Role Expectancies, Race, and Treatment Outcome in Rural Mental Health

Abstract

This study is the first report examining the relationship between pretreatment expectancy and treatment outcome in Osage Native Americans receiving mental health services. Results reveal that in Native American participants, high expectations for advice and approval in therapy may lead to poor treatment outcomes. Conversely, low expectancies may be risk factors for poor outcomes among White American individuals. Therefore, practitioners should consider client race during assessment and appropriately address problematic pretreatment expectancies to prevent poor treatment outcome. Given differences in direction of effects between races, it may be best to increase advice and approval therapeutic roles when working with Native American clients, whereas it may be best to increase pretreatment expectancies with White American clients. Results are particularly notable given that Native American clients are pervasively under-researched and under-served.

Introduction

Client expectations during psychotherapy are important elements of the process and outcome of treatment. This includes role expectancies, defined as beliefs held by the client and therapist about the parts they are to play during treatment. These may include, for example, the client’s expectations of independence in decision making or how directive the therapist is expected to behave during session. One of the most commonly used measures of role expectancies, the Psychotherapy Expectancies Inventory-Revised (PEI-R) was created based on four components of role expectations including “nurturant” (guidance and support from provider), “critical” (constructive feedback), “model” (providing instruction so that the clients may help themselves), and “cooperative” expectations (equality of client to provider; Bleyen, Vertommen, Vander Steene, & Van Audenhove, 2001). Previous researchers have reported a robust link between greater client role expectancies and stronger therapeutic alliance (Patterson, Uhlin, & Anderson, 2008) and treatment outcomes (Aubuchon-Endsley & Callahan, 2009).

With respect to racial minority clients (i.e., racial groups that are disadvantaged regarding social status, education, employment, wealth and/or political power, including: American Indian and Alaska Native, Asian, Black or African American, Hispanic or Latino, and Native Hawaiian and Other Pacific Islander clients), previous research has found that race is associated with treatment outcome (see Fuertes, Costa, Mueller, & Hersh, 2005 for detailed review). In particular, racial minority groups may be more likely to be misdiagnosed (e.g., over diagnosis of psychotic spectrum disorders based on cultural perceptions in Hispanic and Native American clients) and receive inappropriate mental health services (e.g., greater rates of involuntary hospitalization in African American clients). In addition minority groups have fewer improvements in symptomology, for example, Beck Depression Inventory-2nd Edition [BDI-II] and Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression [HRSD] scores decreased less for African American clients in Cognitive Behavioral Therapy and Interpersonal Psychotherapy than for White American counterparts (Cort et al., 2012; Markowitz, Spielman, Sullivan, & Fishman, 2000). These poorer treatment outcomes may be mediated by treatment barriers such as worldview or language differences between provider and client, discrimination, fear/mistrust of providers (Smedley, Stith, & Nelson, 1999), and difficulties establishing a working alliance (Walling, Suvak, Howard, Taft, & Murphy, 2012). Although these phenomena may be partially explained by mismatch in race or ethnicity between provider and client, the current literature suggests highly variable effect sizes of this matching across studies (see Cabral & Smith, 2011 for systematic review and meta-analysis). It has also been reported that cultural (i.e., cultural commitment, acculturation, and cultural explanations and perceptions of mental illness) and historical factors (i.e., local or regional mental health research or clinical service provision with racial minority groups) may influence clients’ perceptions of therapy (Romme, 2000; Zane, Nagayama Hall, Sue, Young, & Nunez, 2004), their treatment compliance/engagement, or their role expectancies (Bhugra, 2006). However, to date no research has examined whether there is a link among these distinct findings specifically within the understudied Native American client population. This omission is a significant research gap given reports that Native American clients may have unique treatment expectancies (e.g., expected guidance drawn from the provider’s personal life lessons, unconditional acceptance and respect, and an integration of spirituality in treatment) leading to differential therapeutic outcomes (McCabe, 2007).

Treatment Expectancies and Outcomes Among Native American Clients

It is possible that different expectations and outcomes are the result of dissimilarities between White American and Native American views and values (Zane et al., 2004). For example, several common therapy components as conceptualized within Western societies, such as, individual problem focus, encouragement of affective expression, and self-disclosure, may inherently conflict with views and expectations in Native American culture (Gone, 2007). Additionally, historical factors may lead to expectations of less trust and/or understanding within the therapeutic relationship or based on receipt of traditional services in the past, greater expectations of the therapist’s role in treatment (Smedley et al., 1999). Therefore, the purpose of the current study was to investigate a sample of Native American participants receiving clinical treatment to determine whether there were racial differences in the relations between pretreatment role expectancies and treatment outcome in an under-researched clinical setting (rural community mental health clinic) where Native Americans typically access mental health services.

Hypotheses

Considering the existing literature summarized above, it was hypothesized that Native American participants would have (1) greater expectancies of the role of their therapists (i.e., they would expect therapists to display greater guidance, feedback, advice, and instruction), (2) more traditional Native American cultural values, and (3) worse treatment outcome. It was also hypothesized that (4) there would be differences in treatment outcome associated with participant–therapist racial match and (5) there would be racial differences in the relationship between treatment expectancies and outcome. Although existing research does not elucidate a clear theoretical model of such relationships, previous findings suggest a more robust relationship between negative pretreatment role expectancies and poor treatment outcomes in Native American clients when compared to their White American counterparts.

Methods

Participants

The sample consisted of 65 adult participants treated in a rural community mental health clinic (see Table 1). Seventy-one percent of participants had previously utilized mental health services, though not at this newly established clinic. We determined that 65 participants were sufficient for the first two hypotheses because a priori power analyses using G*power version 3.0.10 (Faul, Erdfelder, Lang, & Buchner, 2007), suggested a sample size of 62 is sufficient to complete one-tailed independent sample t-tests with the following parameters: d = 0.80 (large effect size, as in previous studies), α = .05, and allocation ration = 4. For hypotheses 3 and 4, a priori power analyses suggested that a sample size of 39 would be sufficient to complete chi-square tests of association with the following parameters: w = 0.50 (large effect size as in previous studies), α = .05, and df = 2. Because there was not enough statistical power to complete analyses testing hypothesis 5, a resampling method (bootstrapping) was applied to increase the size of the dataset for analyses.

| Descriptive Variable | Total Sample (n = 65) | Native American Participants (n = 13) | White American Participants (n = 52) | Racial Differences |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean Age (SD) | 36.1yrs. (11.0yrs) | 31.9yrs. (11.8yrs) | 37.2yrs. (10.7yrs) | ns |

| Mean Education (SD) | 12.0yrs. (2.1yrs.) | 11.5yrs. (1.7yrs.) | 12.2yrs. (2.2yrs.) | ns |

| Mean Income (SD) | $21,351 ($44,216) | $19,429 ($35,907) | $21,784 ($46,393) | ns |

| Gender | ns | |||

| Female | n = 46 | n = 9 | n = 37 | |

| Male | n = 18 | n = 4 | n = 14 | |

| Marital Status | ns | |||

| Married | n = 24 | n = 6 | n = 18 | |

| Separated | n = 4 | n = 0 | n = 4 | |

| Divorced | n = 12 | n = 2 | n = 10 | |

| Widowed | n = 2 | n = 0 | n = 2 | |

| Single | n = 18 | n = 4 | n = 14 | |

| Employment | ns | |||

| Employed | n = 31 | n = 8 | n = 23 | |

| Unemployed | n = 21 | n = 5 | n = 16 | |

| Primary Diagnosis | ns | |||

| Mood Disorder | n = 33 | n = 7 | n = 26 | |

| Anxiety Disorder | n = 17 | n = 2 | n = 15 | |

| Impulse Control/Attention Disorders | n = 8 | n = 0 | n = 8 | |

| Substance Use Disorder | n = 0 | n = 0 | n = 0 | |

| Psychotic Disorder | n = 3 | n = 1 | n = 2 | |

| None | n = 3 | n = 2 | n = 1 | |

| Comorbid Diagnosis | ns | |||

| Mood Disorder | n = 16 | n = 3 | n = 13 | |

| Anxiety Disorder | n = 23 | n = 3 | n = 20 | |

| Impulse Control/Attention Disorders | n = 7 | n = 2 | n = 5 | |

| Substance Use Disorder | n = 2 | n = 0 | n = 2 | |

| Psychotic Disorder | n = 1 | n = 0 | n = 1 | |

| None | n = 14 | n = 4 | n = 10 |

Table 1. DEMOGRAPHIC DESCRIPTIVE STATISTICS IN THE ORIGINAL SAMPLE

There were no significant differences in age, years of marriage, years of education, or annual income between Native American and White American participants (see Table 1). Distributions of sex, diagnoses, and employment status were similar in both samples (≈70% women, ≥50% had a primary diagnosis of a mood disorder, and ≈40% were unemployed; see Table 1). The two therapists for each group included a Native American Licensed Clinical Social Worker (MEducation = 8 years) and a White American advanced doctoral student in Clinical Psychology (MEducation = 7 years). Both providers were trained in and utilized evidence-based practice with primarily cognitive-behavioral interventions. This demographic information was used to explore differences in treatment expectancies or outcome based on participant–therapist match (Zane et al., 2004).

Materials

Participants completed a questionnaire about demographics and treatment history, the PEI-R (Bleyen et al., 2001), and the Orthogonal Cultural Identification Scale (OCIS; Oetting & Beauvais, 1990).

PEI-R

The PEI-R is a 24-item self-report measure of role expectancies, which includes the following scales: approval-seeking, advice-seeking, audienceseeking, relationship-seeking and impression-seeking (Bleyen et al. 2001). Higher scores indicate a greater expectation of the therapist to be nurturing or approving of the participant, to provide the participant with advice, genuinely listen to the participant’s concerns, and to foster a relationship that supports openness and honesty.

The PEI-R has adequate reliability (reported α for subscales from .75-.87, obtained α in current sample for subscales from .68-.94) and predictive utility for identification of attrition (Aubuchon-Endsley & Callahan, 2009). The use of a reference range (85.36-126.30) on the PEI-R was found to have good specificity (.93) in identifying premature termination (Aubuchon-Endsley & Callahan, 2009). Participants with scores outside the reference range (i.e., <85.36 or >126.30) were 7.2 times more likely to prematurely terminate, suggesting that role expectancies that are too high or low are associated with participants at risk of attrition (Aubuchon-Endsley & Callahan, 2009).

OCIS

The OCIS is a measure of cultural identity with orthogonal factors that have been validated for individuals with various cultural backgrounds (i.e., White American or Anglo culture, Asian or Asian American culture, Mexican American or Spanish culture, Black or African American culture, and Native American/American-Indian culture). It was utilized in this study to capture differences in White American and Native American cultural identity. Participants ranked identification with traditional cultural values with six questions for both racial categories. The OCIS has good internal consistency (reported α for subscales from 0.80-0.89, obtained α in current sample for subscales from .86–.93; Oetting & Beauvais, 1990), an established factor structure (Oetting, Swaim, & Chiarella, 1998), and good concurrent and discriminant validity within Native American samples (Venner, Wall, Lau, & Ehlers, 2006). Oetting & Beauvais (1990) found that endorsement of traditional Native American values and activities was robustly associated with the Native American subscale (r from .39–.74), but not the White American subscale (r from .18–.26).

Procedure

While individuals were completing standard intake paperwork to seek services within the clinic, they were asked to participate in a study to improve therapy services provided. Ninety percent of the clients coming into the clinic consented to participate in the current study. After completing the written informed consent form, participants were given paper-and-pencil versions of each measure. Treatment as usual was then initiated with therapists (non-random assignment) blind to the study purpose. Participants were assigned to one of the two therapists based on therapist scheduling availability. Because both providers worked overlapping hours, roughly half of presenting patients were assigned to one provider or the other. All participant questions regarding the questionnaire were directed to the principle investigator of the study, rather than therapists.

After one year, participants’ clinical files were reviewed by the primary research investigator to determine treatment outcome. Only clients who were enrolled and attended an intake followed by at least one follow-up session (ranging from weekly to monthly, depending on scheduling/availability) were examined. No additional contact was made with participants, and no follow-up measures were given. The primary research investigator reviewed the medical records and classified participants as: improved, not improved, and got worse or experienced negative side effects (as recorded in the chart by treatment providers, negative side effects may have been due to psychotherapy or psychotropic treatment initiated by psychotherapist referral). Aside from therapist judgments, the primary research investigator considered self-report symptom questionnaires (e.g., the BDI-II [Beck, Steer, & Brown, 1994] or the Beck Anxiety Inventory [BAI; Beck & Steer, 1993]) for outcome classification. These questionnaires were a standard part of assessment/treatment at the clinic, and therefore distributed during the first visit and routine follow-up visits for every participant. Efforts were made to administer these measures monthly, though on occasion completion time may have deviated because of scheduling and missed sessions.

The primary research investigator deemed participants who demonstrated a clinically significant improvement in self-report score (e.g., shift from severe to moderate depression on the BDI-II based on Beck’s categories)” and therapist-indicated improvement within the standardized therapy chart note as “improved.” Improvements included changes in diagnoses such that participants no longer met criteria for their presenting clinical concerns (e.g., a specifier of “in partial remission” or “in full remission” added to the chart). Those in the “did not improve” category showed no changes as per the therapist (e.g., were sub-threshold for improvement, but did not evidence symptom worsening or side effects) and had no clinically significant change in symptom severity. Those who were classified as “got worse or experienced negative side effects” had a note in their chart about negative side effects of treatment, and had evidenced clinically significant worsening of symptom severity on a self-report measure. Participants and data were treated in accordance with the Institutional Review Board and the Ethical Principles of Psychologists and Code of Conduct (American Psychological Association, 2002).

Data Analyses

All analyses were performed using Predictive Analytics SoftWare (PASW). To examine racial differences in expectancies (hypothesis 1) and cultural identity (hypothesis 2), t-tests were conducted to assess differences between Native American and White American participants on all scales of the PEI-R and OCIS. Chi-square tests for independence were utilized to test for racial differences in treatment outcome (hypothesis 3) and associations between therapist-participant match and treatment outcome (hypothesis 4). To examine racial differences in relations between treatment expectancies and outcome (hypothesis 5), the data set was separated by racial group. Analyses of variance (ANOVAs) were then completed for each group to examine differences in expectancies across the three treatment outcome categories.

Given the small sample size, bootstrapping was used to reexamine hypothesis 5. This statistical procedure is suggested for use with small samples when a larger sample is unattainable (Hoyle, 1999; Linden, Adams, & Roberts, 2005), and [we?] included random selection and copy of data strings by participant, which were then added to the original dataset until reaching the desired sample size (n = 1500; Good, 2000). A priori power analyses for ANOVAs revealed that a sample size of 969 was necessary with the following parameters: f = 0.10 (a conservative small effect size), α = .05, and number of groups (outcome categories) = 3. Because of repeated missing data during resampling, n = 1500 was requested from software (see df for each analysis for n). Bootstrapping was completed twice to investigate convergence of findings and overlap of variable confidence intervals with the original sample. Thus, two bootstrapped samples were created and utilized, in addition to the original sample, to examine hypothesis 5 only.

Results

Racial Differences in Expectancies, Cultural Identity, and Treatment Outcome

Native American participants had greater expectations of approval [t(18.78) = 2.17, p = .043, d = 0.86] and advice in therapy [t(30.63) = 2.07, p = .047, d = 0.54 than did White American participants (see Table 2). No racial differences were found in expectations of impressionseeking (MAI = 13.00, SDAI = 5.01, MC/WA = 12.17, SDC/WA = 4.77), audience-seeking (MAI = 16.00, SDAI = 8.20, MC/WA = 16.27, SDC/WA = 6.44), relationship-seeking (MAI = 33.42, SDAI = 10.37, MC/WA = 33.10, SDC/WA = 8.42), or PEI-R total scores (MAI = 114.33, SDAI = 24.23, MC/WA = 107.13, SDC/WA = 21.04).

| Sample | Advice expectancies | Approval expectancies | ||

| Original (n = 65) | White American Participants | Native American Participants | White American Participants | Native American Participants |

| M | 30.79 | 34.92 | 14.81 | 17.00 |

| SD | 9.48 | 5.18 | 3.59 | 3.05 |

| 95% Confidence Interval | 28.15–33.43 | 31.63–38.21 | 13.81–15.81 | 15.07–18.93 |

| First bootstrapped (n = 1298) | White American Participants | Native American Participants | White American Participants | Native American Participants |

| M | 30.56 | 35.06 | 14.87 | 17.26 |

| SD | 9.01 | 4.92 | 3.63 | 2.92 |

| 95% Confidence Interval | 30.03–31.10 | 34.46–35.66 | 14.65–15.08 | 16.90–17.62 |

| Second bootstrapped (n = 1290) | White American Participants | Native American Participants | White American Participants | Native American Participants |

| M | 30.29 | 35.28 | 14.84 | 17.11 |

| SD | 9.80 | 5.11 | 3.62 | 2.91 |

| 95% Confidence Interval | 29.71–30.87 | 34.64–35.93 | 14.62–15.05 | 16.74–17.48 |

Table 2. EXPECTANCIES DESCRIPTIVE STATISTICS IN THE ORIGINAL, BOOTSTRAPPED 1, AND BOOTSTRAPPED 2 SAMPLES

Native American participants endorsed more traditional Native American cultural values [t(63) = 2.12, p = .038, t = 0.54, MAI = 3.31, SDAI = 5.04, MC/WA = 1.08, SDC/WA = 2.86] and less White American values [t(63) = 2.51, p = .015, d = 0.70, MAI = 8.69, SDAI = 7.10, MC/WA = 13.10, SDC/WA = 5.27] than White American participants.

There were also significant associations between race and treatment outcome [Χ2(2) = 6.26, p = .044]. Native American participants largely (91%) did not improve or got worse, while 60% of White American participants did not improve or got worse. Conversely, 9% of Native American participants improved, whereas 40% of White American participants improved. Since existing literature suggests that racial matching may impact treatment outcome, a chi-square test of independence was completed to investigate whether participants who had treatment providers of the same race (Native American or White American) were more likely to prematurely terminate than participants with treatment providers of a different or mismatched race (e.g., a Native American participant with a White American therapist). Null results suggested these variables were independent.

Racial Differences in Relations between Expectancies and Treatment Outcome

Original Sample

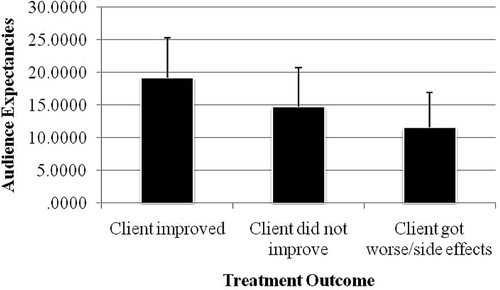

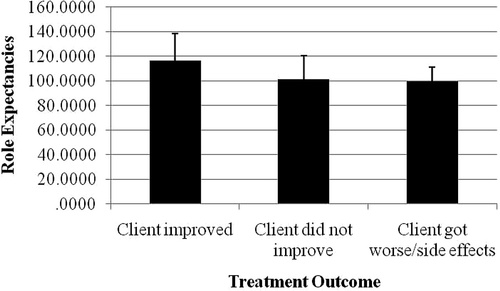

There were racial differences in relationships between therapy expectancies and outcomes. White American participants with greater expectancies of an audience in therapy [F(2,49) = 4.90, p = .011, η2 = .17] and role expectations in general [PEI-R total score; F(2,49) = 3.84, p = .028, η2 = .14] evidenced better outcome, but there were no significant relationships between outcome and expectancies in Native American participants. Follow-up contrast coefficients (see Figures 1 and 2) revealed that White American participants who improved in treatment had greater pretreatment audience-seeking expectations [contrast 1 (2, −1, −1), contrast value = 12.11, SE = 3.93, T(49) = 3.08, p = .003, d = 0.88] and role expectations [contrast 1 (2, −1, −1), contrast value = 32.34, SE = 13.07, T(49) = 2.47, p = .017, d = 0.71] than those who did not improve or whose dysfunctions got worse during treatment. No other significant results were found.

Figure 1. AUDIENCE-SEEKING EXPECTANCIES BY TREATMENT OUTCOME CATEGORY OF WHITE AMERICAN PARTICIPANTS IN ORIGINAL SAMPLE

Figure 2. ROLE EXPECTANCIES BY TREATMENT OUTCOME CATEGORY OF WHITE AMERICAN PARTICIPANTS IN ORIGINAL SAMPLE

This could be due to the small sample size of Native American participants. After resampling via bootstrapping, the new samples had confidence intervals for expectancies that overlapped with the original sample (see Table 2). Likewise, the frequency of treatment outcomes was nearly identical. In the original sample, 34% (bootstrap sample 1 = 32%, bootstrap sample 2 = 34%) of participants improved, 58% (bootstrap sample 1 = 62%, bootstrap sample 2 = 58%) did not improve, and 8% (bootstrap sample 1 = 6%, bootstrap sample 2 = 8%) got worse or experienced side effects.

Bootstrapped Sample 1

There were significant racial differences in relationships between expectations of advice and treatment outcome. White American participants who improved in treatment had greater advice expectancies than those who did not improve or those who got worse [F(2,1080) = 31.11, p < .001, η2 = .05], this was revealed via follow-up contrast coefficients [contrast 1 (2, −1, −1), contrast value = 7.78, SE = 1.32, T(1080) = 5.91, p < .001, d = 0.36]. Conversely, Native American participants who improved in treatment had lower advice expectancies than Native American participants who did not improve [t(218) = 2.73, p = .007, d = 0.37]. No significant differences were found among these two groups and the Native American participants who got worse or had negative side effects.

Bootstrapped Sample 2

We found the same pattern of results. White American participants who improved in treatment had greater advice expectancies than other groups [F(2,1091) = 29.46, p < .001, η2 = .05]; this was supported by follow-up contrast coefficients [contrast 1 (2, −1, −1), contrast value = 8.82, SE = 1.34, T(1091) = 6.56, p < .001, d = 0.40]. Conversely, Native American participants who improved in treatment had lower advice expectancies than those who did not improve [t(199) = 3.22, p = .002, d = 0.46].

This sample also revealed racial differences between expectations of approval and treatment outcome. White American participants who improved in treatment had greater approval expectancies than other groups [F(2,1091) = 9.03, p < .001, η2 = .02; contrast 1 (2, −1, −1), contrast value = 2.15, SE = 0.51; T(1091) = 4.25, p < .001, d = 0.26]. Conversely, Native American participants who improved in treatment had lower approval expectancies than those who did not improve [t(199) = 4.76, p < .001, d = 0.67].

Discussion

Race and Cultural Identity

As hypothesized, Native American participants endorsed more traditional values and customs than White American counterparts, despite historical influences on acculturation in the region. Specifically, in addition to governmental practices of Osage land acquisition and disestablishment of the Osage reservation in 1906 (Osage Nation, 2010; Romme, 2000), the Osage were also targeted for interracial marriage in the 1920s (May, 2007). This resulted in the introduction of White American culture to the area and Osage Nation and a greater prevalence of multiracial offspring. This is important to note given the influence that culture has on treatment expectancies and outcome (Bhugra, 2006).

Race, Pretreatment Expectancies, and Treatment Outcome

Native American participants expected to get more advice and approval in therapy than White American participants. This may be consistent with traditional healing practices previously received (Olson, 1999). Traditional approaches may foster indirect learning similar to advice giving, such as providing life examples, anecdotes, metaphors, and cultural beliefs rather than direct didactic learning (Olson, 1999). Traditional medicine may also include a more holistic and greater role of the healer in the client’s spirituality, community, environment, and life (Portman & Garrett, 2006), thus fostering a greater sense of approval of their lifestyle and beliefs/values than they may receive in Westernized treatments.

Greater expectations about advice and approval in treatment are important to consider since match between expectations and services received may impact treatment process and outcome (Aubuchon-Endsley & Callahan, 2007). Specifically, if role expectations are not met, it may lead to premature termination (Aubuchon-Endsley & Callahan, 2007). This is consistent with the fact that Native American participants had worse treatment outcome than White American participants.

Racial Differences in Relations Between Expectancies and Treatment Outcome

Using the original sample, White American participants with greater audience and role expectancies had better outcome. This is consistent with the previously established reference range on the PEI-R (Aubuchon-Endsley & Callahan, 2009). The average role expectancies score (107.57) for White American participants fell within the reference range and these participants experienced improvement in treatment. Although the implication from previous findings would suggest that Native American clients should have an opposite pattern of results, analyses with this sample were null. This could have been due to the small subsample of Native American participants. To test this possibility, the dataset was expanded using a resampling procedure and analyses were repeated using two bootstrapped samples. The bootstrapped samples supported similar racial differences in relations between role expectancies and outcome.

Collectively, results suggest that the high expectations (advice and approval) of Native American clients may predispose them to poorer treatment outcome. Conversely, lower expectations were related to worse treatment outcomes in White American clients. The validity of these differences is further supported by null racial differences in therapeutic and socioeconomic status variables previously associated with treatment expectancies and outcome (e.g., Clarkin & Levy, 2004; Zane et al., 2004).

Practical Implications

high role expectancies may need to be addressed with Native American clients, whereas low role expectancies may be problematic for White American clients. In addition to the development of appropriate cut scores or reference ranges with Native American clients, practitioners need to take into account race, above and beyond other socioeconomic variables, when considering how expectancies affect treatment outcome. In particular, with Native American clients who expect more advice and approval, it may be easier to adjust the therapeutic style rather than convince them that their expectancies are inconsistent with positive treatment outcome. Thus, therapists could provide more advice earlier in treatment, although the “advice” given should be evidence-based. For example, the therapist could frame an empirically-supported component of an intervention, like psychoeducation, in the form of advice. The therapist could also utilize client-centered techniques such as unconditional positive regard, genuineness, and reflective listening to instill an environment of acceptance and approval.

Regarding White American clients, whose lower expectancies were associated with worse outcome, it may be more appropriate to adjust expectancies rather than being less approving of the client or minimizing advice in treatment. This may include thorough and early treatment rationales that delineate therapeutic roles and place a greater emphasis on advice and acceptance. Overall, changing the therapy process may be more feasible with Native American clients, whereas changing client expectations may be more appropriate with White American clients. However, findings should be interpreted within the context of current study limitations.

Limitations

The sample size was moderate (n = 65), though sample size limitations can be expected when investigating rural clinics and Native American samples. Hypotheses 1 through 4 had sufficient power, and a resampling procedure was utilized to test hypothesis 5. In addition, participants were not randomly assigned to therapists. However, no participant variables (i.e., demographic characteristics and treatment expectations and outcome) were systematically related to therapist assignment. The study also utilized a relatively homogeneous sample of Native American participants. With more than 500 tribes represented in North America (U.S. Bureau of the Census, 2002), results may not generalize to all Native American clients. Nevertheless, examination of a single, historically underserved and understudied group maximizes internal validity by reducing potential sources of variability due to tribal differences.

Future Studies

Future studies could utilize the PEI-R reference range during intake procedures to screen for at-risk advice and approval expectancies. Differential interventions could then be applied depending on the client’s race. Studies could determine what type of advice would result in positive outcomes and which techniques may be best to establish a sense of approval with Native American clients. These techniques may be informed by investigating components of traditional healing practices. Future studies should also target both culturally similar tribes, to look at replicability, and culturally dissimilar tribes, to investigate generalizability of findings or tribal differences. Another important influence on treatment expectancies and outcomes that should be addressed in greater detail by future research is setting. In particular, the Native American participants in the current sample were receiving their mental health treatments in a rural outpatient mental health clinic, which may have differed greatly from the institutions where they received their primary care (e.g., Indian Health Services [IHS], local/private primary care physicians, or a larger, outpatient clinic in the closest city). Given that this care could influence what clients expect from other providers and directly or indirectly influence treatment outcome, future studies should investigate these effects. This is a factor especially for Native American clients who receive their primary care from IHS versus those receiving primary care in another setting.

(2007, September). The Milwaukee Psychotherapy Expectations Questionnaire:

(2009). The hour of departure: Predicting attrition in the training clinic. Training & Education in Professional Psychology, 3, 120–126. doi:

(1993). The Beck Anxiety Inventory Manual. San Antonio TX: The Psychiatric Corporation.Google Scholar

(1994). The Beck Depression Inventory-II Manual. London: Harcourt.Google Scholar

(2006). Severe mental illness across cultures. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica, 113 (Suppl 429), 17–23. doi:

(2001). Psychometric properties of the Psychotherapy Expectancy Inventory-Revised (PEI-R). Psychotherapy Research, 11, 69–83. doi:

(2011). Racial/ethnic matching of clients and therapists in mental health services: A meta-analytic review of preferences, perceptions, and outcomes. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 58, 537–554. doi:

(2004). The influence of client variables on psychotherapy. In M. Lambert (Ed.). Bergin and garfield’S handbook of psychotherapy and behavior change (5th ed., pp. 194–226). New York: John Wiley.Google Scholar

(2012). Predictors of treatment outcomes among depressed women with childhood sexual abuse histories. Depression & Anxiety, 29, 479–486. doi:

(2007). G*Power 3: A flexible statistical power analysis program for the social, behavioral, and biomedical sciences. Behavior Research Methods, 39, 175–191. doi:

(2005). Psychotherapy process and outcome from a racial-ethnic perspective. In R.T. Carter (Ed.), Handbook of racial-cultural psychology and counseling, Vol 1: Theory and research (pp. 256–276). Hoboken, NJ US: John Wiley & Sons Inc.Google Scholar

(2000). Permutation tests: A practical guide for resampling methods for testing hypotheses. New York: Springer-Verlag.Crossref, Google Scholar

(2007). We never was happy living like a white man: Mental health disparities and the postcolonial predicament in Native American communities. American Journal of Community Psychology, 40, 290–300. doi:

(1999). Statistical strategies for small sample research. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.Google Scholar

(2005). Evaluating disease management program effectiveness: An introduction to the bootstrap technique. Disease Management & Health Outcomes, 13, 159–167. doi:

(2000). An exploratory study of ethnicity and psychotherapy outcome among HIV-positive patients with depressive symptoms. Journal of Psychotherapy Practice & Research, 9, 226–231. Retrieved from http://jppr.psychiatryonline.org/.Google Scholar

(2007). Osage murders. Encyclopedia of Oklahoma History and Culture. Retrieved from http://digital.library.okstate.edu/encyclopedia/entries/O/OS005.html.Google Scholar

(2007). The healing path: A culture and community-derived indigenous therapy model. Psychotherapy: Theory, Research, Practice, Training, 44, 148–160. doi:

(1990). Orthogonal cultural identification theory: The cultural identification of minority adolescents. The International Journal of The Addictions, 25, 655–685. Retrieved from http://www.springer.com/public+health/journal/11469.Google Scholar

(1998). Factor structure and invariance of the Orthogonal Cultural Identification Scale among Native American and Mexican American youth. Hispanic Journal of Behavioral Sciences, 20, 131–154. doi:

(1999). Applying medical anthropology: Developing diabetes education and prevention programs in Native American cultures. American Indian Culture and Research Journal, 23, 185–203. Retrieved from http://www.books.aisc.ucla.edu/.Google Scholar

(2008). Clients’ pretreatment counseling expectations as predictors of the working alliance. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 55, 528–534. doi:

(2006). Native American healing traditions. International Journal Of Disability, Development, & Education, 53, 453–469. doi:

(2000). Osage. Retrieved May 20, 2010 from Minnesota State University-Mankato E Museum at http://www.mnsu.edu/emuseum/cultural/northamerica/osage.html.Google Scholar

(1999). Unequal treatment: Confronting racial and ethnic disparities in mental health care. Institute of Medicine. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press.Google Scholar

(2006). Testing of an orthogonal measure of cultural identification with adult Mission Indians. Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology, 12, 632–643. doi:

(2012). Race/ethnicity as a predictor of change in working alliance during cognitive behavioral therapy for intimate partner violence perpetrators. Psychotherapy, 49, 180–189. doi:

(2004). Research on psychotherapy with culturally diverse populations. In M.J. Lambert (Ed.), Bergin and Garfield’s handbook of psychotherapy and behavior change (5 th ed., pp. 767–804). New York: John Wiley & Sons, Inc.Google Scholar