst’s task is to offer responses that, consistent with his or her capacity for that particular patient, facilitate therapeutic interaction optimal for the therapeutic progress of the patient. Specificity theory tells us that there are infinite possibilities for therapeutic interactions in the analytic dyad and that it is not just the traditional methods of capacity to respond that should be considered for their possible efficacy. This invites the therapist to widen the direct use of his or her empathic knowledge to help choose from the numerous verbal and non-verbal responses available. This also requires the therapist to carry out a careful follow up of how his or her responses to the psychological needs of the patient have been perceived. Specificity theory legitimizes the analyst’s attempt to adapt the treatment in such a way that it is most useful in terms of the patient’s therapeutic necessities, that it works to improve the balance between analyst and analysand, while at the same time recognizing the inherent limitations of a particular dyad in doing so. Furthermore, specificity theory opens new channels for the formal discussion of crucial therapeutic interventions that were previously considered outside the reach of formal analytic discourse. | ||||

| • | Scientific attitude We agree with Renik (2000) that supervising the spontaneous, the nonstandard technique, with a close follow up of the impact for the patient and the therapeutic process, is essential, particularly if the iatrogenic potential with certain interventions is considered. | ||||

How to Identify a Moment of High Receptiveness

This is a topic of seminal interest in directing future research and is based on the detailed observation of verbal and nonverbal communication between patient and therapist. Likewise, both aspects should be the base of the training of future psychotherapists and in supervision during psychotherapy practice.

We offer some useful guidelines for the recognition of a MoHR. As in Stern’s now moment (2004), MoHR fulfills the characteristics that define it. These are:

| 1. | It is an affectively charged moment as it calls into question the nature of the patient-therapist relationship. | ||||

| 2. | It generally bumps up against (or threatens) the setting; how the patient and therapist will “be and work together” from that moment on is in play. | ||||

| 3. | The level of anxiety in both the patient and the analyst builds. Both are forcefully dragged to the here and now. | ||||

| 4. | The therapist feels that a routine technical response is not sufficient. This increases his or her anxiety. | ||||

| 5. | A crisis has been created that needs to be resolved. This resolution may come in the shape of a moment of meeting or an interpretation. | ||||

A fact common to all these situations is that a noticeable change in the emotional climate of the session is invariably produced, either in intensity (increased or decreased) or in the quality of the dominant affective state. The degree of change in the tone or quality of the emotion should alert the analyst to the possibility of a MoHR.

Other indicators may be those that have traditionally been considered for recognizing a good interpretation, such as the appearance of new material of new associations (Etchegoyen, 1998). In addition, the knowledge of stimuli for active evocation (see above) necessitates the therapist be alert so that when they are presented it will be possible to choose one of the ways to make use of them. Likewise, it is useful for the therapist to have an open and attentive attitude towards oddities and unexpected components.

Making the Most of a Moment of High Receptiveness

As a coda to this paper, here are some suggestions to make the most of MoHR.

The first thing that must be pointed out with regard to MoHR is the risk of iatrogenic effects. As these moments leave the patient open to change, vulnerability is at a maximum, thus requiring the greatest delicacy and rigor on the part of the analyst when making an intervention.

We warn against techniques that seek intensity for the sake of intensity as an end in itself; we stress that heightened emotional intensity does not always bring about higher receptiveness. Although a certain amount of anxiety is necessary to work, when this goes past a particular threshold (which is variable in each case), it becomes unmanageable for both patient and analyst, and it obstructs the progress of the therapy (Bleger, 1964). Applying this type of technique must be specifically adapted to the patient, the therapeutic relationship, and the clinical situation6.

Consider the possibility of refraining from inducing a MoHR and “saving” the material to induce a receptive moment with the appropriate emotional intensity. To do this it is essential that a secure patient-therapist bond exists. In addition, we also need information regarding the vulnerability of the patient, his or her capacity to tolerate situations of emotional intensity or the significance (with its resulting intensity) of a certain emotion that the therapist may have been able to obtain in the course of the therapy.

Given the unique and specific nature of MoHR, there is no model intervention. The moment of receptivity is generated from the specific determinants of each case, taking into consideration the motivational systems active at that time in the therapeutic process. It is indispensable to work from the particular characteristics of the patient and therapist.

With the aforementioned provisos, we offer some suggestions we consider useful when trying to make the most of a MoHR.

Acknowledge MOHR as such. It is not necessary (or indeed advisable/beneficial or possible) to use everything these moment bring up in just one session. It can be particularly useful to establish some sort of shared experiential bookmark, which can be returned to in the future (for example, evoking family interviews in subsequent work with an adolescent).

Work on psychobiological self-regulation. It is important to keep at the forefront that high receptiveness implies high vulnerability. One must be especially attentive to the “dose” administered to the patient; do not offer all the information at that moment simply because a window is opened. Calibrating the interpretations and helping the patient to self-soothe can be invaluable interventions for the experiential learning of self-regulation.

Take this exceptional opportunity for the resolution of dissociation (either ideo-affective or other). The presence of both in the moment makes them undeniable for the patient and therapist.

Experiential coupling. – as Bleichmar suggested in working with addictive behaviours (see above).

Extinction – (see the work of the LeDoux’s group, Schiller et al., 2010).

Reinforcement/setting up of the self as subject of action, efficiency as subject of action – for example, in Altman’s case the ability of Mr. P to access on his own to extremely painful feelings on his father, helping therapy progression.

Working on emotional sequences – Due to its special interest, we would like to further develop the use of MoHR in psychotherapeutic work on emotional sequencing in a subsequent study.

We would like to stress that while we referred to MoHR within psychodynamic therapy, this mechanism of change may occur in other forms of therapy, as well as outside of therapy. Due to its focus on the therapeutic relationship, psychodynamic therapy may offer a better setting to minimize the risks associated to active technique. We would like to close by clarifying that we do not consider that therapeutic change occurs exclusively in MoHR ([as other authors have pointed out with respect to the work of Stern] (Orange, 2008).

(2002). Where is the Action in the “Talking Cure”? Contemporary Psychoanalysis, 38:499–513.Crossref, Google Scholar

(2003). Specificity Theory and Optimal Responsiveness: An Outline. Psychoanalytic Psychology, 20: 635–48).Crossref, Google Scholar

(2007). When the frame doesn’t fit the picture. Psychoanalytic Dialogues, 17:1–27.Crossref, Google Scholar

(2000). Distinctive activities of short-term psychodynamic-interpersonal psychotherapy: A review of the comparative psychotherapy process literature. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice, 7, 167–88.Crossref, Google Scholar

(1964) Psychological interview: Diagnostic use. La entrevista psicológica: su empleo en el diagnóstico. Buenos Aires: Universidad de Buenos Aires.Google Scholar

(1997) Advances in psychoanalytic psychotherapy: towards a technique of specific interventions. Avances en psicoterapia psicoanalítica: Hacia una técnica de intervenciones espeafícas. Buenos Aires: Paidós.Google Scholar

(2001) Therapeutic change on the light of current knowledge on memory and múltiple unconscious processing. El cambio terapéutico a la luz de los conocimientos actuales sobre la memoria y los multiples procesamientos inconscientes. Aperturas psicoanalíticas (No. 9, Nov 2001) http://www.aperturas.orgGoogle Scholar

(2004). Making conscious the unconscious in order to modify unconscious processing: Some mechanisms of therapeutic change. International Journal of Psycho-Analysis, 85:1379–400.Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

(2008). Winter meets its death. Psychoanalytic Inquiry, 28:599–611.Crossref, Google Scholar

(2003) Dream analysis in the modular-transformational approach: a proposal for a specific technique. El análisis de los sueños desde el enfoque Modular-Transformacional: una propuesta para una técnica especifica. Aperturas psicoanaliticas (No. 13, Marzo 2003) http://www.aperturas.orgGoogle Scholar

(1998) Fundamentals of psychoanalytic technique. Los Fundamentos de la técnica psicoanalítica. Madrid, España: Amorrortu editores.Google Scholar

(2005). Après-coup. International Journal of Psycho-Analysis, 86:1–6.Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

(1915). The unconscious. Lo inconciente. En: (Complete Psychological Works) Obras Completas T.XIV, Buenos Aires, Argentina: Amorrortu Editores, 1979.Google Scholar

(2008). The sweet cheat gone: here and there—elation, absence, and reparation. Canadian Journal of Psychoanalysis, 16:3–22.Google Scholar

(2002). Boundaries and Boundary Violations in Psychoanalysis. Washington, DC. American Psychiatric Publishing, Inc.Google Scholar

(1995). Psychoanalytic technique and the interactive matrix. Psychoanalytic Quarterly, 64:1–22.Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

(1993). Facilitating emotional change. the moment-by-moment process. New York: The Guilford Press.Google Scholar

(2007). In search of memory: the emergence of a new science of the mind. En busca de la memoria. El nacimiento de una nueva ciencia de la mente. Katz Barpal Ed. BUENOS AIRES.Google Scholar

(2002). Après-coup. In: de Mijolla A, editor. International dictionary of psychoanalysis Dictionnaire international de la psychanalyse. Paris: Calmann-Levy.Google Scholar

(2011). Passionate beliefs matrixes from an intersubjective perspective Las creencias matrices pasionales desde la perspectiva de la intersubjetividad. Aperturas Psicoanalíticas, n° 39 (Noviembre 2011). http://www.aperturas.orgGoogle Scholar

(1997). Influence and autonomy in psychoanalysis. Hillsdale, NJ: The Analytic Press.Google Scholar

(2008). Recognition as: Intersubjective vulnerability in the psychoanalytic dialogue. International Journal of Psychoanalytic Self Psychology, 3:178–194.Crossref, Google Scholar

(2000). “On trying something new: Effort and practice in psychoanalytic change”. Psychoanalytic Quarterly, LXIX (3): 493–526.Crossref, Google Scholar

(2000). Personal and professional life. In J. J. ShayJ. Wheelis (Eds). Odysseys in Psychotherapy (pp.312–336). New York: Ardent Media.Google Scholar

(2000). Strengthening the shaky trace through retrieval. Nature Review: Neuroscience, 1, 212–3.Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

(2010). Preventing the return of fear in humans using reconsolidation update mechanisms. Nature. 463(7277): 49–53.Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

(2003). Affect Regulation and the Repair of the Self. New York: Norton.Google Scholar

(2010) The Efficacy of Psychodynamic Psychotherapy. American Psychologist, 65, 2: 98–109.Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

(1998). Non-interpretative mechanisms in psychoanalytic therapy: the “something more” than interpretation. International Journal of Psycho-Analysis, 79, 303–36.Google Scholar

(2004). The present moment in psychotherapy and everyday life. New York: Norton.Google Scholar

(2009). A new direction for psychoanalysis: in search of a transference of health. International Journal of Psychoanalytic Self Psychology, 4S:31–43.Crossref, Google Scholar

(1999). The scientific status of unconscious processes: Is Freud really dead? Journal of the American Psychoanalytic Association, 47, 1061–106.Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar