Prediction of Attachment Status from Observation of a Clinical Intensive Psychotherapy Interview

Abstract

Objective: The present study addresses whether it is possible to accurately determine a subject’s Adult Attachment Interview (AAI) classification by observing a video-recorded clinical psychotherapy discussion that uses the principles of Intensive Short-Term Dynamic Psychotherapy (ISTDP).

Method: A random sample of eight of the author’s (Robert J. Nebrosky) private practice patients particpated in an AAI administered by an experienced interviewer. The authors were blind to the results of the AAI, which were scored and classified by Erik Hesse, PHD (consultant and expert in AAI coding and classification). The authors used the Adult Attachment Clinical Rating Scale (AA-CRS), which is an adapted version of the AAI “states-of-mind scales,” in conjunction with the structured ISTDP interview to obtain main classifications and subclassifications. The authors determined the pathway of unconscious anxiety according to the procedures described by Davanloo (1995, 2001) and ten Have-de Labije (2006), beginning with the structured ISTDP interview, then categorized the patient’s defenses and quality of the patient’s observing and attentive ego, discussed the clinican’s knowledge of the patient’s attachment history, and from this data drew first the major gateway of attachment using the AA-CRS. Then the authors categorized the subclassifications using the AA-CRS.

Results: The authors predicted seven out of eight AAI main classifications correctly, and five out of eight AAI subclassifications correctly, indicating that there was a statistically significant relationship between predicted and expected values for main classifications and subclassifications.

Conclusions: The authors conclude that the systematic ISTDP inquiry at the level of the stimulus (current, past, and therapeutic relationship) and response (defence, anxiety, and impulse/feeling) and combined with the clinician’s knowledge of the patient’s clinical history can effectively substitute for the AAI interview and therefore, yield an experiential reference from which to explore the patient’s state of mind using the Adult Attachment Clinical Rating Scale (AA-CRS). The authors speculate that the differences in subclassification could be accounted for by variations and/or differences in biographical knowledge obtained by the the clinician versus that of the AAI coder (Hesse).

Introduction

The Adult Attachment Interview ([AAI] George, Kaplan, & Main, 1984, 1985, 1996) and associated coding scales and classification systems (Main, Goldwyn, & Hesse, 2003) are widely regarded to be reliable standards for assessing attachment classification in adults (Cortina & Marrone, 2003; Hesse, 2008; Mikulincer & Shaver, 2007; Rholes & Simpson, 2004; Siegel & Solomon, 2003; Steele, Steele, & Murphy, 2009; Steele & Steele, 2008). While recent research studies have used the AAI with diverse clinical populations (for a review, see Steele & Steele, 2008), there have been no research studies that directly examine the relationship between AAI classifications and predictions of AAI classifications using a clinical psychotherapy interview. The present study addresses whether AAI classification can be predicted by observing a videotaped Intensive Short-Term Dynamic Psychotherapy (ISTDP) interview using the general principles of the AAI scoring and classification systems together with an adapted version of the AAI “states-of-mind” scales, and the principles of ISTDP assessment.

In a recent book, Mary Main, Erik Hesse, and Ruth Goldwyn (2008) offer an introduction to the AAI and explain that two fundamental points of emphasis (described originally by John Bowlby) must be taken into account with the AAI system of analysis: The first point is that as much as it is possible to do so, the therapist must consider actual experiences that occur in an individual’s life when looking into the origin of his or her emotional conflict. This is addressed in the AAI interview by the questions that delve directly into the speaker’s real-life experiences (called inferred experiences since historical events are altered to varying degrees in a retrospective account) and in the AAI scoring and classification systems as one of three stages of analysis (again, named inferred experiences or probable experiences). The second point of emphasis states that one must be very careful and precise about the way experiences are represented by the individual in terms of his or her state of mind. To address this issue, the interviewer administering the AAI protocol repeatedly directs the speaker’s attention to present thoughts and feelings about detailed circumstances of past events. In the AAI scoring and classification systems, the second stage of analysis consists of a systematic marking of the AAI transcript text in terms of current state of mind.

Thus, a defining feature of the AAI is its ability to measure an adult individual’s current state of mind with respect to earlier life experience (Main, 1995, 1999). To understand adult attachment classification from the perspective of the AAI is to become knowledgeable about both the form of the discourse and the content of what is remembered. Erik Hesse (2008) explains “a speaker’s discourse in the AAI is judged to be coherent when he or she appears to be able to access and evaluate memories while simultaneously remaining plausible (consistent or implicitly truthful) and collaborative” (p. 566). Secure adult attachment may be taken along these lines to incorporate

episodic memory (remembering factual details of the past such as names, dates, places, people, objects, events, etc);

semantic memory (the meaning attributed to early life events);

autonoetic memory (autobiographical self-knowing termed “autonoesis” by Wheeler, Stuss, & Tulving (1997) whereby the speaker has an active awareness of self through the course of time);

working memory (the ability to actively think about early life events while at the same time remaining consistent, coherent, and collaborative); and

implicit memory (also referred to as procedural memory, which refers to the habits, routines, skills, inclinations, tendencies, and associations of feelings or moods which operate outside of conscious awareness)

(See Main, 1998, for a discussion of this topic.)

The degree of coherence of the AAI transcript is determined by the way in which the parts are internally consistent and clearly related, form a logical whole, or are adapted to context (Main & Goldwyn, 1998).

Hesse (2008) stated “the eventual assignment to an overall state of mind with respect to attachment will have no further dependence on the speaker’s probable experiences with the parents during childhood” (p. 564). The precision with which inferred experience is obtained in the AAI can thus be said to be a vehicle for evoking the type of visceral response that reveals the speaker’s implicit state of mind. As George, Kaplan, and Main (1996) describe, the AAI can “surprise the unconscious” with a focus on memory systems and narrative quality (p. 3). In this sense, what is being measured in the AAI is not a fixed representation of earlier life experiences, the way the internal working model has implied (i.e., symbolic meanings, such as self-as-rescuer or self-as-victim, which denote versions of episodic memory), but evolving or changeable states of orientation to attachment experiences that have been shaped over time. In the AAI this orienting response is measured directly by the “states of mind scales,” which are behavioral and linguistic indices of implicit memory, recording patterns of speech, logical fluency, behavioral tendencies, or habitual statements that reveal underlying attitudes about attachment-related experiences. The state of mind, with respect to attachment, is the orienting of the self in the context of telling one’s story, remembering the factual details, actively remembering, or placing one’s self in one’s mind at one point in time (sitting across from the interviewer during the AAI interview, etc.).

Intensive Short-Term Dynamic Psychotherapy (ISTDP) is an evidence-based psychotherapeutic technique that, we propose, has an underlying structure similar to the AAI and evolved from the same underlying principles. Habib Davanloo (1978, 1980), like Bowlby (1969), concluded that psychoneurosis was caused by rupture of the secure attachment bond between parent and child. David Malan (1979) emphasized the importance of accurately recounted experience (as represented in the “triangle of persons”) and precise labeling of state of mind (as represented in the “triangle of conflict”). From an ISTDP clinician’s perspective insecure states of mind (or more broadly defined, psychopathology) result from fearful avoidance of painful feelings through defensive processes (minimization, vagueness, ignoring, repression, projection, dissociation, acting out, etc.) and create anxiety (striated, sympathetic, parasympathetic, and cognitive-perceptual). The clinician assesses how long and to what degree implicit feelings and impulses are likely to have remained outside of conscious awareness. The deeply internalized feelings and impulses express themselves psychologically, and, to various degrees, somatically and/or behaviorally; in the mind of the patient it is as if the events of the past continue to occur. This is why states of mind must not be regarded as fixed representations but as evolving or changeable states. They constitute an active stance toward the world.

The task of the ISTDP therapist is, thus, to create a therapeutic narrative that interdigitates with semantic, autobiographical, and procedural memory, allowing the patient to generate earned secure attachments. To do this, the patient must fully experience his or her emotion with a loving attentive ego1 and healthy superego in the presence of the therapist. As explained by Josette ten Have-de Labije (2010),

. . .to achieve healthy emotion regulation, the patient must be able to: detect eliciting essential stimuli from the external or internal world (current situations and persons), to analyze them and to interpret the information in the context of earlier experience (past, transference) in order to estimate the meaning of the eliciting stimuli; to detect, analyze, and interpret the physiological manifestations of that particular emotion and to give these the correct emotional label; to know the cognitive contents of that feeling and to give adequate words to what the feeling is about; to be aware of proprioceptive stimuli and the action tendency; to establish the causal link with the preceding essential stimuli; and to detect, analyze, and interpret whether and how the patient express his feelings and whether he is herewith fulfilling what he really wants (p 87).

By means of a therapeutic intervention incorporating these elements, the ISTDP therapist determines the degree to which the patient is capable of acting in an attentive, observing, and caring manner towards him- or her-self. Thus from the perspective of assessment the ISTDP therapist determines the nature of the pathology (how long and to what degree implicit feelings and impulses have remained outside conscious awareness), and from the perspective of intervention the therapist determines the patient’s adaptive potential (derepression of unconscious feelings and impulses).

Whereas the AAI analyzes linguistic dysfluencies and behaviors to assess the state of mind of the speaker, the ISTDP approach (in conjunction with an adapted version of the AAI “states of mind” scales) has the added benefit of being able to utilize defense structure, physiological symptoms, action tendency2, emotion regulation, and personal knowledge of the patient’s past as added means to assess state of mind with respect to attachment. The structure of the ISTDP approach to analysis is similar to that of the AAI in that state of mind is determined in the context of specific attention to experience in the past, present life, and feelings towards the therapist. The inquiry at the level of the stimulus is designed to activate an implicit memory response much in the same way the AAI can “surprise the unconscious.” When an implicit memory response is activated, the clinician may then begin a dynamic assessment of the attachment states of mind. The authors hypothesize that the systematic ISTDP inquiry at the level of the stimulus (current, past, and therapeutic relationship) and response (defense, anxiety, and impulse/feeling), combined with the clinician’s knowledge of the patient’s clinical history will effectively substitute for the AAI interview and, therefore, yield an experiential reference from which to explore the patient’s state of mind using the Adult Attachment Clinical Rating Scale (AA-CRS). Additionally the authors expect that clinically relevant information yielded from the ISTDP interview, such as defense structure, physiological symptoms, action tendency, and emotion regulation will enhance the overall precision of the AAI predictions and provide important descriptive information.

Method

Sample

Twelve individual patients agreed to participate in the study; 4 interviews were omitted. The omissions were due to faulty recordings of the AAI Interview and are assumed to be random. The sample consisted of eight individual patients (N=8), recruited from the author’s private practice in Del Mar, California. In accordance with recent research on the effectiveness of ISTDP with personality disorders (Messer & Abbass, 2010; Abbass, Sheldon, Gyra, & Kalpin, 2008; Town, Abbass, & Hardy, 2011), neurotic disorders (Abbass & Driessen, 2010; Abbass, Hancock, Henderson, & Kisely, 2007; Abbass, Town, & Driessen, 2011; Driessen, Cuijpers, C. M. de Maat, Abbass, Jonghe, & Dekker, 2010; Neborsky & Lewis, 2011; ten Have-de Labije, 2006; Trujillo, 2006) and somatoform disorders (Abbass, Kisely, & Kroenke, 2009), the authors selected individuals for this study with DSM-IV diagnoses of Major Depressive Disorder, Dysthymia, Panic Disorder, Generalized Anxiety Disorder, Bipolar Disorder without Psychotic Features, Dependent Personality Disorder, Borderline Personality Disorder, Histrionic Personality Disorder, and somatization as a prominent pathological defense structure.

Measures

Adult Attachment Interview (AAI)

George, Kaplan, & Main, 1984, 1985, 1996 The AAI is a measure designed to assess an individual’s current state of mind with respect to attachment experiences while growing up. This is a semistructured clinical interview consisting of 18 questions. Questions are asked in a set order with room for follow-up questions to probe for more detailed answers as needed. The interview is designed in such a way as to point out inconsistencies in life history. Subjects are asked to give five adjectives to describe their relationships with parents and then to provide concrete examples to support each of the five adjectives. Responses in support of the concrete examples are considered together with the adjectives to see if there are any discrepancies or contradictions. The interview as a whole requires precise attention to linguistic form (i.e., dysfluencies, mistakes on the part of the subject, hesitations, odd usage of words and phrases) and, therefore, the interview is recorded and transcribed verbatim including all errors and dysfluencies. No references are made to nonverbal or pragmatic features of the subject’s responses.

Analysis of the AAI proceeds in three stages with one additional review stage. The first stage is referred to as inferred experience and all information relevant to probable experiences with each attachment figure during childhood is noted. There are five total experience scales and each scale is graded according to a 9-point format with a lower number for least consistent between the experiences and higher number for most consistent. The second phase is referred to as current state of mind, during which the speaker’s apparent current state of mind, rather than reported attachment history, is noted. In this assessment stage there are three scales associated with secure states (coherence of transcript, metacognitive monitoring, and coherence of mind), four scales associated with dismissing states (idealization, insistence on lack of memory, derogating dismissal of attachment, and fear of loss of the child through death), two scales associated with preoccupied states (involving/preoccupying anger and passivity/vagueness in discourse), and two scales associated with disorganized states (disorganized [Ud] states of mind with respect to loss and Ud states of mind with respect to abuse). Each scale is graded according to a 9-point format (typically, this format will be represented as 1) none, 3) slight, 5) moderate, 7) marked, and 9) extreme). There are additional criteria for each main classification that do not fall into the formal scales, and these are used when making a final determination as to the “main gate” classification. However, these additional criteria are not required in order to assign a main classification in a particular category. The main classifications are assigned at this point for organized states of mind (secure, dismissing, and preoccupied).

The third phase consists of bottom-up and top-down approaches to assign classifications based on inferred experience and state of mind, respectively. Once the experience scales and states of mind scales have been determined, this phase involves making comparisons between the results obtained. On the one hand, there will be the expected classifications derived from the experience scales, and on the other hand there will be the classifications from the states of mind scales. This step helps to ensure the internal consistency of the classification process.

Finally, when phases 1 through 3 have been completed, a fourth phase involves using a series of checklists and marking a summary form to denote final classification. Subclassifications are made at this time, and additional placements into the disorganized and cannot classify categories are made. While there are no formal scales associated with the cannot classify category, there are specific indications for when and how to assign this classification. Adam, Gunnar, and Tanaka (2004, p. 110) referenced Main and Goldywn “Adults are classified either secure/autonomous (F), insecure/dismissing (Ds), or insecure/preoccupied (E). They may also be classified unresolved/disorganized (U) with respect to trauma or loss (Main & Goldwyn, 1994).”

Adult Attachment Clinical Rating Scale (AA-CRS)

Bundy, 2009 The first phase of assessment is structured identically to the main gate classifications on the AAI except that it is put into a checklist-type format with descriptions of criteria omitted for ease of use. Criteria are scaled and graded in a 9-point format identical to the format of the AAI. Classifications are made for organized states of mind (secure, dismissing, and preoccupied), disorganized states of mind, and cannot classify. The second phase of assessment consists of the AAI subclassifications written, again, into a checklist-type format with lengthy descriptions omitted. For the purposes of this study, the authors assume prior knowledge of the AAI scoring and classification systems. Additionally the authors used the AAI scoring and classification systems manual for reference particularly when assigning subclassifications. The rating scale is used for purposes of consolidating information into an easy-to-use format. Experience scales are omitted because the ISTDP interview format is structured in a significantly different way and has a different method of analyzing specific life events, circumstances, and experiences. Whereas in the AAI inquiries about experiences as a child are in a preset format with additional probes clarifying information in certain areas, the ISTDP interview is a dynamic assessment integrating past and current experience and behavioral observations in the therapeutic transference with observed intrapsychic phenomena in the moment-to-moment interactions between patient and therapist. While the ISTDP clinical interview may tap into the kinds of experiences assessed in the AAI, it is viewed as an adjunct to the dynamic assessment (in the AAI the specific details about what happened are recorded verbatim and probed minimally). While one advantage of the AAI is its attention to descriptive narrative and linguistic coherence, an advantage of using the AA-CRS is the additional relevant information, such as defense structures and physiological manifestations, available for review.

Procedures

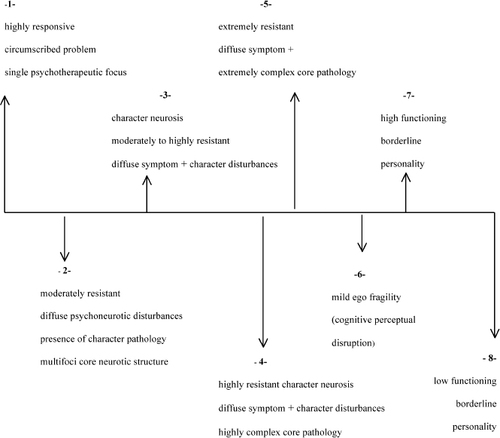

Participants’ informed consent was obtained and the study was conducted under the auspices of the Institutional Review Board (IRB) of UCSD School of medicine. Eight of the author’s private practice clients participated in the AAI interview, which was administered by Kelly Abrams, Ph.D. The AAI transcriptions were completed by Jillian Boldway. The interview transcripts were scored and classified independently by Erik Hesse, Ph.D. The authors reviewed selected videotapes of clinical ISTDP interviews that were conducted at the approximate time of the AAI interviews. The authors reviewed each case blind to the results of the AAI. Beginning with the video-recorded structured ISDTP interview, the authors determined the pathway of unconscious anxiety according to the procedures described by Davanloo (1995, 2001) and Have-de Labije ten (2006), categorized the patient’s defenses and quality of the patient’s observing and attentive ego, assessed the degree of pathological severity guided by Davanloo’s spectrum of psychoneurosis (see Figure 1), and discussed the clinican’s knowledge of the patient’s attachment history. Throughout this process the authors paid close attention to the videotapes to observe the occurrence of the types of behaviors and linguistic dysfluencies that are characteristic to each main gate classification on the AA-CRS. Behaviors and linguistic dysfluencies were recorded using the AA-CRS, and from this data the authors drew first the major gateway of attachment using the AA-CRS. The authors then proceeded to the second phase of assessment which consisted of further discussion and review of videotapes to determine subclassifications according to the AA-CRS.

Figure 1. THE SPECTRUM OF PSYCHONEUROTIC DISORDERS (ADAPTED FROM DAVANLOO, 1995).

Statistical Analyses

A Mann-Whitney U test was carried out to evaluate the hypothesis that predicted AAI categories related to actual AAI classifications. The test showed a nonsignificant difference between predicted AAI category and AAI classifications, U = 28.00, p = .32, indicating that the predicted and actual AAI main classification scores were not significantly different and are therefore related. A second Mann-Whitney U test was conducted in a similar manner for the subclassifications to evaluate the hypothesis that predicted AAI sub-categories related to AAI subclassifications. Again, the test showed there was a nonsignificant difference between predicted AAI subclassification scores and actual AAI subclassifications, U = 20.00, p = .06, thus indicating that the predicted and actual subclassification scores were not significantly different and are, therefore, related. These results suggest that there is not a significant difference between AAI predictions and AAI classifications for both the main and subclassifications.

Results

Case Number One

The patient is a 21 year-old male college student. He is the older of two siblings. He presented with symptoms of panic attacks, which had begun more than three months prior to the interview and which had been unresponsive to SSRI medications. The patient came from an intact family with supportive and loving parents. The one psychotrauma in his history involved the death of his beloved uncle (his mother’s brother) from human immunodeficiency virus. The patient’s mother suffered greatly from grief after her brother’s death, and her depression affected the patient. He developed symptoms of severe anxiety upon the possibility of sexual intimacy in relationships. The patient was diagnosed with unresolved loss both for his grief and secondarily to his mother’s bereavement.

Predicted Category Placement Indices for unresolved/disorganized attachment observed during the clinical interview were: disorganization with respect to time (referencing different times when loss occurred), prolonged silences, unfinished sentences, and eulogistic speech. His defenses were seen as organized against vulnerability (perfectionism, repression, defiance, instant repression [empty head], humor; he would ignore or smile in response to the therapist’s interventions. He projected his fear about the loss of his uncle onto his mother and others (not wanting to “conjure up” negative feelings in the other). Anxiety manifestations observed were striated muscle tension (head to toe), sympathetic reactions (hypervigilance, increased heart rate, shallow breathing), and some mild parasympathetic reactions (stomach aches). This patient was diagnosed with panic disorder without agoraphobia. The position on Davanloo’s Spectrum of Psychoneurotic Disorders was 3.

On the whole this individual exhibited signs of secure-autonomous state of mind (good observing ego with correct labeling of anxiety and some instances of metacognitive monitoring), though he exhibited some signs of a dismissing state of mind (idealization of the father, restricted in feeling, and insistence of a lack of memory at moments when confronted with sadness). The main classification was assigned to unresolved/disorganized with respect to the loss of his uncle, with emergent properties of secure-autonomous state of mind, and some instances of dismissing state of mind (U/F/Ds). It should be noted here that subclassifications were not assigned for this case due to the authors’ initial attempts to work out a system of analysis that would capture the main classification only (once the authors became comfortable with the system of analysis for the first case, subclassifications were assigned for the remaining cases).

Assessed Character Assignment In Erik Hesse’s analysis, the main category U/d was likewise for the loss of the uncle due to lapses in reasoning (confusion surrounding the loss). The secondary placement of Cannot Classify (CC) was because a single strategy did not seem to prevail. (While Dr. Hesse considered the text to be globally closest to secure (F), there were too many examples of D-like instances of expressions of strength, normalcy, and “not caring” for the AAI transcript on the whole to be considered secure; likewise there were too many topics and responses in the AAI transcript that were unexplained.)

In this first case the authors attempted to analyze via the clinical interview, the CC classification should have been made following the U/d classification for the same reason noted by Dr. Hesse—a single strategy did not seem to predominate. The reason for this omission was simple error on the part of the authors while working out a method of analysis using the AA-CRS. The final classification, including subclassifications, rendered by Dr. Hesse was U/CC/F2/F4/Ds3.

Case Number Two

The patient is a 60-year-old retired male engineer suffering from panic disorder, agoraphobia, hypochondria, and atypical depression. He had Hodgkin’s disease when he was in his 40s and his heart valve had been damaged by radiation treatment. The patient became anxious when considering the possibility that he might need a heart valve replacement at some future time. He became progressively more housebound and more hypochondrical, with unrealistic fears of physical activity. He was clingingly link-dependent on his wife for safety. As a child he was favored by his mother as “the golden child,” and he transferred this dependency from his mother onto his wife.

Predicted Category Placement Indices observed for Preoccupied (E) category placement during the video-recorded clinical interview were: passive/vague discourse (implicit sense of failure, repetitious small complaints, and inchoate representations of implicit negative experiences), identity tied to fearful experiences, self-blame, and uncertainty about the past. On the whole, this individual projected his own fears of inadequacy onto others (unable to tolerate rejection due to poor self-esteem and preconceived ideas about others). Defenses observed in the clinical interview were passivity, compliance with the therapist, dependency, vagueness, projection, somatization, and withdrawal. Anxiety manifestations were noted in the striated muscles, smooth muscles (sympathetic nervous system), and in various reported physical illnesses. The DSM-IV diagnoses included panic disorder with agoraphobia, depressive disorder NOS, and dependent personality traits. Position on Davanloo’s Spectrum of Psychoneurotic Disorders: 4.

The main classification was assigned to E and the subclassification to E1 because the defining characteristic of this individual was that his identity was closely tied to early experiences with others (dependency with mother transferred to wife and dependent traits observed in relationship to the therapist). On the whole the individual appeared to be passive, compliant, and preoccupied with the past and with others’ perceptions of him (main features of E1 subclassification).

Assessed Character Assignment Dr. Hesse observed in his analysis that this individual was identified by characteristics typical of the E1 classification. He also observed that the individual exhibited a kind of “chronic mourning” about having grown up in childhood with a mother who had a serious illness. For this reason, Dr. Hesse assigned an additional secondary classification of Cannot Classify (CC) since the inchoate representations of implied negative experiences exhibited by this person may have been different than what is typical of most speakers falling in this category (which is why the “flavor” of the discourse violations appeared to differ from a classic E1 text). These instances of chronic mourning appeared in the loss section of the AAI, but did not fit into the unresolved/disorganized (U/d) scoring system. The final classification that was assigned by Dr. Hesse: E1/CC.

Case Number Three

The patient is a 51-year-old female who works as an executive assistant and who has suffered panic attacks during the preceding six months. The panic attacks were precipitated by an intimate relationship with a co-worker who, she reported, was immature and acted out sexually with pornography and strippers. She felt she could not be safe in the relationship with this partner, but was unable to leave it.

The patient is one of two siblings—a female fraternal twin. History is significant for early childhood abandonment trauma. When the patient was six years old her parents divorced because her mother had been unfaithful in the marriage. Upon discovering the affair, the patient’s father divided the siblings; he kept the sister with him and gave custody of the patient to her mother. The patient and her mother were homeless for two years after the divorce.

Predicted Category Placement Indices for placement in the preoccupied (E) category observed during the clinical interview were: linguistic confusion/slips; unbalanced blame towards self/others (including excessive guilt); identity tied to others (perceived things as a rejection); involving/preoccupying anger, and strikingly uncertainty and indecisiveness. Defenses included projection, projective identification (therapist as perpetrator), and acting out. This individual exhibited a regressed ego with a highly punitive superego with self and other. Anxiety manifestations included striated muscle tension and sympathetic nervous system activation (including frequent panic attacks). The patient had been diagnosed with panic disorder without agoraphobia, and she exhibited borderline personality traits. The position on Davanloo’s Spectrum of Psychoneurotic Disorders: 4.

A defining characteristic of the interview included preoccupied fear associated with early childhood trauma The patient would have been assigned an E3a classification on the AAI were it not for the patient’s responsiveness to therapist’s interventions over the course of the interview; F4b was the best-fitting alternative classification that allowed for both E3a traits and the earned secure attachment signified by the patient’s responsiveness. The E3 transcripts differ from E1 (passive) and E2 (preoccupied anger) in that the central theme relates to fearful preoccupation about traumatic events. The E3-type individual typically is seen to be confused, fearful, and overwhelmed—it is interesting to note that this category has been found to be associated with borderline diagnoses (Hesse, 1999). In this example, an E3a category placement, the preoccupying fear was conceptualized in terms of frantic unconscious efforts to avoid internalized feelings of abandonment. The F4b is the best fitting alternative classification, signifying a move toward earned secure attachment (during the clinical interview this individual was responsive to therapeutic interventions designed to undo unconscious projections).

Assessed Character Assignment The AAI classification for this patient notes considerable trauma and chaos (witness to marital violence, sporadic outbursts of rage, victim of sexual abuse, and attempted rape). The secure (F) category placement for the main classification was assigned because the patient did not lapse in any notable way during the AAI interview when discussing her traumatic experiences. Dr. Hesse qualified this rationale for classification with his determination that “at some higher level, rejection and neglect must have occurred.” Thus one explanation for the difference between AAI prediction and AAI classification for this case (i.e., the fact that AAI prediction was based on preoccupation regarding childhood abandonment specifically and AAI classification was based on an ultimately rational overview with respect to other traumatic experiences) can be accounted for by superior biographical data on the part of the author (RJN). Final AAI classification F5/F4a/(other) acknowledges moderate preoccupation with relationships to attachment figures with acceptance of continuing involvement.

Case Number Four

The patient is a 51-year-old male executive who came to therapy because he was in an unhappy love relationship and felt conflicted about leaving his partner. His underlying trauma was deep guilt over an episode of violent acting out (shooting a gun) at his brother in his teenage years. The patient suffered from unresolved sibling rivalry between himself and his brother for his father’s affection. Indices of Secure (F) attachment classification were: linguistic coherence, metacognitive monitoring, coherence of mind, flexibility/adaptability during the interview process, and valuing of attachment.

Defenses included intellectualization, repression, and projective identification (identifying the therapist as the dismissive father figure). Anxiety manifestations occurred in the striated muscles and sympathetic nervous system. DSM-IV diagnoses: Dysthymia, Bereavement, and Partner Relational Problem. Position on Davanloo’s Spectrum of Psychoneurotic Disorders: 3.

Predicted Category Placement The F1 subclassification rationale: patient articulated some harsh childhood experiences that included moderate rejection of attachment; however, his state of mind (guilt over the episode with the gun, which created a need for punitive and avoidant/dismissive self-structures) did not prevent him from utilizing the therapy successfully (therapist was able to undo the projection and the patient made a breakthrough to unconscious feeling/impulse during the clinical interview).

Assessed Character Assignment Analysis of the AAI transcript indicated this case to be a fairly straightforward secure (F) transcript in general due to the following reasons: (a) no active indices of preoccupied anger; (b) relevance violations were not passive/vague; (c) no idealization of either parent; (d) no notable claims to lack of memory; (e) no derogation of attachment figures; and (f) no globally anomalous violations of coherence that could lead to a CC classification. The F1 subclassification was determined based on speaker’s articulation of a harsh childhood while maintaining a “cold” (setting aside) and “lead with your chin” stance about attachment-related experiences and an ongoing collaborative stance during the interview. F1 transcripts in general most closely resemble Dismissive (Ds) insecure attachment, which is why it was important in this case to rule out Ds category descriptors. Final classification determined by Dr. Hesse’s analysis of the AAI: F1

Case Number Five

The patient is a 48-year-old geologist (on disability at the time of testing) who is seeking therapy as an alternative to electric cortical shock therapy for severe bipolar depressive episodes. She has suffered from bipolar disorder since her early 20s and has had manic as well as depressive episodes. She also has had systemic lupus erythematosus for 10 years, which complicates her bipolar disorder. She is an only child whose mother was quite histrionic and narcissistic. The patient suffered from significant guilt because of her anger at her mother’s unavailability. She also developed a highly sexualized attachment to her father, for which she also felt guilt.

Predicted Category Placement Indices of Secure (F) attachment were: adaptive response to the therapist’s interventions in the clinical interview (derepression of the unconscious, de-activation of the punitive superego structure, and re-orienting of the observing ego), yielding high scores for autonomy, flexibility, and collaboration with the interview process.

Pathological defense structures included: instant repression (ignoring and minimization), projection, and somatization. Manifestations of anxiety included: striated muscle, smooth muscle (sympathetic nervous system activation), and cognitive-perceptual disruption (dissociation). DSM-IV diagnoses included: Bipolar I Disorder, Most Recent Episode Mixed; and Histrionic Personality Disorder. Position on Davanloo’s Spectrum of Psychoneurotic Disorders: 4. The F4b subclassification was determined on the basis that this individual exhibited ongoing pre-occupation about childhood experiences with parents (controlling father and role-reversing with mother), however the patient ultimately collaborated and responded adaptively to therapist’s interventions. Final AAI prediction: F/F4b

Assessed Character Assignment AAI transcript analysis likewise yielded F/F4b category placement for the following reasons: (a) some preoccupation with attachment-related experiences evidenced by excessively long turns of speech, occasional violations of relevance (i.e., discussing the father when the topic is the mother), and passive/vague discourse; (b) speaker reported experiencing a generally difficult childhood and adulthood with mental health problems in addition to medical condition (systemic lupus and chronic pain); (c) speaker reported experiences with parents on the whole described as unloving; (d) at times the speaker gave the impression of being vague and detached; and (e) the greater part of the interview was determined to be “ultimately rational and convincingly conscious.” Final AAI classification: F/F4b

Case Number Eight

The patient is a 40-year-old female yoga instructor who was in a conflicted marital relationship and experienced anxiety, depression, sexual acting out, and financial irresponsibility. The patient had suffered severe early childhood trauma: her mother succumbed to a deteriorating schizophrenic illness and had to be involuntarily hospitalized when the patient was six years old. The patient is the youngest of five siblings and closely attached to her older sister. Both the sisters were placed in an orphanage upon the mother’s hospitalization. At the orphanage, they were separated in different wards. The father raised the remaining older three male siblings. When the patient reached adolescence she was placed in foster care.

This patient was assigned the Cannot Classify (CC) because there were emergent secure (F) properties in the interview that reflected a shifting state of mind with respect to attachment experiences. In this case preoccupied (E) seemed like the closest, best-fitting alternative to CC classification due to the following characteristics of the interview: role-reversal (accommodations to the psychic needs of the other together with inattention toward the self); inchoate representations of negative experiences (resisting mental coherence at the level of the stimulus, using tactical defenses to keep new information or the therapist at bay, and splitting and dissociation defenses); fearful preoccupation about past traumatic events (E3), which was evidenced by an inability to shift attention away from traumatic events (for example, she would shift attention away from a discussion of feelings in favor of the relational strategy of “going dead” in response to situations or people perceived as threatening); poor boundaries between self and other; and an inability to tolerate separations from others. Secure (F) indices included responsiveness to therapeutic interventions and some metacognitive monitoring.

Pathological defense structures included: ignoring, neglecting, splitting (to overcome anxiety, the other is “made into” a very bad person), denial and dissociation (avoidance of underlying anger). Anxiety manifestations included: striated muscle tension and cognitive-perceptual anxiety discharge. The DSM-IV diagnoses included: anxiety disorder NOS, dysthymic disorder, and borderline personality disorder. Position on Davanloo’s Spectrum of Psychoneurotic Disorders: 6.

Predicted Category Placement The authors assigned this individual an E3 subclassification due to the central characteristic of the interview—a whole being preoccupied fear, overwhelmed, and confused, rather than angry (E2) or vague (E1). It is an interesting to note again that the E3 subcategory has been found to be associated with borderline diagnoses (Hesse, 1999). The F4b as an alternative subclassification was assigned because of ongoing confusion and fearful preoccupation with traumatic experiences and some valuing of attachment (responsiveness to therapeutic interventions and metacognition).

Assessed Character Assignment The AAI transcript analysis yielded CC/E3/F4b classification because “the speaker’s mind remains traumatized by fear, but the effects have been altered (for the better) by therapy. . .in the end what the reader comes away with is an impression of a speaker who, while having come a long way, is still overwhelmed by frightening experiences related to attachment” (included in erik hesse’s notes along with final aai classifications). In summary, the text as a whole resembled an E3 classification with evidence of progress made toward earned secure attachment (forgiveness of parents, humor, recognition of the effects of experiences on the shaping of the self, and valuing of attachment). The AAI analysis also identified some characteristics common to Ds3 profiles in that the speaker attempted at times to down play the extreme nature of parenting experiences. This characteristic, however, was not pronounced enough to assign Ds3 to the final classification.

Case Number Nine

Patient is a 50-year-old female psychotherapist. She suffered from anxiety and depression along with extremely low self-esteem. She was in an abusive marriage and felt helpless to leave the relationship because of guilt about separating her son from his father. Secondary to her inability to leave the marriage was her perceive stigma of being a divorcee. The patient is the younger sister of two siblings. She grew up in a trailer park in a working-class environment with parents who were socially neglectful. Her mother was obese and poorly educated and her father was the “black sheep” of the family. The patient felt excessive shame as a child about her parents’ neglectful behaviour and low social stature. She expressed guilt about having these feelings towards them. She was also traumatized as the victim of a violent assault, having been stabbed randomly by an out-of-control psychiatric patient.

Predicted Category Placement This individual was seen to fit the CC classification during the video-recorded clinical interview because indices characteristic of two preoccupied profiles (E1 and E2) were present enough to make it difficult to assign one single classification. Indices common to E profiles included: excessive blame toward self, involving/preoccupying anger, identity tied to parents and early trauma, inchoate representations of negative experiences, implicit sense of personal failure, ambivalence between involving/preoccupying anger (E2) on the one hand and passivity (E1) on the other, and evaluatory oscillations (compliance on the one hand and defiance on the other—recognizing abusive domestic relationship at times and at other times defending the relationship). Indices of secure (F) classification included some metacognitive monitoring (responsiveness to therapeutic interventions), including rueful recognition of the power of the past in shaping self.

Defenses exhibited in the clinical interview included: denial, projection, obsessions, compliance/defiance, primitive identification with the victim parent (her mother), helplessness, and relentless self-attack. Manifestations of anxiety included striated muscle tension, and cognitive-perceptual discharge (some lapses in consciousness that would interrupt the progression of the narrative (evidenced by repeated ambivalence and turning back to masochistic position with respect to sadistic domestic partner). The DSM-IV diagnoses included: depressive disorder NOS and dependent personality disorder with masochistic features. Position on Davanloo’s Spectrum of Psychoneurotic Disorders: 6.

The E1 and E2 subclassification was determined for this case since one of the defining features of the clinical interview was the patient’s ambivalence between involving/preoccupying anger on the one hand (E2) and passive/helpless dialogue on the other. The F4b alternative subclassification was determined because there were emergent F properties within the interview as evidenced by the patient’s ability to sometimes monitor her own thoughts and respond adaptively to therapeutic interventions.

Assessed Character Assignment The AAI analysis indicated that this individual has the following characteristics of preoccupied (E) profiles: passivity of thought process, identity closely tied to parents, uncertain/indecisive/unobjective speaking, extensive jargon use, and psychological expressions (inappropriately clinical references, which were seen to be unrelated to an authentically reflective state of mind). Indices of a secure (F) transcript were: flexibility, valuing of attachment at times, forgiveness and compassion towards mother, and a lively personal identity. In terms of subclassification for this case, Dr. Hesse indicated that on the whole the transcription contained aspects of E1, E2, and F4b that were mixed together making the text Cannot Classify. It is interesting to note in this case that there was a positive outcome to the therapy in that the woman eventually divorced her abusive husband and married a man with whom she developed a loving and successful relationship. This result of therapy can be seen to be reflective of emergent F properties (signifying adaptive potential).

Case Number Eleven

The patient is a 61-year-old male who works part-time as a psychotherapist, part-time as a construction worker and who has a history of lifelong anxiety with secondary depression. He is a former heroin user who was addicted for more than 20 years (a large part of that time was spent homeless). The patient has an older brother. During childhood, and over the course of his life, he had been perceived as sensitive and artistic. This resulted in a great deal of conflict with his mother, who he reports as being cold, authoritarian, harsh, judgmental, and controlling. He reports experiencing symptoms of psycho trauma when he was removed from his first school (where he was happy, well adjusted), and placed in a regimented private school (where he did not fit in). At the time the patient presented for therapy, he was in a romantic relationship with a partner who he described as rigid and controlling. He was suffering panic about his aggressive feelings in that relationship.

Predicted Category Placement Indices of U/d disorganized classification during the video-recorded clinical interview included: lapses in the monitoring of reasoning, disoriented speech, prolonged silences, and dissociation. Cannot Classify (CC) was assigned as a secondary placement because both Dismissing (Ds) and Preoccupied (E) features were present during the clinical interview. Neither was considered to be predominant. Indices of D category placement included: ongoing detachment and dismissal as a defense against emotional closeness, insistence on lack of memory, little articulation of hurt or distress, minimization of negative experiences, and abstract/remote from memories and feelings. Indices of E main classification were: identity tied to parents, and involving/preoccupying anger.

Pathological defenses employed by the patient included: minimization, projection, detachment, humor, sarcasm, identification with the aggressor (in this case the aggressor was his mother who would shut him down if he exhibited even a minimal amount of defiance toward her rigidly set rules), dissociation and slouching. Anxiety manifestations included: striated muscle tension, parasympathetic discharge (numbness/shut down and dizziness), and cognitive-perceptual discharge (incoherent process and dissociation). The DSM-IV diagnoses included: panic disorder without agoraphobia, dysthymic disorder, and personality disorder with dependent traits. Position on Davanloo’s Spectrum of Psychoneurotic Disorders: 7.

The Ds1 subclassification was concluded based on the patient’s dismissal of most attachment-related considerations from thinking. The Ds4 subclassification was considered for this individual because the patient exhibited marked fear regarding the loss of his child through death; however, Ds4 subclassification was ruled-out due to the fact that in this case the fear could be traced to its source (the patient’s son was being stalked by gang members). In order to assign The Ds4 subclassification, the fear surrounding the loss of the child through death must be connected to an unknown source. The E2 subclassification was assigned based on this patient’s frequent underlying expressions of anger towards his mother during the clinical interview.

Assessed Character Assignment AAI analysis for this case yielded a main-classification assignment of U/d due to extreme behavioral responses related to traumatic losses of two girlfriends. The CC was added as an alternative main category placement due to there being passages in the transcript that were representative of both dismissing (Ds) and preoccupied (E) placement. Dr. Hesse assigned the subclassification Ds4 because in his assessment “there is fear of loss of imagined child which is not traced to its source.” In this case, as noted above, the authors were able to trace the fear of loss of death of the child to its source, leading to a Ds1 assignment. The AAI analysis indicated that the transcript on the whole was “E-like” with some notable instances of involving/preoccupying anger (E2). Final classification: U/CC/Ds4/E-general.

Discussion

The purpose of this study was to discern whether it would be possible to accurately predict AAI classification based on observations of a clinical psychotherapy interview. In seven out of the eight cases for this initial pilot study, main classifications were predicted correctly. For the subclassifications five out of eight cases were predicted correctly (see Table 1). These results indicate that there was a statistically significant relationship between attachment classification predictions made by the authors (based on observations of the clinical interview using the AA-CRS adapted from the AAI Scoring and Classification Manual) and AAI classifications that were made by Erik Hesse, Ph.D. The authors suggest that these statistically significant findings signify (a) that there is an underlying structure that is similar with respect to the AAI protocol and the AB-ISTDP clinical interview; (b) the AB-ISTDP clinical interview can provide a valid picture of the patient’s state of mind with respect to attachment experiences; (c) the AB-ISTDP method is a valid and potentially reliable method to assess change in the patient’s state of mind in psychotherapy outcome research (change toward earned secure attachments). The authors speculate that the differences in subclassification could be accounted for by variations and/or differences in biographical knowledge obtained by the the clinician versus that of the AAI coder (Hesse). In Case Number One, subclassifications were not assigned due to the authors’ initial attempts to work out a system of analysis that would capture the main classification only (once the authors became comfortable with the system of analysis for the first case, subclassifications were assigned for the remaining cases). In Case Number Three, the prediction (E3a predicted value) was based on preoccupation regarding childhood abandonment specifically, while AAI classification (F5 expected value) was based on an ultimately rational overview with respect to other traumatic experiences. Thus, the difference between main classification and subclassification for this case can be accounted for by superior biographical data on the part of the author.

| Case Number | DSM Diagnosis | Davanloo’s Spectrum | Defenses | Anxiety Manifestations | AAI Prediction | AAI Result |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Case # 1 | 300.01 Panic Disorder Without Agoraphobia | 3 | Smiling Humor Ignoring Repression Projection | Striated Muscle sympathetic parasympathetic | U/F/Ds | U/CC/F2/F4/Ds3 |

| Case # 2 | 300.21 Panic Disorder With Agoraphobia; 311 Depressive Disorder NOS; Dependent Personality Traits | 4 | Passive Compliant Dependent Vague Withdrawal Projection | Striated Muscle sympathetic Physical illnesses | E1 | E1/CC |

| Case # 3 | 300.01 Panic Disorder Without Agoraphobia; Borderline Personality Traits | 4 | Projection Acting Out Projective Identification | Striated Muscle sympathetic | E3a/F4b | F5/F4b/(other) |

| Case # 4 | 300.4 Dysthymic Disorder; V61.10 Partner Relational Problem; V62.82 Bereavement | 3 | Intellectualization Repression Projective Identification | Striated Muscle sympathetic | F1 | F1 |

| Case # 5 | 296.62 Bipolar I Disorder, Most Recent Episode Mixed; 301.50 Histrionic Personality Disorder | 4 | Ignoring Minimization Projection Somatization | Striated Muscle sympathetic Cognitive-perceptual | F/F4b | F/F4b |

| Case # 8 | Anxiety Disorder NOS, Chronic;Dysthymic Disorder; Borderline PD | 6 | Ignoring Neglecting Denial Splitting Dissociation | Striated Muscle Cognitive-perceptual | CC/E3/F4b | CC/E3/F4b |

| Case # 9 | Depressive Disorder NOS; Dependent PD With Masochistic Features | 6 | Relentless Self-Attack; Obsessions; Projection;Dental;Helplessness; ID-Mother as Victim Compliance/Defiance | Striated Muscle Parasympathetic Cognitive-Perceptual | CC/(E1/E2/F4b) | CC/(E1/E2/F4b) |

| Case # 11 | Panic Disorder Without Agoraphobia, Chronic; Dysthymic Disorder, Chronic;PD NOS With Dependent Traits | 7 | Minimzing Projection Slouching Detachment Humor Sarcasm ID-Aggressor Acting Out Dissociation | Striated MuscleParasympathetic Severe cognitive-perceptual | U/CC/Ds1/E2 | U/CC/Ds4/E-General |

Table I. PREDICTED AND EXPECTED VALUES FOR AAI CLASSIFICATION TOGETHER WITH OBSERVATIONS FROM THE CLINICAL INTERVIEW.

In Case Number Eleven, Ds4 was ruled-out as a predicted value for subclassification because the author was able to trace the fear of loss/death of the child to its source (the patient’s son was actually being stalked by gang members). Thus, Ds1 was assigned as the best-fitting subclassification for the predicted value (Ds4 was assigned as an AAI subclassification by Dr. Hesse because the fear of loss of the child through death could not be traced to its source). Again, we have an example of difference in predicted/expected values that can be explained by superior biographical data on the part of the author. The E2 was assigned as an alternative subclassification in Case Number Eleven due to pronounced intrapsychic conflict observed in the patient during the clinical interview (preoccupying anger surrounding a controlling and harsh mother). The difference between the E2 predicted value and the E-general classification assigned by Dr. Hesse can be explained by superior knowledge gained in the clinical interview as well as biographical data gained on the part of the author.

It is interesting to note that on two occasions in this study (Case Number Three and Case Number Eight), individuals who had been diagnosed with Borderline Personality Disorder were also assigned AAI classifications of E3. These results support the previous finding in the literature that the E3 classification is associated with borderline diagnoses (Hesse, 1999). In the E3 classification fear is the central and preoccupying affect, which corresponds to the DSM-IV differential diagnosis criterion indicating that frantic efforts to avoid real or imagined abandonment and transient, stress-related paranoid ideation are typically present in borderline diagnoses. Lyons-Ruth and Jacobvitz (1999) speculate that the E3 subclassification might be moved to categories associated with unresolved, disorganized, and/or unclassifiable mental states, since the fear-evoking experiences, including experiences of helplessness seen in E3 profiles, tend to correlate with unresolved fearful affects.

The authors conclude that the systematic ISTDP inquiry at the level of the stimulus (current, past, and therapeutic relationship) and response (defense, anxiety, and impulse/feeling) combined with the clinician’s knowledge of the patient’s clinical history can effectively substitute for the AAI interview, and therefore, yield an experiential reference from which to explore the patient’s state of mind using the Adult Attachment Clinical Rating Scale (AA-CRS). The authors of this paper anticipate that further research in the psychotherapeutic applications of the Adult Attachment Interview will provide important descriptive information for clinicians to understand the applications of attachment theory to the clinical practice of psychotherapy. Further research may contribute to the establishment of the procedures outlined as a reliable method for assessing a patient’s state of mind with respect to attachment experiences at a specific point during the course of treatment.

(2010). The efficacy of short-term psychodynamic psychotherapy for depression: A summary of recent findings. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica, 121(5), 398–399.Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

(2009). Short-term psychodynamic psychotherapy for somatic disorders: Systematic review of meta-analysis of clinical trials. Psychotherapy and Psychosomatics, 78(5), 265–274.Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

(2006). Short-term psychodynamic psychotherapy for common mental disorders. Cochrane Database System Review,18(4), article number: CD004687.Crossref, Google Scholar

(2008). Intensive short-term dynamic psychotherapy for DSM-IV personality disorders: A randomized controlled trial. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease, 196(3), 211–216.Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

(2011). The efficacy of short-term psychodynamic psychotherapy for depressive disorders with comorbid personality disorder. Psychiatry: Interpersonal and Biological Processes, 74(1), 58–71.Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

(2004). Adult attachment, parent emotion, and observed parenting behavior: mediator and moderator models. Child Development, 75(1), 110–122.Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

(1969). Attachment and loss: Volume I: Attachment. New York: Basic Books.Google Scholar

(2009). Adult attachment clinical rating scale. Unpublished manuscript, Pacific Graduate School of Psychology at Palo Alto University.Google Scholar

Cortina, M.Marrone, M. (Eds.) (2003). Attachment theory and the psychoanalytic process. London: Whurr Publishers.Google Scholar

(1978). Basic principles and techniques in short-term dynamic psychotherapy. New York: Spectrum Publications, Inc.Google Scholar

(1980). Short-term dynamic psychotherapy. New York: Jason Aronson.Google Scholar

(1995). Intensive short-term dynamic psychotherapy: Spectrum of psychoneurotic disorders. International Journal of Short-Term Psychotherapy, 10, 121–155.Google Scholar

(2001). Intensive short-term dynamic psychotherapy: Extended major direct access to the unconscious. European Psychotherapy, 2, 25–70.Google Scholar

(2010). The efficacy of short-term psychodynamic psychotherapy for depression: A meta-analysis. Clinical Psychology Review, 30(1), 25–36.Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

(1984) Adult Attachment Interview protocol. Unpublished manuscript, University of California at Berkeley.Google Scholar

(1985) Adult Attachment Interview protocol (2nd ed.). Unpublished manuscript, University of California at Berkeley.Google Scholar

(1996). Adult Attachment Interview protocol (3rd ed.). Unpublished manuscript, University of California at Berkeley.Google Scholar

(1999). The Adult Attachment Interview: Historical and current perspectives. In J. CassidyP. R. Shaver (Eds.), Handbook of attachment: Theory, research, and clinical applications (pp. 395–433). New York, NY: The Guilford Press.Google Scholar

(2008). The Adult Attachment Interview: Protocol, method of analysis, and empirical studies. In J. CassidyP. R. Shaver (Eds.), Handbook of attachment: Theory, research, and clinical applications (2nd ed., pp. 552–598). New York, NY: The Guilford Press.Google Scholar

(1999). Attachment disorganization: Unresolved loss, relational violence and lapses in behavioral and attentional strategies. In J. CassidyP. Shaver (Eds.), Handbook of attachment (pp. 520–554). New York: Guilford Press.Google Scholar

(1995). Attachment: Overview, with implications for clinical work. In S. GoldbergR. MuirJ. Kerr (Eds.), Attachment theory: Social, developmental, and clinical perspectives (pp. 407–474). Hillsdale, NJ: Analytic Press.Google Scholar

(1998). Adult attachment scoring and classification system, Version 6.0. Unpublished manuscript, University of California at Berkeley.Google Scholar

(1999). Attachment theory: Eighteen points with suggestions for future studies. In J. CassidyP. R. Shaver (Eds.) Handbook of attachment: Theory, research, and clinical applications (pp. 845–887). New York, NY: The Guilford Press.Google Scholar

(2002). Adult attachment scoring and classification systems, Version 7.1. Unpublished manuscript, University of California at Berkeley.Google Scholar

(2008). Studying differences in language usage in recounting attachment history: An introduction to the AAI. In H. SteeleM. Steele (Eds.), Clinical Applications of the Adult Attachment Interview (pp. 31–68). New York: The Guilford Press.Google Scholar

(1979). Individual psychotherapy and the science of psychodynamics. London: Butterworths.Google Scholar

(2010). Evidence-based psychodynamic therapy with personality disorders. In J. J. MagnavitaJ. J. Magnavita (Eds.), Evidence-based treatment of personality dysfunction: Principles, methods, and processes (pp. 79–111).Crossref, Google Scholar

Mikulincer, M.Shaver, P. R. (Eds.) (2007). Attachment in adulthood: Structure, dynamics, and change. New York: The Guilford Press.Google Scholar

(2011) Understanding and effectively treating anxiety symptoms with psychotherapy. Healthcare Couselling & Psychotherapy Journal, 11(1), 4–8.Google Scholar

(2011). Roadmap to the unconscious. London: Karnac.Google Scholar

(2004). Adult attachment: Theory, research, and clinical applications. New York: The Guilford Press.Google Scholar

Solomon, M.Siegel, D. (Eds.) (2003). Healing trauma: Attachment, mind, body, and brain. New York: W.W. Norton.Google Scholar

Steele, H.Steele, M. (Eds.) (2008). Clinical applications of the Adult Attachment Interview. New York: The Guilford Press.Google Scholar

(2009). The Adult Attachment Interview: A clinical tool for facilitating and measuring process and change in psychotherapy. Psychotherapy Research, 19, 1468–4381.Crossref, Google Scholar

(2006). When patients present with anxiety on the forefront. Ad Hoc Bulletin of Short Term Dynamic Psychotherapy, 10 (1), 35–69.Google Scholar

(2010). The collected writings of Josette ten Have-de Labije, PsyD. Del Mar, California: Unlocking Press.Google Scholar

(2011). Short-term psychodynamic psychotherapy for personality disorders: A critical review of randomized controlled trials. Journal of Personality Disorders, 25(6), 723–740.Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

(2006). Intensive dynamic psychotherapy of anxiety and depression. Primary Psychiatry, 13(5), 77–86.Google Scholar

(1997). Toward a theory of episodic memory: The frontal lobes and autonoetic consciousness. Psychological Bulletin, 121 (3), 331–354.Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar