The Significant Other History: An Interpersonal-Emotional History Procedure Used with the Early-onset Chronically Depressed Patient

Abstract

An interpersonal-emotional history procedure, the Significant Other History, is administered to the early-onset chronically depressed patient during the second therapy session in the Cognitive Behavioral Analysis System of Psychotherapy (CBASP). Patients are asked to name up to six significant others and answer two questions: (1) What was it like growing up with or being around this person? (2) What is the emotional “stamp” you take from this relationship that informs who you are today? An interpersonal-emotional theme reflecting the early learning history of the patient is derived from these “stamps” or causal theory conclusions. One transference hypothesis (TH) is derived from the Significant Other History (SOH) and is formulated in one sentence, such as “If I do this, then the therapist will likely do that” (e.g., “If I make a mistake around Dr. E, then Dr. E will label me ‘stupid’ or ‘incompetent’”). The transference hypothesis highlights the interpersonal content that most likely informs the patient’s expectancy of the therapist’s reactions toward him or her. Throughout the therapy process, the therapist will proactively employ the transference hypothesis in a technique known as the Interpersonal Discrimination Exercise to help patients cognitively and emotionally discriminate the practitioner from hurtful significant others. The goal here is to increase the patient’s felt safety within the therapeutic dyad and eventually to generalize the felt safety to the patient’s other relationships.

Foreward

The present article introduces the Significant Other History ([SOH], McCullough, 2000, 2006; McCullough, Lord, Conley & Martin, 2010), an interpersonal-emotional history procedure used to guide Cognitive Behavioral Analysis System of Psychotherapy (CBASP) clinicians in their treatment of the chronically depressed patient. While the SOH has been used in two large clinical trials with chronically depressed patients (Keller, McCullough, Klein, Arnow, Dunner, Gelenberg, et al., 2000; Kocsis, Gelenberg, Rothbaum, Klein, Trivedi, Manber, et al., 2009), a formal description of the procedure has not been presented or discussed in detail in psychotherapy journals.

Introduction

The CBASP model of treatment for early-onset chronic depression (DSM-IV, APA, 1994) is essentially a learning-based model of psychotherapy (McCullough et al., 2010), and is the only psychotherapy model developed exclusively for the treatment of chronic depression (McCullough, 2000, 2006). McCullough and others (e.g., McCullough, 2006, 2010; McCullough, et al., 2010; McCullough & Penberthy, 2011) argue elsewhere that early-onset chronic depression is a refractory mood disorder maintained by a longstanding and pervasive pattern of interpersonal avoidance. The avoidance behavior appears to be fueled by felt interpersonal fear that has been widely generalized across persons and situational cues/contexts (Bouton, 2007; McCullough, 2008a; McCullough, et al., 2010; McCullough & Penberthy, 2011). The interpersonal avoidance pattern can be so debilitating that it perceptually disconnects the patient from others. This leaves the person orbiting in a lifetime pattern of repetitive interpersonal sameness. This childlike egocentric-pattern, where the person is not informed by his or her interactions with others is labeled, preoperational functioning (McCullough, 2000, 2006; McCullough et al., 2010; McCullough & Penberthy, 2011; Piaget, 1923/26; Wilbertz, Brakemeier, Zobel, Harter & Schramm, 2010; Zobel, Werden, Linster, Dykierek, Drieling, Berger, et al., 2010). Preoperational functioning has been described in detail elsewhere (McCullough, 2000, 2006; McCullough et al., 2010) and has been investigated under the labels Theory of Mind (ToM) and mentalization (e.g., Inoue, Tonooka, Yamada, & Kanaba, 2004; Inoue, Yamada, & Kanaba, 2006; Wilbertz et al, 2010; Zobel et al., 2010; Schnell, Bluschke, Konradt & Walter, 2011). Both constructs, ToM and mentalization, describe the mental ability to infer another’s beliefs, affective states, or intentions as one aspect of psychological maturity. This inter-personal capacity requires that the individual be able to “stand outside” him- or herself perceptually (a formal operational thought capability) and view another within a non-egocentric social context. In short, ToM and mentalization require empathic capabilities, a mental capacity that early-onset chronic patients do not possess.

Psychological Insults and Trauma

The interpersonal fear noted above more often than not appears to stem from a long-standing developmental history of either (a) psychological insults and/or (b) trauma (McCullough, 2006, 2008a; McCullough, et al., 2010) received at the hands of maltreating caregivers or Significant Others (SOs). Cowan (1978) and others (Cicchetti & Barnett, 1991; Guidano & Liotti, 1983; Hammen, 1992; Hammen, Burge, Daley, Davila, Paley & Rudolph, 1995) suggest that the entire emotional universe of the child is centered on the early attachment he or she achieves with his or her caregivers, particularly the mother. These early attachment relationships influence the infant’s interests toward the environment, feelings of respect for others, general interpersonal feelings toward others and the ambient emotional tone that permeates all cognitive constructions. An aversive developmental-attachment environment, filled with years of psychological rejection from maltreating caregivers, demeaning comments or emotional neglect, is often a characteristic feature of early-onset chronic depression. These conditions may not satisfy a more traditional definition of trauma; however, like traumatic events, they contribute to the exacerbation of the early-onset disorder (Cicchetti & Barnett, 1991; Cicchetti & Toth, 1998; Hammen, 1992). It is for this reason that we have coined the term, psychological insult as being one contributory factor in the onset of childhood/adolescent chronic depression. The authors (McCullough, 2008a; McCullough, et al., 2010) define psychological insult as a continuous series of experiences, encountered by the developing child or adolescent, that are associated with interpersonal punishment/rejection and are of a ‘low grade’ nature; in contrast, trauma signifies one or more life threatening or ‘high grade’ dangers the individual experiences (e.g., sexual and/or physical abuse, actual parental abandonment, emotional or physical neglect: McCullough, 2008a; Nemeroff, Heim, Thase, Klein, Rush, Schatzberg, et al., 2003; Wiersma, Hovens, van Oppen, Giltay, van Schaik, Beekman, et al., 2009).

Goals of SOH

The Significant Other History, a CBASP procedure administered during session two of treatment, samples the interpersonal-emotional history of the early-onset patient focusing on his or her experiences with SOs (McCullough, 2000, 2006; McCullough, et al., 2010; McCullough & Penberthy, 2011). The SOH is administered to achieve three goals:

| (1) | to gain self-report access to the individual’s emotional history with malevolent SOs so that the sources of the interpersonal fear can be identified (i.e. who inflicted the psychological insults and/or trauma), | ||||

| (2) | to obtain specific information suggesting how the patient was behaving or what the patient was doing when the pain/injury was administered by maltreating SOs (Such information further illuminates the nature of the person’s interpersonal fear and helps the therapist construct a relevant transference hypothesis. [TR]), | ||||

| (3) | to access information that will ultimately be used to assist the preoperationally functioning adult patient to achieve two-person, interpersonal functioning (Kiesler, 1996, 1988) with the practitioner (this step is achievable only after the first two goals are realized). This third goal exposes an important issue in interpersonal theory that needs clarification and is briefly discussed below. | ||||

Clarification of the Circularity, Two-Person Assumption in Interpersonal Theory as it Pertains to Early-Onset Chronic Depression

The Cognitive Behavioral Analysis System of Psychotherapy is described in the literature as an interpersonal model of psychotherapy (McCullough, 1984, 2006, 2008b; McCullough, 2010; McCullough, et al., 2010; McCullough & Penberthy, 2011). As noted above, many early-onset chronically depressed patients are perceptually disengaged from others (i.e., their social environment) in informing ways. Several labels have been proposed for this phenomenon such as “rigidity” (Wachtel, 1973), “indiscriminant responding” (Mischel, 1973), and “consistent behavior across situations” (Moos, 1968; as summarized by Kiesler, 1996, p. 196). These labels aptly describe chronically depressed patients as they consistently behave in an interpersonally rigid and indiscriminant manner, regardless of persons or situations. This interpersonal style is best characterized as “interpersonal sameness.”

It is the chronically ill patient’s functional sameness that exposes the issue we must clarify. Interpersonal theory assumes, a priori, that person-to-person transactions involve bidirectional circularity (Kiesler, 1996). Kiesler writes: “Interpersonal transactions consist of two-person mutual influence. Causality is simultaneously bi-directional; it is circular (Danziger, 1976) rather than linear” (Kiesler, 1996, p. 5).1

The two-person mutual influence model is illustrated below with the arrows indicating the directions of interactional flow:

The patient with early-onset chronic depression does not function in a circular interpersonal way when treatment begins (McCullough 2000, 2006). Given the pervasiveness of interpersonal avoidance, intra-personal not inter-personal functioning best describes the untreated chronic patient. Through his Maladaptive Transaction Cycle, Kiesler (1985, 1986, 1988; 1996, pp. 194-197) attempts to address the patient’s lack of circularity by demonstrating how metacommunicative feedback can be administered to a dysthymic (chronic) patient. Metacommunication is a verbal interpersonal feedback strategy that communicates how the patient’s behavioral impact is affecting the clinician (e.g., “When you do this, you make me feel like. . . .”). His conceptualization of the psychopathology of dysthymia and its treatment derives from Coyne’s (1976) interactive model for depression, which suggests that depression is largely an interactional problem. Chronic depression is more than simply an interactive dilemma, and it is not modifiable by corrective interpersonal feedback alone. At the beginning of treatment, the patient with early-onset chronic depression does not behave in a two-person manner. Therefore, the circularity assumption of interpersonal theory does not adequately describe the patient’s idiosyncratic functioning (Leary, 1955, 1957; Leary & Coffey, 1954; Kiesler, 1982, 1988, 1996; Sullivan 1953a, b). The patient’s one-person functioning dilemma is illustrated below: Note that the psychotherapist’s behavior does not penetrate the wall of interpersonal fear at the beginning of treatment:

Simply put, it is difficult to adhere to an interpersonal view of psychotherapy with a patient who is not influenced in a circular or bi-directional way and who is entrapped behind a refractory wall of interpersonal fear. Thus, the essential work of the CBASP clinician is to teach patients to behave interpersonally.

Felt Safety

The CBASP model has been designed specifically to open the “circularity” loop the patient has kept closed for many years by breaking through the patient’s wall of interpersonal fear and establishing a zone of felt safety. This felt safety must be established so that intra-personal functioning can be counter-conditioned with dyadic reciprocity (McCullough, et al., 2010). Successfully establishing interpersonal safety prepares the way for the patient to master the next step, which is, learning to function interpersonally and to generate empathy, important steps to acquire before patients can break out of their refractory intra-personal isolation. Once felt safety is established in the therapeutic dyad, patient behavior can assume a circular and/or bi-directional causal capability. The SOH will play a central role in this change process. In the sections to follow, we will demonstrate how the SOH provides essential information the practitioner can proactively utilize to jump-start the opening process.

Returning to the major aim of the paper, we now describe how the origins of the core interpersonal fear are identified in the SOH, how CBASP practitioners construct the TH using the causal theory material and lastly, how clinicians administer the TH to teach patients to function interpersonally and to generate empathy.

Clarifying the Origins of the Core Interpersonal Fear

Representative Early Abuse Material Available from Recent Research

Before describing the SOH procedure, it may be helpful to readers for us to illustrate some typical psychological insult/trauma histories taken from a representative sample of patients with early-onset chronic depression. These histories are drawn from Elisabeth Schramm’s personal files transcribed during a recent study of early-onset chronically depressed patients. The project (Schramm, Zobel, Dykierek, Kech, Brakemeier, Kültz et al.’s, 2011) was completed recently in Freiburg, Germany and compared the treatment efficacy of CBASP to that of Interpersonal Psychotherapy ([IPT] Klerman, Weissman, Rounsaville & Chevron, 1984). The 30 early-onset patients received 22 sessions of psychotherapy and 15 patients with early-onset chronic depression were randomized to each treatment cell. The researchers defined early trauma as an experience of emotional/physical/sexual abuse or emotional/physical neglect before age 18 years and a score in the moderate-to-severe range on the Childhood Trauma Questionnaire ([CTQ] Bernstein, Fink, Handelsman, Foote, Lovejoy, Wenzel et al., 1994). Seventy-nine percent in the Schramm et al. sample met criteria as early trauma subjects. Emotional neglect and abuse were the modal categories endorsed on the CTQ followed by physical neglect and sexual and physical abuse. E. Schramm (2011) randomly generated a list of 4 patients from her early-trauma group to illustrate the typical developmental histories of this cohort. All of the 4 subjects produced CTQ trauma scores in the severe-to-extreme range.

Patient 1 was a 21-year-old female reporting extreme sexual and physical abuse (beatings) from ages 5 years to 11 years by her stepfather. She reported that he screamed at her and threw her favorite stuffed animals in the trash. She recalled him saying to her: “I will be your first sexual partner as soon as you turn 12.” She also reported that her mother never protected her from her stepfather.

Patient 2 was a 28-year-old female who experienced severe-to-extreme emotional neglect and abuse coupled with physical and sexual abuse. The patient recalled that her mother often took the patient on dates in a car while the mother had sex with her male friends.

Patient 3 was a 42-year-old female with a history of severe-to-extreme physical and emotional abuse as well as neglect. As a young child the patient worked hard on the family farm and was often physically beaten by her father. She described her life as one in which she had never known a “decent” human being.

Patient 4 was a 54-year-old female who reported severe-to-extreme sexual and emotional abuse and neglect. The patient’s mother made it clear that she never wanted her, and she ignored and ridiculed the patient throughout the time the patient remained at home. The patient also reported a history of her biological father sexually abusing her.

When developing children are overwhelmed by the dangers of an abusive or neglectful home life, normal development is thwarted because the children’s energies and behaviors are not directed towards growth but towards surviving the “hell of the family” (Drotar & Sturm, 1991; Money, 1992; Money, Annecillo, & Hutchinson, 1985). McCullough (2000, 2006) writes that among many adult early-onset patients a failure to mature cognitively and emotionally is often painfully evident in the way the patients talk and behave.

The first author recently treated a preoperational patient who presented with a destructive developmental history similar to the four cases described above. The following conversation took place during an early session and provides an example of the primitive verbal style and behavior clinicians often confront with early onset patients:

Patient : The company photographer didn’t take my picture at the company picnic. He took Susan, Jane, and Mary’s pictures but not mine. He didn’t take my picture because he didn’t like me.

JPM : Did you know this man previously and did you ask him to take your picture?

Patient : No, I didn’t know him, and I didn’t ask him to take my picture. It wouldn’t have mattered. He wouldn’t have done it because he doesn’t like me.

JPM : How do you know he doesn’t like you?

Patient : I just know it. I just believe he doesn’t. Nobody likes me.

Reviewing the four abbreviated abuse histories and this example conversation between a therapist and patient make it easier to understand why early-onset chronically depressed individuals present with a pervasive interpersonal fear of others. These fears result in a generalized, interpersonal avoidance pattern that acts to maintain the preoperational, intrapersonal functioning of the chronically depressed adult. We turn our attention now to a description of the SOH procedure.

The Significant Other History Procedure

At the end of session one, the patient is asked to bring a list of up to six Significant Others (SOs) to the next session. The SOs are carefully defined as the people around whom the patient grew up or with whom he or she currently interacts. All of these major players have significantly influenced the direction the patient’s life has taken as these are the individuals who have left their emotional stamp or mark on the person. In short, a SO denotes a person who has exerted either a positive or negative influence on the way one lives, thinks and feels. Patients are then instructed that during the next session the list will be reviewed with two goals in mind: (1) to recall several memories (with associated affect) to obtain a description of what it was like growing up or being around each SO; (2) to pinpoint the emotional stamp or mark the patient bears today because of each SO’s influence. In CBASP the “stamps” are labeled causal theory conclusions (McCullough, 2000, 2006) denoting their influence on the patient’s current life. Cognitive Behavioral Analysis System of Psychotherapy clinicians usually write the SOH material on a large flip chart or dry erase board in full view of the patient.

Common Challenges in Administering the SOH

Administering the SOH will be the first time the clinician asks the preoperational patient to think abstractly; that is, requests the individual to take a step back perceptually and to form causal theory conclusions about the stamps/marks he or she bears from several SOs. Some patients have difficulty completing this abstractive step and have to be assisted to construct these conclusions. Others respond in a vague manner and are unable to deduce any conclusions; in these cases, the clinician must infer the causal theory conclusions from the history. The procedural format of the SOH is shown below in Table 1.

| SIGNIFICANT OTHER HISTORY PROCEDURE DURING SESSION 2 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Table I. SIGNIFICANT OTHER HISTORY (SOH) PROCEDURE

As stated earlier, the exercise is essentially an interpersonal-emotional history procedure because of the way the SOH highlights the patient’s learning history. Patients frequently describe previous therapy experiences in which they were asked to “talk about” their pasts as well as discuss important persons in their lives. Such techniques inadvertently position the patient in an observer role when they talk about their SOs. Not infrequently, these individuals will say that they experience little or no emotional reaction when talking about the past. However, organizing one’s personal history in a SOH format positions the patient in a participant role. The patient describes specific hurtful experiences perpetrated by specific SOs and the consequences or influences they bear from these relationships. The SOH exercise often evokes significant emotional arousal that ranges from moderate-to-extreme felt discomfort. Since the procedure is done early in therapy (session 2), when many patients have not yet learned to trust the therapist, a retraumatization experience cannot always be avoided. Part of the pervasive avoidance style of the patient has included not recalling painful memories. The SOH may exacerbate painful associations that are connected to specific memories. The clinician must end the SOH exercise by discussing the explicit material written on the flip chart (e.g., “What is it like for you to see all this information written on the flip-chart?”) and then address any discomforting affect that may be present.

Finally, it must be noted that the SOH is primarily administered for the benefit of the clinician. That is, the information gleaned from the SOH will clarify and help define the therapist’s role with a patient by providing relevant information about the nature of the interpersonal fear the person brings to treatment. The history may also alert the practitioner to potential “relational pitfalls” that lay ahead and that, when wisely avoided, prevent the individual from prematurely leaving treatment. For example, a male therapist may assume that a friendly and helpful interpersonal demeanor is an effective therapeutic stance; however, with a female who presents with a sexual abuse history where her stepfather was always friendly and helpful prior to making sexual advances, the SOH will prevent the clinician from unquestionably relying on this interpersonal style.

Soh and the Autobiographical History Research Tradition

The SOH procedure clearly falls within the purview of the autobiographical memory (AM) research literature (Conway & Pleydell-Pearce, 2000; Williams, Barnhofer, Crane, Hermans, Raes, Watkins et al. 2006; Williams, Barnhofer, Crane & Beck, 2005). However, there are some notable differences between the procedure and goals of the SOH and the experimental elicitation procedures and goals involved in AM studies. First, in SOH it is the experienced emotional affect of the associated memory that is of primary importance, not the quality of the recalled memory. Secondly, the SOH is a clinical exercise used to access information solely for the construction of a transference hypothesis, which allows for future interpersonal discrimination between the psychotherapist and the maltreating significant others. Finally, the SOH has been studied only within the context of CBASP treatment for chronically depressed patients.

Soh and An Illustrative Case History

A case history of a 43-year-old female, Anne, is briefly presented below to illustrate the kind of SO material and the causal theory conclusions that are evoked in the SOH exercise.

Case

Anne was diagnosed “double depression” (Keller, Lavori, Endicott, Coryell & Klerman, 1983) and reported a dysthymia onset around age 13 years. She had not received previous treatment and described a 30-year history of depression with a minimum of 3 to 4 major depressive episodes. Most remarkable was her psychological insult and trauma history. When she was 10, her father died after a lengthy illness and her mother remarried while Anne was still in elementary school. The step-father was alcoholic and Anne’s mother worked at a full-time job. While Anne’s mother was at work, the step-father physically abused Anne, beating her with a belt whenever she disobeyed the house rules, and he often forced the child (from ages 11 to 16) to have sex with him. Anne never told her mother of the abuse nor did Anne know if her mother knew or suspected the abuse. “To escape” from the family, Anne married at age 17. Her husband was also alcoholic and physically abusive. She divorced him two years later.

The patient completed high school and has remained unmarried. She has worked for the past 20 years as a cashier in a pharmacy. Her Significant Other list included: Mother, Biological father, Step-father, Husband.

Mother: Emotionally distant, made me feel unlovable; she was always working. Mother rarely prepared meals, and most of the time, I had to fix my own meals as well as do the grocery shopping. She and my step-father often yelled and fought with each other, but the conflicts never became physical. Mother left me alone and I stayed in my room a lot when she was home.

Causal Theory Conclusion: I am an unlovable person.

Biological-Father: I remember him always being sick. He had a serious cancer and stayed in bed most of my childhood. I rarely talked to him but remember him being in a lot of pain. I tried to fix his food but he never ate what I fixed. He never thanked me for trying to help him.

Causal Theory Conclusion: I am not much help when people need it.

Step-Father: He hurt me in many ways. He hated me. He sexually abused me for several years [11 years to 16 years old] and would beat me with a belt whenever I disobeyed. He called me a “whore” and “slut” when I was in high school and started dating.

Causal Theory Conclusion: Men will hurt me if I give them the chance.

Husband: He was an alcoholic, physically abusive and “a loser.” I married him thinking that I would be able to get away from the hell of my family. Anne said: “Lot of good getting married did. I walked right into another nightmare. I divorced my husband two years later.”

Causal Theory Conclusion: I’m afraid of men, they will hurt me.

The interpersonal-emotional THEMES that run through Anne’s SOH causal theory conclusions are as follows:

| • | I’m unlovable. | ||||

| • | I’m ineffectual with a male. | ||||

| • | Males will hurt me. The MALE psychotherapist (called Dr. Howard in this paper) constructed the following Transference Hypothesis (TH) after Session 2: | ||||

| • | If I have a relationship with Dr. Howard, then he will hurt me/reject me in some way. | ||||

Therapist’s note concerning this TH: Patient’s fear of males has been well learned; thus, I predict that Anne expects nothing positive to come out of our relationship.

Next, we describe the process of Transference Hypothesis construction and discuss some of the issues that are associated with TH construction.

Constructing the Transference Hypothesis: Targeting the Salient Transference Domain that Best Fits the Sources of the Interpersonal Fear

The Four Interpersonal Domains

There are four frequently-occurring dyadic interactional domains in psychotherapy that can be used “to anchor” the Transference Hypothesis.

These interactional domains take place between most therapists and patients and include the following (examples of Casual Theory Conclusions appear after each domain):

| • | The Interpersonal Intimacy/Relationship Occurring between Patient and Therapist This domain will also be implicated in the causal theory conclusions where the patient reported that the SOs reactions during moments of intimacy led to felt pain and in some cases, punishment. The content of the TH focuses on the patient’s expectations of a malevolent reaction from the psychotherapist to the dyadic intimacy. Causal Theory Conclusion: “Getting close to a man means that I get hurt.” | ||||

| • | Moments of Verbal Personal Disclosure or Disclosures of Personal Need Where Censure and/or Punishment From SOs was Previously Reported The TH content will make explicit the ways that censure or punishment will probably follow any in-session behavioral event where the patient is honestly forthcoming, verbally discloses highly personal material or, shares a need state with the practitioner. Causal Theory Conclusion: “Letting others know who I am leads to ridicule and rejection.” | ||||

| • | When the Patient Makes Mistakes or Violates Some Rule of Psychotherapy The SOH will have revealed that whenever the patient didn’t perform up to the expectations of the SOs, some type of severe punishment or physical or emotional abuse was administered. The TH anticipates likely mistake events in psychotherapy and makes explicit the expected consequences, e.g. the patient forgets and misses an appointment; the patient does not bring in assigned homework or performs the homework incorrectly; the patient makes in-session mistakes while performing the techniques of CBASP, etc. Causal Theory Conclusion: “I’ve got to be perfect in all things or else I’ll be severely punished or rejected.” | ||||

| • | When the Patient Verbally or Nonverbally Expresses Negative Emotions (e.g., Anger, Frustration, Confusion, Despair Or Hopelessness, Unhappiness, Boredom, Etc.). The patient’s SOH will strongly suggest that negative emotions or any expression of dissatisfaction were not tolerated by the SOs. Thus, the acceptable expressive range in the home was limited to positive affect and smiles. Where this causal theory theme runs through the SOH, the TH makes explicit what is likely to happen in therapy whenever the patient verbally or nonverbally expresses any negative affect to the clinician (e.g., an expected emotional withdrawal or censure on the part of the therapist, etc.). | ||||

Causal Theory Conclusion: “I must always smile and put on a happy face or else face rejection or censure.”

Not surprisingly, these in-session interpersonal events or domains often implicate/parallel the reported sources of pain/injury revealed in the SOH. This point will become clearer as we proceed. Following session two, the clinician selects the one interpersonal domain that is most reflective of the salient theme/motif running through the causal theory conclusions. For example, in the case of Anne, the therapist selected the intimacy/relationship domain in which to anchor the TH by deducing the salient theme/motif from the causal theory conclusions, and selecting the most appropriate TH hot spot, (i.e. one of the four domain-specific interpersonal targets).

The TH must meet two criteria,

| (1) | the therapist’s hot spot choice must reflect the most prominent pain/hurt domain area that the patient experienced with his or her SOs as revealed in the SOH; | ||||

| (2) | and the hot spot selection must specifically pinpoint the one interpersonal context (e.g., when I behave this way, this painful consequence occurs) that most likely exacerbates the person’s generalized interpersonal fear. | ||||

The Transference Hypothesis Must be Stated in a Functional Manner

The TH is always stated in an “if this. . ., then that. . .” sentence. The sentence implies that if the patient engages in one of the domain-specific behaviors, the expected consequence (based on previous learning) will pull some hurtful/painful response from the practitioner. Ethical codes for “professional behavior” dictate against psychotherapists reacting in adverse ways; however, the patient’s emotional system does not always react in ways that adhere to expectations concerning professional behavior. Instead, interpersonal-emotional fears are activated by discrete stimulus cues whenever they occur in common exchanges between clinicians and their patients. These dyadic stimulus fear cues are labeled hot spots and occur when, for example, an intimacy/relationship TH is implicated. The TH helps practitioners recognize these sometimes subtle stimulus cues when they occur in the session. During moments of dyadic shared intimacy, hot spots can take a number of forms. For example, a hot spot is revealed whenever the patient shares an event never-before related, which signals a personal disclosure TH, while a patient forgetting an appointment denotes a lack-of-perfection behavior for one whose TH makes explicit that punishment always follows making a mistake; and lastly, the TH hot spot concerning expressing negative emotion is exposed when the “always smiling patient” becomes overtly frustrated or angry with her therapist.

Common Problems and Issues in TH Construction

Problem 1

Some patients after only two sessions do not provide sufficient information for TH construction. The first author (JPM) has worked with patients whose causal theory conclusions do not result in a clearly defined TH by the end of session two. For example, it took five sessions with one 55-year-old male patient before a relevant TH hypothesis became apparent. The following TH was initially settled on because it expressed a long-standing interpersonal fear in the patient’s life:

If I talk about something I’ve done or accomplished (paint a room;fix the car; mow the lawn, etc.), then I will never be able to do enough to satisfy JPM (the therapist).

Problem 2

The TH is a hypothesis and it can be modified or changed if the practitioner decides that it does not adequately describe the core interpersonal fear. While not a frequent occurrence, this problem does occur and when it does, the TH should be modified to more adequately reflect the patient’s fear. Beginning CBASP practitioners often need assistance in pinpointing the central core fear domain for the TH.

Problem 3

Clinicians must take their gender into account in TH construction, particularly in cases where sexual abuse is reported. A psychotherapist whose gender is the same as the malevolent SO who perpetrated the abuse is likely to evoke a greater fear response than one whose gender differs from the perpetrator.

Problem 4

Lastly, the TH helps practitioners gain better control over their negative emotional responses toward patients (e.g., frustration and hostility). Making the patient’s core interpersonal fears explicit in the TH construction provides the clinician with information with which to understand the patient’s avoidance responses that naturally evoke frustration and felt hostility on the part of practitioners—especially during periods of no change. Understanding the reason for another’s behavior often mitigates knee-jerk adverse reactions that occur when understanding is absent.

The Transference Construct: CBASP & Psychoanalytic Theory

Despite the overlap in terminology, there are some notable distinctions between the generation and utilization of the SOH-informed TH used in CBASP and the use of transference interpretations in psychodynamic psychotherapy (e.g., Høglend, Bøgwald, Amlø, Marble, Ulberg, Sjaastad et el., 2008; Høgland, 2004). Høgland (2004) and Høgland et al. (2008) describe how analytic therapists consider the patient’s historical material and offer a transference interpretation to illuminate the motivation behind some current maladaptive behavior. In one study, Høglend et al. (2008) investigated the efficacy of transference interpretations on a wide variety of psychiatric disorder groups and reported no treatment outcome differences between patients who received transference interpretations and those who did not; however, the authors found that patients who received transference interpretations sustained better relationships on the outside during the four-year period of the study. These articles are important because they demonstrate the use of the transference construct in a widely known psychotherapy model and because they offer us a good yardstick to compare the distinctive use of the construct in CBASP. As noted, several differences exist between CBASP and psychodynamic psychotherapy in transference generation and utilization in treatment. The differences are the following:

| (1) | The Cognitive Behavioral Analysis System of Psychotherapy, which focuses solely on the early-onset chronic patient, differs from psychodynamic theory in its assumption that the core interpersonal fear of the chronic patient derives from a contemporary learning view of fear acquisition (Bouton, 2007). The core fear of the early-onset patient is hypothesized to originate from developmental-interpersonal origins; hence, the CBASP transference construct targets the interpersonal sphere of functioning and not the intra-personal domain of the patient, which is of primary importance in psychodynamic treatment. | ||||

| (2) | Another difference is realized in CBASP’s application of the transference hypothesis, which is designed to teach early-onset patients to discriminate emotionally the psychotherapist from maltreating SOs. The goal of the transference discrimination exercise, Interpersonal Discrimination Exercise or IDE, in CBASP is that of generating felt emotional safety within the therapeutic dyad. We opine that psychoanalytic insight or cognitive enlightenment is simply not sufficient to modify the refractory emotional interpersonal fear that these patients bring to therapy. Patients must learn across repeated trials to make these salubrious emotional discriminations—that is, “my SOs will/have hurt me but my psychotherapist will not.” | ||||

| (3) | The third comparative difference between our approach to the generation and utilization of the transference construct and that of psychodynamic psychotherapy is that CBASP tends to detail its procedures with greater specificity. For example, in the task of interpersonal discrimination, the primary goal of the IDE exercise, has been empirically operationalized (McCullough et al., 2010) so that we can monitor patient IDE learning. We measure the extent to which patients have learned the four-step IDE discrimination task and are able to make these crucial discriminations on their own. More will be said about this empirical issue below. | ||||

| (4) | Finally, it is important to note that the SOH and the TH in CBASP arose from clinical experience and subsequent empirical investigations with one particular type of DSM-IV (APA, 1994) patient, whereas psychodynamic transference methods are applied more universally. | ||||

Using the SOH to Prepare the Way for Teaching One-Person Functioning Patients to Generate Empathy

Anne’s SOH presented previously makes explicit the learned interpersonal fears she brings to treatment. Her fears resulted from maltreatment experiences with SOs and have motivated her to live out a refractory pattern of interpersonal avoidance. Anne is also typical of many early onset chronic patients who are interpersonally closed off from any two-person or circular/reciprocal-deterministic interactions (Kiesler, 1996; Bandura, 1977). The treatment conceptualization question the practitioner must answer is the following: What does Anne have to learn that will “open” the circular interpersonal loop so that her therapist as well as others may inform her behavior? (McCullough et al. 2010).

Over repeated in-session trials, the patient (in this example, Anne) must learn three things: (1) the therapist, Dr. Howard, will not hurt or reject her in any way. In short, Anne must acquire a feeling of felt safety with Dr. Howard as she successfully discriminates him from maltreating SOs; (2) Anne must generalize her felt safety feelings with one or two (or more)

individuals outside of the therapeutic dyad. The in-session gains must be enacted with other social contacts; and (3) that Anne must learn that in reality she is not interpersonally helpless at all. Rather, she can learn to produce the interpersonal outcomes she wants with others. It is hypothesized that the successful acquisition of these learning goals will resolve the chronic depressive disorder (McCullough, et al. 2010).

The Interpersonal Discrimination Exercise

The SOH plays a significant role by helping the patient open the circularity loop first with the psychotherapist and then with others. Anne’s TH is stated once again: If I have a relationship with Dr. Howard, then he will hurt me/reject me in some way. The TH will be activated any time the dyad encounters a relationship issue during the session, signaling that a relational “hot spot” has been encountered (e.g., working together on a task in therapy; talking together about a sensitive personal matter; sharing moments of obvious experienced closeness; etc.). The Interpersonal Discrimination Exercise is then administered (McCullough, 2000, 2006; McCullough & Penberthy, 2011; McCullough, et al., 2010). The IDE administration procedure is shown in Table 2.

The IDE 4-step procedure is based on the Therapist’s Transference Hypothesis:

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Table II. CBASP INTERPERSONAL DISCRIMINATION EXERCISE (IDE) ADMINISTRATION PROCEDURE

The goal of IDE administration is to shape up the patient’s ability to make clear discriminations between the practitioner and her hurtful SOs. The discrimination exercise, administered only once per session, will have the therapist ask the patient to compare and contrast what it was like when she got close to her SOs and what it is like now when she achieves relational closeness with the therapist. In addition, she will also be asked to verbalize the hurt, pain, and fear associated with closeness to the SOs versus the absence of hurt, pain, and fear and the presence of felt safety when closeness is achieved with the therapist. Therapists never achieve adequate discriminations in a few sessions. However, over time and across many in-session encounters where hurt and pain are absent and felt safety is present, patients gradually learn that the therapist is qualitatively different than the SOs who hurt them. During this process, intra-personal functioning and the wall of fear is penetrated, and the “circularity loop” is progressively opened. Being able to perceive the therapist as “different” appears to dissipate the fear. Interpersonal functioning between practitioner and patient now becomes possible, new learning becomes achievable, and patients begin to use language to make themselves understood and to understand the clinician. This characteristic of interpersonal functioning reflects Piaget’s concept of empathy, which denotes a mature, socialized type of language exchange (Piaget, 1923/1926).

Acquisition Learning of Authentic Interpersonal Functioning

It was important that Anne learn what her psychotherapist sought to teach. One thing she learned was to self-administer the 4-step IDE exercise to criterion. First, she mastered pinpointing how her SOs reacted to her in a specific relational-domain context (i.e. relational intimacy was the “hot spot” TH domain). Next, Anne increased her ability to describe the behavior of her clinician as he reacted to her in the same transference-fear domain (i.e. relational intimacy moments). Third, she learned, with progressive clarity, to compare and contrast the interpersonal differences between the SOs THEN and Dr. Howard’s behavior NOW and to discriminate the experienced affect differences (e.g., This was the way I felt THEN, this is the way I feel NOW.). Finally, as Anne came to believe that

she would not be hurt by Dr. Howard, she was increasingly able to identify new interpersonal possibilities open to her.

Assessment of Learning Performance

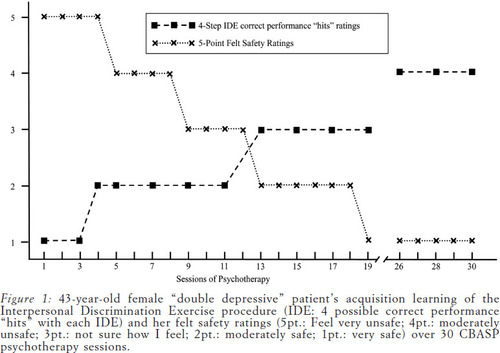

Anne’s therapist rated her in-session IDE performance using the Form for Scoring the Self-Administered Interpersonal Discrimination Exercise ([SAd-IDE] McCullough, et al. 2010). Anne’s IDE acquisition-performance learning curve, reflected in her SAd-IDE scores along with her self-reported felt safety ratings over 30 sessions, are illustrated in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Acquisition-Performance Learning Curve, Reflected in Sad-Ide Scores Along with Self-Reported Felt Safety Ratings Over 30 Sessions

The safety ratings were anchored on a 5-point Likert scale: 1 (feel very safe with the therapist), 2 (feel moderately safe), 3 (not sure how I feel), 4 (feel moderately unsafe) and 5 (feel very unsafe).

Anne reached IDE mastery criterion (McCullough, et al. 2010) during the 27th session, indicating that she self-administered the IDE twice in succession (i.e. during sessions 26th and 27th) with no step errors. Figure 1 also shows the relationship between her IDE performance scores and her self-reported feelings of felt safety with the therapist. The data support a hypothesized dependent relationship between the learning variable (IDE performance scores) and the emotional variable (felt safety scores). Achieving felt-safety was a significant accomplishment for Anne - the process was slow and cumulative.

Conclusions

In summary, patients with early-onset chronic depression who enter treatment unable to function in a two-person manner can learn to function interpersonally and to generate empathy in the therapy dyad (and beyond) if the core fear state is counter-conditioned and replaced with felt safety. The SOH is the procedure used to identify the locus of the interpersonal fears and to provide the content for the TH. Using the TH, the CBASP clinician then begins to teach patients over repeated trials to self-administer the IDE to discriminate between the hurtful behavior of their SOs compared and contrasted to the behavior of the therapist. When patients achieve felt safety within the dyad, learning is enhanced and patients are assisted to counter-condition the avoidance lifestyle replacing it with an interpersonal-approach style of living.

The Limitations of the Soh Proposal

At this point, there are several limitations in this proposal that must be mentioned. There are no data that address the specific contributions that the Interpersonal Discrimination Exercise (IDE) and Situational Analysis (SA) make to the overall effectiveness of CBASP to resolve the patient’s generalized interpersonal avoidance and perceptual disconnection from the environment—the two major treatment goals of CBASP (McCullough et al. 2010).

Stated more specifically, dismantling studies of CBASP are important for future research with the model (McCullough, 2006; McCullough et al., 2010). Formal studies dismantling the specific contributions of the components of CBASP, which seek to compare the SA and IDE separately and in combination, must be undertaken. However, we have replicated intensive design data suggesting that the SOH and IDE exercises increase felt safety of early-onset chronic patients and conversely, decrease their interpersonal fear of the psychotherapist (McCullough, 2005, 2008b; McCullough & Penberthy, 2011; McCullough et al. 2010; as well as the actual case presented in this paper).

Discussing the utility of the SOH when it is employed by other therapeutic models is beyond the scope of the paper. To the authors’ knowledge, the SOH, in the form described herein, has never been used with any other program of treatment. The SOH exercise is taught to all training CBASP clinicians who see patients under the tutelage of CBASP Supervisors. Further information about CBASP training activities may be obtained by going to the CBASP Website: www.cbasp.org.

(1977). Social Learning Theory. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall. Chapter 1: pp. 9-10; Chapter 6: pp. 193-200.Google Scholar

(1978). Beck Depression Inventory-II. Philadelphia, PA: Center for Cognitive Therapy.Google Scholar

(1994). Initial reliability and validity of a new retrospective measure of child abuse and neglect. American Journal of Psychiatry, 151, 1132-1136.Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

(2007). Learning and Behavior: A Contemporary Synthesis. Sunderland, Mass: Sinauer Associates, Inc. Chapter 10, pp. 371-417.Google Scholar

(1969). Interactional Concepts of Personality. Chicago: Aldine.Google Scholar

(1979). Personality and exchange in developing relationships. In R.L. BurgessT/L. Huston (Eds.), Social Exchange in Developing Relationships. New York: Academic Press. pp. 247-269.Crossref, Google Scholar

(1982). Self-fulfilling prophecy, maladaptive behavior, and psychotherapy. In J.C. AnchinD.J. Kiesler (Eds.), Handbook of Interpersonal Psychotherapy. Elmsford, NY: Pergamon. pp. 64-77.Google Scholar

(1991). Attachment organization in maltreated preschoolers. Development and Psychopathology, 3, 397-411.Crossref, Google Scholar

(1998). The development of depression in children and adolescents. American Psychologist,, 53, 221-241.Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

(2000). The construction of autobiographical memories in the self-memory system. Psychological Review, 107, 261-288.Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

(1978). Piaget with Feeling: Cognitive, Social, and Emotional Dimensions. New York: Holt, Rinehart & Winston.Google Scholar

(1976). Toward an interactive description of depression. Psychiatry, 39, 28-40.Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

(1976). Interpersonal Communication. Elmsford, NY: Pergamon.Crossref, Google Scholar

(1991). Psychosocial influences in the etiology, diagnosis, and prognosis of nonorganic failure to thrive. In H.E. FitzgeraldB.M. LesterM.W. Yogman (Eds.), Theory and Research in Behavioral Pediatrics. New York: Plenum. pp. 19-59.Crossref, Google Scholar

(1983). Cognitive Processes and Emotional Disorders. New York: Guilford.Google Scholar

(1992). Cognitive, life stress, and interpersonal approaches to a developmental model of depression. Development and Psychopathology, 4, 189-206.Crossref, Google Scholar

(1995). Interpersonal attachment cognitions and prediction of symptomatic responses in interpersonal stress. Journal of Abnormal Behavior, 104, 436-443.Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

(2004). Analysis of transference in psychoanalytic psychotherapy: A review of empirical research. Canadian Journal of Psychoanalysis, 12, 279-300.Google Scholar

(2008). Transference interpretations in dynamic psychotherapy: Do they really yield sustained effects? American Journal of Psychiatry, 165, 763-771.Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

(2004). Deficit of theory of mind in patients with remitted mood disorder. Journal of Affective Disorders, 82, 403-409.Medline, Google Scholar

(2006). Deficit in theory of mind is a risk for relapse of major depression. Journal of Affective Disorders, 95, 125-127.Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

(1983). Double depression: A two-year follow-up. American Journal of Psychiatry, 140, 680-694.Google Scholar

(2000). A comparison of nefazodone, the Cognitive Behavioral Analysis System of Psychotherapy, and their combination for the treatment of chronic depression. New England Journal of Medicine, 342, 1462-1470.Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

(1996). Contemporary Interpersonal Theory and Research: Personality, Psychopathology, and Psychotherapy. New York: John Wiley.Google Scholar

(1988). Therapeutic Metacommunication: Therapist Impact Disclosure as Feedback in Psychotherapy. Palo Alto, CA: Mind Garden.Google Scholar

(1985). The 1982 Interpersonal Circle: Acts Version. Unpublished manuscript. Richmond: Virginia Commonwealth University.Google Scholar

(1986).The 1982 Interpersonal Circle: An analysis of DSM-III personality disorders. In T. MillonG.L. Klerman (Eds.), Contemporary Perspectives in Psychopathology: Toward the DSM-IV. New York: Guilford.Google Scholar

(1982). The 1982 Interpersonal Circle: A taxonomy for complementarity for human transaction. Psychological Review, 90, 185-214.Crossref, Google Scholar

(1993). The Impact Message Inventory: Form II Octant Scale Version. Palo Alto, CA: Mind Garden.Google Scholar

(1984). Interpersonal Psychotherapy of Depression. New York: Basic Books.Google Scholar

(2009). Cognitive behavioral analysis system of psychotherapy and brief supportive psychotherapy for augmentation of antidepressant nonresponse in chronic depression. Archives of General Psychiatry, 66, 1178-1188.Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

(1955). The theory and measurement methodology of interpersonal communication. Psychiatry, 18, 147-161.Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

(1957). Interpersonal Diaagnosis of Personality. New York: Ronald.Google Scholar

(1954). The prediction of interpersonal behavior in group psychotherapy, Group Psychotherapy, 7, 7-51.Google Scholar

(2008a). Basic assumptions about CBASP emotional mood modification. In J.P McCullough, Jr.R.F. McCullough, CBASP Intensive Training Workbook. Richmond, VA: Virginia Commonwealth University. AppendixGoogle Scholar

(2010). CBASP, the Third Wave and the treatment of chronic depression. Journal of European Psychotherapy, 9, 169-190.Google Scholar

(1984). Cognitive-behavioral analysis system of psychotherapy: An interactional treatment approach for dysthymic disorder. Psychiatry, 47, 234-250.Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

(2005). Cognitive behavioral analysis system of psychotherapy for chronic depression. In J.C. NorcrossM.R. Goldfried, Handbook of Psychotherapy Integration, 2nd ed. New York: Oxford University Press. pp. 281-298.Crossref, Google Scholar

(1975). Cognitive Behavioral Analysis System of Psychotherapy: Rationale and Application. Stages I, II & III. Richmond, VA: Virginia Commonwealth University.Google Scholar

(January, 2009). Form for Scoring the Self-Administered Interpersonal Discrimination Exercise (SAd-IDE). Richmond, VA: Virginia Commonwealth University.Google Scholar

(1980). Helping depressed patients regain control over their lives. Behavioral Medicine, 7, 33-34.Google Scholar

(2008b). The cognitive behavioral analysis system of psychotherapy: A value-added strategy for chronic depression. Psychiatric Times, 25, 26-34.Google Scholar

(2006). Treating Chronic Depression with Disciplined Personal Involvement: CBASP. New York: Springer.Google Scholar

(2000). Treatment for Chronic Depression: CBASP. New York: Guilford.Google Scholar

(2010). A method for conducting intensive psychological studies with early-onset chronically depressed patients. American Journal of Psychotherapy, 64, 317-337.Link, Google Scholar

(2011). CBASP and the treatment of early-onset chronic depression: A case application illustrated and discussed. In Christopher BeeversDavid Springer (Eds.), Treatment of Depression in Adolescents and Adults: Clinician’s Guide to Evidence-Based Practice (pp. 183-220). New York: John Wiley & Sons.Crossref, Google Scholar

(1973). Toward of cognitive social learning reconceptualization of personality. Psychological Review, 80, 252-283.Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

(1992). The Kaspar Hauser Syndrome of “Psychosocial Dwarfism”: Deficient Structural, Intellectual and Social Growth Induced by Child Abuse. Buffalo, NY: Prometheus Books.Google Scholar

(1985). Forensic and family psychiatry in abuse dwarfism: Munchausen’s syndrome by proxy, atonement, and addiction to abuse. Journal of Sex and Marital Therapy, 11, 30-40.Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

(1968). Situational analysis of a therapeutic community milieu. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 73, 49-61.Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

(2003). Differential responses to psychotherapy versus pharmacotherapy in the treatment of patients with chronic forms of major depression and childhood trauma.

(1926). The Language and Thought of the Child. New York: Harcourt, Brace. (Original work published in 1923)Google Scholar

(2011). Cognitive behavioral analysis system of psychotherapy versus interpersonal psychotherapy for early-onset chronic depression: A randomized pilot study. Journal of Affective Disorders, 129, 109-116.Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

(2011). Functional relations of empathy and mentalizing: An f MRI study on the neural basis of cognitive empathy. NeuroImage, 54, 1743-1754Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

(1953a). Conceptions of Modern Psychiatry. New York: Norton.Google Scholar

(1953b). The Interpersonal Theory of Psychiatry. New York: Norton.Google Scholar

(1973). Psychodynamics, behavior therapy and the implacable experimenter: An inquiry into the consistency of personality. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 82, 324-334.Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

(2009). Childhood trauma as a risk factor for chronicity of depression. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, 7, 983-989.Crossref, Google Scholar

(2010). Exploring preoperational features in chronic depression. Journal of Affective Disorders, 124, 262-269.Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

(2006). Autobiographical memory specificity and emotional disorder. Psychological Bulletin, 133, 122-148.Crossref, Google Scholar

(2005). Problem solving deteriorates following mood challenge in formerly depressed patients with a history of suicidal ideation. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 114, 421-431.Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

(2010). Theory of mind deficits in chronically depressed patients. Depression and Anxiety, 27, 821-828.Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar