Etiology, Pathogenesis, and Therapy According to Pierre Janet Concerning Conversion Disorders and Dissociative Disorders

Abstract

Pierre Janet’s works on conversion disorders or dissociative disorders has mainly fallen to the wayside in favour of Freud’s works. In the first part of this paper, Janet’s conception of hysteria is discussed and his place in French psychiatry described. Different aspects of Janet’s diathesis-stress approach are presented (particularly the pathogenic concept of fixed ideas), which refer not only to a conception of hysteria but also to traumatic (stress) disorders and other psychological disturbances. The second part of the paper details the varieties of Janetian therapeutic treatments of these disorders: the “liquidation” of fixed ideas by hypnosis and suggestion, confrontation techniques, which resemble contemporary cognitive behavioural approaches, and special cognitive (“logagogic”) interventions. Finally, we discuss the various treatment strategies based on psychoeconomic considerations such as physical or psychophyical therapies, psychoeducation, treatment through rest, and simplification of life for dealing with basic disturbances of psychic disorders.

Introduction

In the last few decades the formation of theories concerning conversion disorders or dissociative disorders was mainly determined by Freudian thought or its derivatives, whereas Pierre Janet’s works had fallen into oblivion (though Janet took up his scientific career as philosopher, psychologist, and psychotherapist long before Freud and continued to practise it longer than Freud did). The reason for this disuse may be that Janet’s scientific endeavours—like scientific theories in general—was not the starting point for a wider movement. His works were less speculatively conceived than Freud’s, which is why they now are appropriate as a starting point at which to reformulate the scientific explanation and treatment of conversion disorders and dissociative disorders (see: Bühler and Heim, 2001).

In the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders ([DSM-IV-TR] APA, see: Sadock, B. J. and Alcott Sadock, V., eds., 2003) conversion disorders belong to the somatoform disorders whereas dissociative disorders were classified in a category of their own. This split is justified because the symptoms (or deficits) of voluntary motor or sensory function and seizures or convulsions are the essential pathognomonic features of conversion disorders. The psychological factors are assumed to be converted into the bodily symptoms or deficits. In dissociative disorders, however, only psychological symptoms are affected, for example, the memory in dissociative amnesia, the unified consciousness in dissociative fugue, dissociative stupor, or dissociative trance, and identity in dissociative identity or depersonalisation disorder.

Janet’s Intellectual Background and His Place in French Psychiatry and Medical Psychology

Janet’s intellectual background is marked, first, by his training as to teach philosophy in the tradition of French spiritualistic philosophy. This school of philosophy had an enormous influence in 19th century France and the politics of science. The principal exponent was Maine de Biran (1766–1824), who stressed—in his “subjective” conception of psychology—emotional and volitive aspects of mental life in contradistinction to contemporary sensualistic conceptions of this science (see: Heim, 2006; Carroy, Ohayon, & Plas, 2006; Sjövall, 1967).

Secondly, positivism, represented by philosophers like Hippolyte Taine and Théodule Ribot, strongly influenced Janet. Particularly, Ribot’s contributions, e.g. his treatises on British and German psychology, strengthened the “pathopsycholgical” orientation of French psychology. Ribot believed that Claude Bernard’s approach to research in physiology was the model for the new “objective” psychology. In addition, Ribot made G.H. Spencer’s evolutionistic philosophy public in France (see: Brooks III, 1998).

Thirdly, Janet belonged to the medical-psychological school of thought or School of the Salpetrière, whose descriptive psychopathological approach had been, since Esquirol, the dominant trend in psychiatry. This school of thought, however, did not exclude psychological topics of the spiritualistic tradition discussed by scholars of subjective philosophy. Until nearly the middle of the 20th century, eminent French psychiatrists often had, like Janet, a double qualification as philosophers and physicians and were called “médecin-philosophes” (see: Bogousslavsky, 2011; Pichot, 1996; Postel & Quetel, 2004).

Janet’s philosophical dissertation of 1889, entitled “L’automatisme psychologique,” was a pathopsychological investigation concerning psychiatric inpatients. This famous study—carried out between 1882 and 1888—qualified Janet as a leading representative of objective psychology. He was supported by his uncle Paul Janet, one of the politically most influential spiritualistic philosophers, by Charles Richet, later Nobel-Prize winner of medicine, by Théodule Ribot, holder of the chair in pathological psychology at the reputable Collège de France, and, above all, by Jean-Martin Charcot, the famous neurologist who treated then-dispised hysterical patients with then-disapproved hypnosis. Janet, who meanwhile studied medicine, was appointed by Charcot as head of the psychological department of the Salpetrière, and he remained head of this department until he finally followed Ribot as holder of the chair of psychology at the Collège de France in 1902 (See: Brooks III, 1993; Ellenberger, 1970).

Etiology of Conversion Disorders and Dissociative Disorders

Basic Disturbances or Stigmata

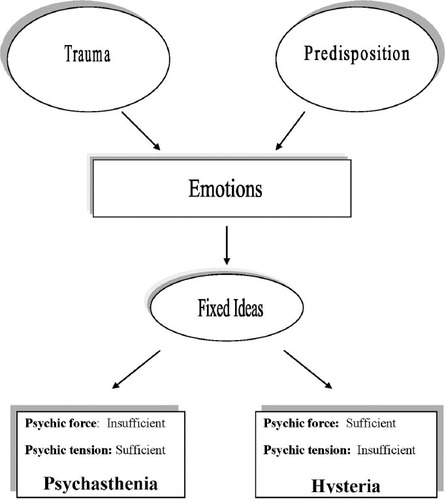

Pierre Janet proposes a diathesis-stress diathesis-model of conversion disorders and dissociative disorders and presumes as causes, first: basic disturbances, stigmata, or dispositional disorders, i.e. a fundamental vulnerability, and, second: accessory disorders like “fixed ideas” as effects of traumatic experiences (see: Heim and Bühler, 2006). The fixed ideas are highly variable and depend on the particular circumstances—including the biography—of the patient but not the basic disturbances, stigmata, or dispositional disorders

Because, basic disturbances, stigmata, or dispositional disorders and fixed ideas constitute different factors in the causal network of conversion disorders and dissociative disorders, the one may prevail on the other concerning the beginning and development of the sickness. If basic disturbances, stigmata, or dispositional disorders prevail, a “weakened psychic constitution” is the main cause for the beginning and the development of the sickness (Figure 1).

Figure 1 PSYCHOGENESIS OF NEUROSES

Compared with normal subjects, those with basic disturbances have dispositions to cognitive or psychic dissociation, i. e. to a weakening of the ability to perform cognitive or psychic synthesis, to narrowing of the field of personal consciousness, to absent-mindedness, to impairment of attention, to cognitive or psychic instability, to suggestibility, to reduction of sensibility, and to enhanced readiness for conversion, i. e. to an increased influence of cognitive or psychic factors on bodily processes.

The main or most basic disturbance of conversion disorders and dissociative disorders is a weakening in the ability to perform cognitive or psychic synthesis. This is the cause of the narrowing of the field of personal consciousness. Therefore, in conversion and dissociative disorders the personal consciousness is impaired. These patients are able to synthesise only a small part of psychic states or processes in a single personal consciousness. The impairment of personal consciousness explains the occurrence of dissociative amnesias because some psychic content may not be remembered by a particular personal consciousness. It also explains the occurrence of dissociative fugue, dissociative stupor, dissociative trance, and dissociative identity or depersonalisation disorders.

The second (or the other) consciousness(es) in dissociative fugue, dissociative stupor, dissociative trance, and dissociative identity or depersonalisation disorders is (are) but of a rudimentary form, being able to encompass only a limited number of sensations and ideas and, therefore, less able to control itself. This is why fixed ideas may develop without restriction in the rudimentary consciousness(es) and why they are even more powerful than in normal consciousness. The second or the other consciousness(es) is (are) similar to dream consciousness, which is a rudimentary consciousness itself.

Again, the impairment of personal consciousness is the cause of dissociative anesthesia. Dissociative anesthesia, however, is not a real anesthesia—an extinction of sensations—but a dissociation of psychic phenomena. The sensations that have left the normal personal consciousness continue to exist as parts of a different consciousness(es) and may be rediscovered there. Janet (1989) explains this as follows:

L’anesthésie systématisée ou même générale est comme une lésion un affaiblissement, non de la sensation, mais de la faculte de synthétiser les sensation en perception personelle, qui amène une véritable désagrégation des phénomènes psychologiques (p. 314).

(The systematised or even general anesthesia is like a lesion, a weakening not of the sensation but of the faculty to synthesise the sensations in a personal perception that leads to a real disaggregation of psychic phenomena. Translated by the authors.)

Elsewhere he remarked:

Dans l’hystérie, les phénomènes psychologiques ne pouvant plus être complèment réunis, se séparent nettement en plusieurs groupes à peu près indépendant l’un de l’autre. La personalié ne peut percevoir tous les phénomènes, elle en sacrifie définitivement quelques uns; c’est une sorte d’autonomie et ces phénomènes abandonnés se développent isolément sans que le sujet ait connaissance de leur activité.

(Because the psychic phenomena may not be completely united in hysteria, they clearly separate themselves in several more or less independently existing groups. The person is not able to perceive all the phenomena and definitely sacrifices some of them; this is a sort of autonomy and these abandoned phenomena develop in isolation without the person having knowledge of their activity. Translated by the authors.)

Because of the restriction of the field of consciousness, the patients are unable to enduringly unite all the sensations in one and the same personal perception. Therefore, in order to be able to perceive, they must select, and they select one or the other content of consciousness. This is the origin of instable personal perception.

Concerning anesthesia, Janet differentiates three stages of hysteria:

| • | First stage: the beginning hysteria. Here, the patients show no anesthesia but only some indifference concerning sensations, | ||||

| • | Second stage: the developing hysteria. Here exists a restriction in the field of consciousness but no unchangeable anesthesia. The sensations are not exclusively subconscious. They may become conscious through an enhancement of the stimulus or a change of attention. | ||||

| • | Third stage: the fully developed hysteria. The anesthesia is unchangeable. | ||||

In addition to disturbances in sensation, disturbances of voluntary motor functions are also caused by the restriction of the field of consciousness. The patients behave as if they were disturbed only in the voluntary, conscious, and attentively performed movements, not in habitualised and automatised movements, such as those movements performed in a absent-minded manner. It seems that psychic automatisms are even more pronounced. In general, these movements are slower and coarser in manner; they are not performed as a reflex.

As such, the patients are not conscious to basic disturbances. They are negatively characterised as a toning down or even suppression of sensations, memories, and movements. For Janet, these disturbances are proof of a weakening and exhaustion of central-nervous functions. Strictly speaking, these phenomena as such should be valued neither negatively nor positively, but according to the circumstances. If a conversion or a dissociation develops in an uncontrolled manner it is disturbing and therefore, valued as a negative. But if they are more or less intentional, as a yogi or fakir might show, no negative value is attached to them. For instance, intentionally or voluntarily performed dissociations are even strategies against torture, and as such they are positively valued faculties in resistance to torture.

The basic disturbances are based on hereditary dispositions or an acquired biological vulnerability. Therefore, in combination with an impaired ability for coping, conversion and dissociative disorders belong to the group of “adjustment or adaptation disorders” that should better be called “coping disorders” because adjustment and adaptation are kinds of coping.

Personality of Conversion Disorders and Dissociative Disorders

The personality of these disorders is affected, theatrical or histrionic, and dramatising. The subjects work themselves into affects and emotions, or they abandon themselves to them. Janet connects the personality of conversion disorders and dissociative disorders with the basic disturbances, mainly weakening in the ability to perform cognitive or psychic synthesis and restriction in the field of consciousness. He argues as follows:

Leurs enthousiasmes passager, leurs désespoirs exagérées et si vite consolées, leur convictions irraisonnées, leurs impulsions, leurs caprices, en un mot ce caractère excessif et instable, nous semble dépendre de ce fait fondamental qu’elles se donnent toujours tout entières à l’idée présente sans aucune de ces nuances, de ces réserves, de ces restrictions, qui donnent á la pensée sa moderation, son équilibre et ses transitions (Janet, 1909, p. 339).

(Their passing enthusiasm, their exaggerated and so easily consolable despair, their unreasonable convictions, their impulsiveness, their whims, in a word their excessive and unstable character seems to depend for us on this fundamental fact that they wholly abandon themselves to the present idea without any of these nuances, these reserves, these restrictions which give to the thought its moderation, its equilibrium and its transition. Translated by authors.)

Additionally, he describes supplementary personality features of conversion disorders and dissociative disorders, which, however, partially overlap with those of psychasthenic disorders (see: Janet, 1903) and are adduced in Table 1. They are not pathognomonic for both kinds of disorders. Some features are common to several disorders and thus characterise a psychically vulnerable personality. Histrionic personality features on the one hand and conversion disorders and dissociative disorders on the other were originally causally connected with the presumption that only subjects with those features seem tricky, complex, and ambiguous enough to sufficiently explain these polymorphous disorders. This connection, however, does not exist immediately but only mediately. Extraverted personality features prevail in polymorphous conversion disorders and dissociative disorders whereas introverted characteristics predominate in psychasthenic disorders.

| Hysterical Personality | Psychasthenic Personality | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Apathy—indifference, tendency to boredom | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Asthenia—weakness of will, lethargy, lack of stamina, monotonous behaviour (ALSO SEE: BENHIMA, 2010) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Table 1: COMPARISON OF HYSTERICAL VS. PSYCHASTHENIC PERSONALITY TRAITS

The psychic strain by the particular personality itself is the connecting link between personality on the one hand and the disorder on the other. The personality features mentioned by Janet are factors of psychic vulnerability because they contradict the principle of psychic economy, i. e. they highly waste “psychic energy” (i. e. tension or force). In his Harvard lecture (1937), which was based on his works on psychotherapy (1919;

1924) and on “La force et la faiblesse psychologiques” (1932), Janet thoroughly deals with the concepts of “psychic tension” and “psychic force” in the context of his general model of psychic resources concerning psychic disorders.

The metaphorical concepts of “force” and “tension” are taken from the language of electrophysics and transferred to psychology and, therefore, need some explanation. We propose that “force” is explained as potential energy (as opposed to actual, manifested energy) and “tension” is viewed as potential rate and extent of the activation of “latent energy”.

Janet assumes that “psychic force” and “psychic tension” are impaired differently in conversion disorders and dissociative disorders and psychasthenia. In psychasthenia the “psychic tension” is sufficient but not the “psychic force,” therefore, the subjects quickly become exhausted. Feelings of incompleteness, doubt, weakness of indecision, and other symptoms result from this imbalance of “psychic tension” and “psychic force” (Janet 1903, p. 675 f, p. 784 ff.). With conversion disorders and dissociative disorders, the relation between “psychic tension” and “psychic force” are inverse: the “psychic force” is sufficient but “psychic tension” is not. This is the cause why the field of consciousness is restricted and limited to few psychic states and processes.

The metaphors of “psychic tension” and “psychic force” need further characterisation through neurophysiological and neurochemical factors which, then, may explain the specificity of the disorders.

Traumata

Charcot and later Janet took additional causes concerning psychic disorders (besides organic and hereditary predispositions) into consideration: psychic traumata in the sense of psychologically impressing events. In his lectures during 1884 and 1885, Charcot was able to prove convincingly influence of these traumatic events on the genesis and the development of “hysterical” attacks and symptoms. Psychic traumata are conceived as life events triggering considerable affects and emotions (see: Janet, 1925, p. 289). In addition, chronic affects and emotions increase the effects of psychic traumata because, according to Janet, they are pathological phenomena, maladaptations of behaviour sto particular situations. So, affects and emotions are indispensable parts of psychic traumata.

Charcot showed that in some cases of “hysterical” paralysis caused by an accident, the emotion immediately originated by the accident is not the only cause of the disorder. The memories, the ideas, and the images of the accident, combined with the accompanying emotions and worries about the accident are as influential on the disorder as the accident. Here, the causes are mediate and not immediate ones (see: Janet, 1925, p. 208)

Concerning the diagnosis of disorders caused by traumata, Janet is a very cautious scientist. He preferred to explain the genesis of the symptoms of a disorder through their conformity to natural laws, not through accidental painful memories (see: Janet, 1919, p. 263). Symptoms should be considered as originated by accidental biographical causes only if such a consideration is indispensable, and taking the clinical context into account. Janet warns psychiatrists against abandoning themselves to speculative thinking. They have to carefully examine if the disorders necessarily take place in combination with the particular event, if there exists a parallelism between the disorders and the memories, and if both terms of the assumed causal relation are actually connected with each other, so that it is possible to change one by changing the other. For asserting a causal relation between event and disorder the influence must exist in the present; it is not sufficient that an event have had an influence in the past. All these precautions did not stop Janet from looking in the patient’s biography if an explanation of the disorders was not convincing in present findings. However, traumatic memories should be taken into account only if they recur in the present and if they convincingly condition enduring strain that causes exhaustion. As a link between traumata and disorder, Janet assumed a proneness or predisposition diathesis to affects or emotions. The psychic traumata manifest it and thus give occasion to a progressive loss of psychic energies (force or tension).

Pathogenesis of Conversion Disorders and Dissociative Disorders

Fixed Ideas

Basic disturbances and psychic traumata are but partial causes of conversion disorders and dissociative disorders. The fixed idea is an additional cause. It results from an enduring loss of psychic energy (force or tension) caused by traumatic affects or emotions. Janet connects his theory of psychic traumata and his overall nosology of conversion disorders and dissociative disorders. According to this hybrid theory, a patient is unable to wholly better integrate an awkward and painful experience of a life event into present life by coping with it and by fitting it as a coherent part into of life. On the contrary, the memory of the life event and the efforts to assimilate it into life continue persistently because the problems connected with it remain unsolved. There never exist feelings of triumph that normally take place after overcoming difficulties (see: Janet, P., 1919, p. 280).

The reiteration of the particular situation and the incessant endeavour to adapt or assimilate it into life, leads to a decrease of psychic energy (force or tension), to tiredness, to exhaustion, and to the origination of symptoms of sickness. This causes further affects and emotions.

Patients with fixed ideas of a former life event do not really remember this life event. Janet called this particular kind of memory “traumatic memory” of unassimilated life events. Therefore, patients are often unable to talk about this life event in a regular conversation, as is the case with common memory. Instead, the traumatic memory has to be inferred by psychological analysis of clues and hints. The fixed idea refers to something unsettled, i. e. something uncompleted, which Nietzsche named “resentment” and Viktor von Gebsattel called “presentification of the past” or “inhibition of becoming” (see: Bühler and Rother, 1999). Therefore, it is not surprising that fixed ideas resist changes, which Freud called “resistance.” And that resistance influences one’s conception of the world, of oneself and of the formation of interpersonal relations, which were named “transference” by Freud. Yet, it is not understandable why Freud attached so much significance to both of these qualities of fixed ideas.

Affects and emotions, being themselves combined attached to the senses, are of utmost importance in the genesis and development of fixed ideas. These affects-and emotions disconnect the overall structure of ideas and thus weaken the control of ideas by the person. Normally, ideas do not exist in isolation from each other but build up complexes as effects of a synthesis. In subjects with a sound psychic constitution, these complexes nest to become a superordinate system. That is, they become the system of the whole consciousness of a person. Traumatic memories based on fixed ideas, however, primarily develop in isolation from other psychic states or processes and without the knowledge or control of the person. They act in a way comparable to autosuggestions. The ideas become fixed and develop themselves autonomously and stay outside the personal consciousness and will of the patient (Janet, 1901). Therefore, the ideas may be characterised as subconscious (Bühler und Heim 2009). Charcot and Janet compared such fixed ideas with a parasite. Nowadays they would be called a harmful computer program, a computer virus, or a computer worm.

Vulnerability

Psychic traumata are not the only immediate causes of fixed idea development. Often traumata are caused either by a hereditary predisposition or an acquired weak psychic constitution. Exposure to external traumas further weakens the already frail psychic constitution, which itself is the source of increased affects and emotions, and thus continuing the existence of fixed ideas. The result is more damage to the psychic constitution and a vicious circle among affects, emotions, fixed ideas, and psychic disturbance ensues. Janet describes this vicious circle accurately:

C’est la depression préexistante qui prépare l’émotivite et qui bien entendu est augmentée encore par l’émotion nouvelle de telle manière que les troubles nerveux et mentaux de la depression se preécipitent en boule de neige (Janet, 1921, p. 221).

(The pre-existent depression paves the way for enhanced emotivity which, of course, is increased even more by a new emotion in a way that the nervous and mental troubles of a depression become faster and faster like an avalanche Translated by the authors).

Janet conceived his diathese-stress model on this basis. If the initial life event was very stressful then it occasioned severe emotions. In this case the emotionally originated fixed idea is very important for the genesis and development of the disorder. In other cases there is only a minor emotional reaction at the beginning of the disorder. Here, the weakened psychic constitution (faiblesse mental) is of utmost importance. It conditions an unstable psychic equilibrium, a loss of the ability to perform psychic synthesis, a paralysis of the association centers, and an impaired function of the sensory centers (Janet, 1898a, p. 155 ff; 1898b). Occasionally Janet compared psychic disorders with infectious diseases, the symptoms of which partly persist even if the infectious agent has already disappeared, so that a subsequent disinfection no longer has any influence on the processing of the sickness or curing. Therefore, a psychic disorder does not always disappear if a traumatically conditioned fixed idea has been removed. A proneness or vulnerability to psychic traumata remains, causing multiple relapses. The proneness or vulnerability to psychic traumata may be why new fixed ideas emerge, grow in strength, and engender a new disorder.

The causal procedures of psychic traumata may be summed up as follows. In the case of an already weakened psychic constitution, the trauma originates marked affects and emotions. Because of inappropriate patterns of reactions, the individuals are unable to cope with the difficult situation. They continue with their coping efforts. These repeated efforts occasion an exhaustion of psychic energy (tension or force) resulting in different types of psychic disorders. In case of sufficient tension but insufficient force, the ideas do not become subconscious but cause disorders that Janet calls “psychasthenia.” In case of insufficient tension but sufficient force, the ideas weaken the psychic synthesis and, by that, the connection of consciousness. The ideas become fixed as well as subconscious, the field of consciousness restricted, and the suggestibility increased. Janet names the disorders resulting from this process “hysteria.” These energetic conceptions of the aetiology of psychic disorders permit the possibility of the summed up causal effects of similar but also of different traumata as causes.

Therapy of Conversion Disorders and Dissociative Disorders

Charcot noted that the success of a therapy depends to a considerable extent on psychic hygiene, and having as an aim, among others, to eliminate pathogenic thoughts, images, or presentations. In this vein, Janet developed numerous therapeutic procedures. These procedures are presented here proceeding from the particular to the general.

Uncovering and influencing fixed ideas through psychological analysis

Generally speaking, the method of psychological analysis in Janet’s sense is not only appropriate for the treatment of conversion disorders and dissociative disorders but also for the therapy of psychasthenia because both maladaption disorders cause a weakening in the psychic constitution (i.e. a weakening of force and tension in Pierre Janet’s language). This psychic constitution should be strengthened through the liquidation of unsettled experiences. If the causes of a disorder are not found in the present life of a patient, it is justified to seek them in the past. This is done through analysis of the deeper layers of consciousness. Janet discussed this kind of treatment of traumatic disorders in his book Les médications psychologiques (1919, vol. II, pp. 204-307) under the heading “Treatment by mental liquidation,” and he proposed an interesting version of catharsis, i. e. abreaction (décharge), using the force of strong emotional reaction to re-establish hitherto dysfunctional adaptive responses of higher mental levels to traumatic experiences.

Psychological analysis in Janet’s sense of the term is apt to uncover traumatic yet subsconscious memories. In-therapy a subconscious fixed idea that wastes psychic energy (force or tension) is reintegrated into the whole of personal consciousness so that the loss of psychic energy (force or tension) is reduced. The reduction of these losses through the “liquidation” of fixed ideas explains the successes of psychological analysis. Janet elucidates this effect:

Après cette liquidation quelquefois pénible et coûteuse (. . .), l’esprit cesse de faire ces efforts d’adaptation qu’il répétait indéfiniment (Janet, 1924, p. 179).

(After this liquidation, sometimes painful and costly, the psyche stops making the efforts of adaptation which it repeated indefinitely. Translated by the authors.)

In many cases he recommends hypnosis and automatic writing as appropriate methods of psychological analysis because by activating tendencies that are latent in the waking state it is possible to retrieve memories. Janet also accepts dreams for this purpose, even if he definitely rejects sophistry in interpreting them. This is why dream analysis is not the primary method for investigating subconscious phenomena, though Janet accepts them as a window to subconscious processes that exist in parallel to the consciousness of the waking state. Dreaming is a kind of automatised psychic processes, that is it happens unintentionally and without the will of a person, and, therefore, it makes automatised psychic processes apparent. The automatic nature of dreams is why Janet accepts the dream analysis in psychotherapy, especially in cases of recurrent themes or content. Dreams indicate traumatic experiences that may stay in direct connection to psychic disorders because they are bound to latent (i. e. subconscious) tendencies. Latent tendencies may trigger dreams that may be wholly or partly remembered on awakening. In such cases the traumatic experiences are manifest in dreams. The distortions of the dream contents are the result of the nature of dream consciousness differing from waking consciousness (Janet 1909, p. 31). For Janet a dream has no meaning other than its manifest content. He rejects every symbolic interpretation of dreams. The analysis of dreams has to confine itself to recognising the automatised and recurrent processes in dreaming.

We, the authors, propose the following: Recognising automatised and recurrent processes in dreaming may become easier by using more abstract categories for description, thus enabling an optimal grasp of dream content and a more comprehensive discovery of recurrent processes. The use of more abstract categories for description is not, however, an interpretation of dreams in the Freudian sense, i. e. no amplification, but a reduction of the manifold of dream contents.

In particular cases Janet was able to show that discovering the subconscious fixed idea and rendering it conscious is sufficient either to diminish symptoms of sicknesses or to heal them completely. The healing process is accomplished by reducing the strength of a fixed idea that has become conscious through other conscious ideas, thus strengthening the psychic constitution through inhibiting losses of psychic energy (force or tension). Discovering unconscious traumata through psychological analysis is—apart from rare exceptions—but a first step in healing because not all psychic disorders vanish by making a subconscious fixed idea conscious. In some cases a pathogenic fixed idea has to be removed and replaced by a different nonpathogenic idea. Janet calls these quasi-surgical interventions “extraction,” “substitution,” “isolation,” or “dissociation”. Besides other techniques, for example, persuasion or explanation, hypnotic suggestions are helpful for these purposes. They are insinuated while the patient is in a subconscious state, and they are either induced by suggestions or occur spontaneously. The patients awaken from this subconscious state and have no memories of the processes that occurred. Another way to neutralise a fixed idea is to relativise the pathogenic nature of it through making positive aspects apparent.

Influencing Fixed Ideas Through Treatment by Suggestion

Because there is a disturbance in natural suggestibility in patients with conversion and dissociative disorders, treatment through suggestion is very important. Decreased ability for psychic synthesis, restriction of the field of consciousness, and thus, increased dissociation, are the causes of this natural suggestibility. Suggestions—conceived as the automatic development of particular ideas outside the will and the personal consciousness of patients—are clearly pathological phenomena. Such exaggerated development of an idea occurs when it is isolated from other psychic states or processes. Suggestions are, therefore, due to activation of a single tendency that is not complemented or completed by other tendencies. Suggestible persons never have more than a single idea in their restricted field of consciousness. This is why they are unable to unite several ideas in a single, personal consciousness. Janet explains:

En un mot, dans ce qu’on appelle suggestion, l’idée se développe complètement jusqu’à se transformer en acte, en perception et en sentiment mais elle semble se développer par elle-même, isolément, sans participation ni de la volonté, ni de la conscience personelle du sujet (Janet, 1909, p. 302).

(In a word, with what is called suggestion, an idea completely develops even to its conversion into an action, a perception, and an emotion but it seems to develop for itself and in isolation without the involvement of the will or the personal consciousness of the subject. Translated by the authors.)

The suggested idea develops as it does because it is isolated and does not counter ideas in the field of consciousness that opposite it and able to modify it. Consent to the suggestion takes place immediately and involuntarily without reflection or rational consideration. It happens like an impulse. Janet comments as follows:

La provocation d’une impulsion, qui constitue l’essentiel de la suggestion n’est en somme pas autre chose que l’activation d’une tendance sous une forme inférieure, avec un degré moindre de perfection à la place d’une activation de forme plus élevée (Janet, 1924, p. 126).

(All in all, the provocation of an impulse, which is the essential element of a suggestion, is nothing but the activation of a tendency on a lower level with a lesser degree of perfection instead of activation on a higher level. Translated by the authors.)

The automatic association of psychic elements must be possible to accomplish a suggestion, but the actual synthesis of these elements is altered or restricted. A pre-existing illness is a prerequisite for the alternation of psychic synthesis since psychically well persons maintain the ability for synthesis.

Janet tried to influence fixed ideas through suggestions. If such an influence is not immediately possible, then a fixed idea should likewise be replaced through suggestions and transformed into a more harmless idea, or dissected into its elements, which will be suggestively dissolved one by one. Janet himself describes this procedure:

L’idée fixe nous a paru être une construction, une synthèse d’un très grand nombre d’images; au lieu de l’attaquer dans son ensemble, il faut chercher à la décomposer, à détruire, ou à transfomer ses éléments, et il est probable que l’ensemble ne pourra plus subsister (Janet, 1894a, p. 128).

(For us the fixed idea seemed to be a construction, a synthesis of a great number of images; instead of attacking it as a whole, one should try to dissect it into single parts, to destroy or to transform its elements; then it is probable that the whole will not persist any more. Translated by the authors,)

Treatment through ordinary suggestion is complemented by hypnosis through activation of automatic rather than higher cognitive tendencies. This complement is very helpful because the natural suggestibility of patients with conversion disorders and dissociative disorders is increased during the hypnotic state. Through these procedures lower level tendencies are freed from the control of higher ones, and this occasions an immediate (asseritif) consent rather than a reflected (reflechi) one. Janet’s concept of hypnosis is connected with his overall psychological view of psychic tendencies (see Heim and Bühler, 2006). The low level of the middle tendencies or patterns of behaviour (conduites moyennes), i.e. the pithiatic or assertive (automatic consent or affirmation) stage with its suggestible imitation or unreflected consent, is very important for treatment through suggestion.1 Shortcomings in this stage are obvious: some steps leading to reflected beliefs are skipped and substitutions in the patient’s beliefs go unchecked. Janet believes that the phenomenon of suggestibility and suggestion may not be understood without in-depth knowledge of the pithiatic state of consciousness.

However, treatment through suggestion, and a fortiori through hypnotic suggestions, is limited.

First, it would be a wholly wrong understanding of a psychic image or presentation to restrict the cause of such disorders to a single fixed idea, and to think that it would be sufficient to remove it through suggestions. Secondary fixed ideas must not be overlooked. To do this would be to misunderstand essential elements of these disorders and to have an incorrect conception of psychic images or presentations.

Second, the ease with which the suggestions relieve patient suffering is simultaneously a symptom of a deep psychic dissociation. The more easily the cure is accomplished, the deeper psychic condition is bound. Therefore, Janet sees the treatment of conversion disorders and dissociative disorders through suggestions, and a fortiori through hypnotic suggestions, as problematic because these procedures replace “one evil with another.” If one symptom is removed through suggestions, another may emerge. The basic disturbances of patients with conversion disorders and dissociative disorders (their increased suggestibility) would not be improved by suggestions or hypnotic suggestions, but rather made worse. In addition to these considerations, it is not certain if the fundamental fixed idea is actually removed through the suggestive elimination of symptoms. These objections do not imply, however, that treatment through suggestions or hypnotic suggestions is not effective in particular cases (though it may fail in many others). Therefore, a trial of treatment through suggestions or hypnotic suggestions is always indicated.

Like every drug, suggestions are, according to Janet, useful in some cases and harmful in others. They are useful in weakening or suppressing subconscious fixed ideas that individuals cannot influence, and this enables the patients to recover from the loss of psychic energy (force and tension). Apart from these cases, Janet considers treatment through suggestion or hypnotic suggestion as harmful because it increases psychic dissociation, which is the cause of all dissociative symptoms. Janet remarks:

Du moment que vous pouvez guérir le sujet par suggestion, c’est qu’il est encore malade. Sauf des cas très rares, il ne me semble pas que l’on puisse arriver à guérir par suggestion l’état même de misère psychologique, qui estune condition essentielle de l’exécution des suggestions (Janet, P., 1889, p. 456).

(In the same moment as it is possible for you to heal persons through suggestion, they are still sick. Apart from very rare exceptions, it seems to me that it is not possible to heal the real condition of psychic suffering which is the essential precondition for suggestions to be effective, through suggestion. Translated by the authors.)

Janet even compares the craving to be hypnotised with morphine addiction and makes it responsible for a part of the disturbances of these patients. He argues:

Ces rechutes semblent fréquemment se compliquer par un besoin très intense qu’éprove le sujet, celui d’être hypnotisé de nouveau, d’être de nouveau commander, suggestionné par la personne qui l’avait guéri précédemment. C’est ce sentiment analogue à bien des points de vue à la morphinomanie, que j’ai étudié sous le nom passion somnambulique (Janet, 1911, p. 664).

(Many times these relapses seem to become even more complicated by a very strong desire of the patient to get hypnotised, led, and suggested by the person having cured them before. This craving which I have investigated using the expression “somnambulic passion” is comparable in many respects with morphine addiction. Translated by the authors.)

All in all, treatment through suggestion is a symptomatic therapy with many limitations, such as patient resistance to suggestions, transient relief, or the generation of additional symptoms, including dependence or even addiction. An additional qualifier: If fixed ideas influence interpersonal relations (or are triggered by them), an immediate effect on fixed ideas through suggestion or hypnotic suggestion is hardly possible, but a mediate one is possible through implicit shaping of interpersonal relations or explicit reinterpretation of them.

Influencing Fixed Ideas Through Treatment by Images or Presentations

Antagonistic-ideas, which are opposed to the pathologic fixed ideas, trigger deep emotions or affects so that a new equilibrium is affected in the whole system of consciousness. Janet recommends the concrete procedures of common counselling, words of encouragement, incentives, and specialised exercises with strengthening or constructive cognitions. He has summed up the procedures of his times used in treating traumatic disorders:

Les meillieurs procédés sont ceux qui déterminent l’assimilation de l’événement émotionnant, qui aménent le sujet à comprendre par la réfléxion, à y réagir correctement, à s’y résigner (Janet, 1924, p. 101).

(The best methods are those which determine the assimilation of the shocking events through inducing the subject to understand them through reflection, to react to them appropriately, and to learn to live with them. Translated by the authors.)

However, Janet viewed these methods only applicable in a limited way because of their shortcomings: high rates of relapse, fast habituation, high variability concerning persons and situations, and low transferability to other cases. In addition, fixed ideas are not fundamentally changed by these procedures because they, the fixed ideas, do not depend on the will and the rational affectability of the patients.

Janet, Cognitive Therapy, and Other Current Behavioural Therapies

It is not our intent to demonstrate that many ideas in modern psychotherapy were anticipated by Janet because psychotherapy has many “parents.” But Janet may be called a precursor of behaviour therapy and cognitive therapy. We can appreciate Janet’s holistic approach, including his model of personality, as paradigmatic in that it was engendered by extensive, careful clinical descriptions and cautious, theoretical “top-down” hypotheses were open to modification by empirical research. Not only was Janet’s inductive approach to studies similar to Eugen Bleuler’s influential conceptualization of schizophrenias, but also, Bleuler was deeply influenced by Janet’s studies of hysteria and psychasthenia than was hitherto assumed (see: Moskowitz & Heim 2011).The same influences hold for other conceptions of psychological disorders. Additionally, one should not ignore the usefulness of Janet’s conceptions bearing in mind the relevance of Albert Bandura’s “self-efficacy” model (1977) or Frederick Kanfer’s (1991) “self-management” model for the cognitive-behavioural therapies, as well as the recent shift to constructivist and dynamic conceptions (“third wave”) in cognitive-behavioural therapies.

In general, Janet’s methods resemble today’s cognitive-behavioural procedures for treating dysfunctional and affectively tinted thoughts and cognition complexes. His methods correspond the principles of cognitive-behavioural therapy that a therapeutically structured re-experiencing of traumata to neutralize phobic behaviour, will oppose fixed ideas and integrate the traumatic experience, thus allowing an appropriate reappraisal [of the trauma]. For instance, the cognitive-behavioural “narrative” method for treating posttraumatic stress disorders (PTSD) is implicitly based on Janet’s conception of subconsciousness (Janet, 1907a; Bühler & Heim, 2009; Fiedler, 2008). It consists of reintegrating dissociated emotional memories of traumata, conceived as temporarily unrelated elements that are context-free, into a chronological autobiographical context. Most modern approaches are congruent with Janet’s views that during traumatic experience there is a lowering of “mental strength,” that is, pathogenic associative learning processes prevent the synthetic processing of the trauma. Traumatic memories return because they are dissociated (or dis-integrated) fixed ideas evoked by stimulation. That is, deficient inhibitory processes (rather than voluntary recall) in autobiographic memory, lead to involuntary re-experiencing of the event. Janet also proposed a three-phase therapeutic strategy in PTSD: stabilization of the patient, synthesis of memory, and integration into daily life.

In addition, Janet’s approach resembles neo-behaviourism because of his reference to covert processes as well as overt behaviour. His concept may be understood as a dynamic resource-allocation model, which implies a functional model of psychological disorders. His blue print of a socio-genetic hierarchy of behavioural “tendencies” could represent a stimulating elaboration of the concept of behaviour. Janet also made systematic descriptions of psychotherapeutic interventions (Janet, 1919; 1924) which have similar differential-therapeutic objectives similar to present endeavours to integrate empirically supported therapies into a common psychological framework (see: Grawe 2002).

Nowadays, there exist a multitude of new cognitive-behavioural (or other somewhat related) approaches that focus on concepts like “schema,” “mindfulness,” “emotional regulation and processing.” They use narrative, imagery, and body-related procedures to promote assimilative processes in the treatment of traumatic disorders. They seem to confirm Janet’s prediction made in 1907 summarising his lessons about “Psychological analysis and the critics of psychotherapeutic methods” at the Collège de France:

Enfin les educations de l’attention, les traitements de l’émotivité, les diverses excitations qui se proposent de relever le niveau mental, constitutent les méthodes qui sont encre employées un peu au hasard, mais qui joueront un rôle de plus en plus grand dans l’education et dans le traitement de l’esprit (Janet 1907b, p. 710).

(“Finally the education of attention, the treatment of emotionality, the various excitations which intend to raise the mental level, form methods which are already applied a bit by chance, but which will play a more and more important role in education and in the treatment of the mind”. Translated by the authors.)

Such plausible links to current cognitive-behavioural therapies exist for the treatment of Posttraumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD), obsessive compulsive disorder (OCD), and depression as well as to behaviour therapy in general (see: Heim & Bühler, 2003; Heim & Bühler, 2006). Usually, almost no explicit references are made to Janet by authors of cognitive-behavioural therapy. One exception to this is Hoffmann (1998), who has developed an OCD treatment program based on Janet’s key-concept of “feeling of incompleteness,” which was further elaborated on by Ecker & Gönner (2008). In the same vein, Australian researchers (O’Connor et al. 2005) have discussed the therapeutic consequences of the Janetian view that OCD should not be conceptualized simply as an anxiety disorder. Additionally, Greenberg’s (2004) “Emotion-focused therapy” conceives of emotions or feelings in a manner that resembles Janet’s notion of feelings as secondary actions that regulate primary ones. For example, in Janet’s terminology, fear helps in avoiding dangerous ventures, thus preventing harm, fatigue assists by resigning oneself from endless efforts, thus preventing exhaustion, and effort assists in reaching a goal, and joy helps in finishing the action. All these emotions contain bodily felt sensations that bestow meaning to acting in concrete situations and these become part of an autobiographical storytelling. In Janet’s view they confer a substantial momentum to the evolution of personality. Greenberg’s “dialectical-constructivist” concept regards such a bottom-up process as essential in changing automatic emotional responding. His approach (including training in emotional awareness, regulation, and transformation) is a paradigm of Janet’s above-mentioned vision of “treatment of emotionality,” which is perceived as one important element of modern psychotherapy. Mentioned must be made that Janet’s pioneering role for those body-oriented therapies was worked out by Boadella (1997).

In the tradition of cognitive and hypnotherapeutic approaches, a group of Dutch and American researchers and therapists (Van der Hart, Nijenhuis, & Steele, 2006) has designed a comprehensive multimodal conception for treating chronic, severe traumatic disorders. The authors explicitly refer to Janet’s model of a dynamic personality, with its key concepts of action and its adaptive regulation by feelings. The authors conceive of dissociation as the manifestation of a disturbed interaction between adaptive action-systems of the person (i. e. the relation between actions directed to the demands of daily needs and the action systems necessary for extraordinary situations like defences against danger). Their comprehensive multimodal idea for treatment fosters harmony between the apparently normal personality (ANP) and the emotional personality (EP) dissociated from ANP, which causes secondary dissociations within the defensive systems of the EP and tertiary dissociations within the action systems of the ANP.

Another form of intervention in cognitive restructuring is Logagogy (Bühler, 2003, 2004). It is a demanding type of psychophilosophical intervention aimed at the spiritual sphere, insight, and reasoning of human beings to influence emotions and affects by means of verbal interventions and dialogue. It also includes written instructions such as aphorisms, epigrams, apophthegmata, paremias, gnomes, adages, proverbs, or sayings. The aim of Clinical Logagogy is the conduct of one’s life and the prevention of, as well as guidance for and support in, hopeless-seeming life crises or in insoluble-seeming conflicts. It is directed at thoughtful persons who are open to education and culture and willing to grasp their particular situation and to attempt to relativise the problems and conflicts by fitting them into general considerations. In his textbook of psychotherapy, Pierre Janet (1919, 1925) dedicated a chapter, “Philosophical Psychotherapy,” to forms of psychophilosophical intervention. However, he was sceptical about such interventions because he felt they depended too much on the particular therapist and training could not be generalized. We do not share his scepticism, though we acknowledging the limits of Logagogy.

According to Janet’s diathesis-stress model of dissociative disorders and conversion disorders, therapy for fixed ideas is more important than the treatment procedures of basic disturbances or stigmata. However, in cases of high vulnerability, principle demands that the basic disorders or stigmata receive equal treatment.

Treatment of Dissociative Stigmata (Basic Disturbances)

In the case of a still severely disturbed psychic constitution, a cure after having treated fixed ideas is not always lasting. In addition to the therapy for fixed ideas, basic disturbances or stigmata have to be treated because the general psychic constitution is a collateral cause of suggestibility and the fixed ideas themselves. Therefore, treatment has to cure the basic disturbances in, for example, psychic synthesis. All general treatment procedures help the psychic constitution in preventing or minimising unnecessary expenditures of psychic force and tension.

Physical or Psychophyical Therapies

Janet recommends general treatment procedures like physiotherapy, hydrotherapy, balneology, nutrition, and other methods to enhance sensibility. According to Janet, the physical or psychophysical as well as dietetic procedures are very helpful because they strengthen health in general and the nervous system or the psychic synthesis ability in particular. They prevent relapses after a treatment through psychological analysis or through suggestion.

Psychoeducation

In addition to the other methods, Janet recommends psychoeducation as a therapeutic procedure (Janet, 1911). In order to overcome the effects of unsuccessful adaptation, patients have to find new coping strategies that foster the ability to solve problems or to learn to live with the inevitable. Psychoeducative methods range from the uncomplicated method of “economizing” energy, for example, treatment through rest or isolation, and the more complex, such as activation of the other. Training of attention (L’éducation de l’attention) is especially worth mentioning here. Comparable to pedagogy, it is a kind of mental gymnastics that improves the patient’s ability to perform psychic synthesis through exercises. In turn, the increased ability to perform psychic synthesis prevents suggestibility and fixed ideas. Janet describes the training of attention (L’education de l’attention) as follows:

. . . [C’est] une méthode de traitement qui consiste à les (les hystériques) faire travailler céréralemant d’une manière régulière, comme des enfants à l’école (Janet, 1911, p. 675).

(. . . [It is] a method of treatment which consists in getting them (the hysterics) to do regular mental work like children in school. Translated by the authors.)

Here, modern cognitive or hypnotherapeutic procedures for treating histrionic personality disorders should be mentioned. In this connection the “ego state” is a core concept. Watkins and Watkins (1997), for example, define it as an organised system of experiences and behaviours connected by a common principle and separated by somewhat permeable borderline from different “ego-states.” As a psychotherapeutic approach for histrionic personality disorders, Watkins and Watkins (1997) propose a multilevel description of situations (encompassing thoughts, emotions and affects, bodily sensations, tendencies of behaviour, and feedback information of the [social] environment) activating mostly conflicting “ego states.” This approach can be combined with cognitive therapy connected with behaviour modification. The patients learn to be aware of their ego states by means of analyses of cognitive experiences and behaviours, and as a consequence, they learn to prevent, moderate, or adaptively change the effects of these mostly conflicting “ego states.”

Janet also proposed work therapy (a modification of it nowadays is called ergotherapy). The basic idea of such a therapy is to train higher tendencies, to broaden the field of consciousness, and to enable it to take in several ideas simultaneously as well as to synthesise them or oppose one another. Therefore, mechanical activities that may be carried out with low attention should be avoided. Rather, activities should be graded according to the attention required and the number of elements to be synthesized, i.e. according to their complexity. The tasks must neither be too undemanding nor too demanding. Here, parallels to Morita therapy are obvious.

Treatment through Rest

As general procedures to strengthen the psychic constitution, Janet suggests treatment through rest, isolation, and hypnotic sleep. In modern times Charcot was the first to introduce them as cures for treating psychic disorders. Treatment through rest is self-evident and needs no further characterisation. Isolation is characterised by Janet:

L’isolément consiste tout simplement à retirer le malade de sa famille, de son milieu habituel et à le transporter brusquement dans un endroit tout à fait inconnu pour lui (Janet, 1911, p. 642).

(Isolation simply consists in taking the patients away from their families, their ordinary social environment and bring them immediately to a place wholly unknown to them. Translated by the authors).

The basic idea is very simple, namely, to remove the patients from their pathological milieu. Through isolation the exhaustion caused by influences from the ordinary social environment of the patients can be reduced. Janet argues:

C’est dans leur famille, dans la présence de certains personnes, dans la conversation que se trouve l’origine de leurs idées fixes. Ces idées fixes sont sans cesse éveillées et alimentées par des fait journaliers et ne peuvent que grandir dans le milieu où elles ont pris naissance (Janet, 1911, S. 643).

(The origin of their fixed ideas is to be found in their family, in the presence of particular persons, in conversations. These fixed ideas are incessantly activated and nurtured by everyday incidents and become stronger and stronger in the milieu where they originated. Translated by the authors).

To distance the patient from the stressful environment, treatment through rest and isolation takes place in a sanatorium. To this extent, treatment through rest and isolation is another parallel to Morita therapy, however, the patients are not left to fend for themselves but they enter a therapeutic milieu. Without a doubt the patients take their fixed ideas with them to the new environment, but while there they do not think of them as much. Therefore, the fixed ideas are not incessantly activated by associations, and in a best-case scenario are forgotten. Additionally, isolation simplifies of the patients’ lives. This is no small advantage for patients whose ability for psychic synthesis is impaired.

Concerning treatment through rest by means of hypnotic sleep, Janet proposes three steps:

| 1) | Initiation | ||||

| 2) | Induction of hypnotic sleep, and | ||||

| 3) | Termination with the wakening phase. | ||||

Janet calls this procedure:

Un modificateur puissant des phénomènes psychologiques, capable de déterminer dans l’esprit, dans les souvenir, dans les actes des bouleversements remarquables (Janet, 1911, p. 654).

(A strong modificator of psychic phenomena able to provoke remarkable modifications of the psychic constitution in general, of memories, and of actions. Translated by the authors,).

He also writes:

Le sommeil hypnotique est surtout utilisé pour que le sujet exprime ses émotions persistantes, indique leur origine et consente à se laisser imposer des efforts de volonté et d’attention nécessaires pour modifier son équilibre cérébral (Janet, 1911, p. 651).

The hypnotic sleep is mainly used to make the subjects express their persistent emotions, show their origins, and consent to impose on themselves efforts of the will and attention necessary to modify the cerebral equilibrium. Translated by the authors).

Treatment through rest and isolation is but a first step. Another one has to follow: simplification of life.

Simplification of Life

Janet proposes simplification of life (simplification de la vie) as the most general procedure for treating the basic disturbances of dissociative disorders and conversion disorders. Yet simplification of life as an unspecific therapeutic procedure is not only appropriate for dissociative disorders and conversion disorders but also for psychic disorders in general, e. g. depression, schizophrenia, anxiety disorders, or some personality disorders. Simplification of life is even more important than ordinary treatment through rest and isolation because the faults and shortcomings of lifestyle and the conduct of one’s life become particularly obvious in psychic, psychosomatic, and even somatic disorders. They are symptoms of deeperlying failings of the human constitution and like measuring instruments, are appropriate and sensitive indicators of the faults and shortcomings in lifestyle and the conduct of one’s life. Janet mentions simplification de la vie:

Je le résumerai en un mot, c’est la vie facile dans laquelle tous les problémes de la famille, de l’amour, de la religion, de la fortune sont réduit au minimum, dans laquelle sont soigneusement écartées les luttes de chaquejour toujours nouvelles, les préoccupations de l’avenir, et les combinaisons compliquées (Janet, P., 1911, p. 678).

I sum up: In simple life all difficulties with the family, love, religion, fortune, and happiness are reduced to a minimum. In it the daily struggle for life, the worries about the future, as well as other complications and confusions of life are removed. Translated by the authors).

Because patients often get stuck (accrochés) in seemingly hopeless situations, the basic principle of life simplification is reducing unnecessary stress and keeping life as unaffected as possible They have to be freed (désaccrocher) of their seemingly hopeless situations by solving as many of their mostly complex problems of life as possible. One means of achieving this goal is to organise and structure life. This kind of treatment is also carried out by psychogogic or psychotherapeutic councelling and instruction in strategies for problem solving. Sometimes such a therapeutic approach becomes very difficult or even impossible, since for therapists may not be able to solve all the problems of their patients. Often the therapists can only give hints about heuristics for problem solving.

Although Janet discussed many treatment modalities, he did not have at his disposal should be mentioned an additional, rather unspecific treatment for basic disturbances of psychic disorders: psychopharmaceuticals.

(1977). Self-Efficacy. Psychological Review, 84, 1891–215.Crossref, Google Scholar

(2010). Die Konzeptionen der neurotischen, hysterischen und psychasthenischen Persön-lichkeiten bei Pierre Janet [Conceptions of Neurotic, Hysteric, and Psychasthenic Personality in Pierre Janet] (Medical Dissertation Julius-Maximilian University of Würzburg, Germany).Google Scholar

(1997). Awakening sensibility, recovering motility. Psycho-physical synthesis at the foundations of body-psychotherapy: the 100-year legacy of Pierre Janet (1856-1947). International Journal of Psychotherapy 2, 45–56.Google Scholar

(2011). Hysteria after Charcot: back to the future. In: Bogousslavsky, J. (ed) Charcot: a forgotten History of Neurology and Psychiatry. Frontiers of Neurology and Neuroscience, 29, 137–161Google Scholar

(1993). Philosophy and psychology at the Sorbonne, 1885-1913. Journal of the History of the Behavioral Sciences, 29, 123–145.Crossref, Google Scholar

(1998).The Eclectic Legacy. Academic Philosophy and the Human Sciences in Nineteenth-Century France. Newark: University of Delaware Press.Google Scholar

(2003). Foundations of Clinical Logagogy. Medicine, Health Care, and Philosophy, 6, 303–313.Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

(2004). Gedankensprünge zum Heil: Eine Anthologie zur Logagogik. [Mental Leaps to Well-Being: An Anthology of Logagogy] Norderstedt, Germany: Libri Books on Demand.Google Scholar

(2001). General Introduction to the Psychotherapy of Pierre Janet. American Journal of Psychotherapy, 55, 74–91.Link, Google Scholar

(2009). Psychopathological Approaches in Pierre Janet’s Conception of the Subconscious. Psychopathology, 42, 190–200.Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

(1999). Die Anthropologische Psychotherapie bei Victor Emil Freiherr von Gebsattel [Anthropological Psychotherapy of Victor Emil Freiherr von Gebsattel]. Fundamenta Psychiatrica, 13, 1–8.Google Scholar

, (2006). Histoire de la Psychologie en France. XlXe-XXe siècles. [History of Psychology in France. 19th and 20th Centuries] Paris: La DécouverteGoogle Scholar

(2008). Incompleteness and harm avoidance in OCD symptom dimensions. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 46, 895–904.Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

(1970). The Discovery of the Unconscious: The History and Evolution of Dynamic Psychiatry. New York: Basic Books.Google Scholar

(2006). Ein Blick zurück in die Zukunft: Pierre Janet überholt Sigmund Freud [Looking Back to Future: Pierre Janet Overtakes Sigmund Freud]. In P. Fiedler (Eds.), Trauma, Dissoziation, Persönlichkeit. Pierre Janets Beiträge zur modernen Psychiatrie, Psychologie und Psychotherapie. (pp. 35–56) [Trauma, Dissociation, Personality. Pierre Janet’s Contribution to Modern Psychiatry, Psychology, and Psychotherapy]. Lengerich: Pabst.Google Scholar

(2008). Dissoziative Störungen und Konversion. Trauma und Traumabehandlung [Dissociative Disorders and Conversion. Trauma and Treqtment of Traumata]. Weinheim, Basel: Beltz PVU.Google Scholar

(2002). Psychological therapy. Ashland, OH: Hogrefe and Huber.Google Scholar

(2004). Emotion-focused therapy. Clinical Psychology and Psychotherapy, 11, 3–16.Crossref, Google Scholar

(2003). Pierre Janet: Ein Fall für die moderne Verhaltenstherapie? [Pierre Janet: A Case of Modern Behaviour Therapy?]. Verhaltenstherapie und Verhaltensmedizin, 24, 205–224.Google Scholar

(2006). Philosophische Psychologie und positivistische Psychopathologie. In: In P. Fiedler (Eds.), Trauma, Dissoziation, Persönlichkeit. Pierre Janets Beiträge zur modernen Psychiatrie, Psychologie und Psychotherapie. (pp. 234–251) [Trauma, Dissociation, Personality. Pierre Janet’s Contribution to Modern Psychiatry, Psychology, and Psychotherapy]. Lengerich: Pabst.Google Scholar

(2006). Psychological Trauma and Fixed Ideas in Pierre Janet’s Conception of Dissociative Disorders. American Journal Psychotherapy, 60, 111–129.Link, Google Scholar

(1998). Zwänge und Depressionen. Pierre Janet und die Verhaltenstherapie [Compulsions and Depressions. Pierre Janet and Behavior Therapy]. Berlin: Springer.Google Scholar

(1889). L’automatisme psychologique, Paris: Alcan.Google Scholar

(1894a). Quelques définitions récentes de l’hystérie. [Some recent definitions of hysteria] Archive de Neurologie, 26, 1–29, p. 7.Google Scholar

(1894b). Histoire d’une idée fixe. Revue Philosophique, 37, 121–168. [Please include the English translations]Google Scholar

(1898a). Traitement psychologique de l’hystérie. [Psychological Treatment of Hysteria] In Robin, A. (Ed.): Traité de thérapeutique appliquée, Vol. 15, 140–216. Paris: Rueff.Google Scholar

(1898b). Névroses et idées fixes, Paris: Alcan.Google Scholar

(1901). The Mental State of Hystericals, p. 278 ff, New York: Putnam.Crossref, Google Scholar

(1903). Les obsessions et la psychasthénie. [Obsessions and psychasthenia] Vol. I. Paris: Alcan.Google Scholar

(1907a). A symposium on the subconscious. IV. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 2, 58–67Crossref, Google Scholar

(1907b). L’analyse psychologique et la critique des méthodes de psychothérapie. [Psychological analysis and the criticism of psychotherapeutic methods] In: Pierre Janet (2004) Lecons au Collège de France (1895-1934). [Lessons at the Collège de France (1895-1934)] L’Harmattan, Paris.Google Scholar

(1909). Les néevroses, Paris: Flammarion.Google Scholar

(1911). L’état mental des hystériques, [The mental state of the hystericals] Paris: Alcan.Google Scholar

(1919). Les médications psychologiques, vol. 2, Paris: Alcan. [E. PaulC. Paul (Trans.) Psychological Healing: A Historical and Clinical Study (1925), London: Allen & Unwin.]Google Scholar

(1921). La tension psychologique, ses dégrés, ses oscillations. [Psychological tension, its degrees, its oscillations] British Journal of Psychology (Medical section), 1, 209–224.Google Scholar

(1924). La médicine psychologique, Paris: Flammarion. [H.M. GuthrieE.R. Guthrie (Trans.), Principles of Psychotherapy (1924), New York: MacMillan 1924)]Crossref, Google Scholar

(1930). L’analyse psychologique. [Psychological Analysis] In: Psychologies, Worchester, MA: Clark University.Google Scholar

(1932). La force et la faiblesse psychologqiues. [Psychological strength and weakness] Paris: Maloine.Google Scholar

(1937). Psychological strength and weakness in mental diseases. In: Factors Determining Human Behaviour. Harvard Tercentenary Publications. p. 64–106. ©Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.Google Scholar

(1991). Self-Mangement and Self-regulation. Berlin: Springer.Google Scholar

(1996). Cognitive therapy of dissociative symptoms associated with trauma. British Journal of Clinical Psychology, 35, 325–340.Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

(2011). Eugen Bleuler’s Dementia Praecox or the Group of Schizophrenias (1911): A centenary appreciation and reconsideration. Schizophrenia Bulletin 37, 471–479.Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

(2005). Evaluation of an inference-based approach to treating obsessive-compulsive disorder. Cognitive Behaviour Therapy, 34: 148–163.Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

(1996). Une Siècle de Psychiatrie [A century of Psychiatry]. Le Plessis-Robinson: Synthélabo.-Google Scholar

(2004). Nouvelle Histoire de la Psychiatrie. [New History of Psychiatry] Paris: Dunod.Google Scholar

Sadock, B. J.Alcott Sadock, V., (Eds.) (2003). Kaplan and Sadock’s Synopsis of Psychiatry, Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott, Williams and Wilkins.Google Scholar

(1967). Psychological Tension. An analysis of Pierre Janets concept of “tension psychologique” together with an historical aspect. Norstedts: Svenska Bokförlaget.Google Scholar

(2006). The Haunted Self. Structural dissociation and the treatment of chronic traumatization. New York, London: W.W. Norton.Google Scholar

(1997). Ego-States. Theory and Therapy. New York: W.W. Norton.Google Scholar